2

Our main sources of information for Viking Age Heathendom are the four poems of cosmological and mystical content known as ‘The Seeress’s Prophecy’, ‘The Sayings of the High One’, ‘Vafthrudnir’s Sayings’ and ‘Grimnir’s Sayings’, which form part of the collection called the Poetic Edda; and the use made of these as illustrative material by Snorri Sturluson in the Prose Edda, a manual for the understanding of poetry which he wrote in Iceland in about 1220. As a lover of literature and a man with a strong sense of the importance of maintaining a respectful relationship to his cultural tradition, Snorri had become concerned that, after 200 years of active suppression of Heathen culture by the Christian Church, the survival of the large body of Old Norse poetry known as skaldic verse was threatened. The understanding of it depended to such a high degree on a knowledge of the myths and legends of the Old Norse gods and heroes that, unless something were done about it, they would shortly become incomprehensible to future generations of Icelanders. The chief problem was the use made by skaldic poets of elaborate figures known as kennings, periphrases which used details from the mythological stories of the adventures of the Norse gods and heroes to create names for familiar places, objects and people from other contexts that pushed them three or four metaphorical steps away from the original referent. The greater the distance, the greater the skill of the poet. The game for the listener was to untangle this dense thicket in order to reach the meaning of the poem. Though wildly anachronistic, the adjective ‘baroque’ suitably conveys the degree of their complexity.

It was always recognized that Snorri must have worked from a specific collection of poems, and in 1643 a vellum manuscript containing what turned out to be this collection came into the hands of an Icelandic bishop and scholar named Brynjolfúr Sveinsson. Dating from about 1270, it was itself a copy of an original dating to the early years of the same century. A few years later the bishop presented the collection to the king of Denmark, apparently as a way of restoring his own reputation and that of an unmarried daughter who had severely embarrassed them both by getting pregnant by a young priest.1 Since that time the manuscript has been known as the Codex Regius. Many of Snorri’s references in the Prose Edda were to details of Old Norse cosmology and myths that had remained obscure for later scholars, and the emergence of the Poetic Edda proved the key to unlocking many of them. The cosmological poems are difficult to date. Unlike skaldic poetry, which is by named poets, their creators were unknown. The unhurried devotion of ‘Vafthrudnir’s Sayings’ might suggest that it was composed well before its author perceived any threat to Heathendom from Christianity, perhaps early in the tenth century, while the urgent intensity of ‘The Seeress’s Prophecy’ suggests it may have been composed as an act of liturgical defiance much later on in the same century, when the threat was more clearly perceived.

The Prose Edda opens with a section called Gylfaginning, or the ‘Beguiling of Gylfi’, that describes how a legendary Swedish King Gylfi visited three Heathen gods in order to question them about the origins of the world. Snorri uses the replies King Gylfi receives to lay out the creation myth and cosmological structure of northern Heathendom. Gylfi learns that everything began in an empty chaos that contained a world of heat and light called Muspelheim, and an opposing dim, dark and cold world called Nifelheim. The two worlds were separated by a chasm, Ginnungagap. In the extreme physical forces that operated across Ginnungagap a giant named Ymir came into being. He was nourished by milk from the udders of a primordial cow, Audhumla. Audhumla next licked the salty stones around her into the shape of another giant, Buri. By an unspecified process Buri fathered a son, Bur, who wed a giantess, Bestla. The couple produced three sons, one of whom was Odin. Odin and his brothers created the physical world by killing Ymir and, in an act of prodigious violence, tearing the body apart and flinging the pieces in all directions. The giant’s blood became the sea, his flesh the land, his bones the mountains and cliffs, his skull the vault of the heavens. Later, as Odin and his brothers were walking by the sea, two logs washed up on the sands, and from these the gods created the first human beings by breathing life and consciousness into them. They named the first man Ask and the first woman Embla. Ask means ‘ash’, the meaning of Embla remains obscure.

Snorri’s further history of earliest things proceeds in a detailed and poetic vein, and to a modern mind unfamiliar with his world and his mindset it rapidly becomes confusing. Our confusion is compounded by the fact that in the Ynglingasaga with which he opensHeimskringla he provides a completely different, euhemeristic account of the origins of Odin and the Aesir, as Odin’s family of gods was known, in which Odin features as the chieftain-priest of a tribe living in the area around the Black Sea in the days of the Roman empire. This tribe migrated northwards through Russia and finally settled near Uppsala, on the coast of south-central Sweden, where Odin rewarded his followers in the traditional way by dealing out land to them.2 Rather than attempt to resolve these paradoxes, our aim here will be simply to try to abstract from Gylfaginning and the cosmological poems a general outline of the world-view that underpinned Viking Age Heathendom.

