Through the streets of Drontheim

Strode he red and wrathful,

With his stately air.

![]()

ASSEMBLYMAN THEODORE ROOSEVELT arrived in Albany in 17-degree weather, late on the afternoon of Monday, 2 January 1882.1 Alice had gone to Montreal with a party of friends, and would not be joining him for another two weeks. They could look for lodgings then. In the meantime he checked into the Delavan House, a rambling old hotel with whistly radiators, immediately opposite the railroad station. Apart from the fact that it was conveniently located, and boasted one of the few good restaurants in town, the Delavan was honeycombed with seedy private rooms, of the kind that politicians love to fill with smoke; hence it functioned as the unofficial headquarters of both Republicans and Democrats during the legislative season.2

The Assembly was not due to open until the following morning, but Roosevelt had been asked to attend a preliminary caucus of Republicans in the Capitol that evening, for the purpose of nominating their candidate for Speaker.3 He thus had only an hour or two to unpack, change, and prepare to meet his colleagues.

“He was a perfect nuisance in that House, sir!”

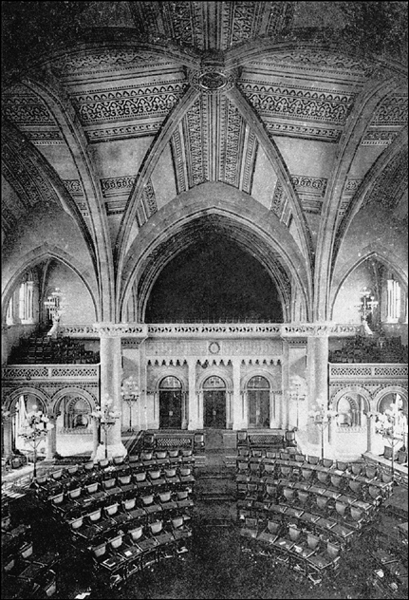

The New York State Assembly Chamber in 1882. (Illustration 6.1)

Dusk came early, as always in Albany, for the little city straggles up the right bank of the Hudson, and is screened off from the plateau above by a two-hundred-foot escarpment of blue clay. But the western sky was clear, and lit by a rising full moon, when Roosevelt emerged from the Delavan House, and began his walk to the Capitol.4

At first he could not see “that building,” as it was locally known, for he had to walk south along the river for a block or two before ascending State Street. Yet already he was moving in its monstrous shadow. Roosevelt had probably read, in his Albany Hand Book, that the new Capitol was, by common consent, “one of the architectural wonders of the nineteenth century.”5 Whether it was a thing of beauty or not was questionable, but there was no doubt, as the Hand Book said, that it was “the grandest legislative building of modern times.” Roosevelt’s first glimpse of the eleven-million-dollar structure, as he rounded the corner of State and Broadway, and focused his pince-nez uptown, was a thrilling one.

Still not quite finished, the stupendous pile of white granite towered out of mounds of construction rubble at the very top of the hill. The Old Capitol, a Greek Revival hall awaiting demolition, stood a little farther down, obscuring some of Roosevelt’s view, yet its dark silhouette merely accentuated the brilliantly lit massiveness looming behind. Jagged against the skyline rose an improbable forest of steeples, turrets, dormers, and gables, all gleaming in the moonlight, for a snowfall the day before had exquisitely etched them out.6 An architect surveying the Capitol’s five stories could successively trace the influence of Romanesque, Italian Renaissance, and French Renaissance styles, with layers of arabesque in between; but to an untutored eye, such as Roosevelt’s, the overall effect was of Imperial Indian majesty.7 Perhaps for the first time the young Assemblyman realized that, as a New York State legislator, he now represented a commonwealth more populous than most of Europe’s kingdoms, rich enough and industrious enough to rank alongside any great power.8

Inspiring as the sight of his destination was, Roosevelt had to concentrate, for the moment, on the tricky business of getting up there without falling down. The steep sidewalks of State Street, when slicked with frozen snow, were notoriously dangerous, and that night blasts of icy air over the escarpment made them doubly so. All sane Assemblymen, of course, were taking horsecars in this weather, but any such indulgence was abhorrent to Roosevelt. Although the wind-chill factor was well below zero, he wore no overcoat.9 A man thus unprotected, yet well stoked with Delavan House coffee, might be able to negotiate two or three blocks of State Street without pain; but he will begin to throb before he is halfway to the top, and Roosevelt was undoubtedly hurting in every extremity by the time he crested the hill and ducked into the warmth of the Capitol lobby.10

As the pain faded to a glow, and his lenses defrosted, he could make out a labyrinth of stone passages and ground-glass doors through which came the busy clacking of typewriting machines. He was standing on the clerical floor. The halls of power, presumably, were somewhere overhead. To his left the Assembly staircase beckoned. One hundred rapid steps elevated him to the second floor, and the famous Golden Corridor opened out before him. Unquestionably the most sumptuous stretch of interior design in the United States, it formed a dwindling perspective of gilded arches and gorgeously painted pillars. High gas globes picked out the filigree on walls of crimson, umber, yellow, and deep blue, and cast pockets of violet shadow into every alcove. Jardinieres of “exotics,” freshly planted to mark the beginning of the legislative season, perfumed the air.11 Roosevelt might well have imagined himself in Moorish Granada, were it not for a very American hubbub coming from a door at the far end of the corridor. Here fifty-two other Republican Assemblymen awaited him in caucus.12

![]()

TO SAY THAT Theodore Roosevelt made a vivid first impression upon his colleagues would hardly be an exaggeration. From the moment that he appeared in their midst, there was a chorus of incredulous and delighted comment. Memories of his entrance that night, transcribed many years later, vary as to time and place, but all share the common image of a young man bursting through a door and pausing for an instant while all eyes were upon him—an actor’s trick that quickly became habitual.13 This gave his audience time to absorb the full brilliancy of his Savile Row clothes and furnishings. The recollections of one John Walsh may be taken as typical:

Suddenly our eyes, and those of everybody on the floor, became glued on a young man who was coming in through the door. His hair was parted in the center, and he had sideburns. He wore a single eye-glass, with a gold chain over his ear. He had on a cutaway coat with one button at the top, and the ends of its tails almost reached the tops of his shoes. He carried a gold-headed cane in one hand, a silk hat in the other, and he walked in the bent-over fashion that was the style with the young men of the day. His trousers were as tight as a tailor could make them, and had a bell-shaped bottom to cover his shoes.

