“Never yet did Olaf

Fear King Svend of Denmark;

This night hand shall hale him

By his forked chin!”

![]()

ON THE ICY MIDNIGHT OF Sunday, 1 January 1899, the silence brooding over Eagle Street, Albany, was disturbed by the sound of smashing glass. Theodore Roosevelt, Governor, had stayed out late after dinner (talking too much, as usual), with the result that forgetful servants had locked him out of the Executive Mansion. Unwilling to disturb his sleeping family, he had no choice but to break into his new home.1

The noise of tinkling shards on the piazza was full of omens, both for himself and Senator Platt. Their brittle alliance had already undergone a severe strain in the matter of appointments.2 How long could it last without cracking? Would Roosevelt, indeed, prove to be the “perfect bull in a china shop” that Platt had feared? Few of the professional politicians staying in the capital that night, in preparation for Monday morning’s Annual Message,3 doubted that the first split would come soon.

Roosevelt himself was determined to proceed with the utmost delicacy. He knew that he could achieve next to nothing in Albany without the Senator’s help—Platt was, as he phrased it, “to all intents and purposes … a majority of the Legislature.”4 Yet if he allowed that majority to control him, as it had Governor Black, he would betray his campaign promises of an independent gubernatorial administration. His duty, as he saw it, “was to combine both idealism and efficiency” by working with Platt for the people.5 This was easier said than done, since the interests of the organization and the community were often at variance; but Roosevelt thought he had a solution. “I made up my mind that the only way I could beat the bosses whenever the need to do so arose (and unless there was such a need I did not wish to try) was … by making my appeal as directly and emphatically as I knew how to the mass of voters themselves.”6 In other words, he looked as always to publicity as a means to wake up the electorate and ensure governmental responsibility. Men like Platt and Odell did not like to operate “in the full glare of public opinion”; their favorite venues were the closed conference room, the private railroad car, the whispery parlors of the Fifth Avenue Hotel. Roosevelt was willing to meet in all these places with them, but he intended to announce every meeting loudly beforehand, and describe it minutely afterward. He would therefore not be asked to do anything that the organization did not wish the public to know about; but whenever Boss Platt had a reasonable request to make, Roosevelt would gladly comply, and see that the organization got credit for it.7

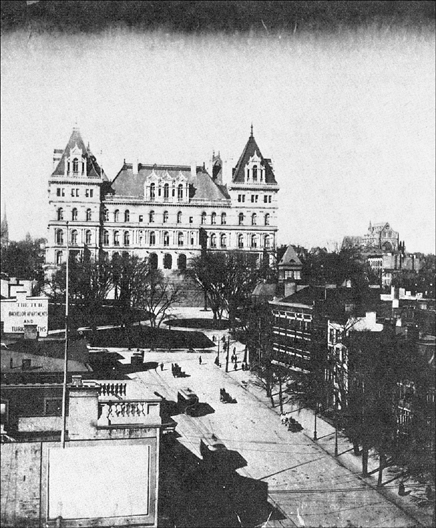

“It was as if the whole $22-million structure had been built just for him.”

The New York State Capitol, Albany, around the turn of the century. (Illustration 27.1)

How well this policy would succeed remained to be seen, as the housebreaking Governor climbed into bed, and got what rest he could before beginning his two-year round of official duties.

![]()

MONDAY, 2 JANUARY, dawned bright, but so cold that when the band arrived to escort Roosevelt to the Capitol, its brass instruments froze into silence, and the procession advanced only to eerie drumbeats. However, the streets were thronged with the biggest crowd of well-wishers ever seen in Albany, and the bunting on every rooftop was brilliant in the sub-zero air. Roosevelt marched along with many grins and waves of his silk topper, surrounded by a shining phalanx of the National Guard, under the command of Adjutant General Avery D. Andrews.8

As he turned the corner of Eagle Street, the white bulk of the Capitol stood out against the sky, as awesomely as it had on that other 2 January when he first walked up the hill as a young Assemblyman, seventeen years before. But then it had been an unfinished pile, with a boarded-up main entrance and mounds of rubble fringing its eastern facade. Now, in place of the rubble, there were lawns and trees, and a new marble stairway, which would have done justice to Cheops, cascading down toward him. Gubernatorial dignity prevented Roosevelt from taking the seventy-seven steps two at a time, as he would invariably do in future. While he mounted with his aides to second-floor level he had leisure to reflect on the improbable series of events that had brought him back to Albany, and the pleasing thought that he would be the first of New York’s thirty-six Governors to occupy the completed Capitol.9 It was as if the whole twenty-two-million-dollar structure had been built just for him.

After briefly seating himself behind a great desk in the Executive Office, where he had once quailed before the wrath of Grover Cleveland, Roosevelt crossed over to the Assembly Chamber. His entrance there aroused none of the old sniggers and inquiries of “Who’s the dude?” Instead, both Houses of the Legislature rose to their feet in welcome, and a band crashed out “Hail to the Chief.” Even more pleasing, perhaps, was the chorus that greeted him when he took the podium to speak:

“What’s the matter with Teddy?

