CHAPTER 1

Towards the end of the English Civil War, the London-based petitioner movement known as the Levellers, comprising soldier ‘Agitators’ of the parliamentarian New Model Army and a number of prominent politicians, produced a draft written constitution under the title of ‘Agreements of the People’. Their efforts were the catalyst for a series of famous debates in the autumn of 1647 held in St Mary’s Church, Putney, to decide the prospective settlement of the nation, the right of all men to have the vote and, especially, about whether Charles I had any future as the nation’s king. Charles was tried at Westminster Hall in January 1649, and after it was decided that he had ‘traitorously and maliciously levied war against the present Parliament and the people therein represented’ he was executed. So the monarch’s fate had been decided.

However, despite their best efforts the Levellers did little better and with the king out of the picture absolute power now resided with the army and in particular Oliver Cromwell, the man who was soon to become ‘The Lord Protector’. By 1650 they were no longer a serious threat to the established order and the powerful remained in power. But, despite this state of affairs, part of the legacy of this tumultuous period is that from the late seventeenth century Britain’s authorities could no longer assume the tacit approval of the body politic for forthcoming military adventures or expeditions. From now on the people had to be persuaded that going to war was an expedient option and that the cost and inevitable suffering incurred was a price worth paying.

Satirical postcard showing the difference between the Kaiser’s apparent self-image and how others really saw him.

A tangible method used to communicate the early official propaganda used to persuade the people of the government’s wisdom were handbills, sketches and cartoons. At first these were distributed within news-pamphlets and after the Restoration of the monarchy appeared in publications such as the London Gazette (first published on 16 November 1665 as the Oxford Gazette), and from 1702 of the Daily Courant, London’s first daily newspaper (there were twelve London newspapers and twenty-four provincial papers by the 1720s).

A curious side-effect of this dissemination was the emergence of the cult of personality. As readers were provided with information about the battles their armies were fighting, they were also given details about the commanders who led the troops. Consequently, Marlborough, victor at the Battles of Blenheim in 1704 and Ramillies in 1706, which drove the French forces from Germany and the Netherlands during the War of the Spanish Succession, and later Wolfe, who stormed the heights below the Plains of Abraham during the Battle of Quebec during the Seven Years War and died doing so, became household names and not distant, out-of-reach, aristocrats.

‘Women of Britain Say – Go!’ by E. V. Kealey. A mother and her children watch from the window of their home as some soldiers march off to war. It was originally published by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, London.

Patriotic German postcard from the early part of the First World War. It shows a young girl telling the Kaiser that she wants to dedicate a flower to him.

Another side-effect was the emergence of satirical counter arguments which questioned official policy and ridiculed the attitudes and behaviour of many of the previously exalted worthies.

William Hogarth and other British satirists gave vent to the frustrations and incredulities of a more questioning population during this period. Although they were subsequently more famous for their novels, writers, such as Daniel Defoe, who, in February 1704, began his weekly, the Review – a forerunner of both the Tattler and the Spectator, and Jonathan Swift, the most influential contributor between November 1710 and June 1711 of the Examiner, which started life in 1710 as the chief Conservative political mouthpiece, both contributed to a growing climate of cynical observation. What electorate there was at this time still had to be convinced that their country was on the side of right.

The Seven Years War had seen the age-old colonial struggle between the British and French empires spread across two continents, extending from Europe to North America, where the westward expansion of the British colonies conflicted with the interests of France and ultimately melded with the grievances of American colonists that led to the American Revolution. Benjamin Franklin drew and published the first political cartoon in the colonies in 1747. His woodcut leaflet Plain Truth, depicting a kneeling man praying to Hercules who is sitting in the cloud, an allegory of ‘Heaven helps him who helps himself’, told the American colonists to defend themselves against the Indians without British help. Franklin’s subsequent 1754 cartoon of a snake chopped into pieces, advised the colonies to ‘join or die’, to unite against their common foe, further encouraging sedition.

When, in the spring of 1798, twenty years after the end of the American War of Independence and the loss of the colonies, General Bonaparte’s ‘Army of England’ massed along the Channel coast of France, the House of Commons again called the country to arms. Anti-Napoleon propaganda abounded in Britain and caricatures by the names of James Gillray and George Cruikshank flooded not only the British market but influenced German and French anti-Napoleonic sentiment in occupied territories as well. In Britain such satire not only aroused patriotism it raised awareness against possible French invasion, and drove enrolment in the army or navy and many towns raised volunteer groups of infantry and cavalry. This invasion crisis ended with Nelson’s victory over the French Fleet, graphically depicted by Gillray who published caricatures showing John Bull eating the French ships, and a badly punished and bruised Napoleon, with a wound on his chest, labelled Nelson.