“Who’s the dude?” I asked another member, while the same question was being put in a dozen different parts of the hall.

“That’s Theodore Roosevelt of New York,” he answered.14

Notwithstanding this ready identification, the newcomer quickly became known as “Oscar Wilde,” after the famous fop who, coincidentally, had arrived in America earlier the same day.15 At twenty-three, Roosevelt was the youngest man in the Legislature, recognized not only for his boyishness but for his “elastic movements, voluminous laughter, and wealth of mouth.”16 More bitter epithets were to follow in the months ahead, as he proved himself to be something of an angrily buzzing fly in the Republican ointment: “Young Squirt,” “Weakling,” “Punkin-Lily,” and “Jane-Dandy” were some of the milder ones. “He is just a damn fool,” growled old Tom Alvord, who had been Speaker of the House the day Roosevelt was born.17 Nominated again for Speaker that night, Alvord cynically assessed Republican strength in the House as “sixty and one-half members.”18

Roosevelt had return epithets of his own, and began to record them in a private legislative diary immediately after the 2 January caucus.19 At first, they were merely superficial, revealing him to be as class conscious as his detractors, but as time went by, and the shabbiness of New York State politics (so at odds with the splendors of the Capitol) became clear to him, his pen jabbed the paper with increasing fury.20

“There are some twenty-five Irish Democrats in the House,” the young Knickerbocker wrote. “They are a stupid, sodden, vicious lot, most of them being equally deficient in brains and virtue.”21 Eight Tammany Hall Democrats, representing the machine element, drew his especial contempt, being “totally unable to speak with even an approximation to good grammar; not even one of them can string three intelligible sentences together to save his neck.” Roosevelt’s bête noire (and the feeling was reciprocated) was “a gentleman named MacManus, a huge, fleshy, unutterably coarse and low brute, who was formerly a prize fighter, at present keeps a low drinking and dancing saloon, and is more than suspected of having begun his life as a pickpocket.”22

He was hardly less severe on members of his own party. Ex-Speaker Alvord he instantly dismissed as “a bad old fellow … corrupt.” Another colleague was “smooth, oily, plausible and tricky”; yet another was “entirely unprincipled, with the same idea of Public Life and Civil Service that a vulture has of a dead sheep.” His contempt dwindled reciprocally according to the idealism and independence of the younger members—in other words, those most like himself. Although they could be counted on the fingers of one hand, Roosevelt instinctively sought them out. One in particular caught his eye: “a tall, thin, melancholy country lawyer from Jefferson, thoroughly upright and honest, and a man of some parts.”23

The melancholy youth was named Isaac Hunt. He, too, was serving his first term in the Assembly. But the two freshmen did not get to meet for several days, owing to a strange state of political paralysis in the House. The situation was succinctly summarized in Roosevelt’s diary of 3 January:

The Legislature has assembled in full force; 128 Assemblymen, containing 61 Republicans in their ranks, and 8 Tammany men among the 67 Democrats. Tammany thus holds the balance of power, and as the split between her and the regular Democracy is very bitter, a long deadlock is promised us.24

His forecast proved correct. The very first piece of business before the House—electing a new Speaker—was stalled by the Tammany members, who refused to give their crucial block of votes to either of the major party nominees. Thus each candidate was kept just short of the sixty-four votes required to win.25 Clearly the holdouts hoped that one side or the other would eventually make a deal with them, and that the elected Speaker would reward Tammany with some plum committee jobs. Until then, with nobody in the Chair, there could be no parliamentary procedure, and no legislation.

For the first week in Albany, Roosevelt had nothing to do except trudge daily up State Street and answer the roll call in the Assembly Chamber. Then, there being no further business, he would trudge back to the Delavan House and meditate on the “stupid and monotonous” work of politics.26 Albany was an unattractive place to be bored in: a little old Dutch burg separated from New York by 145 miles of chilly river-valley. Back home, in Manhattan, the social season was at its height, and Fifth Avenue was alive with the sounds of witty conversation and ballroom music. Here it was so quiet at night the only sound in the streets was the clicking of telephone wires. There were, of course, several “disorderly houses” for the convenience of legislators, but such places revolted him.

To vent his surplus energy, he went for long walks around town, but the local air was insalubrious, even to a man with healthy lungs. Depending on the vagaries of the breeze, his nostrils were saluted with the sour effluvia of twenty breweries, choking fumes from the Coal Tar and Dye Chemical Works, and brackish smells from the river. Only on rare occasions did chill, pure Canadian air find its way down from the north, bringing with it the piny scent of lumberyards.27

![]()

ESCAPING TO NEW YORK for his first weekend, Roosevelt put on a cheerful front,28 but it was plain that his first exposure to government had depressed him. With Alice still away (she had gone to Boston to visit her parents), Elliott abroad, and Mittie sweetly uncomprehending, he unburdened himself to Aunt Annie, mother-confessor to all young Roosevelts. The little lady, now married to a banker, James K. Gracie, held court in her brownstone at 26 West Thirty-sixth Street, surrounded by Bibles and fruitcake. It was on her knee that Teedie had learned his ABCs, and early displayed his contempt for arithmetic; now, twenty years later, Assemblyman Roosevelt returned to complain about Albany. “We talked of his book,” she wrote Elliott, “and his political interests. Thee thinks these will only help him in giving him some fame, but neither, he says, will be of practical value in his profession … he says he must begin again at the beginning in the Spring … having gained this intermediate experience.”29

These remarks, and the young man’s earlier avowal, “Don’t think I am going into politics after this year, for I am not,” might be taken with a pinch of salt. Throughout his life, in moments of triumph as well as despair, he would continue to insist he had no future in politics. Relatives and friends soon learned to ignore such protestations, knowing very well that they were insincere, or at best self-delusive. Theodore Roosevelt was addicted to politics from the moment he won his first election until long after he lost his last.