HE’S—ALL—RIGHT!”10

Roosevelt’s First Annual Message was a short, conventional appeal to practical morality and the manly virtues, worded so as not to antagonize any Republican in the room. Insofar as it said anything specific, it recognized the rights of labor, called for civil service and taxation reform, proposed biennial sessions of the Legislature, and expressed concern over Democratic maladministration in New York City. About the only phrase worth remembering was the Governor’s description—or rather self-description—of the ideal public servant: he should be “an independent organization man of the best type.”11 His listeners might have wondered how the two extremes of independence and party loyalty could be combined, but Roosevelt clearly intended to show them. Their applause, therefore, was anticipatory rather than congratulatory, like that of an audience stimulated by the prologue to a suspense drama.

In the corridors afterward the same remark flew back and forth—“What was the boy governor going to do?”12

![]()

ROOSEVELT’S FIRST MAJOR CHALLENGE was to select a new Superintendent of Public Works. This appointment, the most important in his gift, was a particularly sensitive one in view of last year’s “canal steal.”13 Senator Platt had already decided that Francis J. Hendricks of Syracuse was the ideal man, to the extent of actually “naming” him and handing Roosevelt a telegram of acceptance.

Such an arrogant gesture could not go unchallenged. Roosevelt did not hesitate to defend himself.

The man in question was a man I liked … But he came from a city along the line of the Canal, so that I did not think it best that he should be appointed anyhow; and, moreover, what was far more important, it was necessary to have it understood at the outset that the Administration was my Administration and no one else’s but mine. So I told the Senator very politely that I was sorry, but that I could not appoint his man. This produced an explosion, but I declined to lose my temper, merely repeating that I must decline to accept any man chosen for me, and that I must choose the man myself. Although I was very polite, I was also very firm, and Mr. Platt and his friends finally abandoned their position.14

Actually Platt withdrew only temporarily, and looked on, no doubt with malicious amusement, while the Governor tried to find a substitute for Hendricks. One by one the “really first-class men” Roosevelt approached expressed regrets.15 Their reason, unstated but obvious, was that they did not wish to risk the humiliation of nonconfirmation by the Platt-controlled Senate.

The Governor solved the problem by presenting Platt with a list of four suitable candidates and asking his approval of one of them. Colonel John Nelson Partridge was accordingly nominated as Superintendent of Public Works on 13 January 1899. The appointment was widely hailed as “excellent,” and indeed turned out to be so.16 Boss and Governor could congratulate themselves on making a selection that the other approved of. Pride was satisfied, yet there was compromise on both sides.

For the rest of his term Roosevelt would follow this technique of submitting preselected lists to the organization, allowing Senator Platt to make the final choice. With one or two significant exceptions, his appointments were as easy as the Easy Boss could make them.17 Thus Roosevelt demonstrated what he meant by being “an independent organization man of the best type.”

![]()

AS FAR AS THE PRESS was concerned, Governor Roosevelt was a window full of sunshine and fresh air. Twice daily without fail, when he was in Albany, he would summon reporters into his office for fifteen minutes of questions and answers18—mostly the latter, because his loquacity seemed untrammeled by any political scruples. Relaxed as a child, he would perch on the edge of his huge desk, often with a leg tucked under him, and pour forth confidences, anecdotes, jokes, and legislative gossip. When required to make a formal statement, he spoke with deliberate precision, “punctuating” every phrase with his own dentificial sound effects; the performance was rather like that of an Edison cylinder played at slow speed and maximum volume. Relaxing again, he would confess the truth behind the statement, with such gleeful frankness that the reporters felt flattered to be included in his conspiracy. It was understood that none of these gubernatorial indiscretions were for publication, on pain of instant banishment from the Executive Office.19

Unassuming as Roosevelt’s press-relations policy may seem in an age of mass communications, it was unprecedented for a Governor of New York State in 1899. “At that time,” he wrote in his Autobiography, “neither the parties nor the public had any realization that publicity was necessary, or any adequate understanding of the dangers of the ‘invisible empire’ which throve by what was done in secrecy.”20

His particular concern in these press conferences was to make the electorate aware of what he considered the most ominous of “the great fundamental questions looming before us,”21 namely, the unnatural alliance of politics and corporations. It was personified by Thomas C. Platt and Mark Hanna—distinguished, generally admirable individuals, yet afflicted with the curious amorality of big businessmen. Both were corporate executives, both were Senators of the United States. To them, capital was king; the corporation was society in microcosm; government was the oil which made industry throb. Just as tycoons were necessary to control the efficiency of labor, so were bosses required to supervise the writing of laws. If tycoon and boss could be combined in one person, so much the better for the gross national product.

The fact that both Hanna and Platt were personally incorrupt did not reassure Roosevelt at all. Their very asceticism, the impartiality with which they distributed corporate contributions for good or ill, disturbed him. Often as not Platt would finance the campaign of some decent young candidate in a doubtful district, and thus prevent the election of an inferior person. But the decent candidate, once in office, would be tempted to show his gratitude by voting along with other beneficiaries of Platt’s generosity (or rather, the generosity of the corporations behind Platt); and so, inexorably, the machine grew.22

What worried Roosevelt was the inability of ordinary people to see the danger of this proliferation of cogs and cylinders and coins in American life.23 The corrupt power of corporations was increasing at an alarming rate, directly related to the “rush toward industrial monopoly.” In the twenty-five years between the Civil War and 1890, 26 industrial mergers had been announced; in the next seven years there were 156; in the single year 1898 a record $900,000,000 of capital was incorporated; yet in the first two months of 1899—Roosevelt’s initiation period as Governor—that record was already broken.24 What chance did women, children, cowboys, and immigrants have in a world governed by machinery? Clearly, if flesh and blood were to survive, all this cold hardness must be grappled and brought under control.

