This Edwardian Welsh Guards poster simply stipulated that eligibility for membership of the regiment depended on recruits either having a Welsh parent ‘on one side’ at least, being domiciled in Wales or Monmouth or having a Welsh surname!

Collectors of historic printed documents are prospecting along the final remaining frontier of available, authentic wartime items. Traditionally less-expensive than other more familiar items like badges and uniforms, both vigorously traded for years, lots of authentic printed ephemera remains undiscovered. Furthermore, although high-end militaria has long been subject to fakery, printed items are more difficult to forge convincingly. But, be warned, with individual wartime posters now commanding as much as £1,000, the stakes have been raised. This undiscovered country isn’t going to remain fruitful for long.

Although long overlooked in favour of more substantial pieces of military clothing and equipment – including that perennial favourite, Nazi regalia – ephemeral printed items are now being collected with fervour. Not before time in my opinion, because these printed pieces often provide the enthusiast with a much better picture of the reality of life during wartime, be that from the point of view of the front-line soldier or the civilian on the home front. Vintage paperwork adds context to individual items like badges and helmets and helps to explain what people had to endure when embroiled in the reality of total war.

Turn of the century postcard showing the Devonshire Regiment still resplendent in scarlet tunics.

One reason for the new-found popularity of previously disregarded items is simply because their availability provides a pleasant surprise – they were never expected to have a long life. On the contrary, they were designed to have only temporary, ephemeral, appeal. Consequently most of these items were not saved; they were simply disposed of instead. Therefore they have, by default, become quite rare.

Furthermore, given that the big ticket items that have been the traditional province of serious collectors for generations: military dress, regalia and certain medals and unit badges, are now regularly counterfeit, collectors are better off casting their net wider. Printed ephemera, though of less intrinsic value, is far more difficult to fake convincingly. Surprisingly, it’s far easier to make a copy of a badge, a ‘re-strike’, adding the odd blemish here and some tarnish there, than it is to copy a piece of 1940s heat-set lithographic printed material and achieve not only accurate colour reproduction but the texture and distinctively musty smell of vintage paper.

The dictionary definition of ephemera is ‘things of only short-lived relevance’, meaning that most printed items were never imbued with much value when they first appeared. Although mass-produced, often in the hundreds of thousands, relatively few original items survive today. And, as we all know, rarity is as attractive to collectors as shiny objects are to magpies. So, after long taken for granted, the myriad documents each belligerent government produced in support of their nation’s war effort, are at last achieving high prices on the collectors’ market.

Trench warfare didn’t only spell the end of military pomp and regalia it saw the introduction of mechanised warfare as depicted on this naive French postcard.

This book aims to explore the realm of twentieth-century printed ephemera and provide details for the collector about what to look out for, who produced what and why they did so and, most importantly, where to find such collectables and what to pay for them.

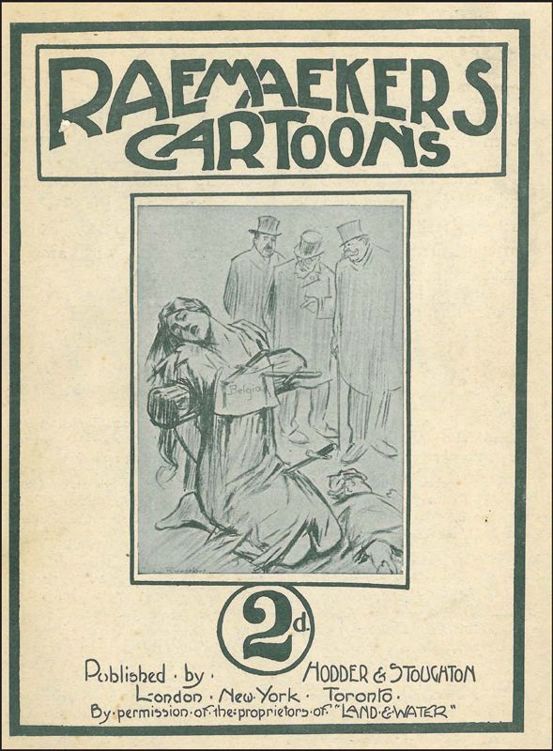

At the outbreak of the Great War, Britain’s authorities first began to put their own slant on why the nation had become embroiled in the conflict and what role the government was adopting, which it expected its electorate to follow. When the new War Propaganda Bureau began work on 2 September 1914, its work was so secret that it was not until 1935 that its activities were revealed to the public. Several prominent writers agreed to write pamphlets and books that would promote the government’s point of view and these were printed and published by such well-known publishers as Hodder & Stoughton, Methuen, Oxford University Press, John Murray, Macmillan and Thomas Nelson. In total, the War Propaganda Bureau went on to publish over 1,160 pamphlets during the war.