The cosmological world was conceived of as a flat circle divided into three distinct regions, each with its own characteristic set of inhabitants, and sharing a common centre.3 The innermost world was Asgard, where the Aesir lived, each in his or her own home. Odin lived in Valhalla, Thor in Trudheim, Freyja in Folkvang. As the god of war and warriors, poetry and hanged men, Odin’s work was to inspire poets, wage war and give fighting men courage in battle. Thor was responsible for natural phenomena such as wind, rain, thunder and lightning. These two were the most important male gods. In general terms Odin was the aristocratic god, worshipped by the dedicated warrior and the poet, while Thor was the god of the farmer and common man, especially popular in Iceland, Norway and Denmark. The eddic poem ‘The Lay of Harbard’ summarizes the distinction thus:

Odin claims the earls who fall on the field,

Thor only thralls.4

Freyja was skilled in sorcery and was the embodiment of female sexual power. Her brother Frey was the god of male potency, good weather, good harvests and fertile beasts. The image of him that stood in the great Heathen temple in Uppsala sported a large, erect phallus, and the 7 cm-high bronze figurine found at Rällinge in Södermanland, priapic as he sits cross-legged and naked save for a pointed cap, one hand holding his braided beard in a gesture of self-control, is almost certainly a depiction of him. Another god that looms large in the myths and the eddic poems was Loki, a son of giants adopted into the family of the Aesir. He was also Odin’s troubled - and troubling - half-brother whose amoral and chaotic fickleness and lack of discipline introduced a dangerous unpredictability into many of the Aesir’s enterprises.

Beyond this inner region was Midgard, domain of the humans. The word meant ‘home or farm in the middle’ and conveyed clearly the humans’ sense of being located midway between the gods in Asgard and Utgard, or ‘the outer place’, the outer rim of the disc-world, a region inhabited by giants and other elemental beings associated with untamed chaos. Between Midgard and Utgard lay a sea, home to an enormous serpent which encircled the world and kept it bound together by biting on its own tail.

The vertical axis of the flat, round world was an ash-tree named Yggdrasil, connected to the sky at its crown, and at its roots penetrating to a subterranean realm that included a well, known as Urd’s Well, where the gods held their assembly meetings and where three females, known as Norns, spun out the destinies of humans and gods alike. The role of Yggdrasil in this cosmology was to assure the inhabitants of Midgard that there was a centre to the world, and that all things were connected, appearances to the contrary, despite the ceaseless struggle between a will to order, represented by the gods of Asgard, and the entropic lure of chaos, represented by the giants and creatures of Utgard. The tree symbolized the cycle of life, drawing water from the well at its roots and returning it to the world as nourishment in the form of dew.

Though Utgard was a threatening and frightening place to be, even for the gods, it was understood that in the chaos within its borders lay the raw materials necessary for the learning of new skills and the creation of valuable treasures that the Aesir could hand on to the humans of Midgard. The story of how Odin forced the secrets of the art of writing runes from the reluctant terrain of this mental region is a dramatic illustration of the view that learning, knowledge and progress had to be fought for and suffered for. In a famous interlude in the long wisdom poem ‘The Sayings of the High One’, Odin describes how he hung from the branches of Yggdrasil:

I know that I hung on a windy tree

nine long nights,

wounded with a spear, dedicated to Odin,

myself to myself,

on that tree of which no man knows

from where its roots run.

Despite his status as the god of Hanged Men, it may be that on this occasion he is to be imagined as dangling upside down by the foot, as the ‘Hanged Man’ of the medieval Tarot is depicted.5 This simplifies the logistics of the theft that follows:

No bread did they give me nor a drink from a horn,

downwards I peered;

I took up the runes, screaming I took them,

then I fell back from there.

Proudly Odin relates the advances that his suffering has paid for:

Then I began to quicken and be wise,

and to grow and to prosper;

one word found another word for me,

one deed found another deed for me.6

These skills were duly passed on to the inhabitants of Midgard. The story emphasizes the thirst for knowledge that was one of the most striking of Odin’s characteristics, and the lengths he would go to in order to get it. In another story Odin requested a drink from a well of wisdom maintained by a mysterious giant named Mimir. When Mimir suggested an eye as the price of his assent Odin did not hesitate to pay. Odin’s curiosity about the world, and his willingness to take enormous risks to satisfy it, are among the characteristics that distinguish him most sharply from the omniscient and omnipotent God of the Christian conception. Another is that the Aesir knew they were mortal. Odin’s search for knowledge was very often a driven curiosity aimed at finding out more about how their deaths would occur.

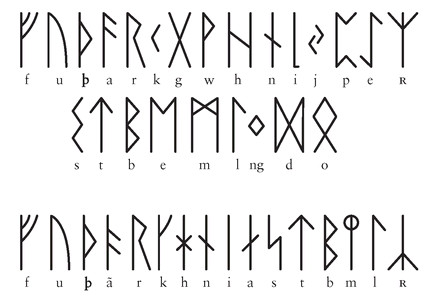

Above: The older futhark, consisting of 24 runes, was in use for about 700 years after the birth of Christ. Below: A rationalized form using only 16 runes was in use by the end of the eighth century.