In July 1853 Tsar Nicholas’s occupation of territories in the Crimea previously controlled by Turkey’s Ottoman Empire encouraged Britain and France to declare war in an attempt to halt such Russian expansionism. The Crimean War was one of the first wars to be documented extensively in written reports and photographs, most notably by William Howard Russell, who wrote for The Times newspaper, and the photographer, Roger Fenton, whose images brought the reality of war into the living rooms of ordinary civilians. In his reports of the battles and especially of the Siege of Sevastopol, Russell said ‘Lord Raglan is utterly incompetent to lead an army’ – this was the first time such divisive comment about Britain’s military commanders had appeared in the press. Revealing the sufferings of the British Army during the winter of 1854, his accounts even upset Queen Victoria who described Russell’s writings as ‘infamous attacks against the army which have disgraced our newspapers’. Lord Raglan complained that Russell had revealed military information potentially useful to the enemy. But coupled with the observations of Mary Seacole and Florence Nightingale, the correspondent’s reports that British soldiers were dying of cholera and malaria motivated a public outcry and led to resignations in government.

This revolution in the ability of newspapermen and social commentators to file up-to-the-minute reports was largely facilitated by the electric telegraph and was a foretaste of modern war. It is also an early example of how the media could influence public opinion in the way TV showing images of body bags of dead GIs being unloaded from cargo aircraft returning from Vietnam in the late 1960s encouraged the United States to pull out of that costly war.

By the time of the South African, or Second Boer War, which began in October 1899 and continued until May 1902, developments in communications technology had further improved so that newspapers were able to keep their readership in Britain up to date with the twists and turns of the bloody conflict taking place 5,500 miles away. British householders read of the underhand hit and run tactics of the Boer fighters of the semi-independent South African Republic (Transvaal) and the initially, at least, scarlet-clad ranks of British soldiers. Soon Tommy Atkins adopted many of the methods of his adversary and readers discovered that British troops had swapped their high-visibility tunics for more discreet khaki uniforms and had gradually became better equipped to deny the rebellious claims of their volunteer enemy. Anxious Britons greedily consumed any news from South Africa, and news of the relief of Mafeking on 18 May 1900 was so deliriously received it encouraged street parties and public celebrations the likes of which had never before been seen.

Britain and France were confident that the Entente Cordiale agreements they’d signed on 8 April 1904 would see them safely through the war.

‘To Willie with Compliments – Our grand artillerymen like to address a shell before they fire it. This shell, being one of the biggest size, is addressed to the biggest Hun.’

As the tide of the war gradually favoured the British, thousands of Boer families were forced into concentration camps, leading to the death of more than 25,000 Boer women and children as well as 20,000 native Africans. The biggest scandal of the war, the camps began to influence British public opinion; the Manchester Guardian blamed the deaths on British brutality while pro-government newspapers such as The Times argued that they were caused by poor hygiene on the part of the Boers. Altogether nearly 30,000 whites died in the concentration camps, more than twice the number of fighting men, on both sides, who died in battle.

In 1906 the Boers were granted self rule and in 1910 the Union of South Africa was formed. Ironically, many Boer generals fought alongside their British comrades during the Great War and it was during this conflict that Britain used every aspect of modern communications to get its message across both in terms of inspiring new recruits to the armed services but also to reassure the public at home that their men were fighting the good fight on the side of might and right. Interestingly, like it had done successfully during the South African War, when it demeaned and denigrated the rebels and families of the breakaway provinces, accusing the Boers of brutish and underhand methods and their women folk of ignorance and stupidity, Britain also placed significant emphasis on atrocity propaganda as a way of mobilising public opinion against Germany during the First World War. The ‘Hun’ was depicted as a beast, a despoiler of women and a murderer of children.

Before the Unites States joined the fray the combined armies facing the Germans and Austro-Hungarians proved a not inconsiderable obstacle to the Kaiser’s ambitions.

However, although a well-established press stood by as a ready vehicle to communicate such government propaganda and the new picture palaces could project newsreels to eager audiences sitting slack jawed as they watched footage of our boys at the front, at the war’s outbreak Britain lacked any official propaganda agencies. Britain’s discovery that, on the other hand, Germany had a very active one and was vigorously employing it to communicate its side of the story to neutral countries, the most important of which was the United States of America, encouraged the urgent development of a specialist department, the War Propaganda Bureau, which though operating from a new home, Wellington House, a former insurance office located in Buckingham Gate, London, was under the direct supervision of the Foreign Office.

