He was quarrelsome and loud,

And impatient of control.

![]()

ON NEW YEAR’S DAY, 1883, Isaac Hunt stood up at the Republican Assembly caucus in Albany and offered the name of Theodore Roosevelt for Speaker.1 The nomination was approved by acclamation, and Roosevelt could congratulate himself on a political ascent without parallel in American history.2 To use his own phrase, “I rose like a rocket.”3 A year ago he had been “that damn dude”; now, reelected by a record two-to-one majority, he was his party’s choice for the most prestigious office in New York State, other than that of Governor. Yet he was still the youngest man in the Legislature.4 Already, in scattered corners of the country, his name was being dropped by political prophets. In Brooklyn, the columnist William C. Hudson reportedly wrote that he was destined for “the upper regions of politics.” In Iowa, Roosevelt was hailed as “the rising hope and chosen leader of a new generation.” At Cornell University, the eminent Dr. Andrew D. White stopped a history lecture to remark, “Young gentlemen, some of you will enter public life. I call your attention to Theodore Roosevelt, now in our Legislature. He is on the right road to success … If any man of his age was ever pointed straight at the Presidency, that man is Theodore Roosevelt.”5

“If Teddy says it’s all right, it is all right.”

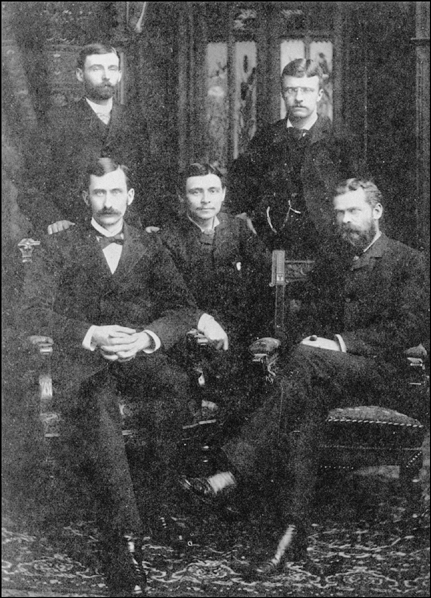

(Clockwise) Theodore Roosevelt, Walter Howe, George Spinney, Isaac Hunt,

and William O’Neil. (Illustration 7.1)

Such predictions were, of course, as farfetched as they were far-flung. Roosevelt dismissed even his nomination for Speaker as “complimentary.”6 He knew he had no chance of winning. The last state election had been a general disaster for his party. Democrats had captured not only the Assembly, but the Senate and Governorship too. This landslide, in the nation’s most powerful legislature, was seen as an omen that the White House, occupied by Republicans since the Civil War, might fall to the opposition in 1884.

The result of the Speakership contest on 2 January emphasized just how much Republican strength in the Assembly had eroded. Voting along party lines, members gave Chapin (D) 84 votes, Roosevelt (R) 41. “I do not see clearly what we can accomplish, even in checking bad legislation,” Roosevelt told Billy O’Neil. Still, he had to admit that the title of party leader was preferable to some of the names he had been called in the last session.7

There was another future President in Albany that January, and a more likely one, in serious opinion, than the foppish young New Yorker. Two years before, Grover Cleveland had been an obscure upstate lawyer, fortyish, unmarried, Democratic, remarkable only for his ability to work thirty-six hours at a stretch without fatigue. Then, in quick succession, he had served eighteen scandal-free months as Mayor of Buffalo, been nominated for Governor, and been elected to that office with the biggest plurality in the history of New York State. The message of the vote was clear: people wanted clean politicians in Albany, irrespective of party. All this made Roosevelt anxious to see “the Big One,” as he was known,8 in the flesh.