Roosevelt, of course, had been aware since his days as an Assemblyman of the existence of a “wealthy criminal class” both inside and outside politics, but he had never had the legislative clout to do much damage to it. Not until his election as Governor of New York State could he take up really weighty cudgels, and aim his blows shrewdly against “the combination of business with politics and the judiciary which has done so much to enthrone privilege in the economic world.”25 And not until his third month in office would he feel the real power of the organization to resist change.

In the meantime he busied himself with routine gubernatorial matters, making further appointments, discussing labor legislation with union representatives, reviewing the case of a convicted female murderer,26 approving a minor act or two, and mastering all the administrative details of his job. This was not difficult, thanks to his massive experience of both state and municipal politics. “I am going to make a pretty decent Governor,” he assured Winthrop Chanler, adding defensively, “I do not try to tell you about all my political work, for the details would only bother you. It is absorbingly interesting to me, though it is of course more or less parochial.”27 This last adjective was to become obsessive in his correspondence for 1899—almost as if he were ashamed of enjoying legislation to do with the amount of flax threads in folded linen, or the sale of artificially colored oleomargarine.

“Thus far,” Henry Adams wrote on 22 January, “Teddy seems to sail with fair wind. What we want to know is whether Platt will cut his throat when the time comes, as he has cut the throat of every man whom he has ever put forward.” Roosevelt, meanwhile, protested that Platt was “treating me perfectly squarely … I think everyone realizes that the Governorship is not in commission.”28

He conferred frequently and openly with the old man, traveling down to New York to breakfast with him on Saturday mornings, and lunching or dining as often with organization men like Odell, Quigg, and Root. This, to “silk-stocking” reformers and theEvening Post, was the equivalent of “breaking bread with the devil,”29 but Roosevelt shrugged off their criticism.

The worthy creatures never took the trouble to follow the sequence of facts and events for themselves. If they had done so they would have seen that any series of breakfasts with Platt always meant that I was going to do something that he did not like, and that I was trying, courteously and frankly, to reconcile him to it. My object was to make it as easy as possible for him to come with me … A series of breakfasts was always the prelude to some act of warfare.30

The first clash came in March.

![]()

ON THE EIGHTEENTH DAY of that month, Governor Roosevelt told reporters that he would like to see “the adoption of a system whereby corporations in this State shall be taxed on the public franchises which they control.”31 There were, as it happened, four bills in the legislature to do with franchises—three of them awarding rich concessions to gas, tunnel, and rapid-transit companies in Manhattan, and one proposing a general state tax on all such power and traction privileges, in order to replenish the state treasury.32 It was to the last bill, a measure of Senator John Ford’s then languishing in committee, that Roosevelt seemed to be referring. Although his remark was casual, the committee chairman took the hint, and within three days sent the bill to the House with a favorable report.

Roosevelt, delighted, began to push for its passage at once. Here was a measure designed to siphon off some of the money flowing through the politico-corporate machine and return it to the community in the form of increased values for property owners and, possibly, reduced taxes. The organization might be persuaded to agree—Platt himself had suggested that a tax-reform committee be appointed to send some proposals “to the next Legislature.” But Roosevelt saw no reason to wait until 1900. Hurrying to New York on 24 March, he invited the Easy Boss to breakfast with him at his pied-à-terre on Madison Avenue next morning.33

“I was hardly prepared for the storm of protest and anger which my proposal aroused,” Roosevelt wrote afterward.34 Platt considered the Ford Bill dangerous in the extreme: in its sweeping generalities and “radical” ideas it was “a shot into the heart of the business community” and an “extreme concession to Bryanism.”35 If Roosevelt wished to push such a measure through, the organization would block it. The whole question of tax reform, Platt explained, was too complicated to rush. He repeated his suggestion that a joint legislative committee investigate at leisure, and report in the session of 1900. If Roosevelt agreed to this, Platt promised that some “serious effort would be made to tax franchises.”36

The Governor capitulated, with real or feigned humility, and on 27 March sent a message to the Legislature recommending that Platt’s committee be appointed. He took the opportunity to complain that farmers, market gardeners, tradesmen, and smallholders were bearing a disproportionate burden of taxation in New York State, while franchise-holding syndicates kept every dollar of their profits. “A corporation which derives its power from the State,” he declared, “should pay the State a just percentage of its earnings as a return for the privileges it enjoys.” Then, in a conclusion which struck many commentators as weakly deferential to Platt, he left it to the proposed committee to decide just how franchises should be taxed, and who should do the taxing.37