The weekend in New York was sufficiently recuperative for him to bounce back to Albany on Monday, 9 January, with optimistic energy. There was another Republican caucus that night, and although it dealt with the less than fascinating subject of the appointment of Assembly clerks, Roosevelt conscientiously attended. This time he was in even greater sartorial splendor, having dined out somewhere beforehand. Isaac Hunt, the melancholy member from Jefferson County, was standing by the fireplace in the committee room when “in bolted Teddy … as if ejected from a catapult.”30

Deliberately selecting the most prominent position in the room—directly in front of the chairman—Roosevelt sat down and pulled off his ulster. Underneath he was in full evening dress, with gold fob and chain. At the first opportunity he jumped to his feet and addressed the meeting in the affected drawl of Harvard and Fifth Avenue. “We almost shouted with laughter,” Hunt remembered, “to think that the most veritable representative of the New York dude had come to the Chamber.” But as Roosevelt continued to speak, “our attention was drawn upon what he had to say because there was a force in his remarks … it mollified somewhat his unusual appearance.”31

Roosevelt was about to sit down again when he caught sight of Hunt by the fireplace. Instantly he made his way over to him. Hunt, too, as it happened, was overdressed; he was sensitive about his rural background and had invested in a custom-made Prince Albert coat by way of disguise. He might as well have saved his money. “You,” shrilled Roosevelt triumphantly, “are from the country!”32 For the rest of that evening he interrogated Hunt on the minutiae of rural politics. His usual practice, after such an interview, was to discard his victim like a well-sucked orange;33 but something about the young lawyer appealed to him. Hunt, in turn, was charmed. At the end of the caucus the two Assemblymen parted “fast friends.”34 Roosevelt had recruited his first legislative ally.

![]()

FOR THE NEXT FIVE WEEKS there was nothing substantial to be allied against. The deadlock over electing a Speaker seemed unresolvable. Roosevelt continued to vent his impatience with vitriolic diary entries and walks that ranged farther and farther out of Albany. He persuaded his new friend to join him on one of these excursions. The long-legged lawyer came back too tired to speak, and went straight to bed. When Roosevelt suggested another tramp, Hunt begged off. “You will have to get somebody else to walk with you. One dose is sufficient for me.”35

On the second weekend of the session, Roosevelt went to Boston to pick up “the little pink wife,” as he was wont to call her.36 They chose rooms together in a residential hotel on the corner of Eagle and State streets, just across the square from the Capitol. Isaac Hunt had rooms there too, and so saw much of both of them. “She was a very charming woman … tall, willowy-looking. I was very much taken with her.”37

Some older members of the Legislature were less and less taken with Roosevelt. Time, as the deadlock dragged on, hung heavy on their hands, and they began to plot his humiliation. Chief among the bullies was “Big John” MacManus, the ex-prizefighter and Tammany lieutenant whom Roosevelt had so contemptuously characterized in his diary. One day MacManus proposed to toss “that damned dude” in a blanket, for reasons having vaguely to do with the dude’s side-whiskers. Fortunately Roosevelt got advance warning. His feelings, with Alice newly installed in Albany, may well be imagined. Marching straight up to MacManus, who towered over him, he hissed, “I hear you are going to toss me in a blanket. By God! if you try anything like that, I’ll kick you, I’ll bite you, I’ll kick you in the balls, I’ll do anything to you—you’d better leave me alone.” This speech had the desired effect.38

There was a second ugly incident, which proved conclusively that Roosevelt was not to be trifled with. Sporting a cane, doeskin gloves, and the style of short pea jacket popularly known in England as a “bum-freezer,” he went walking along Washington Avenue with Hunt and William O’Neil, another young Republican Assemblyman. They stopped at a saloon for refreshments, and were confronted by the tall, taunting figure of J. J. Costello, a Tammany member. Some insult to do with the pea jacket (legend quotes it as “Won’t Mamma’s boy catch cold?”) caused Roosevelt to flare up. “Teddy knocked him down,” Hunt recalled admiringly, “and he got up and he hit him again, and when he got up he hit him again, and he said, ‘Now you go over there and wash yourself. When you are in the presence of gentlemen, conduct yourself like a gentleman.’ ”

“I’m not going to have an Irishman or anybody else insult me,” Roosevelt said later, still bristling.39

Now that he and Alice were cozily settled in Albany, his impatience over the deadlock dwindled. It occurred to him that, on the whole, the situation was politically profitable. Since only the infighting of Tammany Hall and regular Democrats prevented the election of a Speaker, nobody could blame the Republicans for holding up legislation. The longer the deadlock persisted, he reasoned, the better his party would look, and the more likely its chances of winning a majority in the next election. On 24 January 1882, he had an opportunity to present this view in the Assembly Chamber. A well-meaning colleague was suggesting that the minority compromise with the majority, and so overwhelm the maverick vote of Tammany Hall. Roosevelt leaped up in silent protest, and the Clerk, acting in lieu of a Speaker, recognized him for the first time.

