3

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that extraordinary weather conditions preceded the raid on Lindisfarne in 793, high winds and lightning flashes that were afterwards understood to have been portents - ‘and a little after that in the same year on 8 January the harrying of the heathen miserably destroyed God’s church in Lindisfarne by rapine and slaughter’.1 Experiments with modern reconstructions have shown that in good visibility a Viking longship at sea could be seen some 18 nautical miles away. With a favourable wind, that distance could be covered in about an hour, so that is perhaps all the time the monks had to prepare themselves for the attack.2 It is unlikely they did anything at all, for the written records of the raid present it as completely unexpected:

We and our fathers have now lived in this fair land for nearly three hundred and fifty years, and never before has such an atrocity been seen in Britain as we have now suffered at the hands of a pagan people. Such a voyage was not thought possible. The church of St Cuthbert is spattered with the blood of the priests of God, stripped of all its furnishings, exposed to the plundering of pagans - a place more sacred than any in Britain.3

The extract is from a letter, written in the wake of the attack, to King Ethelred of Northumbria by Alcuin, one of the leading Christian figures of the age. Born in Northumbria, Alcuin had been a monk in York before accepting an invitation in 781 to join Charlemagne at his court in Aachen, where he soon played a prominent role in the revival of learning known as the Carolingian renaissance. He knew both the monastery at Lindisfarne and many of its leading figures well.

A third account of the atrocity by Simeon of Durham, the early twelfth-century English chronicler, adds detail that may come from a lost Northumbrian annals:

In the same year the pagans from the northern regions came with a naval force to Britain like stinging hornets and spread on all sides like fearful wolves, robbed, tore and slaughtered not only beasts of burden, sheep and oxen, but even priests and deacons, and companies of monks and nuns. And they came to the church at Lindisfarne, laid everything waste with grievous plundering, trampled the holy places with polluted steps, dug up the altars and seized all the treasure of the holy church. They killed some of the brothers, took some away with them in fetters, many they drove out, naked and loaded with insults, some they drowned in the sea . . .4

A fourth document, of unknown date but possibly near-contemporary, is the Lindisfarne stone. This shows seven marching men in profile. Perhaps in response to the constraints of the semi-circular stone, those at the front and the rear of the column are unarmed. Of the central five the first two are carrying axes, the three behind them swords. The axes are distinct from one another in shape and are held about halfway up the handle. The men wear tunics that reach to about midway down the thigh and seem to have some kind of padding or reinforcement around the midriff. They wear tight-fitting leggings and heavy shoes that appear to be ankle-high. They march with stiff necks and chests out, their weapons raised one-handed above their heads as though about to sweep down. The stylization is strikingly similar to the image of warring men depicted on a panel of the Gotland Hammars picture-stone. The Hammars stone is the more accomplished work of art, but there is a telegrammatic crudeness about the Lindisfarne stone that seems to convey more directly and urgently the brutality of face-to-face violence. Unlike the men on the Hammars stone, the Lindisfarne warriors are not carrying shields. It is as though they were not expecting to encounter resistance.

‘Such a voyage was not thought possible,’ Alcuin wrote. And in a long poem on The Destruction of Lindisfarne he once again conveyed the impression that the attackers were an unknown quantity. His lute groans sadly, he writes, at the appearance of this ‘pagan warband arrived from the ends of the earth’. And yet, in that same letter, he rebuked Ethelred and his people in terms that wholly contradict the impression that the raid came as a surprise: ‘Consider the luxurious dress, hair and behaviour of leaders and people,’ he urged the king. ‘See how you have wanted to copy the pagan way of cutting hair and beards. Are not these the people whose terror threatens us, yet you want to copy their hair?’5 The sentiments are similar to those expressed in a letter, fragmentary and incomplete, from an unknown sender to an unknown recipient or recipients, criticized for

loving the practices of Heathen men who begrudge you life, and in so doing show by such evil habits that you despise your race and your ancestors, since in insult to them you dress in Danish fashion with bared necks and blinded eyes. I will say no more about that shameful mode of dress except what books tell us, that he will be accursed who follows Heathen practices in his life and in so doing dishonours his own race.6