In some cases these tales of the gods on their forays into Utgard to outwit the giants and wrest secrets and treasures from them also give an insight into the lost astronomy of the Viking Age. Odin’s sacrifice of an eye is likely the remnant of a story once told to explain why the sky only has one eye, in the form of the sun. The sibyl in this verse from ‘The Seeress’s Prophecy’ seems to be referring to the rising of the morning sun:

I sat outside alone; the old one came,

The lord of the Aesir, and looked into my face:

‘Why have you come here? What would you ask me?

I know, Odin, how you lost your eye:

It lies in the water of Mimir’s well.’

Every morning Mimir drinks mead

From Warfather’s tribute. Seek you wisdom still?7

More directly explanatory is a story of the constellation known to the Vikings as ‘Thiazzi’s Eyes’. As a result of a piece of intemperate behaviour by Loki, the gods’ apples of eternal youth fell into the hands of a giant named Thiazzi, whom they had to kill in order to recover them. When Thiazzi’s daughter Skadi turned up at Asgard looking for revenge for the killing, Odin offered her compensation in the form of celestial immortality for her father, throwing his eyes into the night sky where they became stars to which he gave the name ‘Thiazzi’s Eyes’. These two stars are probably to be identified with Castor and Pollux in the constellation Gemini of our own astronomy.8 The tale of Thor’s duel with the giant Hrungnir is another myth with astronomical content. Following his success in the duel, Thor helped out a dwarf named Aurvandil by carrying him across the primordial river Élivagar in a basket on his back. When Aurvandil complained of frostbite in one of his toes Thor broke it off and threw it into the sky, where it became the star known as ‘Aurvandil’s Toe’, corresponding in our astronomy to Alcor in Ursa Major.9 Thor told the story to Aurvandil’s wife Groa as she worked to remove a splinter of broken whetstone lodged in Thor’s head after the duel. Groa became so excited at his news that she abandoned the job and never returned to it, leaving poor Thor with a chronic headache. This whetstone splinter in his head was said to be the nail that held Yggdrasil fixed to the sky. Its modern astronomical correspondent is probably our Polaris, the North Star in Ursa Minor, then as now the star around which the whole of the northern night sky seems to revolve. Viking Age Scandinavians must have had many more such explanatory tales, but the early scribes of the Christian era who had occasion to mention the stars and constellations in their writings preferred to use the Latin names, with the result that the native names disappeared, all but those few which survived down into Snorri’s time, securely embedded in the Eddic poetry.

Probably as a result of his pre-eminence as the god of poets, Odin had over 150 names, but the most significant of them was simply ‘All-Father’. Most of the gods were his children by various mothers. Some of them were Aesir, like himself. Others, like Thor’s mother Jord (‘Earth’), were giantesses from Utgard. That the gods of Asgard were willing to engage in such fraught unions with their enemies underscores Midgard’s perception that social and technological advances could only be achieved by risk-taking. Among Frey’s significant earthly progeny was his son by the giantess Gerd, who became the first king of the Yngling dynasty that ruled over the Swedes and, in later, historical time, over the Norwegians of the Vestfold region in the south of the country; Sæming, founding father of the long line of powerful chieftains who ruled over the Lade district in the region of Trondheim in present-day Norway, was likewise the son of a union between a god and a giant, as was Skjold, the legendary first king of the Danes. This genealogical link back to divinity was important because it legitimized the claims to power of the Scandinavian kings who ruled in later, historical times.10

This world of Asgard, Midgard and Utgard, with Yggdrasil at its centre, can be seen as a macrocosmic image of the world of a typical, Viking Age homestead. At the centre stood the main farmhouse building and outhouses, ringed around by a belt of cultivated land and pasture. Beyond this lay the rimmed horizon of uncultivated wilderness. Close by the main house stood a tree, known in Sweden as a vårdträdet and in Norway as a tuntreet or ‘house-tree’. Each family cultivated a mystical association with its ‘house-tree’ that served as a symbol of continuity through the generations.11 The circle in the physical form of a ring had particular significance in Viking Heathen culture. As a symbol of loyalty and honesty it appears in an entry in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for 876, noting a settlement between the Christian King Alfred of Wessex and three Viking chieftains. The Chronicle tells us that the chieftains ‘swore him oaths on the sacred ring’ that they would leave his kingdom at once, and that this was ‘a thing which they would not do before for any other nation’.12 A verse in ‘The Sayings of the High One’ expresses in negative fashion the binding gravity of such an oath:

Odin didn’t honour his oath on the ring

What good is any pledge he gives?

Suttung died of a poisoned drink,

And Gunnlod grieves.13

The reference here is to the story of how Odin obtained the mead of poetry from the giant Suttung, having seduced his daughter Gunnlod, to whom Suttung had entrusted the mead. This, like the secret of the runes, is another example of a treasure stolen by an inhabitant of Asgard from the hazardous mental region of Utgard for the benefit of the humans of Midgard. Odin broke his word to Gunnlod because the consuming need for poetry justified any means to gain possession of it. This ruthlessness in pursuit of his own ends made Odin feared and admired among his followers and, as we shall see, Viking warriors abroad would very often take their cue from him in their dealings with the Christian kings of England and Francia.