There was plenty of flesh to see. Cleveland, at forty-five, was a man of formidable size, weighing well over three hundred pounds.9 Although he moved with surprising grace, his bulk, once wheezily settled on a chair, seemed as unlikely to budge as a sack of cement. Interviewers were reassured by the stillness of the massive head, the steady gaze, the spread of immaculate suiting. The Governor was invariably patient and courteous; his first official announcement had been that his door was open to all comers. Yet the slightest appeal to favor, as opposed to justice, would cause the dark eyes to narrow, and evoke a menacing rumble from somewhere behind the walrus mustache: “I don’t know that I understand you.”10 Should a foolhardy petitioner blunder on, the sack of cement would suddenly heave and sway, and a ponderous fist crash down on the nearest surface, signifying that the interview was over. Often as not, the nearest surface happened to be Cleveland’s arthritic knee. On such occasions everybody in his vicinity scattered.11

Few of the Governor’s visitors could imagine that Cleveland, behind the closed doors of a tavern, was a jovial beer-drinker, a roarer of songs, a teller of hilarious stories. This “other” Cleveland was known only to his friends in Buffalo, and to a quiet-living widow, whose child he had fathered some six years previously.12 Roosevelt would find out about the widow one day, and make political hay of her. In the meantime he liked what he saw of Cleveland, and decided to take advantage of that open door as soon as an opportunity presented itself.

![]()

HE DID NOT EVEN have to make the first move. Early in the session a summons came for him to visit the Governor and discuss a subject of great mutual interest.13 Neither man realized, at the time, just how much effect it would have on their future careers.

The matter Cleveland wished to discuss was Civil Service Reform, an explosive political issue. Simply described, it was a nationwide movement aimed at abolishing the traditional system of political appointments, whereby the party in power distributed public offices in exchange for favors—or cash—received. In place of this “spoils system,” reformers proposed to institute competitive, written examinations for all civil service posts, making merit, rather than corruption, the basis for selection, and ensuring that a good man, once in office, would remain there, independent of the ins and outs of government.

The movement was fiercely opposed by machine politicians, who maintained that they could not govern without the judicious handing out of political plums. President Garfield’s murder by a frustrated office-seeker had caused thousands of idealistic young men, including Theodore Roosevelt, to flock to the reform banner.14 Reform candidates had been conspicuously successful in the elections of 1882. Congress, paying heed, had passed a bill making 10 percent of all federal jobs subject to written examinations. Governor Cleveland now sought to push similar legislation at Albany.15

News that Assemblyman Roosevelt had already introduced a Civil Service Reform Bill in the House caused Cleveland to send for him and his faithful aide Isaac Hunt.16 The Governor expressed strong support for the Roosevelt bill, and asked how it was doing. Hunt, whose responsibility was to guide the paperwork through the Judiciary Committee, reported that it was hopelessly stalled. Machine politicians in the House had no wish to consider such legislation, and had arranged with their colleagues on the committee to let it die of sheer neglect.

For an hour the three men discussed possibilities of getting the bill reported out, favorably or unfavorably, so that an independent, bipartisan vote could be organized on the floor of the House. Roosevelt left the Executive Office encouraged. It was good to know he had won such powerful support—even if Cleveland did belong to the wrong party.17

![]()

ALICE DUTIFULLY CAME UPRIVER at the beginning of January to look for another set of rooms with her husband.18 She seems to have decided—or been persuaded—that she would be better off in New York. With few female friends to visit locally, and, as yet, no child to look after, she indeed had little to detain her. Theodore’s duties as Minority Leader, not to mention four very demanding committee jobs,19 meant that he would be even busier than last year. But every Friday night he would join her in the big city, and stay on through Monday morning. Alice, during her days alone, could enjoy the simple things that gave her pleasure—tennis at Drina Potter’s Club, shopping and gossip with Corinne, tea-parties with Mittie and Bamie, concerts and Bible classes with Aunt Annie.20

Alice had a house of her own to run now. In October 1882, she and Theodore had moved into a brownstone at 55 West Forty-fifth Street. Fanny Smith, a frequent visitor, found it small but pleasant and full of “fun and talk.”21 The preoccupied Assemblyman, on his weekends in town, admitted there was no place like home. Early in the session he wrote in his diary:

Back again in my own lovely little home, with the sweetest and prettiest of all little wives—my own sunny darling. I can imagine nothing more happy in life than an evening spent in my cosy little sitting room, before a bright fire of soft coal, my books all around me, and playing backgammon with my own dainty mistress.22