The German government placed a reward of 12,000 guilders, dead or alive, on Dutch artist Louis Raemaekers’ head. Raemaekers’ graphic cartoons depicted the German military in Belgium as barbarians and Kaiser Vilhelm II as an ally of Satan. The Germans also accused Raemaekers of ‘endangering Dutch neutrality’.

In Britain, the build-up to the Second World War was characterised by the official appeasement of Hitler’s expansionist behaviour. The Führer reoccupied the Rhineland, entered Austria, proclaiming union (Anschluss) with that sovereign country, and even dismembered Czechoslovakia following his acquisition of the Sudetenland, without the British government doing much more than expressing its displeasure. At the time government propaganda at home concentrated on informing Britain’s civilian population of the dangers of modern war, which despite their confident expressions of peace in our time, they knew was a foregone conclusion.

The fear of chemical attack from enemy air fleets – ‘the bomber will always get through’ – and the vulnerability of modern cities to high explosives and incendiaries encouraged the development of volunteer Air Raid Precaution (ARP) services and the production of numerous leaflets informing householders about how to survive such an eventuality. Fear of aerial attack, and in particular of gas being sown by enemy bombers, presented a terrifying prospect which films like Korda’s 1936 epic Things to Come, based on H.G. Wells’ prophetic vision, did little to allay. After the war, Harold Macmillan, a Cabinet minister during the Second World War who became Prime Minister in 1957, wrote: ‘We thought of air warfare in 1938 rather as people think of nuclear warfare today.’

Amazingly, as an item in this book proves, there were many quite liberally minded people who thought that Hitler’s decision to incorporate the largely German-speaking Sudeten region of Czechoslovakia into the Third Reich, which triggered the Munich Crisis in 1938, was not an unreasonable ambition. But other than the occasional vociferous outburst from politicians like Winston Churchill or the gradually shifting views of previously pro-Hitler press barons like Lord Beaverbrook and Lord Rothermere, there was little official pro-war information in circulation. Despite this, in 1935 the Daily Mail’s Rothermere presented the prototype Bristol Blenheim aircraft, Britain First, as a gift to the nation and a vital addition to the RAF’s bomber fleet.

Notwithstanding Britain’s desire to stay out of another European war, at least until enough Spitfires had been built, the 1938 Czechoslovakian crisis saw a dramatic increase in the amount of leaflets distributed among its citizens which encouraged them to learn about and prepare for the reality of enemy aerial bombardment.

Hitler’s invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 was the spark which ignited the long-feared conflict. Britain’s declaration of war on 3 September saw a distinct change in the tone and manner of official government pronouncements. Now the gloves were off and printing presses worked overtime extolling citizens to do their bit, stay firm and go about their daily life with the traditional stoicism of John Bull.

Today, I guess the most famous piece of government propaganda from this period is the iconic ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ poster created by the new Ministry of Information (MOI). Ironically, although it was printed and ready for distribution when the war started, this poster was only to be employed in the event of an invasion of Britain by Germany. As this never happened, the poster was never widely seen by the public.

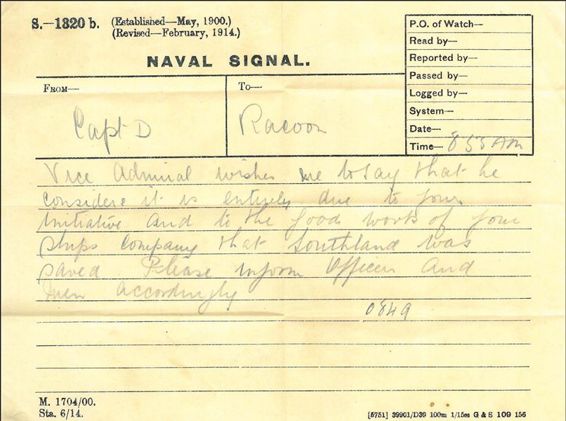

Collectors of wartime ephemera have a wealth of material to look out for. This naval signal from the First World War is particularly interesting. Sent from the Vice Admiral, it congratulates the efforts of the ship’s company of HMS Racoon for their part in saving the liner HMT Southland after it was torpedoed in the Aegean Sea by a German submarine in 1915.