The ring seems also to have been a symbol of eternal recurrence, illustrated by one of Odin’s magical treasures, the ring Draupnir, made for him by the dwarves of Utgard, that dripped eight new rings every ninth night. The ring also played an important role in the sanctification of Heathen gatherings. According to the Book of the Settlements, a ring was to lie on the altar of every Icelandic chieftain and he was obliged to wear it on his arm at every assembly meeting over which he presided as chieftain-priest. The same obligation is also referred to in a description of a chieftain-priest’s temple contained in the Eyrbyggja Saga.14 This is a late source, probably composed about the middle of the thirteenth century, and though the usual reservations about reliability have to be made it is evidently the work of an author with a great interest in the early history of his own country. He mentions a table in the centre of the temple with a ring lying on it. Sacrifice, varying in intensity from fruit to the offering of a life, was a central means of communication between followers and gods, and beside the ring stood a bowl in which the blood of a sacrificed animal would be collected. Next to it lay a twig that may have been dipped into the bowl and shaken over the gathering as a way of binding it together, much as Moses is said to have done in the Old Testament.15 It may also have been used to create a random pattern of blood-spots in which the chieftain-priest might read the oracular response to an important question.

The sites of two major festivals are known, one at Leire in Zealand, in Denmark, and the other at Uppsala in Sweden. Both were enneadic events, announcing a mystical attachment to the number nine. At the festivals at Leire ninety-nine humans and as many horses, dogs and roosters were sacrificed. Though he did not see the building himself, Adam of Bremen reported a description of the temple at Uppsala in his Gesta Hammaburgensis as a sumptuous palace, richly decorated in gold, where people gathered to make sacrificial offerings before a trio of images, with Thor at the centre, flanked on either side by Odin and Frey. Each day for nine days the males of nine species, including humans, were sacrificed by hanging from trees in a small copse not far from the temple. One of the textile remains from the Oseberg burial appears to show such a scene, with numerous bodies dangling from the branches of a large tree. From Saxo’s passing reference to ‘the clatter of actors on the stage’ it seems the rituals also involved the performance of some kind of cult drama.16 Songs were chanted at the Uppsala festivals which were reported to Adam of Bremen by his informant but which the cleric found so obscene he declined to record them.17 ‘Haustlong’, by the late ninth-century Norwegian Tjodolf of Hvin, is a rare example of a skaldic poem that incorporates lines of spoken dialogue which may have been part of such a cult drama.18 Of the actual formalities of worship, however, we know little. The only prayer of direct address to the gods is the brief invocation in ‘The Lay of Sigrdrifa’:

‘Hail to the Aesir! Hail to the goddesses!

Hail to the mighty, fecund earth!

Eloquence and native wit may you give us

And healing hands while we live!’19

Archaeological evidence that human sacrifice was practised does exist, but is not extensive. Much depends on the interpretation of the finds. In the 1990s excavations were carried out by a team under Lars Jørgensen of the National Museum of Denmark on what was originally thought to be the rubbish dump of a chieftain’s farm on a site at Lake Tissø, in Western Zealand. The team unearthed an increasingly confusing mixture of buried silver, gold, and animal and human bones, which eventually, along with the illogical location of the dump on a hilltop, persuaded them to reinterpret the site as a place of sacrifice.20 At Lillmyr in Barlingbo, on Gotland, close to the modern town of Roma and near to where the island’s main assembly formerly met, an excavated pit that contained the mingled remains of humans, horses and sheep has been tentatively identified as a place of human sacrifice.21 There is more potential evidence in scenes depicted on the Hammars picture-stone from Lärbro on Gotland, dated to 700-800.22 A man carrying a shield seems to be tied by his neck to the branch of a tree which has been tethered down. When the tree is released he will be jerked from his feet. The main focus of the scene, however, is the small figure, perhaps a dwarf or child in the centre of the panel, who lies face downward upon a platform of some kind. Above the figure hangs a valknut, three triangles that mark the victim as dedicated to Odin, bound in the same impossible perspectual framework that so fascinated the Dutch graphic artist M. C. Escher.