For all these blissful interludes, he was never reluctant to return to the more Spartan comforts of a bachelor life in Albany. “He stops at the Kenmore,” reported the New York Herald solemnly, “and is said to be very fond of fishballs for breakfast.”23

There is some evidence that Roosevelt, while remaining strictly faithful to his wife, had developed a taste for the “stag” activities enjoyed by Albany legislators, most of whom also left their wives at home in the constituency. “There wasn’t anything viciousabout him,” George Spinney hastened to say, “… he did not visit any bad houses, but anything and everything else.”24

Roosevelt’s best friends in the capital were still Isaac Hunt and Billy O’Neil, plus a new young Republican from Brooklyn, Walter Howe. Together they formed what their leader called “a pleasant quartette.” With George Spinney acting as a non-legislative fifth member, they would occasionally play hookey from the Assembly for a night on the town. By modern standards, these spells of wild abandon were laughably sedate; Roosevelt’s disdain for “low drinking and dancing saloons” was marked even in 1883.25 Since discovering at Harvard that wine made him truculent, he had begun a lifetime policy of near-total abstinence. However an extract from the Hunt/Spinney interviews suggests that a little could go a long way:

|

SPINNEY |

They concluded that I was worthy of a dinner, and we had … a damned good dinner. Of course we talked and we sang. |

|

HAGEDORN |

He did? |

|

SPINNEY |

You never heard Theodore sing? |

|

HAGEDORN |

No, I never did. |

|

HUNT |

Well, he sang that night. |

|

SPINNEY |

On top of the table, too. |

|

HUNT |

With the water bottle, do you remember that?26 |

Here Spinney changes the subject. But he moves on to another anecdote, which indicates that the forces of corruption were still out to besmirch Roosevelt’s public image.

|

SPINNEY |

What was that story about the cockfight? … They put up a job on Roosevelt. Roosevelt liked all sort of athletic sports, and cockfighting was something new to him.… Some of them had arranged for a cockfight in Troy, and I think the place was to be pulled by the police. Well … the place was pulled, but Roosevelt beat it for Albany, and came in puffing and panting into the Delavan House, and telling that he had escaped being pulled in up there … |

|

HUNT |

Next morning some of the fellows had feathers on their coats.27 |

![]()

THERE WERE TIMES, during the early months of the session, when Roosevelt seemed not unlike a fighting cock himself. His raucous, repetitive calls of “Mister Spee-kar!,” his straining neck, wobbly spectacle ribbons, and rooster-red face were combined with increasing aggressiveness and a fondness for murderous, pecking adjectives. If his opponents were tough, and big enough to fight back, these adjectives could be effective and amusing—as when he denounced Jay Gould’s newspaper the World as “a local, stockjobbing sheet of limited circulation and versatile mendacity, owned by the arch thief of Wall Street and edited by a rancorous kleptomaniac with a penchant for trousers.”28 (The paper often lampooned Roosevelt’s fashionable attire.) But at other times, and on a more personal level, his words left wounds. As party leader in the Assembly, he admitted to no patience with “that large class of men whose intentions are excellent, but whose intellects are foggy,” and attacked them openly on the floor. An Irish Democrat was dismissed as “the highly improbable, perfectly futile, altogether unnecessary, and totally impossible statesman from Ulster.”29 One seventy-year-old Assemblyman, hurt beyond endurance by Roosevelt’s incessant vituperation, took the floor, on a point of personal privilege, to defend himself. His refutations were so eloquent that Roosevelt was moved to make a tearful apology. “Mr. Brooks, I surrender. I beg your pardon.”30

Many of the young man’s early gaucheries can be ascribed to that most powerful of political temptations, the desire to see one’s name on the front page of tomorrow’s newspaper. Ever since the Westbrook affair, reporters had clustered flatteringly around him. They had discovered that the noticeable word ROOSEVELT, besprinkled over a column of otherwise dull copy, was a guarantee of readership. And so, hypnotized by the scratching of shorthand pencils, he talked on. He was unaware that some of his remarks were causing experienced politicians to shake their heads. “There is a great sense in a lot that he says,” Grover Cleveland allowed, “but there is such a cocksuredness about him that he stirs up doubt in me all the time.”31