Much as the sixth-century British monk Gildas, some 300 years before him, had interpreted the invasion of Alcuin’s own Anglo-Saxon and Heathen forebears as God’s punishment on Britons for their lax observance of the Christian way of life, so did Alcuin discover in the Vikings God’s scourge on a lax and degenerate Northumbrian clergy and court. In several letters written after the attack he painted a dismaying picture of contemporary monastic life, inveighing against drunkenness and the practice of inviting ‘actors and voluptuaries’ to dine at the monastery tables instead of the poor, and condemning the practice of entertainment at mealtimes. In place of the sounds of the harp, accompanying ‘the songs of the heathens’, he suggested readings from the Bible and the Church fathers. ‘For what has Ingeld to do with Christ?’ he added, incidentally condemning the popularity in monasteries of Beowulf, a cultural betrayal which must have struck him as even more dismaying than the fashion at King Ethelred’s court for Heathen hairstyles.7The unavoidable conclusion of all this is that at the time of the Lindisfarne raid Alcuin and the people of Northumbria were already quite familiar with their Scandinavian visitors. What was new was the violence.

Attempts to provide a single aetiology for the beginning of the Viking Age soon run across difficulties similar to those posed in trying to set its parameters. The suggested causes are numerous and often cancel each other out. The sheer geographical spread of the Scandinavian homelands means that a suggested cause for the activities of Norwegians on the west coast of the peninsula across the North Sea in the British Isles may have little or no relevance to the impulses that drove the Swedes to cross the Baltic and, in due course, navigate their way down the Russian rivers to the Black Sea. The persistent Danish and Norwegian interest in the territories of the Frankish empire may not be illuminated by either explanation. Braving these difficulties - which are in truth insurmountable - we might suggest that the possible causes can be divided into two basic groups. The first consists of mainly abstract reasons that have a general applicability across the Scandinavian peninsula and the island territories of the Danes; the second deals with a set of more clearly defined causes, each with a specific and regional applicability. The divergences in the latter group are so great that I make no attempt to include possible reasons for the onset of a Swedish Viking Age here, saving those for a later chapter that deals with Viking activity east of the Baltic.

Adam of Bremen considered that the original cause of the Viking phenomenon was a simple one: poverty in the Scandinavian homelands. In De moribus et actis primorum normanniae ducum, Dudo of St-Quentin found a similarly straightforward explanation. In his résumé of the early life of Rollo, founder of the duchy, Dudo wrote of family quarrels over land and property at home that were resolved by ‘the drawing of lots according to ancient custom’. The losers in these lotteries were condemned to a life abroad, where ‘by fighting [they] can gain themselves countries where they can live in continual peace’. The drawing of lots as a way of solving urgent social problems is echoed in the Gotland Gutasaga, where a rapid increase in population and a subsequent famine were dealt with by a lottery as a result of which one in three families were obliged to leave the island with all their property.

Adam and Dudo both saw the movement of Viking bands about mainland Europe as what modern historians might identify as a late manifestation of the Age of Migrations. As the name implies, this was a period of intense restlessness that characterized mainland Europe for some 400 years, between 300 and 700. For reasons not yet properly understood but which it might seem natural to ascribe, as Adam and Dudo did, to poverty, shortage of land and natural disaster, successive waves of Germanic peoples began pouring across the Danube and moving westwards across Europe until they reached the frontiers of a crumbling Roman empire. The Ostrogoths, Visi goths, Alans, Burgundians, Langobards, Jutes, Angles, Saxons, Alemanni and Vandals were among them. These tribes rapidly brought about the fall of the empire in the west, adapted and adopted its political structures as they took over, and redrew the cultural and political map of Europe.