![]()

NO FUTURE PRESIDENT has made his maiden speech in surroundings as inspiring as those framing Theodore Roosevelt that afternoon. Since its completion only three years before, the New York State Assembly Chamber had been acclaimed as the most magnificent legislative hall in the world. Its splendors surpassed even those of the Golden Corridor. “What a great thing to have done in this country!” John Hay had marveled, gazing up at the fabulous vaulted ceiling, a dizzy canopy of vermilion and blue and gold, cleft by ribs of soaring stone. Fifty feet above Roosevelt’s head, as he prepared to speak, hung a three-ton ring of granite, keystone of the largest groined arch ever built. Behind him, on the north wall, loomed a vast allegorical mural by William Morris Hunt, The Flight of Evil Before Good. With pleasing symbolism it depicted the Queen of Night on a chariot of dark clouds, being driven away by the radiance of Dawn.40

Roosevelt’s words were, in contrast to this majestic auditorium, deliberately informal, even prosaic. He did not forget that his audience consisted largely of farmers, liquor sellers, bricklayers, butchers, tobacconists, pawnbrokers, compositors, and carpenters.41His voice was thin and squeaky as he struggled against the chamber’s notorious acoustics, and a general hum of bored conversation.42

It has been said that if the Democrats do not organize the House speedily the Republicans will interfere and perfect the organization. I should very much doubt the expediency of doing this at present.…

A newspaperman was struck by Roosevelt’s “novel way of inflating his lungs.” Between phrases he would open his mouth in a convulsive gasp, dragging the air in by main force.43 Clearly his asthma was troubling him. At times the slight stammer which friends had noticed at Harvard intruded, and his teeth would knock together as the words fought their way out.44 “He spoke as if he had an impediment in his speech,” said Hunt. “He would open his mouth and run out his tongue … but what he said was all right.”45

As things are today in New York there are two branches of Jeffersonian Democrats … Neither of these alone can carry the State against the Republicans … I do not think they can fairly expect us to join with either section. This is purely a struggle between themselves, and it should be allowed to continue as long as they please. We have no interest in helping one section against the other; combined they have the majority and let them make all they can out of it!

There were some scattered bursts of applause, and Roosevelt began to relax.

While in New York I talked with several gentlemen who have large commercial interests at stake, and they do not seem to care whether the deadlock is broken or not. In fact they seem rather relieved! And if we do no business till February 15th, I think the voters of the State will worry along through without it.

Having said his piece, he abruptly sat down, and was inundated with “many hearty congratulations from the older members.”46 Among these, to his intense amusement, were several representatives of Tammany Hall, who apparently thought he had been speaking on their behalf.47 That night the New York Evening Post reported that he had made “a very favorable impression,” an opinion which Roosevelt himself modestly shared.48 He was less flattered with the Sun’s characterization of him next morning as “a blond young man with eyeglasses, English side-whiskers, and a Dundreary drawl.” The paper noted sarcastically that Roosevelt’s “maiden effort as an orator” had been applauded by his political opponents; there was a reference to his “quaint” pronunciation of the words “r-a-w-t-h-e-r r-e-l-i-e-v-e-d.”49

Nevertheless the speech was successful. Roosevelt’s advice was accepted by his party, and the deadlock continued.50

![]()

EARLY IN FEBRUARY the Tammany holdouts finally gave in, and Charles Patterson, Democratic candidate for Speaker, was elected. Announcing his committees on 14 February, Patterson gave Roosevelt a position on Cities. “Just where I wished to be,” the young Republican exulted. He was not charmed with his mostly Democratic companions on the committee, one of whom was “Big John” MacManus. “Altogether the Committee is just about as bad as it could possibly be,” he decided, with the wisdom of his twenty-three years. “Most of the members are positively corrupt, and the others are really singularly incompetent.”51

Roosevelt lost no time in making his presence felt on the floor of the House. Within forty-eight hours of his committee appointment he had introduced four bills, one to purify New York’s water supply, another to purify its election of aldermen, a third to cancel all stocks and bonds in the city’s “sinking fund,” and a fourth to lighten the judicial burden on the Court of Appeals.52 The fact that only one of these—the Aldermanic Bill—ever achieved passage, and in a severely modified form, did not discourage him. He wanted quickly to create the image of a knight in shining armor opposing the “black horse cavalry,” his term for machine politicians.53

As such, he attracted to his banner a tiny group of independent freshman Republicans, like Isaac Hunt and “Billy” O’Neil, who shared his crusading instincts but lacked his flamboyance. The group’s efforts were given wide coverage by George Spinney, legislative correspondent of The New York Times, the first of many thousands of journalists to discover that Roosevelt made marvelous copy. The young reformers supplied their leader with research into suspicious legislation, advised him on correct parliamentary procedure, and attempted to suppress his more embarrassing displays of righteousness. Roosevelt’s ebullience was amusingly recalled forty years later by Hunt and Spinney, in an interview with the worshipful Hermann Hagedorn:

|

HAGEDORN |

He was cool, was he? |

|

HUNT |

No, he was just like a Jack coming out of the box; there wasn’t anything cool about him. He yelled and pounded his desk, and when they attacked him, he would fire back with all the venom imaginary. In those days he had no discretion at all. He was the most indiscreet guy I ever met … Billy O’Neil and I used to sit on his coat-tails. Billy O’Neil would say to him, “What do you want to do that for, you damn fool, you will ruin yourself and everybody else!” |

|

SPINNEY |

You will remember that he was the leader, and he started over the hill and here his army was following him, trying to keep sight of him. |

|

HUNT |

Yes, to keep him from rushing into destruction … |

|

HAGEDORN |

He must have been an entertaining person to have around. |

|

HUNT |

He was a perfect nuisance in that House, sir!54 |

Roosevelt’s behavior on the floor, to say nothing of his high voice and Harvard accent, exasperated the more dignified members of his party. When wishing to obtain the attention of the Chair, he would pipe “Mister Spee-kar! Mister Spee-kar!” and lean so far across his desk as to be in danger of falling over it. Should Patterson affect not to hear, he would march down the aisle and continue yelling “Mister Spee-kar!” for forty minutes, if necessary, until he was recognized.55