It was clear that Roosevelt was enjoying himself, and equally clear that he would soon come a cropper. He showed a dangerous tendency to see even the most complicated issues simply in terms of good and evil. As a result, his speeches often sounded insufferably pious. “There is an increasing suspicion,” wrote one Albany correspondent, “that Mr. Roosevelt keeps a pulpit concealed on his person.”32 Heretics noted with amusement that, in his theology, God always resided with the Republicans, while the Devil was a Democrat. “The difference between your party and ours,” he angrily yelled across the floor one day, “is that your bad men throw out your good ones, while with us the good throw out the bad!” Nor was this enough: “There is good and bad in each party, but while the bad largely predominates in yours, it is the good which predominates in ours!” Such oversimplifications always made him seem rather ridiculous. “When Mr. Roosevelt had finished his affecting oration,” the New York Observer reported, “the House was in tears—of uncontrollable laughter.”33

![]()

IN FAIRNESS TO ROOSEVELT, it must be admitted that he was under considerable strain when he made the above-quoted remark, on 9 March 1883. A few days before he had reversed his public position on a bill of major importance, and had unleashed an avalanche of bitter personal criticism. For the first time in his career, both friends and enemies seemed genuinely outraged. Even the faithful Billy O’Neil (whose philosophy had always been “If Teddy says it’s all right, it is all right”) split with him on this issue.34

The bill was one which proposed to reduce the Manhattan Elevated Railroad fare from ten cents to five. Its grounds were that Jay Gould, owner of the corporation, earned far too much profit—profit which he unscrupulously concealed for the purposes of tax evasion. Any such fare-reducing measure was bound to be enormously popular with the masses, and Roosevelt had given “the Five-Cent Bill” his full support, right from the beginning of the session. If a fellow member had not introduced it, he told the press, he would have done so himself, “for the measure is one deserving of support of every legislator in this city.” Both the Assembly and Senate had concurred, and passed the bill by overwhelming majorities. By 1 March it was ready for Grover Cleveland’s signature.35

But the bill’s backers, Roosevelt included, reckoned without the deep and laborious scrutiny that the Governor gave to every measure, no matter how public-spirited it might seem on the surface. Lights in the Executive Office, which rarely went off before midnight, burned into the small hours of 2 March as Cleveland agonized over the Five-Cent Bill. He found it unconstitutional. The state had entered into a contract with Gould allowing the elevated railroad to charge ten cents a ride, and it was honor bound to that contract. If the financier fattened on it, that was the state’s fault. Aware that he was risking his political future, the Governor wrote a firm veto. He went to bed muttering, “Grover Cleveland, you’ve done the business for yourself tonight.”36

Next day, much to his surprise, he discovered that he was an instant hero. Both press and public praised him for an inspiring act of courage. His veto message declaring that “the State must not only be strictly just, but scrupulously fair” shocked the Assembly into applause.37 Roosevelt was the first to rise in support of the veto. Full of admiration for Cleveland, he spoke with unusual humility:

I have to say with shame that when I voted for this bill I did not act as I think I ought to have acted … I have to confess that I weakly yielded, partly to a vindictive spirit toward the infernal thieves who have the Elevated Railroad in charge, and partly in answer to the popular voice of New York.

For the managers of the Elevated Railroad I have as little feeling as any man here, and I would willingly pass a bill of attainder on Jay Gould and all of his associates, if it were possible. They have done all possible harm to this community, with their hired newspapers, with their corruption of the judiciary and of this House. Nevertheless … I question whether the bill is constitutional … it is not a question of doing right to them. They are common thieves … they belong to that most dangerous of all classes, the wealthy criminal class.38

That acid phrase, “the wealthy criminal class,” etched itself into the public consciousness.39 Long after other details of the young Assemblyman’s career were forgotten, it survived as an early example of his gift for political invective. For the moment, its sting was such that Roosevelt’s audience took little notice of his concluding peroration, in which the future President spoke loud and clear.

We have heard a great deal about the people demanding the passage of this bill. Now anything the people demand that is right it is most clearly and most emphatically the duty of this Legislature to do; but we should never yield to what they demand if it is wrong … I would rather go out of politics having the feeling that I had done what was right than stay in with the approval of all men, knowing in my heart that I have acted as I ought not to.