Roman intellectuals such as the first-century politician and historian Tacitus had long seen this as one likely fate for the empire. Tacitus’ ethnographic study De Origine et situ Germanorum, known as the Germania, was written partly to explain to his fellow citizens why the might of Rome had failed to conquer the Germanic tribes on their northern borders, despite their lack of Roman civilization and Roman discipline. The main reason was that Germanic males were naturally attracted to violence and enjoyed fighting. Leaders among them formed warbands and maintained the loyalty of their men by the practice of constant warfare. The commitment to their leader of members of such a warband or comitatus was personal: while the chieftain fought for victory, his men fought for him. Reward came in the form of feasts, entertainment and the proceeds of violence. Disdainful of trading and farming, such young men thought it ‘tame and stupid to acquire by the sweat of toil what they may win by their blood’.8 Within such a culture, ‘the bravest and most warlike do no work; they give over the management of the household, of the home, and of the land to the women, the old men, and the weaker members of the family, while they themselves remain in the most sluggish inactivity’. Arrogant idleness of the kind described by Tacitus is also a hallmark of some of the most notable heroes of the Icelandic sagas, men like Grettir the Strong and Egil Skallagrimsson, known in their youth as ‘coalbiters’ from their habit of idling away the days between adventures at home by the family longfire, irritably gnawing at lumps of coal, annoying themselves and annoying those around them. Tacitus’ description of the comitatus warband remains a valid account of the way Viking raiders organized themselves throughout the Viking Age, a loyalty-for-rewards structure that carried over even into the tenth and eleventh centuries and the establishment of rudimentary versions of Danish, Norwegian and Swedish monarchies.

The late Richard Fletcher offered, with due reservations, a coherent short narrative that linked together the main features of the case for a local crisis in early ninth-century Scandinavia that led so large a number of young men to depart their native lands in search of wealth and, eventually, respectability as the colonizers of new territories:

The diffusion of the use of iron in Scandinavia gradually made possible more intense agricultural exploitation. This in turn permitted demographic growth that would in time press upon the limited resources of the Scandinavian environment. Technical advances in shipbuilding, which would produce such masterpieces of strength and elegance as the Gokstad ship, opened the sea-ways of the North Sea and the Atlantic to Viking enterprise. The influx of silver bullion from the Islamic Middle East, well-attested archaeologically and attracted by trade in slaves, furs and timber with the distant lands of the caliphate in Iran, may have had far-reaching consequences for Scandinavian society. It provided capital for shipbuilding, weaponry and trading ventures. It drove a wedge between those who were its beneficiaries and the rest. An elite of wealth and status emerged, competitive and acquisitive, whose members attracted retinues of unruly young warriors on the make; and these men, in their turn, had to be rewarded. The emergence of stronger kings in Denmark and Norway, for reasons not unconnected with this new wealth, could make life at home difficult for these turbulent nobilities. It is to some such cluster of factors as these that we should attribute the beginnings of Viking age activity in western Europe.9