In August 1914 David Lloyd George, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, was given the task of establishing the new organisation and he appointed the writer and fellow Liberal MP Charles Masterman to head it. In turn Masterman invited twenty-five leading British authors to Wellington House to discuss ways of best promoting the country’s interests during the war. These included such luminaries as William Archer, Arthur Conan Doyle, Arnold Bennett, John Masefield, Ford Madox Ford, G.K. Chesterton, Henry Newbolt, John Galsworthy, Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, Gilbert Parker, G.M. Trevelyan and H.G. Wells. Painters of the stature of Francis Dodd and Paul Nash were also asked to work with the Bureau, the main objective of which was to encourage the United States to enter the war on the British and French side. As a consequence, exhibitions of paintings and lecture tours were organised in the United States establishing unique links between aesthetes, writers and other influential creative minds from either sides of the Atlantic. Drawing on an extensive network of the most important and influential figures in the London arts scene, Masterman devised the most comprehensive arts patronage schemes ever to be supported in the country.

Full of highly emotional drawings created by the Dutch illustrator Louis Raemaekers, early in 1915 the Bureau produced its first significant publication, the Report on Alleged German Outrages. Documenting atrocities both actually and allegedly committed by the German Army against Belgian civilians, this pamphlet achieved exactly what was intended and changed British attitudes towards Germans and Germany. No longer was Germany the culturally sophisticated home of Beethoven and Mozart, it was now the breeding ground of barbarians.

Masterman was also the prime mover behind Nelson’s History of the War and from February 1915 this monthly magazine was published in twenty-three editions. Author John Buchan, of The Thirty-Nine Steps fame, headed the production and it was printed by his publisher, Thomas Nelson. Incidentally, Buchan was given the rank of Second Lieutenant in the Intelligence Corps and provided with the necessary documents to write the work.

As intended, Raemaekers’ skilfully drawn cartoons conjured precisely the emotions of hatred against the supposedly barbaric enemy.

After January 1916 the Bureau’s activities were subsumed under the office of the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. After the success of the initial trials with artists like Dodd and his brother-in-law, artist Muirhead Bone, in 1917 arrangements were made to send other artists to France. Ill-health forced one of them, society painter John Lavery, to stay in the British Isles and paint pictures of the home front but, despite this, he was nearly killed by a Zeppelin during a bombing raid!

Alongside Wellington House, two other organisations were established by the government to deal with propaganda. The first was the Neutral Press Committee, which was given the task of supplying the press of neutral countries with information relating to the war and was headed by G.H. Mair, former assistant editor of the Daily Chronicle. The second was the Foreign Office New Department, which served as the source for the foreign press of all official statements concerning British foreign policy.

In February 1917 the government established a Department of Information and John Buchan was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and put in charge of it. Masterman, however, retained responsibility for books, pamphlets, photographs and war art, while T.L. Gilmour, the first secretary of the National Savings Committee, was charged with encouraging patriotic citizens to buy war bonds, was responsible for telegraph communications, radio, newspapers, magazines and the cinema.

In early 1918 it was decided that a senior government figure should take over responsibility for propaganda and on 4 March Lord Beaverbrook, owner of the Daily Express newspaper, was made Minister of Information. Masterman was subsequently placed in a subordinate position beneath him as Director of Publications, and John Buchan became Director of Intelligence. Lord Northcliffe, owner of The Times and the Daily Mail, was put in charge of propaganda aimed at enemy nations, while Robert Donald, editor of the Daily Chronicle, was made director of propaganda aimed at neutral nations. In February 1918, following the announcement of this reorganisation, Lloyd George was accused of creating this new system only to gain control over Fleet Street’s leading figures.

In my opinion Ludwig Hohlwein is the greatest of all poster artists. This superb example is designed to raise funds in aid of German prisoners of war and civil detainees.

Propaganda was not the government’s only concern of course. Getting the message across was one thing. Preventing certain information from circulating, censorship, was quite another and just as important. Little more than a week before hostilities broke out in 1914, Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, announced in the House of Commons the setting up of a press bureau with the dual task of censoring press reports and of issuing to the press what he said would be ‘all the information relating to the war which any of the Departments of State think it right to issue’. Throughout the war the various provisions of the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) specified the matters for which publication was an offence. Mostly these related to the number and disposition of troops and any operational details which might jeopardise future strategy.

Feeding Britain’s new propaganda machinery and those similar departments in each of the other belligerents was an army of some of the greatest artists and illustrators in the world.