Roosevelt’s speech, undoubtedly the best he ever made at Albany, earned him widespread scorn. He was denounced by both hostile and friendly newspapers as a “weakling,” “hoodlum,” and “bogus reformer.”40 Very few commentators realized that, in openly admitting he was wrong, Roosevelt was in fact a braver man than the Governor. He need not have said anything at all: any fool in the Assembly that morning could see that the majority would accept Cleveland’s veto. Roosevelt, as Minority Leader, merely had to record a token vote against it, and his political honor would be intact. Both Hunt and O’Neil urged him to do this, but he was more concerned with personal honor. So it was that on 7 March 1883 he found himself voting, along with Democrats and the hated members of Tammany Hall, to accept the Governor’s veto, while members of his “quartette” voted the other way.41

On top of this humiliation came the House’s decision, on 8 March, to unseat a Roosevelt associate named Sprague, on the suspicion of election irregularities. Roosevelt himself was a member of the Committee of Privileges and Elections, which had recommended that Sprague be allowed to stay. The House rejected its report. At once Roosevelt’s self-control cracked, and he furiously announced that he was resigning from the committee. As for the Democratic majority, he waxed Biblical in his wrath. “No good thing will come out of Nazareth … Exactly as ten men could have saved the ‘cities of the plains,’ so these twelve men [who had voted for Sprague] will not save the Sodom and Gomorrah of the Democracy. The small leaven of righteousness that is within it will not be able to leaven the whole sodden lump …”42

He went on, for almost fifteen minutes. This was the speech which reportedly left his audience “in tears—of uncontrollable laughter.” The House refused to accept Roosevelt’s resignation, and, ignoring his strident protests, went about its business.43

![]()

IF ROOSEVELT HAD BEEN a hero to the press before, he now found himself its favorite clown. Democratic newspapers joyfully quoted his “silly and scandalous gabble” and intimated that he, too, was a member of “the wealthy criminal class.” He was dubbed “The Chief of the Dudes,” and satirized as a tight-trousered snob, given to sucking the knob of an ivory cane. Some of these editorials were undeniably comic.44 What he read in the World, however, was not so funny. Jay Gould’s editors cruelly invoked a precious memory: “The friends who have so long deplored the untimely death of Theodore Roosevelt [Senior] cannot but be thankful that he has been spared the pain of a spectacle which would have wounded to the quick his gracious and honorable nature.” A short quotation followed:

His sons grow up that bear his name,

Some grow to honor, some to shame—

But he is chill to praise or blame.45

Grover Cleveland came to the rescue. Glowing with the praise that had been heaped on him since the veto of the Five-Cent Bill, the Governor could not help being touched by the fate of his innocent Republican ally. Another summons came for Roosevelt to visit the Executive Office and discuss pending Civil Service legislation.46

He reported that his Civil Service Bill, long stuck in the Judiciary Committee, was back on the Assembly table at last. (Isaac Hunt had sneaked it out of the committee when the chairman was absent.) Cleveland made him a flattering offer and promise. If the “Roosevelt Republicans” would move the bill off the table, “Cleveland Democrats” would ensure its passage.47

Both men were aware that much larger issues were at stake than the mere movement of a bill they happened to care for. Cleveland’s victory as Governor had been achieved with the help of Tammany Hall, and for the first few months of his administration he had allowed that corrupt institution to think that he was beholden to it.48 Yet now he was proposing to force through the Assembly a bill that was anathema to machine politicians, and, what was more, enlisting the aid of Tammany’s bitterest enemy in the House. In other words, the Governor was about to destroy the unity he had so recently created in the Democratic party. Roosevelt cannot but have been fascinated by his motives. Did Cleveland, too, feel the groundswell of reform sentiment building up across the land?