Inevitably, other interpretations of the material exist. By comparison with immediately preceding periods, the relative frequency of grave-finds from the Viking Age has been seen as evidence in support of a population explosion that began around 800. Yet the excavations at Forsandmoen in the Ryfylke district of Rogaland on the south-west coast of Norway which show that thriving settlements had existed there for over a thousand years between the Bronze Age and the Age of Migrations have failed to unearth a single grave from the period. It suggests that the incidence of graves found is not a reliable barometer of either the duration of a settlement or its intensity. Norwegian archaeologists have also registered a consistent decrease in the amount of iron produced in the forest and mountain regions of southern Norway during the early Viking period, and in the intensity of elk- and reindeer-trapping in the interior, and interpreted both as inconsistent with a theory that Norway was over-populated at the time.10 Another important component of the traditional theory is that the large number of Norwegian settlement names containing the element ‘-stadir’ (meaning ‘place’) originated in about 800, and that these too underscore a scenario in which a population explosion at about that time occurred with severe social consequences that included a Scandinavian diaspora. More recent interpretation of the archaeological data has shown, however, that these place-names should instead be associated with a wave of settlements that started in Norway as early as the fifth century.11 Ottar, a Norwegian merchant whom we shall meet again later, visited the Wessex court of Alfred the Great towards the end of the ninth century and told the king that he lived ‘furthest north of all the Norsemen’ and made his living by reindeer farming, whaling and exacting tributes from the nomadic Lapps. The discovery in 1981 of an enormous Viking Age farm at Borg, on the Lofoten Islands off the northern coast of Norway, confirms that the area north of the Arctic Circle was considered habitable by Viking Age families willing to look beyond conventional animal husbandry for their subsistence. The population density in the whole Scandinavian peninsula during the early Viking Age has been estimated at one to two people per square kilometre. The figure is an educated guess, but one that certainly does not support a theory of over-population.12

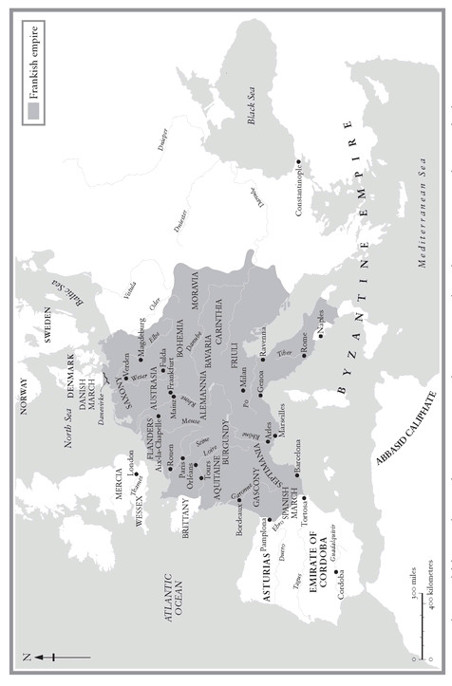

On the question of why raiding on northern Britain began in 793, and not fifty years earlier or forty years later, Norwegian historians and archaeologists have been increasingly attracted in recent years to an idea that looks outside Scandinavia for an explanation and takes into account the political tensions in northern Europe at the close of the eighth century.13 The three major political powers in the world at that time were the Byzantine empire in the east, which had survived the break-up of the Roman empire and its disappearance in the west; the Muslims, whose expansion during the years 660 to 830 under the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates had taken them eastward as far as Turkistan and Asia Minor to create an Islamic barrier between the northern and southern hemispheres; and the Franks, who had established themselves as the dominant tribe among the successor states after the fall of the Roman empire in the west. The Byzantine empire, with its capital Constantinople, was remote from the Scandinavian lands and would be more or less able to dictate the terms of its encounters with the Viking phenomenon. The Islamic expansion into Europe via the Iberian peninsula in the first half of the eighth century pushed European trade routes northwards, a development which increased trading opportunities for the Scandinavian lands and also created ideal conditions for piracy in the North Sea area. Of the three major powers it was the Franks who would be most profoundly involved with the Vikings.

By the middle of the eighth century most of Europe between the Elbe in the east and the Pyrenees in the west was under Merovingian Frankish - and Christian - control. In 751 Pippin became the first king of the dynasty known as the Carolingians. On his death in 768 he was succeeded jointly by his sons Charles and Carloman. With Carloman’s death in 771 Charles became sole ruler and presently set about the long series of expansionist gestures in the name of the Christian faith which characterized his reign and would gain him, within fifty years of his death, the appellation of Charlemagne, Charles the Great. His western-Europe territory was greater even than that of the Romans, who never ventured beyond the Rhine after the disaster of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in AD 9. Charlemagne took seriously the religious obligations imposed on him by his position as the most powerful ruler in western Christendom. He halted the Muslim expansion into Europe, drove the Arabs back across the Pyrenees, and established Frankish dominance in Spain and Gaul. The Lombards were driven from power in Italy, and the Slavs on the eastern border of his empire were compelled into tributary status. His authority, and that of the Christian Church, reached its limits at the Saxon marches in the north-east of the Frankish kingdom. Beyond lay the territories of the Danes and the Granii, the Augandzi, the Rugi, the Svear and Gautar in Sweden and the other more or less obscure Heathen tribes of the lower Scandinavian peninsula.