By the third week of the session proper—his eighth in Albany—Roosevelt had put on a considerable amount of political weight. Actually this weight was an illusion, caused by the delicate balance of power in the House. But he did not hesitate to throw it around. On 21 February he again rose to protest a suggested deal with the opposite side, confident “that enough Independent Republicans would act with me to insure the defeat of the scheme by ‘bolting’ if necessary.” His senior colleagues were aware of this, and the matter was hastily referred to a party caucus that evening. For the next eight hours Roosevelt was besieged by deputations promising him rich rewards if he would withdraw his objections. He declined.56

At the caucus a machine Republican spoke eloquently on behalf of the deal. It involved an alliance with the Tammany members (breathing vengeance, now, upon the regular Democrats for denying them committee seats) to take away the Speaker’s power of appointment. But this Roosevelt considered to be constitutionally irresponsible and politically demeaning. He wrote afterwards that “as no one seemed disposed to take up the cudgels I responded … we had rather a fiery dialogue.” His objections were upheld by a narrow vote.

Next morning he woke to find himself, if not famous, at least the hero of some liberal newspapers in New York. “Rarely in the history of legislation here,” declared the Herald, “has the moral force of individual honor and political honesty been more forcibly displayed.” Privately, Roosevelt took pride in the fact that he had managed to impose his will on his party, without embarrassing it on the floor of the House. “I hate to bolt if I can help it,” he informed his diary.57

![]()

AS THE TEMPO of legislation picked up, the young reformer became aware of the full extent of corruption in New York State politics. About a third of the entire Legislature was venal, he calculated. He was shocked to see members of the “black horse cavalry” openly trading in the lobbies with corporate backers, and paid particular attention to the bills they were bribed to sponsor—bills worded so ambiguously as to deceive well-meaning legislators. But for every such bill there were at least ten whose corruptive power was all but impossible to monitor in advance.58 These “strike” bills were introduced to restrict, not favor corporations. They seemed to be in the public interest, and redounded greatly to the credit of their sponsors—who, as Roosevelt succinctly put it, “had not the slightest intention of passing them, but who wished to be paid not to pass them.”59 In other words blackmail, not bribery, was the principal form of corruption in the Assembly.

Roosevelt was confronted with a prime example of such legislation early in March. Representatives of the Manhattan Elevated Railroad asked him to sponsor a bill granting their corporation monopolistic control over the construction of terminal facilities in New York City. Since the sums involved in such construction were huge, the lobbyists said they were “well aware that it was the kind of bill that lent itself to blackmail,” and looked to Roosevelt to ensure that it was voted upon honestly. The young Assemblyman scrutinized it carefully. He found that the bill was “an absolute necessity” from the point of view of the city as well as the railroad, and agreed to sponsor it, on condition that “nothing improper” was done on its behalf.60

No sooner had the bill come up before the Cities Committee, of which Roosevelt was then acting chairman, than corrupt members, scenting the spoils of blackmail, combined to delay its progress. Exasperated, he decided to force it through. Since the spoilsmen included Big John MacManus and J. J. Costello, he was aware that something more than parliamentary skill might be required:

There was a broken chair in the room, and I got a leg of it loose and put it down beside me where it was not visible, but where I might get at it in a hurry if necessary. I moved that the bill be reported favorably. This was voted down without debate by the “combine,” some of whom kept a wooden stolidity of look, while others leered at me with sneering insolence. I then moved that it be reported unfavorably, and again the motion was voted down by the same majority and in the same fashion. I then put the bill in my pocket and announced that I would report it anyhow. This almost precipitated a riot, especially when I explained … that I suspected that the men holding up all report of the bill were holding it up for purposes of blackmail. The riot did not come off; partly, I think, because the opportune production of the chair-leg had a sedative effect, and partly owing to wise counsels from one or two of my opponents.61

Chair-legs were of no use in the larger context of the Assembly. Soon, to quote one newspaper, “all the hungry legislators were clamoring for their share of the pie.” Roosevelt found himself wholly unable to push the bill any further. He received an embarrassing second visit from the railroad lobbyists, who suggested that some “older and more experienced” Assemblyman might succeed where he had failed. The bill was accordingly taken out of his hands. Within two weeks it received the unanimous approval of the House, and became law.

Roosevelt was aware that its passage had been bought. There was little he could do but fume against “the supine indifference of the community to legislative wrongdoing.”62

![]()

THIS BITTER EXPERIENCE made him act with caution when his services as a crusader were next called upon. Late in March, Isaac Hunt, who had been investigating the dubious insolvency of a number of New York insurance companies, approached him with what seemed like evidence of judicial corruption at the highest level. Receivers, said Hunt, were milking the companies of hundreds of thousands of dollars in unwarranted fees and expenses. In every case, the order allowing such payments had been issued by State Supreme Court Justice T. R. Westbrook. Further investigation revealed that Westbrook’s son and cousin were employed by one of the receivers, and that at least $15,000 had already been paid to them.

“We ought to pitch into this judge,” said Hunt.63

Roosevelt was noncommittal, saying merely that it was “a serious matter” to undertake the impeachment of a Supreme Court Justice. Yet apparently the name Westbrook stirred something in his retentive memory. On 27 December 1881, The New York Timeshad run a story on the acquisition of the giant Manhattan Elevated Railroad by Jay Gould, accusing him of a campaign to depress its stock before purchase.64 From start to finish, Roosevelt recalled, the transaction had been presided over by this same Judge Westbrook.