![]()

ROOSEVELT PROMPTLY MOVED for passage of his Civil Service Reform Bill, and made the principal speech in its behalf on 9 April. His humilitation of the previous month had reminded him of the value of brevity, but he spoke as forcefully as ever: “My object in pushing this measure is … to take out of politics the vast band of hired mercenaries whose very existence depends on their success, and who can almost always in the end overcome the efforts of them whose only care is to secure a pure and honest government.”49

The immediate reaction to his speech was predictable. A representative of the “black horse cavalry” stood up to say that Roosevelt had “prated a good deal of nonsense.” But Governor Cleveland’s promise held good: only three Democrats voiced any objection to the bill, to the great mystification of Tammany Hall. However they did so at such length that no action was taken that evening.50 Tammany mustered its forces somewhat in the days that followed, and was able to delay any progress for several weeks, but the Roosevelt/Cleveland coalition of independents finally triumphed. The Civil Service Reform Bill was sent to the Senate, which passed it on 4 May, the last day of the session.51

“And do you know,” said Isaac Hunt long afterward, “that bill had much to do with the election of Grover Cleveland. When he came to run for President, the non-partisan liberal-minded citizens, who were not affiliated very strongly with either party, voted for Cleveland.” But, Hunt added, “Mr. Roosevelt was as much responsible for that law as any human being.”52

![]()

ROOSEVELT’S OWN RECOLLECTION of his political performance as Minority Leader was that, having risen like a rocket, “I came an awful cropper, and had to pick myself up after learning by bitter experience the lesson that I was not all-important.”53 On another occasion he remarked, “My isolated peak had become a valley; every bit of influence I had was gone. The things I wanted to do I was powerless to accomplish.”54

The facts do not entirely support this negative view. Although he certainly “came an awful cropper” two-thirds of the way through the session, his legislative record was better than it had been in 1882. His activities on behalf of Civil Service Reform have already been noted. In addition, he helped resurrect the lost Cigar Bill, pushed it through the Assembly, and persuaded a doubtful Governor to sign it into law.55 During the customary flow of legislation just before adjournment, Roosevelt and his “quartette” were successful in killing many corrupt measures.

He did suffer many defeats during the session, but they were on the whole honorable ones, proving that he was a man who fought for his principles. The fact that the House majority was heavily Irish did not prevent him attacking a bill to appropriate money to a Catholic protectory, on the grounds that church and state must be separate. He fought reform of the New York City Charter, saying that the suggested changes were more corrupt than the status quo; he attempted to raise public-house license fees “to regulate the growing evil in the sale of intoxicating liquors.” He objected to bills designed to end the unfair competition of prison and free labor, which he believed preferable to having criminals live in idleness; he even introduced a bill “to provide for the infliction of corporal punishment upon [certain] male persons” at a public whipping-post. (One commentator mischievously predicted that, if this bill became law, Roosevelt would wish to restore “the thumbscrew and rack.”)56

As for losing “every bit” of his influence, he actually retained all of it, in the opinion of The New York Times. “The rugged independence of Assemblyman Theodore Roosevelt and his disposition to deal with all public measures in a liberal spirit have given him a controlling force on the floor superior to that of any member of his party,” the paper reported. “Whatever boldness the minority has exhibited in the Assembly is due to his influence, and whatever weakness and cowardice it has displayed is attributable to its unwillingness to follow where he led.”57 Other reform-minded periodicals complimented him, if not quite so fulsomely.58

The most interesting appraisal of Roosevelt in the session of 1883 remained unspoken for a quarter of a century. “It was clear to me, even thus early,” Grover Cleveland remembered, “that he was looking to a public career, that he was studying political conditions with a care that I have never known any man to show, and that he was firmly convinced that he would some day reach prominence.”59

![]()

ON 28 MAY 1883, three weeks after the Legislature adjourned, the Honorable Theodore Roosevelt was a guest of honor at a bibulous party at Clark’s Tavern, New York City. The occasion was a meeting of the Free Trade Club; and although Roosevelt spoke seriously on “The Tariff in Politics,” the evening quickly became social. Bumpers of red and white wine and “sparkling amber” flowed freely, as the mostly young and fashionable audience toasted vague chimeras of future reform.60 Free Trade was in those days a doctrine almost as controversial as Civil Service Reform, and Roosevelt admitted that he was risking “political death” by espousing it.61 Although he indeed came to regret his speech, he never regretted going to Clark’s that hot spring night, for a chance meeting occurred which directly influenced the future course of his life.