Since the Ford Bill had specific suggestions on both these points, it was assumed that Roosevelt had given up on the measure. Actually he liked it more and more,38 although he had one reservation: it empowered local county boards to make assessments, rather than the state. This “obnoxious” clause (which played directly into the hands of Tammany Hall) was sufficient to prevent him speaking out publicly in the bill’s favor. But he hinted to various reporters that he would not be sorry to see it pass anyway. On 7 April he risked another Platt “explosion” by telling the editor of the Sun, “I shall sign the bill if it comes to me, gladly.”39

![]()

ON 12 APRIL HE WAS surprised to hear that the Senate had mysteriously passed the Ford Bill by a vote of 33 to 11.40 Whatever Platt’s motive in letting Republican members vote for it (perhaps he was making a gesture to placate tax reformers, while still intending to block the measure in the Assembly), Roosevelt now had an excuse to take a public stand. On 14 April he announced that the bill, however imperfect, was beneficial to the community; the Assembly should send it on to him at once for signing.41 To Platt he guilelessly explained that he had broken silence simply at the request of the Senate Majority Leader, who felt the reputation of the Republican party was at stake. Platt’s response was to employ dilatory tactics. The House Taxation Committee promptly pigeonholed the bill and nothing more was heard of it. Meanwhile a rival measure appeared on the floor and was subject to lengthy debate, obviously for purposes of delay.42

The end of the session, scheduled for 28 April, was fast approaching, and Roosevelt grew impatient. After four months in office he felt sure enough of his strength to challenge Platt directly. He made up his mind “that if I could get a show in the Legislature the bill would pass, because the people had become interested and the representatives would scarcely dare to vote the wrong way.”43 Accordingly he set to work on individual Assemblymen (a task in which he had acquired expertise during his own term as Minority Leader) and used his tame press corps to take daily polls of the increase of likely votes in the House. By noon on 27 April there was a reported majority of twelve in favor of the Ford Bill.44 All that remained now was to persuade Platt’s leaders to bring it out of committee.

As Governor, Roosevelt possessed one formidable weapon which he had hitherto refrained from using: the Special Emergency Message. Under the rules of the Legislature he could use such a ploy to take up any bill out of turn and force it onto the floor.45 At five o’clock, therefore, when pressure in behalf of the Ford Bill had built up to a maximum in the Assembly, Roosevelt dictated his message demanding its immediate passage.

Speaker S. Fred Nixon, who had received direct orders from Platt “not to pass,” simply tore the message up without reading it to the House. He then retired to an anteroom and suffered a nervous collapse.46

![]()

ROOSEVELT HEARD THE NEWS at seven o’clock next morning, the final day of the session. He reacted much as he had when the Mausers were heard at Las Guásimas. Whether he advanced or retreated now, his political life was in danger. Nixon’s rejection of his message, if allowed to go unchallenged, would mean fatal humiliation at the critical moment of his Governorship. What was left of his strength would waste away through the non-legislative months of 1899; when the session of 1900 opened he would be a dead duck, with little hope of renomination by a contemptuous Senator Platt. Meanwhile lobbyists for the big franchise-holders in New York City were warning him that if he sent another message he would “under no circumstances … ever again be nominated for any public office,” as “no corporation would subscribe” to any future Roosevelt campaign.47

Stepping through the barbed wire, the Governor fired off another, more peremptory message:

I learn that the emergency message which I sent last evening to the Assembly on behalf of the Franchise Tax Bill has not been read. I therefore send hereby another message upon the subject. I need not impress upon the Assembly the need of passing this bill at once. It has been passed by an overwhelming vote through the Senate.… It establishes the principle that hereafter corporations holding franchises from the public shall pay their just share of the public burden … It is one of the most important measures (I am tempted to say the most important measure) that has been before the Legislature this year. I cannot too strongly urge its immediate passage.48

This time he entrusted his personal secretary, William J. Youngs, with delivery, and sent an added threat that if the message were not promptly read he would come over and read it himself. Platt’s lieutenants surrendered at once. The Ford Franchise Bill was passed by a landslide vote of 109 to 35, and the Legislature adjourned.49

![]()

LOOKING BACK OVER the session in the first flush of his victory, Roosevelt felt some relief and no little pride in what he had accomplished as Governor.50 There had been, beside this recent spectacular achievement, a good deal of progressive legislation,51 whichmade up in historical significance what it lacked in contemporary drama. “I got an excellent Civil Service law passed,” he boasted, by way of example. This was true enough. The original law which he and Grover Cleveland had engineered in 1883 had been repealed in 1897, for no other reason apparently than to increase Republican spoilsmanship. Cooperating with his old friends at the Civil Service Reform Association, Roosevelt had succeeded in getting a stiff new bill through the Legislature, but only after “herculean labor,” and some spontaneous assistance from Senator Platt. The resultant Act was the most advanced for any state in the nation.52

Roosevelt also congratulated himself, justifiably, on his labor record.53 He had supported, fought for, and signed several bills aimed at improving the working conditions in tenement sweatshops; at strengthening state factory-inspection procedures; at limiting the maximum hours to be worked by employed women and children; and at imposing a stricter eight-hour day law upon the state work force, as an example to other large corporations.54 He consulted widely with union officials—far more than any of his predecessors—and greatly strengthened the state supervisory board to protect industrial workers from exploitation. Fortunately there had been no violent demonstrations to strain his good humor—yet.55