A separate category of human sacrifice involved the killing of slaves to serve their dead masters in the afterlife. Ibn Fadlan’s account of the funeral on the Volga to which we referred earlier included a description in pathetic detail of the fate of such a slave, cajoled into volunteering to join her owner in his funeral ship with the promise of a few days of special treatment and a great deal of alcohol. After her ritual rape by the chieftains’ companions she was handed over to an old woman known as the ‘Angel of Death’ to be strangled and stabbed before being carried on to the funeral ship beside him, along with his shoes, his weapons and the other items he would need in his next life. Most double graves from the Viking Age which show an apparent inequality in the status of the dead are interpreted as being those of master or mistress and slave. Of two male skeletons found in a single grave at Stengade, in Langeland in Denmark, one was buried with a spear and the other, bound and decapitated, has been identified as his slave. The Viking Age grave at Ballateare, on the Isle of Man, also contains two bodies, one a male buried with his sword, shield and three spearheads, the other a female with the top of her head sliced off, the mark of a ritual death.23 Sacrifice was so central to the practice of Heathendom that the law codes of the Christian-era culture that eventually displaced it in the Scandinavian lands found it necessary expressly to forbid the practice: ‘Nor may we sacrifice,’ said the Norwegian Gulathing Law, ‘not to Heathen gods nor to mounds nor piles of stones.’24 The Gotland Gutalagen was similarly trenchant: ‘All sacrificing is strictly forbidden as are all practices formerly connected with Heathendom.’25 Equally dogmatic was the Uppland Law of the eastern Swedes: ‘No one shall sacrifice to false gods, nor worship groves nor stones.’

These greater and smaller feasts were important social and religious institutions that bound communities together under their chieftain-priests in symbolic acts of feasting, eating and worshipping. They were also occasions on which the important matter of the law was dealt with. The Old Norse gods were not ethical beings. Ethics were the province of man and the law. The word ‘synd’ (sin) does not appear in any Viking Age literary source until as late as about 1030, when the poet Torarin Lovtunge in his ‘Glælognskvida’ described the Norwegian saint-king Olav Haraldson as having died a ‘sinless death’.26 Viking Age ethics were based on the opposition of shame and honour. Openness was the keynote of the oldest surviving codes, and though these were written down in post-Heathen times there is no reason to doubt that they convey the spirit of the ages that preceded them.27 Whether it be a business deal or a divorce, the requirement of the law for a large number of witnesses was always present, underscoring the role of shame in discouraging anyone inclined to go back on an agreement entered into so publicly. The distinction drawn between crimes committed openly and in secret marks an even clearer example of the use of shame to maintain social order. That bad actions are not always the work of bad people was recognized by the requirement that manslaughter be declared in front of witnesses within a specific time after the killing. The law obliged the killer to report the deed to the first person he or she met afterwards, although they could, if they wished, avail themselves of an exemption that allowed them to pass by two houses - but not a third - if they suspected that relatives of the dead person lived there, before making their confession. If the proper procedures were followed, the killing could be atoned for by compensation.28 Murder, on the other hand, was a dishonourable act, committed in secret, unacknowledged and liable to set in train a cycle of revenge killings. An Old Norse proverb delivered the legal distinction poetically: náttvíg eru morðvíg (‘killing by night is murder’). Unannounced killings were, by definition, murder.

Communal responsibility was further promoted by laws that made personal involvement mandatory in certain circumstances: any persons who witnessed an accidental death and failed to report it to the family and heirs of the deceased were likely to find themselves facing an accusation of murder. One section of the law of the west-Norwegian Gulathing, whose writ ran from Stad in the north to Egersund in the south, dealt with a killing done in an ale-house. Whether it happened by daylight or by firelight, all those present were obliged to join in apprehending the culprit. Failure to do so entrained a compensation payment to the relatives of the victim, making it in the financial interests of all present to ensure the killer was caught. A thief surprised in the act of stealing might legally be killed, but not a robber, whose crime was committed face-to-face. The rationale, in this culture of self-reliance, was that the victim of a robbery had in principle at least a fair chance of preventing it. Under the laws of both the Gulathing and the Frostathing, at which the people of the Trøndelag region gathered to do business, the punishment of criminals was likewise a communal responsibility. A thief convicted of a petty offence had to run a gauntlet of stones and turf. The thirteenth-century Bjarkøyretten that regulated local affairs in Trondheim even stipulated the fine to be paid by anyone who failed to throw something at the thief.

The practice of oath-taking in courts of law likewise showed the strong natural inclination towards the involvement of the whole community. Depending on the seriousness of his or her crime, an accused person might be asked to give one of four grades of oaths requiring the support of, respectively, one, two, five or eleven compurgators or supporters, with a twelve-fold oath being used in the extreme case of murder. They were not necessarily swearing to anything that had a bearing on the facts of the case in hand. Essentially they were character witnesses, affirming their belief in the honesty of the person giving the oath. Strict rules governed the process of oath-taking, and any breach of them made the oath invalid.