There was at the party a certain Commander H. H. Gorringe, who happened to share Roosevelt’s dreams of a more powerful American Navy.62 It was natural that this retired officer should wish to meet the young author of The Naval War of 1812, and equally natural that, having discussed nautical matters at length, the two men should turn to another subject of mutual interest—buffalo hunting.

The recent return from India of Elliott Roosevelt, laden down with trophies of Oriental big game, had aroused a great longing in his brother to do something similarly romantic.63 The papers were full of newspaper articles about hunting ranches in the Far West, where wealthy dudes from New York were invited to come in search of buffalo. By a strange coincidence, Commander Gorringe had just been West, and was in the process of opening a hunting ranch there himself. When Roosevelt wistfully remarked that he would like to shoot a buffalo “while there were still buffalo left to shoot,” Gorringe, scenting business, suggested a trip to the Badlands of Dakota Territory.

The Commander said that he had bought an abandoned army cantonment there, at a railroad depot on the banks of the Little Missouri. Although the cantonment was not yet ready to receive paying guests, there was a hotel—of sorts—at the depot, plus a few stores and a saloon where hunting guides might be found and hired, if sufficiently sober. The countryside round about teemed with buffalo, not to mention elk, mountain sheep, deer, antelope, beaver, and even the occasional bear. Gorringe added that he was returning to Little Missouri in the fall. Perhaps Roosevelt would like to come along.64

![]()

ROOSEVELT WAS QUICK to accept. But he had more pressing matters to consider that spring. Alice had just become pregnant. The news stimulated his old ambition to build Leeholm, the hilltop manor at Oyster Bay. Since his initial purchase of land there, a few weeks after their wedding, he had been too busy with politics to think much about the future; but now the responsibilities of parenthood crowded upon him. He began to plan a house that befitted his stature as a man of wealth, public influence, and proven fertility.65

Since he and Alice would live out their days at Leeholm, surrounded of course by numerous children, his first instincts were toward solidity and size. What the manor would look like was of less consequence than what it would feel like to live in. Apart from Roosevelt’s natural penchant for massive walls, heavy oak paneling, and stuffed segments of large animals, he was not, at this stage, interested in decorative details. But he did have “perfectly definite views” as to the general layout of his home.

I wished a big piazza, very broad at the n.w. corner where we could sit in rocking chairs and look at the sunset; a library with a shallow bay window opening south, the parlor or drawing-room occupying all the western end of the lower floor; as broad a hall as our space would permit; big fireplaces for logs; on the top floor the gun room occupying the western end so that north and west it look[ed] over the Sound and Bay.66

Questions of health—his own, rather more than Alice’s—prevented him from making any more definite architectural plans. The nervous strains of the past winter, aggravated by the excitement of becoming a prospective father, brought about a return of asthma and cholera morbus. This time he became so ill that, looking back on the summer of 1883, he described the whole period as “a nightmare.”67 At the beginning of July the family doctor sentenced him to “that quintessence of abomination, a large summer hotel at a watering-place for underbred and overdressed girls”—Richfield Springs, in the Catskill Mountains.68 Characteristically, Roosevelt chose to drive there with Alice in the family buggy. Settling down amid “a select collection of assorted cripples and consumptives,” he submitted patiently to a variety of cures, and relieved his embarrassment in a humorous letter to Corinne.69

The drive up was very pleasant—in spots. In spots it wasn’t … as we left civilization, Alice mildly but firmly refused to touch the decidedly primitive food of the aborigines, and led a starvling [sic] existence on crackers which I toasted for her in the greasy kitchens of the grimy inns. But, on the other hand, the scenery was superb; I have never seen grander views than among the Catskills, or a more lovely country than that we went through afterwards; the horse, in spite of his heaves, throve wonderfully, and nearly ate his head off; and Alice, who reached Cooperstown very limp indeed, displayed her usual powers of forgetting past woe, and in two hours time, after having eaten until she looked like a little pink boa constrictor, was completely herself again. By the way, having listened with round eyed interest to one man advising me to “wet the feed and hay” of Light-foot, she paralyzed the ostler by a direction “to wet his feet and hair” for the same benevolent object. Personally, I enjoyed the trip immensely, in spite of the mishaps to both spouse and steed, and came into Richfield Springs feeling superbly. But under the direction of the heavy-jowled idiot of a medical man to whose tender mercies Doctor Polk has intrusted me, I am rapidly relapsing. I don’t so much mind drinking the stuff—you can get an idea of the taste by steeping a box of sulphur matches in dish water and drinking the delectable compound tepid, from an old kerosene oil can—and at first the boiling baths were rather pleasant; but, for the first time in my life I came within an ace of fainting when I got out of the bath this morning. I have a bad headache, a general feeling of lassitude, and am bored out of my life by having nothing whatever to do.