At one point the German spring offensive of 1918 swept all before it, causing panic not just in France but further afield. Towns along the northeast coast of England had been subject to German naval attack early in the war and some feared an all-out maritime invasion. Taking no chances, the good fathers of Grimbsy prepared this poster advising their citizens about what to do if the worst came to the worst.

It was long believed that most of the ‘Keep Calm’ posters were destroyed and reduced to a pulp at the end of the war in 1945. However, nearly sixty years later, a bookseller from Barter Books stumbled across a copy hidden among a pile of dusty old books bought from an auction. A small number also remain in The National Archives and the Imperial War Museum in London, and a further fifteen were discovered through the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow programme, having been given to Moragh Turnbull, from Cupar, Fife, by her father William, who served as a member of the Royal Observer Corps.

The seemingly ubiquitous ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ poster has probably become one of the most famous publications associated with the British home front in the Second World War. However, as readers of this book will discover, it was seen by hardly anyone during the war and only became famous after it was rediscovered in 2000 by Stuart Manley of Barter Books in Alnwick, Northumberland!

Vintage newspapers can be secured for relatively small sums but need careful conservation (see Chapter 7). This 9 April 1940 edition of the Londodeals with the ill-fated Norwegian campaign. Ironically, like Gallipoli in the First World War, an idea of Churchill’s but one which saw the First Lord of the Admiralty accede to the premiership while Neville Chamberlain paid the price for failure and lost his job.

And this is why ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ has become possibly the most famous government instruction originating from the Second World War!

The MOI was dissolved in March 1946, with its residual functions passed to the newly established Central Office of Information (COI), a centralised organisation supporting officialdom with a range of specialist information services. Fortunately today, much of what the MOI and HMSO (His Majesty’s Stationery Office – responsible for printing, marketing and the public distribution of numerous illustrated publications describing the progress of particular campaigns and the activities of the civilian workers at home) produced survives and much of it is shown in this book. It is more collectable than ever before.

This book includes far more than official British government publications. To paint an accurate picture of twentieth-century wartime, we need to consider the myriad other items that supported the war efforts at the front and at home. Therefore, examples of the kind of things that entertained and informed both the young and the old during the dark days of war are also included. Items such as postcards, song sheets, periodicals, official and unofficial publications, such as the famous Wipers Times from the 1914–18 conflict, feature throughout the pages of this book. I hope the combination of illustrations and narrative fact will appeal not only to the collector but also to those interested in the social history of twentieth-century warfare and the effect it had on ordinary men, women, boys and girls who had the misfortune to live throughout it.

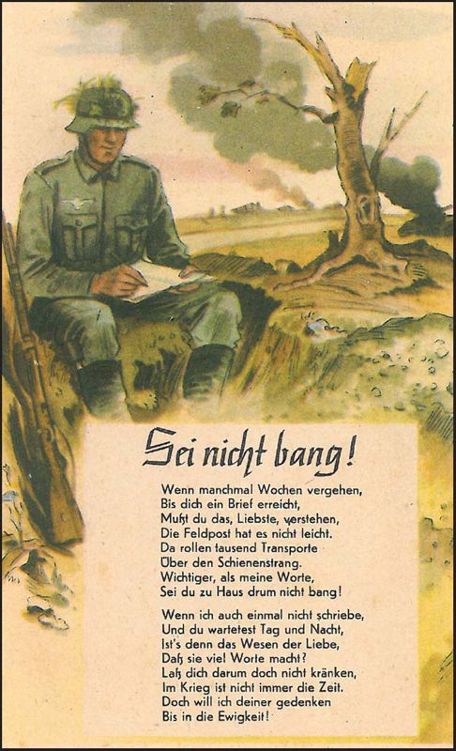

Postcards were a useful way fighting men of all nations could keep in touch with loved ones at home. This very collectable German example stresses the importance of a pause in the shooting so troops could catch up on their correspondence from home.

The Daily Mirror reported Hitler’s death on 2 May 1945 and stated that Admiral Karl Dönitz would succeed him as Führer.

Safe-conduct pass signed by Dwight D. Eisenhower, then Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force during Operation Torch in North Africa. When presented by a surrendering Axis soldier, the supplicant was guaranteed a welcome and lenient reception.

I am grateful to the following for the assistance in preparing this book: Mirella Aslar, Zaki Jamal, Jayne Joyce and Stuart Manley and Jim Walsh at Barter Books.

Arthur Ward

Pulborough, West Sussex

September 2014