From about 772 onward Charlemagne’s chief preoccupation became the conversion to Christianity of the Saxons on his north-eastern border. In that year his forces crossed the rivers Ediel and the Demiel and destroyed Irmensul, the sacred wooden pillar or tree that was the Saxons’ most holy shrine, and probably their version of the ‘world-tree’ Yggdrasil of Scandinavian cosmology. The emperor’s determination to achieve his purpose is evident from an entry in the Royal Frankish Annals for 775:

The world beyond Seandinavia in 813. The 3 great political powers were the Frankish empire, the Byzantime empire, and the Muslim caliphates of the Ummayads of Cordoba and the Abbasids.

While the king spent the winter at the villa of Quierzy, he decided to attack the treacherous and treaty-breaking tribe of the Saxons and to persist in this war until they were either defeated and forced to accept the Christian religion or entirely exterminated.14

Another invasion of Saxon territory in 775 involved ‘severe battles, great and indescribable, raging with fire and sword’.15 In 779 Widukind, the Saxon leader, was defeated in battle at Bochult. Saxony was taken over and divided into missionary districts. Charlemagne himself conducted a number of mass baptisms, for the close identification of Christian missionary churches with Charlemagne’s military power was always made clear to the Saxons. A young English missionary, Lebuin, built a church at Deventer on the banks of the Ysel from which to lead his mission. When the Heathens burnt down his oratory, Lebuin made his way to the tribal gathering at Markelo and addressed the crowd:

Raising his voice, he cried: ‘Listen to me, listen. I am the messenger of Almighty God and to you Saxons I bring his command.’ Astonished at his words and at his unusual appearance, a hush fell upon the assembly. The man of God then followed up his announcement with these words: ‘The God of heaven and Ruler of the world and His Son, Jesus Christ, commands me to tell you that if you are willing to be and to do what His servants tell you He will confer benefits upon you such as you have never heard of before.’ Then he added: ‘As you have never had a king over you before this time, so no king will prevail against you and subject you to his domination. But if you are unwilling to accept God’s commands, a king has been prepared nearby who will invade your lands, spoil and lay them waste and sap away your strength in war; he will lead you into exile, deprive you of your inheritance, slay you with the sword, and hand over your possessions to whom he has a mind: and afterwards you will be slaves both to him and his successors.’16

The ‘nearby king’, of course, was Charlemagne. Once they had recovered from their surprise the Saxons seized Lebuin and would have stoned him to death had not an elder intervened to save his life. In 782 the Saxons rebelled again and defeated the Franks in the Süntel hills. Charlemagne’s response was the infamous massacre of Verden on the banks of the river Aller, just south of the neck of the Jutland peninsula. As many as 4,500 unarmed Saxon captives were forcibly baptized into the Church and then executed.17Even this failed to end Saxon resistance and had to be followed up by a programme of transportations in 794 in which about 7,000 of them were forcibly resettled. Two further campaigns of forcible resettlement followed, in 797 and in 798. A final insurrection was put down in 804 and Einhard the Monk, Charlemagne’s biographer, articulated the fate of the defeated tribe. The Saxons were to ‘give up their devil worship and the malpractices inherited from their forefathers; and then, once they had adopted the sacraments of the Christian faith and religion, they were to be united with the Franks and become one people with them’.18 Charlemagne’s capitulary for Saxons, De Partibus Saxoniæ, operative by the mid-780s, listed the punishments for those who tried to reject the imposition of Christian religious culture:19 death for eating meat during Lent; death for the cremating of the dead in accordance with Heathen rites; death for any ‘of the race of the Saxons hereafter, concealed among them, [who] shall have wished to hide himself unbaptized, and shall have scorned to come to baptism, and shall have wished to remain a Heathen’. Heathens were defined as less than fully human so that, under contemporary Frankish canon law, no penance was payable for the killing of one.20By way of comparison, under the 695 law code of the Kentish King Wihtred, Christians caught ‘sacrificing to devils’ were punishable merely by fines and the confiscation of property.21