The most striking deviation from this adherence to communal responsibility involved kings. The price paid by some early Yngling kings for claiming descent from the gods was to be blamed when the gods turned against their followers and blighted the crops, emptied the seas of fish or in some other way brought famine and ill-luck on the tribe. Snorri tells us that in the reign of the legendary King Domaldi in Sweden an enduring famine occurred that occasioned a hierarchy of sacrifices. It began with oxen, proceeded to men and, when none of this had any effect, culminated in the sacrifice of the king himself. Nor were substitutes acceptable: Gautrek’s Saga, preserved in a number of manuscripts dating from the early fifteenth century, tells the remarkable tale of an attempt to regain Odin’s favour by the mock-sacrifice of a certain King Vikar, whose name in Norwegian means ‘substitute’. The guts of a slaughtered calf were looped around his neck instead of rope, and tethered to a twig. Instead of the point of a spear, a blade of straw was jabbed against his side. The dedication was announced: ‘Now I give you to Odin.’ Instantly the straw turned into a spear that penetrated the king’s side, the tree-stub he was standing on turned into a stool that tumbled over, and the intestines became a stout rope. The twig flexed and thickened and the king was dragged high into the air. The similarities to the scene described in pictures on the Hammars stone are striking.

Domaldi’s son Domar was luckier than his father. Snorri tells us Domar

ruled for a long time, and there were good seasons and peace in his days. About him nothing else is told, but that he died in his bed in Uppsala, was borne to Fyrisvold, and burned there on the river bank where his standing-stone is.29

For a king to die peacefully in this way was the sign of a happy and prosperous reign. This explains the apparent anomaly in Snorri’s biography of the euhemeristic Odin, in which this greatest of all warriors is reported to have died in his bed.

As these stories show, Scandinavian Heathens were fatalists who nevertheless believed that the gods might be prepared to change their fates if only the gifts offered were rich enough. This belief that fate might be changed also manifested itself at the day-to-day level, where the sorcerer’s art of seid was much prized as a way of trying to influence the working of fate in the personal sphere. Seid was a form of divination closely related to shamanism that sought access to secret knowledge of hidden things, whether in the mind or in the physical world. In its ‘white’ form it could be used to heal the sick, control the weather and call up fish and game before the hunter. Its ‘black’ form had the power to raise the dead, curse an enemy and blight his land, raise up storms against him and destroy his or her luck in love and in war. In both his euhemeristic and his divine manifestations Odin was a master of the art. His skill as a shape-changer enabled him to transform himself into a fish, a bird, a beast or snake and transport himself over vast distances. It gave him knowledge of the future and the power to enter grave-mounds, bind the dead and take from them whatever treasures he wanted. He could control fire with it and order the wind to change direction. Seid gave him the power to strike his enemies in battle blind or deaf, blunt their weapons and freeze them in terror. He could imbue his followers with such strength and courage in battle that they turned into raging berserks, wild men able to kill with one blow, as strong as bears and as savage as wolves, disdaining the use of armour and in their ecstatic fury impervious to all harm. In Snorri’s words:

From these arts [Odin] became very celebrated. His enemies dreaded him; his friends put their faith in him and relied on his power and on himself. He taught most of his arts to his priests of the sacrifices, and they came nearest to him in sorcery. Many others, however, occupied themselves much with it; and from that time sorcery spread far and wide, and continued long.30

‘He and his temple priests were called song-smiths, for from them came that art of song into the northern countries,’ Snorri adds, and perhaps these songs were the chants that Adam of Bremen judged too shocking to repeat in his history. Their importance in Heathen ritual is reflected in the prohibition in the post-Heathen Gulathing law against galdresang or ‘spell-chanting’, which was punishable by banishment.

Despite the powers seid conferred on its user, Snorri tells us that in time it was felt to compromise masculinity so profoundly that it presently became the province of women, and possibly of homosexual men. In a disapproving reference in the Gesta Danorum to the ceremonies at ‘Uppsala in the period of sacrifices’, Saxo Grammaticus writes of the ‘soft tinkling of bells’ and the ‘womanish body movements’ of the participants. Like Adam he too mentions the role of chanting. In one of the Eddic poems, ‘Loki’s Quarrel’, in which Loki ritually heaps insults upon each of the Aesir, it is for his feminizing practice of seid that Loki attacks Odin when his turn comes:

But you once practised seid on Samsey,

and you beat on the drum as witches do,

in the likeness of a lizard you journeyed among

mankind,

and that I thought the hallmark of a pervert.31

An account in the twelfth-century Historia Norwegie of a shamanistic seance among the Lapps may shed some light on the sexual ambiguity of the sort of performance Loki was mocking:

Once when some Christians were among the Lapps on a trading trip, they were sitting at table when their hostess suddenly collapsed and died. The Christians were sorely grieved but the Lapps, who were not at all sorrowful, told them that she was not dead but had been snatched away by the gandi of rivals and that they themselves would soon retrieve her. Then a wizard spread out a cloth under which he made himself ready for unholy magic incantations and with hands extended lifted up a small vessel like a sieve, which was covered with images of whales and reindeer with harness and little skis, even a little boat with oars. The devilish gandus would use these means of transport over heights of snow, across slopes of mountains and through depths of lakes. After dancing there for a very long time to endow this equipment with magic power, he at last fell to the ground, as black as an Ethiopian and foaming at the mouth like a madman.32