A few days later “a thin, anemic-looking, energetic young man” visited the City Desk of The New York Times and subjected the editor there to a barrage of questions about the Gould-Westbrook affair. He asked permission to examine documents in The Times’smorgue, and pored over them for hours. Still not satisfied, Roosevelt took the editor and the documents home to 6 West Fifty-seventh Street, and continued his questioning there until three in the morning.

The more he probed the sequence of events, the more suspicious he became of the cast of characters. About a year before, State Attorney General Hamilton Ward had sued the Manhattan Elevated as an illegal, fraudulent corporation, and then, reversing himself, merely accused it of insolvency. Judge Westbrook, while publicly agreeing with the former suit, had privately ruled in favor of the latter. Holding court in a variety of eccentric locales, including Attorney General Ward’s suite at the Delavan House, he appointed receivers already on Jay Gould’s payroll. Finally, when the stock of the railroad had plummeted by 95 percent, Judge Westbrook suddenly declared the company solvent again, and handed it over to Gould. Most damning of all, in Roosevelt’s eyes, was an unpublished letter the judge had written the financier, containing the remarkable sentence, “I am willing to go to the very verge of judicial discretion to protect your vast interests.”65

Returning to Albany on 28 March, Roosevelt told Hunt that he had decided on a resolution demanding the investigation, not only of Judge Westbrook, but of Attorney General Ward as well. “I’ll offer it tomorrow.”66

![]()

WHEN THE FAMILIAR, piping call of “Mister Spee-kar!” disturbed the peace of the Assembly Chamber the next day, most of Roosevelt’s colleagues assumed that he was rising, as usual, on some exasperating point of order or personal privilege.67 But the first few words of his resolution quickly shocked them into attention:

Whereas, charges have been made from time to time by the public press against the late Attorney-General, Hamilton Ward, and T. R. Westbrook, a Justice of the Supreme Court of this State, on account of their official conduct in relation to suits brought against the Manhattan Railway, and Whereas, these charges have, in the opinion of many persons, never been explained nor fairly refuted … therefore Resolved, That the Judiciary Committee be … empowered and directed to investigate their conduct … and report at the earliest day practicable to this Legislature.68

His words reverberated “like the bursting of a bombshell,” Isaac Hunt remembered forty years later, still awed by Roosevelt’s courage. But the echoes had scarcely died before a member of the “black horse cavalry” rose to announce he would debate the resolution. This was a ploy for time, since the resolution was automatically tabled under a mass of other pending legislation, and would remain there until somebody remembered to resurrect it. In the meantime, Roosevelt might be bullied or bribed into forgetfulness.69

The young Assemblyman did not lack for “friendly warnings” in the days that followed. His own uncle, James A. Roosevelt, took him to lunch and condescendingly remarked that he had done well at Albany so far. It was a good thing to have dabbled in reform, but “now was the time to leave politics and identify … with the right kind of people.” Roosevelt asked if that meant he was to yield to corruptionists. His uncle replied irritably that there would always be an “inner circle” of corporate executives, politicians, lawyers, and judges to “control others and obtain the real rewards.”

Roosevelt never forgot those words. “It was the first glimpse I had of that combination between business and politics which I was in after years so often to oppose.”70

On Wednesday, 5 April, he surprised the Assembly by demanding that debate on the Westbrook Resolution begin immediately. He made his motion less than half an hour before adjournment, at a time when most of the “black horse cavalry” had gone forth in search of Albany ale. “No! No!” shouted old Tom Alvord, as the House voted in favor.71 Having thus won the floor, Roosevelt launched into the first major speech of his career.

![]()

“MR. SPEAKER,” he began, “I have introduced these resolutions fully aware that it was an exceedingly important and serious task I was undertaking.”72 He was ready, nonetheless, to draw up specific charges against “men whose financial dishonesty is a matter of common notoriety.” Just in case anybody wondered whom he meant to accuse of fraud, Roosevelt identified Jay Gould and his associates by name, describing them as “sharks” and “swindlers.” The House, aghast at such blasphemy against the gods of capitalism, fell silent. The only sounds in the chamber were Roosevelt’s straining voice, and the rhythmic smack of right fist into left palm.73

“A suit was brought in May last, I think, by the Attorney-General against the Manhattan Elevated Railroad … declaring the corporation to be illegal …” He went on to recount at length the whole shabby story of Ward’s and Westbrook’s maneuverings in behalf of Jay Gould, and showed how Westbrook, by finally declaring the railroad solvent again, had brought the circle of corruption a full 360 degrees. During his administration of the case, the judge had been so blatant as to hold court in the financier’s office—“once even in a private bedroom.”

The great clock of the Assembly told Roosevelt that fifteen minutes still remained until adjournment. With luck, those few of his opponents who were present would be unable to fill that time with reasonable debate; if so his resolution might be approved by the stunned and silent majority. Sensing that he had the votes already, he wound up with a rather lame attempt to be humble. He was “greatly astonished” that no investigation had been demanded during the three months since the Times exposé, and although “I was aware that it ought to have been done by a man of more experience than myself, but as nobody else chose to demand it I certainly would, in the interest of the Commonwealth of New York … I hope my resolution will prevail.”74

The effect of this speech, according to Isaac Hunt, was “powerful, wonderful.”75 Such direct language, such courageous naming of names, had not been heard in Albany for decades. What was more, Roosevelt’s accusations were obviously based on solid research. If a vote had been held then, according to one correspondent, the resolution would have been approved. But Tom Alvord was already on his feet, displaying remarkable agility for a man of seventy years. With gnarled hands knotted on a cane, and his head swaying from side to side, the ex-Speaker suggested that “the young man from New York” needed time to reflect and reconsider. How many bright legislative careers had been ruined, in this very chamber, by just such irresponsible allegations as these! Why, he himself, when young and foolish, had been tempted to do the same. Fortunately, he had refrained. Public reputations were “too precious” to be lightly assailed … 76

The grandfatherly voice droned on, while the minute hand of the clock crept inexorably toward twelve. At five minutes before the hour Roosevelt asked if the gentleman would “give way for a motion to extend the time.”