Charlemagne and his missionaries set the terms of the encounters between Christians and Heathens, destroying the religious sanctuaries and cultural institutions of those who refused to embrace Christianity exclusively, and the Heathens saw no reason not to respond in kind. When Saxons attacked and burned Christian churches, an element of reciprocated cultural hostility lay behind their attacks. In the Royal Frankish Annals account of the attack on a church at Fritzlar in 773 the sole aim of the Heathens was to set fire to the church:

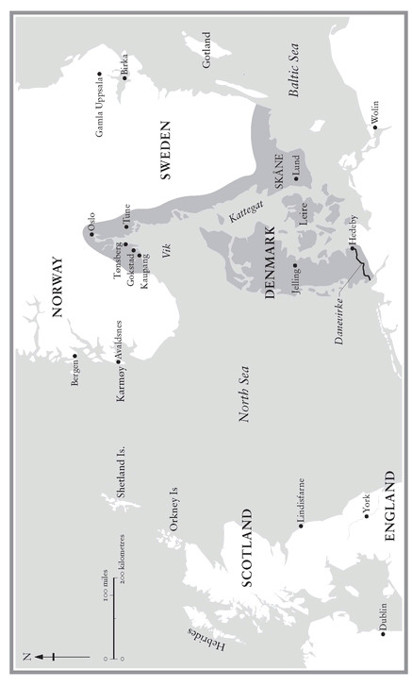

The first Viking raids on north-eastern Britain were launched from the Norwegian west coast. The shaded area shows Denmark and the sphere of influence of Danish Kings in about 800.

The Saxons began to attack this church with great determination, trying one way or another to burn it. While this was going on, there appeared to some Christians in the castle and also to some Heathens in the army two young men on white horses who protected the church from fire. Because of them the pagans could not set the church on fire or damage it, either inside or outside. Terror-stricken by the intervention of divine might they turned to flight, although nobody pursued them. Afterwards one of the Saxons was found dead beside the church. He was squatting on the ground and holding tinder and wood in his hands as if he had meant to blow on his fuel and set the church on fire.22

Charlemagne’s vast empire ran from the Ebro in Spain to the Elbe in northern Germany, and the line between it and the Saxons’ small pocket of territory in the north-east corner of Europe passed through more or less open country. Once Charlemagne had made up his mind to crush his neighbours there could have been, in Einhard’s confident phrase, ‘only one possible outcome’.23 Even so, the great English historian Edward Gibbon expressed surprise at the degree of effort the emperor put into the war, reflecting on ‘three-and-thirty campaigns laboriously consumed in the woods and morasses of Germany’ which would have brought easier and greater glory had they been directed against the Greeks in Italy, and a further reduction in Muslim power in Spain. To Gibbon, the political significance of Charles’s treatment of the Saxons was clear:

The subjugation of Germany withdrew the veil which had so long concealed the continent or islands of Scandinavia from the knowledge of Europe, and awakened the torpid courage of their barbarous natives. The fiercest of the Saxon idolaters escaped from the Christian tyrant to their brethren of the North; the Ocean and the Mediterranean were covered with their piratical fleets; and Charlemagne beheld with a sigh the destructive progress of the Normans, who, in less than seventy years, precipitated the fall of his race and monarchy.24