The great power attached to being a sorcerer is one possible explanation for the sumptuous nature of the Oseberg ship-burial.33 Among the arguments advanced for identifying one of the women as a sorceress are the find of a peculiarly ornate kind of staff associated with witchcraft, and four seeds of cannabis sativa. Such an identification might also shed light on the hitherto unexplained function of the iron wrangle or rattle found in the grave - four iron hoops threaded on to a barred handle that might have been vigorously shaken to drive away malignant spirits. Medical tests carried out on the remains of the women in 2007 and 2008 showed that the older of the two suffered from a hormonal imbalance which probably rendered her sterile, at the same time promoting a strong growth of hair, including facial hair. At the age of about fifteen she appears to have sustained severe damage to her left knee, perhaps as the result of a bad fall, from which she emerged a semi-invalid who must have walked with a heavy limp. Professor Per Holck’s analysis has shown a striking over-development of the musculature of her upper arms consistent with the long-term use of crutches. Perhaps this set of physical abnormalities, combined with a striking personality, defined her status as a sorceress for a community that saw them as the visible signs of her rare and magical ability to inhabit the worlds of both male and female.34

As part of the ritual of worship, as transport, as beast of burden, as food and as companion, the importance of the horse in the culture of northern Heathendom can hardly be overestimated. Viking Age cosmology fancied the sun drawn across the sky by two of them, Alsvinn, ‘the Speedy’, and Arvakr, ‘the Wakeful’. Odin rode on an eight-legged grey named Sleipnir that was as quick over sea as land, and the identification of the ship as ‘the horse of the sea’ was one of the staple metaphors used by skaldic poets. Much like the modern car, the horse was a status symbol. A verse in ‘The Sayings of the High One’ made the point in negative fashion:

Don’t be hungry when you ride to the Thing,

be clean though your clothes be poor;

you will not be shamed by shoes and breeches,

nor by your horse, though he be no prize.35

The Viking Age horse had a shorter back and thicker neck than the modern horse, and with an average height of just under 2 metres it was not much bigger than a large pony of today. The modern Icelandic horse is its direct and almost unchanged descendant, with its characteristic thick mane and tail and five gaits: walking, trotting, galloping, flying, and the unique fifth gait known as tolting, a sort of running walk with a low knee-action which enabled horse and rider to cover long distances without tiring. This was particularly useful in Iceland, where the lack of timber for ship-building meant that riding rather than sailing was the preferred method of travelling along the coast. The horse played a large part in the sporting life of these people. In the Saga of Sigurd the Crusader and his brothers Eystein and Olaf, Snorri describes, with his usual gusto, a series of races run for a wager between King Harald Gille of Norway on foot and his nephew Magnus Sigurdsson on horseback. The fact that Harald emerged as winner tells us that, for all its strength, good nature and endurance, the horse was small and not especially quick.36 Horse-fighting was a popular sport and the drama of one of the most frequently anthologized short stories from Iceland, Thorstein the Staff-struck, derives from tempers lost following an incident during a horse-fight. Horses were raced against each other too. In England the names Hesketh Grange, in Thornton Hough, and Heskeths at Irby, in the Wirral, both derive from Old Norse hestur, ‘horse’, and skeid, ‘track’, and both preserve the memory of Viking Age racetracks at these locations.37

As a mount in battle the horse was less favoured. The bridle-bits found in Viking Age graves are of the type known as snaffle-bits, with a jointed central mouthpiece and rings on either side, which made them unsuitable for use in battle. Riders on the Gotland picture-stones are depicted without stirrups, which again would have made fighting from horseback difficult. The horse might be used as a means of transport to reach the field of battle, but once there the warriors would dismount and engage with the enemy on foot. The Oseberg tapestries that originally probably hung on the walls of the burial chamber featured multiple depictions of horses, and horses’ heads were carved into the bedposts and on the ends of the burial-chamber crosspieces. A literary reflection of this degree of devotion is found in the late thirteenth-century masterpiece Hrafnkels Saga, which describes the special relationship between the farmer-chieftain Hrafnkel and his stallion, Freyfaxi. Hrafnkel declares Freyfaxi sacred to Frey and forbids any man to ride him. Though we learn no further details of the arrangement it binds Hrafnkel sufficiently to kill a shepherd boy who one day disobeys the ruling.

The taboo exercised by Christian writers on matters relating to the cult of the horse will have obscured a great deal of material on the subject, but strewn across the literature are stray reminiscences of the status of the horse as an image of potency and fertility.The short story known as the Völsa tháttr describes how the Norwegian King Olav Haraldson and two of his men arrived at a remote farm while out travelling.38 As they sat to dine with their hosts the farmer’s wife took a stallion’s penis from the linen wrapping in which she stored it, using an onion as a preservative. This object, which she called Volsi, was passed from hand to hand among the guests to the accompaniment of a repetitive chanting. When the king’s turn came he brought proceedings to an abrupt halt by throwing Volsi to the family dog, which promptly ate it. Some form of phallic horse-worship also appears to be referred to in a poem of the purposefully offensive type known as nid, in which the poet, the Norwegian King Magnus the Good, mockingly accused his Heathen opponent, Sigurd syr, of having built ‘a ring of stakes around a horse’s penis’.39