Perhaps one of the earliest and most famous images of the Great War is Alfred Leete’s poster of Kitchener – ‘Your country needs you!’. Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener had won fame in 1898 for winning the Battle of Omdurman and securing control of the Sudan, becoming ‘Lord Kitchener of Khartoum’. As Army Chief-of-Staff and later Commander-in-Chief in the Second Boer War he had played a key role in suppressing Boer forces. At the start of the First World War, Lord Kitchener became Secretary of State for War, a Cabinet minister, and immediately went about organising the largest volunteer army that Britain had ever raised.

‘Vive les Suffragettes’. This endearing postcard could only have been produced in France because although the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) had more or less agreed a truce with Lloyd George’s government, in Britain the vote for women was still a very sensitive topic.

Perhaps one of the most famous posters of all time – Alfred Leete’s iconic recruiting poster depicting Lord Kitchener first appeared in September 1914 and was singlehandedly responsible for encouraging thousands of men to flock to the colours.

Alfred Leete’s iconic graphic first appeared as a cover illustration for London Opinion, one of the most influential magazines in the world, on 5 September 1914. Alfred Ambrose Chew Leete later contributed regularly to publications such as Punch magazine, the Strand Magazine and Tatler, and was well-known for his advertising posters for brands such as Rowntrees, Guinness and Bovril, and the Underground Electric Railways Company (the London Underground). But there’s no doubt that he will be ever remembered for his drawing of Kitchener.

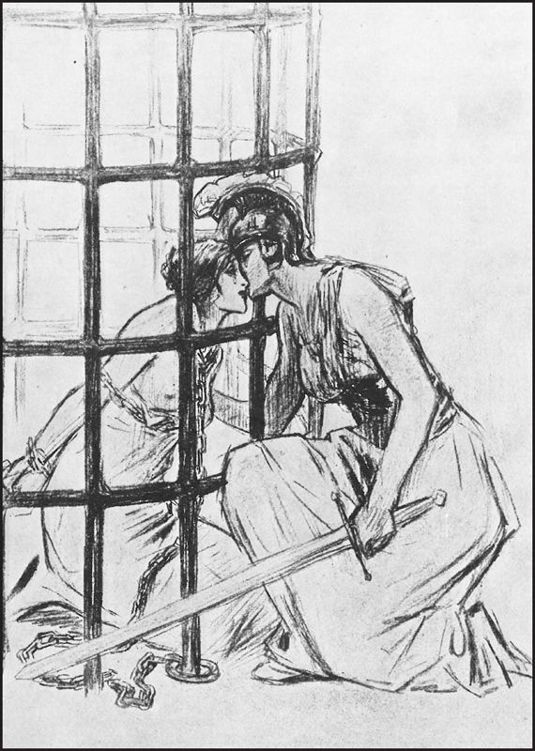

Other notable British posters and their creators included Bernard Partridge, whose stirring ‘Take Up the Sword of Justice’ was a rallying cry for recruits to Kitchener’s army.

Sir Frank William Brangwyn RA learned some of his creative skills in the workshops of William Morris, and the Anglo-Welsh artist, painter, watercolourist, virtuoso engraver and illustrator worked steadily into the 1950s; he was knighted in 1941.

Although Brangwyn produced over eighty poster designs during the First World War, he was not an official war artist. His poster of a Tommy bayoneting an enemy soldier – ‘Put Strength in the Final Blow: Buy War Bonds’ – caused deep offence in both Britain and Germany. Allegedly, even the Kaiser himself is said to have put a price on the artist’s head after seeing the image. Brangwyn’s 1915 poster for the National Fund for the Welsh Troops is typical of the artist’s combination of graphic and illustrative techniques.

‘Hello Blighty!’, No. 1 Observation Group, BEF postcard. It reads: ‘Compliments of the season to you and best wishes for the New Year. Cheerio! Bert’. A Christmas card from 1917. The smiling Tommy was unaware that 1918 would deliver a renewed German offensive.

Many other British artists contributed to the nation’s war effort, providing stirring designs for posters in particular. Other notable posters include ‘Song to the Evening Star’ by F. Ernest Jackson, ‘Their Home! Belgium, 1918’ by T. Gregory Brown and a striking one by an anonymous artist from the army’s publicity department: ‘Young men of Britain! The Germans said you were not in earnest. “We knew you’d come – and give them the lie!” Play the greater game and join the football battalion.’