By the beginning of August he was, if not fully recovered, at least well enough to retire to Oyster Bay and begin a survey of Leeholm. On the twentieth of that month he bought a further 95 acres of property for $20,000, bringing his total holdings to 155 acres.70This, in effect, gave him the whole of the estate he had coveted since boyhood; and even though he afterward resold two large tracts to Bamie, he could still consider himself monarch of all he surveyed.71 Before the month was out, Roosevelt was seen pacing across the grassy hilltop with his architects, Lamb and Rich, spelling out his “perfectly definite views” for their benefit. Out of this discussion came sketches, crystallizing later into approved blueprints, of an enormous three-story mansion, deep of foundation and sturdy of rafter, with no fewer than twelve bedrooms (poor pregnant Alice must have blanched at that specification) plus plenty of gables, dormers, and stained glass.72 Although Roosevelt protested he had nothing to do with exterior design, a reader of the blueprints could not help noticing certain resemblances to the Capitol at Albany.

![]()

ON 3 SEPTEMBER, Roosevelt kissed his wife good-bye, and loaded a duffel bag and gun case aboard the first of a series of westbound express trains. Alice’s emotions, as she watched his beaming, bespectacled face accelerating away from her, may well be guessed. Remembering how ill her “Teddy” had been when he first went West, she was not encouraged by the ravages of his recent illness, still markedly upon him. Last time, at least, he had had Elliott to look after him; now he was alone—for Commander Gorringe had decided, only four days before, not to go. Dakota, to her mind, was a place impossibly remote and inhospitable: “Badlands” indeed, roamed by dangerous animals and even more dangerous men. She could not have contemplated her husband arriving in Little Missouri, where he did not know a single human being, without consternation.73

Roosevelt was characteristically optimistic. By the time he reached Chicago he had gotten over his disappointment with Gorringe, and wrote Mittie that he was “feeling like a fighting cock” again.74 Changing to the St. Paul Express on 6 September, he began the second half of his 2,400-mile journey. When the train crossed the Red River at Fargo, the westernmost limit of his wanderings three years before with Elliott, he knew that he was leaving the United States, and heading west into the empty vastness of Dakota Territory. The landscape was so flat now, as darkness descended, that he was conscious of little but the overwhelming moonlit sky. About eight o’clock the huge spread of the Missouri swam out of the blackness ahead, slid beneath the train’s clattering wheels, and disappeared into the blackness behind. For hour after hour, flatness gave way to more flatness, and Roosevelt must surely have tired of pressing his face against the unrewarding glass. Perhaps he slept, lulled by the steady rush of air and wheels. If so, he missed seeing a corrugation on the western horizon, shortly after midnight; then, within minutes, all geological hell broke loose. On both sides the landscape disintegrated into a fantastic maze of buttes, ravines, mudbanks, and cliffs, smoldering here and there with inexplicable fires.75 Pillars of clay drifted by—more and more slowly now, as the train snaked down into the very bowels of the Badlands. A sluggish swirl of silver water opened out ahead; the train rumbled across on trestles, and stopped near a shadowy cluster of buildings. The time was two in the morning, and the place was Little Missouri.76

Roosevelt’s heels, as he jumped down from his Pullman car, felt no depot platform, only the soft crackle of sagebrush. The train, having no other passengers to discharge, puffed away toward Montana, and the buttes soon muted its roar into silence. Roosevelt was left with nothing but the trickling sounds of the river, and the hiss of his own asthmatic breathing. Shouldering his guns, he dragged his duffel bag across the sage toward the largest of the darkened buildings.77