There had been one or two blots on Roosevelt’s record which time would darken, notably his decision in late February to send a woman to the electric chair for the first time in the history of New York State.56 This was in spite of the anguished pleas of humanitarians and warnings that the execution would destroy his Presidential chances.57 The Governor justified his decision by saying that the woman had been fairly convicted of murder, and that in any case sex had nothing to do with the law.58

Roosevelt’s only major inherited problem, the Erie Canal scandal, was for the time being dormant, thanks to his appointment of Superintendent Partridge and courageous selection of two Democrats to reinvestigate. Critics might complain that the delay was unnecessary, given last year’s proof of Republican malfeasance, but few observers doubted that the Governor would prosecute fearlessly if the evidence was upheld.59

“All together I am pretty well satisfied with what I have accomplished,” wrote Roosevelt. “I do not misunderstand in the least what it means—or rather, how little it may mean. New York politics are kaleidoscopic and 18 months hence I may be so much out of kilter with the machine that there may be no possibility of my renomination.…”60

Along with parochial, the adjective kaleidoscopic was increasingly a part of his vocabulary, as he contemplated the rapid shifts of fortune which had marked his recent career. The kaleidoscope continued to shift, ever more rapidly, in the days and months ahead, disclosing sometimes a dazzling perspective to infinity, sometimes dark visions of chaos.

Thus within a month of his boast to Lodge he was confessing to Bamie that he felt “a wee bit depressed”61—a Rooseveltian euphemism for submersion in the Slough of Despond. Having had time to reflect, he realized that his early reservations about the Ford Franchise Tax Bill, now lying on his desk for signature, had been well-founded. The local assessment clause was indeed an alarming problem. In New York City, for instance, it meant that Tammany Hall would have the power to tax all the traction companies—or demand vast bribes for leniency. No wonder his oldest corporate friends, including Chauncey Depew, were incensed at his stand.62 In addition the stock market was down, The New York Times accusing him of opportunism, and, worst of all, Senator Platt had hurled the organization’s ultimate obscenity at him, albeit in a gentlemanly letter, dated 6 May 1899.

“When the subject of your nomination was under consideration, there was one matter that gave me real anxiety,” the Senator wrote. “… I had heard from a good many sources that you were a little loose on the relations of capital and labor, on trusts and combinations, and, indeed, on those numerous questions which have recently arisen in politics affecting the security of earnings and the right of a man to run his own business in his own way, with due respect of course to the Ten Commandments and the Penal Code.” Now came the imprecation: “I understood from a number of business men, and among them many of your own personal friends, that you entertained various altruistic ideas, all very well in their way, but which before they could be put into law needed very profound consideration.”63 Roosevelt knew that in Platt’s vocabulary altruistic meant socialistic or worse.64 “You have just adjourned a Legislature which created a good opinion throughout the State,” the Easy Boss went on loftily. “I congratulate you heartily upon this fact, because I sincerely believe, as everybody else does, that this good impression exists very largely as a result of your personal influence in the legislative chambers. But at the last moment and to my very great surprise, you did a thing which has caused the business community of New York to wonder how far the notions of Populism, as laid down in Kansas and Nebraska, have taken hold upon the Republican party of the State of New York.” The letter began to ramble, and concluded with an almost fatherly appeal to the young Governor’s discretion. “I sincerely believe you will make the mistake of your life if you allow the bill to become a law,” wrote Platt, advising him “with a political experience that runs back nearly half a century”65 not to sign the bill.

Roosevelt deliberated for twenty-four hours before dictating a reply. He wryly thanked the Senator for the “frankness, courtesy, and delicacy” of his letter, not to mention his cooperation during the legislative season. “I am peculiarly sorry that the most serious cause of disagreement should come in this way right at the end of the session.” With tongue firmly in cheek, he assured Platt that he was not “what you term ‘altruistic’ … to any improper degree.” As regards the Ford Bill, “pray do not believe that I have gone off half-cocked in this matter.” Then he launched into a classic statement of his political philosophy.

I appreciate all you say about what Bryanism means, and I also … [am] as strongly opposed to populism in every stage as the greatest representative of corrupt wealth, but … these representatives … have themselves been responsible for a portion of the conditions against which Bryanism is in ignorant, and sometimes wicked revolt. I do not believe it is wise or safe for us as a party to take refuge in mere negation and to say that there are no evils to be corrected. It seems to me that our attitude should be one of correcting the evils and thereby showing, that, whereas the populists, socialists and others really do not correct the evils at all … the Republicans hold the just balance and set our faces as resolutely against improper corporate influence on the one hand as against demagogy and mob rule on the other.66

In hopes of achieving a “just balance” with Senator Platt, the Governor now made a dramatic offer. He was willing to reconvene the Legislature for a special session, in the hope that the Ford Bill’s “obnoxious” assessment clause might be amended. It must be clear to both houses, however, that the essential principle of taxing franchise privileges must stand.67

Organization and corporate lawyers welcomed the idea of an amended bill. They obviously intended to shoot it so full of holes that it would hang limp in any breeze of reform. But Roosevelt had a final ultimatum to make to Platt before sending out his summons to the legislators: “Of course it must be understood … that I will sign the present bill, if the [amended] bill … fails to pass.”68

The Easy Boss remained silent, and on 22 May the Assemblymen and Senators were back at their desks in the Capitol.