Gibbon was echoed in 1920 by the English novelist and man-of-letters H. G. Wells in his widely read The Outline of History:

Most of our information about these wars and invasions of the Pagan Vikings is derived from Christian sources, and so we have abundant information of the massacres and atrocities of their raids and very little about the cruelties inflicted upon their pagan brethren, the Saxons, at the hands of Charlemagne. Their animus against the cross and against monks and nuns was extreme. They delighted in the burning of monasteries and nunneries and the slaughter of their inmates.25

Lucien Musset, the greatest French scholar of the Viking Age in the twentieth century, is another who insisted that the violence that is its most outstanding characteristic must have had its origins in a cultural and religious conflict of the most dramatic sort.26

Several times in the course of his doomed campaign of resistance, Widukind had sought refuge across the border with his brother-in-law Sigfrid, a Danish king. His tales can have left Sigrid in no doubt as to the passion with which his powerful Christian neighbour in the south lived out the missionary imperative of Christianity. News of the Verden massacre must have travelled like a shock-wave through Sigfrid’s territory, crossing the waters of the Kattegat and the Vik and on into the Scandinavian peninsula, arousing fear, fury and hostility towards both Charlemagne and Christianity. An incident that took place in 789 on the south coast of England at Portland, involving ‘the first ships of Danish men which came to the land of the English’, may well reflect the tensions aroused by this incident.27 The chronicler Æthelweard provides a scene-setting description of the incident, with people ‘spread over their fields and making furrows in the grimy earth in serene tranquillity’ when the ships arrived. The king’s reeve, a man named Beaduheard, rode to the harbour and confronted the sailors, admonishing them ‘in an authoritative manner’ before ordering them to be taken to ‘the royal town’. The men, who had identified themselves as natives of ‘Hörthaland’, the modern Hordaland on the west coast of Norway, must have refused, for a fight broke out and Beaduheard and his men were killed. With no mention of subsequent plundering or attacks on churches or monasteries it looks like a case of fatal mistrust, routine perhaps, were it not for the raid on the monastery at Lindisfarne four years later to which it now seems a prelude. Perhaps the men were afraid they might be forcibly baptized and then executed. The Danes were certainly on the Church’s list of peoples to be converted. Bede mentioned them, along with the Frisians, the Rugini, the Huns, the Old Saxons and the Boructvari, among a number of Germanic peoples still observing pagan rites in the early eighth century.28 In about 710, during the time of King Ongendus, a fearsome Heathen ‘more savage than any beast and harder than stone’, Bede’s contemporary, St Willibrord, carried out his mission among the Danes and returned to Utrecht with thirty boys whom he intended to instruct in Christianity. Clearly nothing had come of this, for in the year of the Portland raid Alcuin had written to a friend, proselytizing among the Saxons, ‘Tell me, is there any hope of our converting the Danes?’29

Our pluralistic twenty-first century tries to encourage respect for the cultures of others and an acceptance of them on their own terms. The position would have baffled men like Bede and Alcuin, effortlessly certain of their right to impose the new and superior values of one culture upon another perceived as inferior and backward. We see Heathen ninth-century Scandinavians not as the horde of savages they were to these early churchmen but as a people who had evolved a social and spiritual culture of their own. Certainly it was very different from that of the Christians, but it was their own and we must assume they were content with it.30 The Norwegian archaeologist Bjørn Myhre has suggested that for a period of perhaps three or four hundred years there had been a relatively stable North Sea community of peoples enjoying normally peaceful contact across the water with each other as traders, in technological and artistic exchange, in marriage and in the fostering of each other’s children.31 Alcuin’s letter to the Northumbrian King Ethelred, quoted at the beginning of this chapter, is evidence for this kind of contact. So too are the grave-goods and shield and helmet from the East Anglian Sutton Hoo ship-burial from the middle years of the seventh century, which bear striking stylistic resemblances to Swedish artefacts of the same period found in royal graves at Vendel and Valsgärde. Ironically, this posited stability may in part have been due to the emergence of the Merovingian Franks as the dominant power in mainland Europe during the sixth and seventh centuries, one result of which had been to encourage trade around the North Sea and the development of a string of coastal trading towns like Dorestad at the mouth of the Rhine, Hamwic on the site of present-day Southampton, London by the Thames, Ribe on the west coast of South Jutland from about 700 and Kaupang in the Norwegian Vestfold a few years later.