Alvord’s reaction was savage. “No,” he shouted, “I will not give way! I want this thing over and to give the members time to consider it!”77 He continued to maunder on; the clock chimed; the gavel dropped; Roosevelt’s resolution returned to the table. Alvord limped out in triumph. “That dude,” he snorted. “The damn fool, he would tread on his own balls just as quick as he would on his neighbor’s.”78

![]()

THAT EVENING THE CAVERNS of the Delavan House hummed with discussion of Roosevelt’s speech, while reporters dashed off the news for front-page headlines in the Thursday papers. “Mr. Roosevelt’s charges,” wrote the Sun correspondent, “were made with a boldness that was almost startling.” George Spinney of The New York Times complimented him on his “most refreshing habit of calling men and things by their right names,” and predicted “a splendid career” for the young reformer. The World correspondent, representing the publishing interests of Jay Gould, was dismissive. “The son of Mr. Theodore Roosevelt ought to have learned, even at this early period of his life, the difference between a call for a legislative committee of investigation and a stump speech.”79

Overnight, both Republican and Democratic machines whirred into silent, efficient action. A secret messenger from Tammany Hall came flying up on the late train, groups of veteran members worked out a strategy to block the “obnoxious resolution,” and Gould’s representatives in Albany began to lobby behind closed doors.80

Next morning, Thursday, Roosevelt called for a vote to lift his resolution from the table. Again, he was outwitted on the floor. The Speaker took advantage of the fact that he had forgotten to say what kind of vote he wanted, and called for members to stand upand be counted. A sea of anonymous heads bobbed quickly up and down. The deputy clerk pretended to count them, recorded a couple of imaginary figures, and the Speaker announced the result: 54 to 50 against.

“By Godfrey!” Roosevelt seethed. “I’ll get them on the record yet!”81

He waited until much later in the day, when the House was drowsing over unimportant business. This time he demanded a name vote. Forced to identify themselves, the members voted 59 to 45 in favor of considering the resolution.82 Roosevelt was still short of the two-thirds majority he needed to launch an investigation of Westbrook and Ward, but time, and public opinion, was on his side. Tomorrow, Good Friday, was the beginning of the Easter recess. During the long weekend, newspapers would continue to discuss his “bombshell” resolution, and by the time the Assembly reconvened on Monday evening, members would have heard from their constituents.

![]()

THE FORCES OF CORRUPTION, meanwhile, were very anxious that Roosevelt’s constituents—the wealthiest and most respectable in the state—should hear something about him. Since the young man was maddeningly immune to coercion and bribery,83 they tried to blackmail him with sex. Walking home to 6 West Fifty-seventh Street one night, he was startled to see a woman slip and fall on the sidewalk in front of him. He summoned a cab, whereupon she tearfully begged him to accompany her home; but he grew suspicious, and refused. As he paid the cabdriver, he took note of the address she gave, and immediately afterward dispatched a police detective to her house. The report came back that there had been “a whole lot of men waiting to spring on him.”84

![]()

THAT EASTER WEEKEND, which saw admiring articles on Roosevelt’s Westbrook Resolution appear in newspapers from Montauk to Buffalo, was sufficient to make his name a household word across New York State. At a time of growing disenchantment with the Republican Party (now widely believed to be controlled by men like Jay Gould), he leaped into the headlines, passionate and incorruptible, a defender of the people against the unholy alliance of politics, big business, and the bench. Particularly adoring were wealthy young liberals, such as his former classmates at Harvard and Columbia. “We hailed him as the dawn of a new era,” wrote Poultney Bigelow, “the man of good family once more in the political arena; the college-bred tribune superior to the temptations which beset meaner men. ‘Teddy,’ as we called him, was our ideal.”85

![]()

BY 12 APRIL, when Roosevelt again moved to lift his resolution from the table, public demand for an investigation of Westbrook and Ward was such that the Assembly voted 104 to 6 in its favor. Prominent among the holdouts were J. J. Costello and old Tom Alvord, the latter predicting darkly that certain “gentlemen who had gone after wool would come back shorn.”86 But Roosevelt, whatever the outcome of the investigation, had already scored a major political triumph. As the Judiciary Committee hearings got under way, his personality visibly expanded. The crudely fermenting energy of his early days in Albany sweetened into a bubbling joie de vivre that vented itself in exuberant slammings of doors, gallopings up stairs, and shouts of laughter audible, George Spinney guessed, at least four miles away.87 His hunger for knowledge on all subjects grew to the point that after every Rooseveltian breakfast, hotel waiters had to clear away piles of ravaged newspapers. A reporter who sat nearby recalled that he read these newspapers “at a speed that would have excited the jealousy of the most rapid exchange editor.” Roosevelt “saw everything, grasped the sense of everything, and formed an opinion on everything which he was eager to maintain at any risk.”88

Like a child, said Isaac Hunt, the young Assemblyman took on new strength and new ideas. “He would leave Albany Friday afternoon, and he would come back Monday night, and you could see changes that had happened to him. Such a superabundance of animal life was hardly ever condensed in a human [being].”89

This new vitality warmed everybody who came in contact with Roosevelt—in particular members of his immediate family. It warmed Alice, lonely in their Albany apartment during the long Assembly sessions; it warmed widowed Mittie and the spinsterish Bamie, coexisting irritably amidst the splendors of 6 West Fifty-seventh Street; it warmed plump, weepy Corinne, as he gave her away in marriage to Douglas Robinson, a man who left her cold;90 it even warmed Elliott, just returned from India, drinking heavily, and still undecided about his future. All huddled close to the glowing youth in their midst, while Theodore himself reveled in “the excitement and perpetual conflict” of politics, the feeling that he was “really being of some use in the world.”91