![]()

LEAVING NOTHING TO CHANCE, the Governor delivered copies of his ultimatum to the Leader of the Senate and to Chairman Odell, and recruited two of the finest legal consultants in New York State to scrutinize every semicolon that came out of either House. He even arranged for delaying tactics in the event of a recall move, so that he could sign the Ford Bill into law before the pageboys reached his office.69

So short, indeed, was the distance between his pen and the document lying open before him that Platt’s leaders gave up the attempt to write a new bill more favorable to corporations. All they could do was to insert various strengthening clauses into the original bill, exactly as Roosevelt had intended. No amendment was made without his approval, and the revised measure cleared both Houses in three days. The Governor proudly and accurately described it as “the most important law passed in recent times by any State Legislature.” He signed it with a flourish on 27 May, and sat back to enjoy the sweetness of his victory.70

Whether he tasted the fruits to the full is doubtful. For all the praise that poured in from the anti-organization press (“Governor Roosevelt,” declared the Herald, “has given the finest exhibition of civic courage witnessed in this State in many a day”),71 he only knew that he was tired to his bones. “I have had four years of exceedingly hard work without a break, save by changing from one kind of work to another. This summer I shall hope to lie off as much as possible.…”72

![]()

BUT PRESSURE OF speaking engagements up and down the Hudson Valley kept him away from Oyster Bay until the middle of June. Even then he had only a week at home before setting off West to attend the first Rough Riders reunion in Las Vegas, New Mexico. The two-day celebration, “which I would not miss for anything in the world,” was timed to begin on the first anniversary of the Battle of Las Guásimas.73

As he journeyed West he pondered again “the relations of capital and labor … trusts and combinations.”74 Platt might think him “loose” on these subjects, but they preoccupied him more and more as he contemplated America’s entry into the twentieth century. The Ford Bill had been but a step, admittedly a pioneering one, toward resolving the giant inequities of the capitalist system; some future Chief Executive more powerful and visionary than William McKinley must bring about similar legislation on a national scale.

The thought of McKinley made Roosevelt slightly uneasy at present. Ever since taking the oath at Albany he had been receiving demands from the pesky Mrs. Bellamy Storer that he campaign for the promotion to Cardinal of her favorite Archbishop, John Ireland of St. Paul, Minnesota.75 She imagined that as Governor of New York State he could prevail upon the President to prevail upon the Pope. But Roosevelt was aware of various stately squabbles within the Church, and knew that Ireland was persona non grata at the Vatican. He had therefore hedged repeatedly, pleading lack of knowledge, lack of influence, and lack of propriety; but Mrs. Storer would not be put off, and he at last wrote the President a less than enthusiastic plea on her behalf. McKinley’s reply, which had arrived a few days before his departure for the West, was a polite refusal to intervene in the affairs of another State.76

Behind the politeness lurked a hostility that probably went back to the round-robin incident at the end of the war. (The final installment of The Rough Riders, containing Roosevelt’s own account of the affair, along with many hints of Administration mismanagement, was currently on the newsstands.) Roosevelt had long since given up hope of being awarded the Medal of Honor: no War Department board was going to recommend his controversial name to the President.77 But the fact remained that McKinley would probably win a second term in 1900—the election was only eighteen months off—and Roosevelt, if he wished to emerge as a possibility in 1904, must at all costs preserve amiable relations with the White House. On the same day he received McKinley’s rejection of his Storer appeal, he had written querulously to Secretary of State John Hay, “I do not suppose the President ever goes to the seaside. It is not necessary to say how I should enjoy having him at Oyster Bay, if possible.…”78

But as the Governor proceeded west and southwest through Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, and Kansas, he realized that he must offer McKinley something more than sea air as an assurance of loyalty. For the embarrassing fact was that huge crowds were waiting to greet him at every station, “exactly as if I had been a presidential candidate.”79

He found William Allen White was already working for his nomination in Kansas. What the two men said on this subject, during a brief midjourney meeting, is unknown, but White was at least persuaded to avoid setting Roosevelt up as McKinley’s rival in 1900.80 “There is no man in American today whose personality is rooted deeper in the hearts of the people than Theodore Roosevelt,” the little editor wrote, as soon as his friend’s train was over the horizon. “He is more than a presidential possibility in 1904, he is a presidential probability … He is the coming American of the twentieth century.”81

Eastern newspapers mockingly reprinted this and other Roosevelt-for-President editorials, and suggested that McKinley had better look to his skirts at next year’s convention.82

![]()

AFTER THIRTY-SIX raucous hours at Las Vegas, Roosevelt hurried back to New York on 29 June and announced that he was definitely not a presidential candidate. He urged all Americans to vote for the renomination of William McKinley.83 With that he adjourned to Oyster Bay, only to be greeted by a garrulous speaker eulogizing him as “the man in whose hands we hope the destinies of our country will be placed.” At this his gubernatorial dignity began to collapse. He struggled like a small boy to keep his face straight, but grins broke through, and as the crowd burst into applause, he laughed till he shook.84