As the degree of tension caused by Charlemagne’s activities grew more marked, so too, in accordance with a familiar anthropological response to outside threat, did the intensity with which the Scandinavians began to mark their artefacts as a way of asserting their cultural identity. Burial practices, personal ornamentation like brooches, clothing styles and the design of houses all show, on this interpretation, a heightened degree of intensity in ethnic self-identification. 32 The threat may even have affected Viking Age poetry. As we noted earlier, many scholars believe that the Viking Age’s greatest spiritual monument, ‘The Seeress’s Prophecy’, was composed comparatively late in the history of northern Heathendom as a direct response to the threat of militant, expansionist Christianity and the dramatic and seductive Judaic creation myths of the Bible.33 The local Scandinavian cultures that felt the first stirrings of this threat were neither compact nor centralized enough to organize themselves into anything like a structure that could have mounted a military campaign against Frankish Christendom. A more feasible goal, closer at hand, easier of reach, undefended and, in the parlance of modern terrorist warfare, ‘a soft target’, was the monastery at Lindisfarne. In Alcuin’s phrase, it was ‘a place more sacred than any in Britain’. With an indifference to the humanity of their Christian victims as complete as that of Charlemagne’s towards the Saxons, a psychopathic rage directed at the Christian ‘other’ was unleashed, expressing itself in infantile orgies of transgressive behaviour that offered the same satis factions whether the taboos transgressed were their own or those of their victims.34 Simeon of Durham tells us that monks were deliberately drowned in the sea by the raiders: perhaps some travesty of baptism was intended. They dug up the altars, presumably because someone had revealed to them, under torture, that some of the monastery’s greatest treasures lay buried there - but aware, too, of a blasphemous offence to their victims that was every bit as great as that suffered by the Saxon Heathens at the destruction of Irmensul. A feature of the raiding and church-burning that ensued was the Vikings’ penchant for cutting up stolen items, like Bible clasps and crosses, and reshaping them into items of personal ornamentation. ‘Ranvaik owns this box’, its new owner had inscribed in runes on a beautiful, house-shaped box found in Norway in the seventeenth century. Graffiti depicting the prows of longships had been carved on its base. Made in Scotland towards the end of the eighth century, its original purpose had been to house the bones of a Christian saint. Useful enough for Ranvaik no doubt, but also an active expression of cultural disrespect. 35

Non-literate Viking culture has nothing to say to us on this difficult subject, but from the time the Vikings first came to the attention of the annalists in England, the view of their victims was insistently that they were engaged in an ongoing religious war. Though they were sometimes their place of origin, with ‘Danes’ serving as a generic term for all Scandinavians, sometimes ‘foreigners’ and sometimes ‘flotman’, ‘sæman’, ‘sceigdman’ and ‘æscman’ - all terms referring to their being seaborne raiders - with overwhelming frequency the Vikings were referred to in terms of their religion.36 One hundred years after the first Lindisfarne raid, the Welsh bishop Asser, in his biography of Alfred the Great, continued to refer to those much larger bands of Scandinavian aggressors who had by then established themselves along the eastern seaboard of England as ‘the pagans’ (pagani), and to their Anglo-Saxon victims as ‘the Christians’ (christiani). Alcuin had sensed at once the real consequences of the 793 raid. ‘Who does not fear this?’ he had asked in his letter to Ethelred of Northumbria. ‘Who does not lament this as if his country were captured?’