One of the most remarkable testaments to the importance of the horse in Heathen culture is found in a passage in The Topography of Ireland. Here the Welsh historian Giraldus Cambrensis describes a king-making ceremony among the Heathens of Kenel Cunill, in a remote part of northern Ulster.40 At a gathering of the tribe a white mare is brought into the ring of people and an act of bestiality involving the king and the mare takes place at which the king becomes, by association, a stallion. The mare is then killed and dismembered and a broth made of her blood and flesh. After the king has bathed in it, he and the other members of the tribe eat the flesh and drink the broth. The account derives from the extreme end of the spectrum of what Christians might believe about Heathens; but if it represents only an isolated case it might yet be enough to explain the degree of horror felt by Christians at the practice of eating horse-meat. As we shall see, on two occasions in particular the part played in the hallowing of the Heathen assemblies by the ritual preparation and consumption of horse-flesh marked a dramatic highlight in the religious tensions between followers of the old faith and adherents to the new, the first involving an early attempt by King Håkon the Good to impose the Christian faith on his fellow-Norwegians, and the second as part of the dramatic series of events surrounding the acceptance by Icelanders of Christianity as their official religion in the year 999.

So great is our debt to Snorri Sturluson for the insight he gives us into how Viking Age Heathens explained the facts of life and death to themselves that there is a danger of our assuming that he has, in fact, told us all there is to know on these subjects. He gives us something approaching a coherent narrative, and that fact alone ought to make us a little wary. Grave-mounds are commonplace to him, but there is nothing in either Heimskringla or the Prose Edda to suggest that he was aware that the dead inside them may have been buried in ships. None of his landscapes of Heathen death involves a place that must be reached by water, and in terms of understanding the thought that lay behind them, what he tells us sheds little light on the specific cases of the Oseberg and Gokstad burials. The great wealth of these two burials might be in conformity with one of the laws Snorri attributes to the euhemeristic Odin, that those who joined him in Valhalla should enjoy there what they had buried in the earth with them; but both burials are then in defiance of an injunction in the same set of laws to cremate the dead and their possessions.41 The choice of inhumation rather than cremation may have been a sign that the dead person had been a particularly successful leader. So successful was the reign of King Frey, the founder of the Yngling dynasty, who ruled in Uppsala shortly after the death of Odin, that when he died his closest followers kept the death a secret, buried his body in a mound and told people that he was still alive and looking after them.42Ultimately the lack of consistency only comfirms the futility of expecting it. As Anthony Faulkes, the translator and editor of Snorri’s Prose Edda puts it, the Heathen religion was probably never understood systematically even by those who practised it. From the Saga of the Jomsvikingswe know that people cultivated supernatural personal helpers whose powers they placed above those of any of the Aesir. In a desperate attempt to change the course of the crucial sea-battle at Hjórungavág in about 986, Håkon the Bad, a Norwegian Earl of Lade, sacrificed his nine-year-old son Erling to a personal goddess, Thorgerdr Holgabrudr, who rewarded him with a hailstorm that turned the tide of battle in his favour.43 The tenth-century Icelandic priest-chieftain, Thorgeir Ljosvetningagodi, practised an informal worship of the sun, and when he felt death approaching asked to be carried out into its light. There were probably other forms of worship, other objects of devotion of which we know nothing.

Even with all these uncertainties, however, one thing is abundantly clear: whatever else it was, northern Heathendom was not the absence of a culture. Viking Age Scandinavians had their own cosmology, their own astronomy, their own gods, their own social structure, their own form of government and their own notions of how best to live and die. By the middle of the eighth century, regional power centres had grown up on the south-west and south-east coasts of Norway, around the kings and chieftains of Avaldsnes on the island of Karmøy, near Haugesund in Rogaland, and those kings of Vestfold in the Tønsberg area who claimed descent from the Yngling dynasty.44 Confirmation that there was high-level communication between these regions came in 2009 with dendrochronological analysis which showed that the timber used to build the Oseberg ship in 820 came from the same south-west coastal region as that used for the three ships found at the end of the nineteenth century in the Storhaug and Grønnhaug mounds at Karmøy. Tree-ring dating also indicates that the ship in the Grønnhaug mound was built in 720, and both large and small ships in the Storhaug mound in 771.45 All three were propelled exclusively by oars. The Storhaug ship was interred in late 779 and is the youngest large, man-powered rowing-ship we know of. The Oseberg ship remains the oldest known example of the classic, sail-powered Viking longship. The conclusion is that at some point in the forty years that separate the building of the two, a remarkable technological breakthrough occurred in the construction and use of sail, which greatly increased the speed longships were capable of reaching and removed much of the physical burden of rowing from their crews. The breakthrough would have a dramatic effect on the development of European history over the next three centuries.