![]()

“NOW AS TO WHAT YOU say about the Vice-Presidency,” Roosevelt wrote to Henry Cabot Lodge on 1 July.85

Lodge’s first words on this interesting subject are unfortunately lost. But it is clear from their surviving correspondence that he considered a vice-presidential nomination in 1900 to be the best assurance of a presidential nomination in 1904.86 McKinley’s last running mate, Garret A. Hobart, was a nice old boy, but in failing health. Rumor had it he would not seek a second term. The President might prefer to select another nice old boy, like John D. Long; on the other hand, the National Convention might prefer Roosevelt, in which case McKinley would undoubtedly bow to its wishes. As Joe Cannon of Illinois once remarked, “McKinley has his ear so close to the ground it’s always full of grasshoppers.”87

“Curiously enough,” Roosevelt went on in his letter to Lodge, “Edith is against your view and I am inclined to be for it.”88 There were at least two alternative avenues of approach to the White House. One was to continue his admirable career as Governor of New York, and run for reelection in 1900; unfortunately that would only carry him through the year 1902. By 1904 the people who were shouting for him now might well have forgotten about him: “I have never known a hurrah endure for five years.”89 Another choice would be to succeed Russell A. Alger as Secretary of War; it was an open secret that McKinley wanted to get rid of that embarrassing executive. Roosevelt earnestly wanted the Secretaryship (“How I would like to have a hand in remodeling our army!”),90 but McKinley had seen enough of his behavior in the Navy Department to look for somebody less forceful.

All in all, therefore, the Vice-Presidency was his best chance of keeping in the national spotlight until 1904. At least it was “an honorable position.” But, Roosevelt wrote sadly, “I confess I should like a position with more work in it.” There could hardly be an executive position with less.91

Tiredness, intensified by his week of railroading, returned as he finished his letter to Lodge. Word went out that the Governor intended a month’s rest. Reporters, photographers, and glory-seekers were asked to stay away from Sagamore Hill.

“I don’t mean to do one single thing during that month,” said Roosevelt to his sister Corinne, “except write a life of Oliver Cromwell.”92

![]()

ROOSEVELT’S THIRTEENTH BOOK and third biography, which one friend of the family described as a “fine imaginative study of Cromwell’s qualifications for the Governorship of New York,” was completed by 2 August.93 Even allowing for the fact that it was dictated, and that the author spent another month or so revising the manuscript, its speed of composition must be considered something of a record. What was more, Roosevelt did not have the month entirely to himself, as he had planned; McKinley summoned him to the White House for a consultation on the Philippines on 8 July, and he spent three days later in the month at Manhattan Beach trying to restore good relations with Senator Platt.94 Yet somehow he found time to produce sixty-three thousand words of English history, remarkable for clarity and grasp of detail if not for style.95 According to his stenographer, William Loeb, the Governor would appear in his study every morning with a pad of notes and a reference book or two, and proceed to talk “with hardly a pause,” pouring out dates and place-names as copiously as any college professor. The British military attaché Colonel Arthur Lee, who was Roosevelt’s houseguest at this time, remembered him calling in another stenographer and dictating gubernatorial correspondence in between paragraphs of Cromwell, while a barber tried simultaneously to shave him. Yet there was no lack of continuity as the author’s mind switched to and fro. Robert Bridges came out on 12 August to look at the draft typescript, and remembered one chapter “that could have been printed as it stood, with mere mechanical proof-reading corrections.”96

Roosevelt, who shared the ability to double-dictate with Napoleon, did not think his intellect was in any way remarkable. “I have only a second-rate brain,” he said emphatically to Owen Wister, “but I think I have a capacity for action.” When Wister repeated this remark to Lord Bryce many years later, the great scholar was unimpressed. “He didn’t do justice to himself there, you know. He had a brain that could always go straight to the pith of any matter. That is a mental power of the first rank.”97

![]()

OLIVER CROMWELL, HOWEVER, has dated even less well than Thomas Hart Benton and Gouverneur Morris. Unlike those earlier books, it contained no original research. Nor was it short of competitors in the field; even in 1899 it could not compare with the standard lives of the Protector. Reviews were few and apathetic, and the book quickly faded from memory. Yet as a clear, rapid analysis of one leader of men by another, it still has its merits. As with the two previous biographies, Cromwell is most interesting when it draws parallels between author and subject. Roosevelt’s own analysis of it remains the best and most succinct:

I have tried to tell the narrative in its bearings upon the later movements for political and religious freedom in England in 1688 and in America in 1776 and 1860. Have endeavoured to show how the movement had two sides; one mediaeval and one modern, and how it failed, just so far as the former was dominant, but yet laid the foundations for all subsequent movements. I have tried to show Cromwell, not only as one of the great generals of all time, but as a great statesman who on the whole did a marvellous work, and who, where he failed, failed because he lacked the power of self-repression possessed by Washington and Lincoln … The more I have studied Cromwell, the more I have grown to admire him, and yet the more I have felt that his making himself a dictator was unnecessary and destroyed the possibility of making the effects of that particular revolution permanent.98