![]()

WHAT “USE” HE WAS in Albany became a matter of some debate as the months went by. Not for nothing was he known as “the Cyclone Assemblyman,”92 being primarily a destructive force in the House. Indeed, Roosevelt seemed better at scattering the legislation of other men than whipping up any of his own. Although he continued to talk loudly of “moral duty,” his scruples were usually economic. Halfway through the session the Tribune described him as “a watchdog over New York’s treasury.”93 Two months later, after the Aldermanic Bill finally achieved passage, the same newspaper remarked: “This is the only bill that Mr. Roosevelt has succeeded in passing through the Legislature; but as he has killed four score [other] … bills he is probably satisfied with his record.”94

Particularly surprising, in view of Roosevelt’s later renown as the most labor-minded of Presidents, was his attitude to social legislation. It was so harsh that even the loyal Hunt and O’Neil voted against him on occasion. For instance, he vigorously protested a proposal to fix the minimum wage for municipal laborers at $2.00 a day. “Why, Mr. Speaker, this bill will impose an expenditure of thousands of dollars upon the City of New York!”95 He also fought against raising the inadequate salaries of firemen and policemen. When somebody suggested that such people should at least have parity with civil service workers who got more and lived less dangerously, his response was facetious. “Just because we cannot stop all the large leaks, that is no reason why we should open up all the little ones.” Only seven other members agreed with this argument, and the bill was passed overwhelmingly.96

He even opposed a bill which sought to abolish the private manufacture of cigars in immigrant tenements—an abuse which turned slummy apartments into even slummier “factories.” But in this case Roosevelt proved he was not inflexible: a tour of some of the tenements involved revealed such horrors of dirt and overcrowding that he promptly came out in favor of the measure. “As a matter of practical common sense,” he afterward wrote, “I could not conscientiously vote for the continuation of the conditions which I saw.”97

It should be understood that Roosevelt’s attitude toward labor in 1882 was not unusual for a man of his class. Enlightened as he may have been on various outdated aspects of the American dream, he adhered to the classic credo that every citizen is master of his fate.98 His own fate had been an opulent one, in contrast to that of the average tenement-dweller, but he did not think this unfair. After all, his ancestors had worked their way up from a pig-farm in Old Manhattan.

![]()

THE JUDICIARY COMMITTEE did not conclude its investigation of Westbrook and Ward until 30 May, only days before the session of 1882 came to an end. Although the committee’s reports were not due to be made public until noon on 31 May, rumors began to circulate in the small hours of the morning that the majority was prepared to recommend impeachment. Roosevelt and Hunt took a straw poll of their colleagues around 3:00 A.M., which indicated that the Assembly would accept this recommendation; yet even at so late an hour, “mysterious influences” were working against them. There was a frantic burst of last-minute bribery, and three pivotal members of the committee agreed to withdraw their signatures from the majority report, to the tune of $2,500 each.99 Thus in the nine hours preceding the committee’s reports to the House, its majority for impeachment was changed to a majority against. The chairman conceded that Judge Westbrook had occasionally been “indiscreet and unwise,” but said that he was merely guilty of “excessive zeal” in trying to save the Manhattan Elevated from destruction.100

During the reading of this report, Roosevelt was seen writhing with impotent rage.101 At the first opportunity he jumped to his feet and urged the House to vote nay. He kept his temper well in check, speaking slowly and clearly in a trembling voice, but his choice of words was vituperative. “You cannot by your votes clear the Judge … you cannot cleanse the leper. Beware lest you taint yourself with his leprosy!”102

He lost control of himself only once in the ensuing debate, when a speaker referred to him as “the reputed father” of the Westbrook Resolution. “Does the gentleman mean to say,” Roosevelt yelled, “that the resolution is a bastard?”103 His anger was to no avail, and the House accepted the committee’s findings by a vote of 77 to 35.104

Two days later, on 2 June, what The New York Times called “the most corrupt Assembly since the days of Boss Tweed”105 went out of existence. Roosevelt took a rueful farewell of Isaac Hunt, Billy O’Neil, and his other legislative friends, and caught the 7:00 P.M. train to New York, where Alice had already preceded him. Interviewed at Grand Central, he agreed that the session had been a bad one for the Republican party. “There seem to have been no leaders,” he said thoughtfully.106

Early next morning he and Alice joined the other Roosevelts on the blossoming shores of Oyster Bay.

![]()

REVIEWING THE SESSION AT LEISURE that summer (if a schedule including ninety-one games of tennis in a single day can be described as leisurely),107 Roosevelt had little to regret, and much to look forward to. True, Westbrook and Ward had slipped through his fingers at the last moment, but their venality had been exposed, and his political reputation made. Republican newspapers were loud in his praise, and the one national magazine, Harper’s Weekly, had congratulated him on “public service worthy of high commendation.”108 Less than two years out of college, still five months shy of his twenty-fourth birthday, he was already a powerful man, knowing more about New York State politics, in expert opinion, than 90 percent of his fellow Assemblymen. A testimonial dinner in his honor was scheduled at Delmonico’s; his renomination in the fall was certain, and his reelection probable. Already there were rumors that his name might be put up for party leader.109 Should the Republicans win a clear majority in the House, that would automatically put him in line for Speaker.

These were pleasant thoughts for a young man to dwell on in hot, lazy weather, as the sun burned his body hickory-brown, and Alice, a vision of white lace and ribbons, snoozed gracefully in the stern of his rowboat, a volume of Swinburne in her lap.

“All huddled close to the glowing youth in their midst.”

Alice, Corinne, and Bamie Roosevelt, about 1882. (Illustration 6.2)