![]()

NOT SURPRISINGLY, Roosevelt’s flying visit to the capital prompted instant speculation that McKinley, gratified by his recent announcement of support, intended to name him Secretary of War after all.99 The secretaryship was indeed discussed at the White House that night—at such length as to lend credence to the rumors—but Roosevelt, showing remarkable self-control, assumed that if the President wanted his advice on War Department management of the Philippine situation, “he should regard me as wholly disinterested.” He therefore announced as soon as he stepped into McKinley’s office “that I was not a candidate for the position of Secretary of War and could not leave the Governorship of New York now.”100 This protestation seems to have increased McKinley’s respect for Roosevelt as a man, if not as an ambitious politician. On 31 July, Secretary Alger stepped down, and the President named Elihu Root to succeed him. Then Vice-President Hobart, though ailing, let it be known that he would like to remain in office indefinitely, so another of Roosevelt’s avenues for advancement closed off.101

The Governor, setting off for a fall tour of state county fairs, decided to let the kaleidoscope shift for itself for a while.102 In the New Year, once the legislative season was fairly under way, he would gaze through the prisms again and see if any new perspectives had opened up. For the first time in his adult life he felt no desire to hurry. He was, after all, nearly forty-one, with a growing family (Alice was almost as tall as he was now), a decent income, and a job that he loved. “I do not believe,” he told Lodge, “that any other man has ever had as good a time as Governor of New York.”103 Here, within certain geographical and political limits, was the supreme power he had always craved, and the events of last April had shown how well that power became him. Senator Platt, fortunately, had recovered from the Ford Franchise Tax Bill, and was disposed to be “cordial.”104 This augured well for their working partnership through the next session. Roosevelt would live out the nineteenth century in Albany—1900 was not, as so many of his constituents seemed to think, the first year of the twentieth—and try to persuade Platt that he was worth renominating for a second term. “I should be quite willing to barter the certainty of it for all the possibilities of the future.”105

![]()

NIAGARA FALLS. Silver Lake. Chatauqua. Watertown. River-head. Otsego City. Mineola. In fair after fair, all through September, Roosevelt waved, spoke, pumped hands, tasted prize-winning pumpkin pies, and basked in the admiration of the public. Whenever he emerged from his train, whenever he walked past an apple tree full of children, he was greeted with shrieks of “Hello, Teddy, you’re all right!” or, “Three cheers for the next President!” He had a stock response to the latter: “No, no, none of that, Dewey’s not here.”106

This invariably brought laughter and applause. The hero of Manila Bay, now steaming homeward in glory, had indeed emerged as a dark-horse candidate, despite his own protest, “I would rather be an admiral ten times over.” Few professional politicians, Roosevelt included, took the phenomenon seriously.107

The Olympia was scheduled to enter New York Harbor on 28 September, and cruise up the Hudson next morning, to a welcoming thunder of more ammunition than had been expended to destroy the Spanish fleet. On Saturday, 30 September, Admiral Dewey, President McKinley, Senator Hanna, and thirty-five thousand marchers would proceed down Fifth Avenue to Twenty-third Street, where a seventy-foot triumphal arch, modeled after that of Titus in Rome, gleamed white as a symbol of America’s entry into world power. It was to be “the greatest parade since the Civil War,” and Roosevelt, as Governor of the Empire State, would ride at its head in top hat and tails.108

“I am sorry for I happen to have … a particularly nice riding suit, with boots, spurs etc.,” he grumbled to Adjutant General Andrews. But when the great day came, he cut an unusually impressive figure in black and gray. Seated on an enormous charger, with his tall hat flashing, he dwarfed the guests of honor rolling behind him in carriages.109

A small boy named Thomas Beer happened to be standing in Grand Army Plaza as the parade came round the corner of Fifty-ninth Street and began its descent of the avenue. When Beer wrote the concluding pages of The Mauve Decade a quarter of a century later, Roosevelt rode in his impressionistic memory as a figure of strength and promise, great yet uncorrupted by the “disease of greatness,” looming head and shoulders above the fin de siècle pageantry all around him:

A bright dust of confetti, endless snakes of tinted paper began to float from hotels that watched the street … Why, you could see everything from here! … Brass of parading bandsmen and columns wheeled, turning at the red house to the south. Balconies and windows showered down confetti, and roses were blown. The very generous dropped bottles of champagne … The little admiral was a blue and gold blot in a carriage. The President, and the plump senator from Ohio, and all these great were tiny images of black and flesh in the buff shells of carriages in a whirling rain of paper ribbons, flowers, and flakes of the incessant confetti blown everlastingly, twinkling from the high blue of the sky. How they roared! Theodore Roosevelt! The increasing yell came from up the street. A dark horse showed and slowly paced until it turned where now the gilded general stares down the silly city. A blue streamer, infinitely descending from above, curled all around his coat and he shook it from the hat that he kept lifting. Theodore Roosevelt! The figure on its charger passed, and a roar went plunging before him while the bands shocked ears and drunken soldiers struggled out of line, and these dead great, remembered with a grin, went filing by.110

And then, on 21 November 1899, Vice-President Hobart died.