After he was invalided out of the army due to an injury while in the trenches, Paul Nash, one of Britain’s greatest artists, who came to real fame during the Second World War, joined the other artists sent to the front in 1917 to record the carnage there. Nash’s modernist painting A Howitzer Firing emphasises the role and destructive potential of artillery, suggesting the damage modern technology could inflict on human flesh.

Other artistic giants, such as Sir William Orpen and Eric Kennington, were also engaged as official war artists alongside Nash.

During Orpen’s visit to the Western Front he produced drawings and paintings of privates, dead soldiers and German prisoners of war, many of which were used on posters and postcards by the Ministry of Information. Orpen’s most famous works, however, are his large paintings of the Versailles Peace Conference which captured the political machinations of the assembled statesmen. He presented over one-hundred of his original artworks to the British government on the understanding that they should be mounted in simple white frames and kept together as a single body of work. They are now in the collection of the Imperial War Museum in London.

Like Nash, Eric Kennington had been invalided out of the army early in the war. He served as an official War Artist from 1916 until 1919 and would do so again during the Second World War. Kennington’s first one-man show of The Kensingtons at Laventie at the Goupil Gallery 1916 caused a sensation. The artist had actually served in the 13th Battalion, The London Regiment, popularly known as ‘The Kensingtons’, and this magnificent painting actually depicts men from his own platoon and even includes a self-portrait. Kennington painted this tribute to his comrades after he was invalided out of the army in 1915.

The fine canvases of oil painters, though catching a mood and often, in an almost subversive way, revealing the inequities of the suffering of ordinary soldiers at the front, could only really be seen in art galleries or on the occasions when they travelled the nation to drum up contributions to national savings and war bonds. The art that most affected public opinion and reached the widest audience was that of the posterist.

Together with Alfred Leete’s famous portrayal of Kitchener back in 1914, possibly the other single most memorable poster of this period was the work not of a well-known artist but of a now little-remembered one, E.V. Kealey. ‘Women of Britain Say – Go!’, a 1915 recruiting poster depicting a mother, daughter and young son watching soldiers march off to war. Created for the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee, and printed in London, this poster was more than a patriotic call to arms. Showing a defenceless mother and her two young children bravely home alone while the local menfolk, their protectors, march off to war, this emotive design was more than enough to inspire even the most reluctant recruit to enlist. After the war Kealey continued designing similarly striking posters but his commissions came now from the burgeoning travel trade, cruises to Africa and the exotic Orient and the like, rather than official commissions.

French illustrators provided equally stirring designs to support their country’s war effort. Auguste Roll’s stirring 1916 poster showing a French nurse tending a sick soldier and ‘On les aura!’ (‘We’ll Get Them!’) by Jules-Abel Faivre, published the same year to raise money for the second government defence-loan drive and showing a much more vigorous Poilu charging forward rifle in hand as he encourages his comrades to follow, garnered enormous public support.

A graduate of the Paris School of Fine Arts, Charles Fouqueray was a master of lithography and used his talents to design a fine series of war posters. In one of them, ‘Le Cardinal Mercier Protege la Belgique’ (‘Cardinal Mercier Protects Belgium’) he portrayed the famous Catholic defender of Belgium, who, in the role of the shepherd protecting his flock, denounced the German occupation and especially the burning of the great Library of Louvain. Fouqueray also had a distinguished career as a mural painter and as a prolific illustrator for magazines and journals such as the Graphic and Illustration.

Another memorable poster, ‘The French Woman in War-Time’, by Georges Émile Capon, shows three women engaged in supporting the war effort by each either nursing young children, toiling on the farm or working in a factory at the lathe. Originally designed to promote a government film produced to encourage women to leave the comfort of home behind and do ‘their bit’ for the good of France instead, Capon’s illustration soon enjoyed wider distribution.

Adolphe Willette’s poster ‘Journée du Poilu. 25 et 26 Décembre 1915’ (‘Day of the French soldier’) depicts a Poilu’s Christmas leave from the front. One of the great artists of the belle époque, Adolphe Léon Willette is today best remembered for his lithographs illustrating the chansonniers of Montmartre, the solitary poet singer-songwriters who performed their own songs at the famous cabaret Le Chat Noir. In 1906, Willette achieved the highest honour for a French artist when he was appointed Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur.

Born in 1871, Jules Marie Auguste Leroux was a professor at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris for thirty years, a jury member of the committee of French Artists Society, an art teacher at the Academy de la Grande Chaumiere, and a knight of the Légion d’honneur. Despite his exalted position midst the higher echelons of Parisian Beaux-Arts, Leroux was not above creating posters in support of his nation’s war effort. The one he produced in support of war loans raised by the Comptoir d’escompte de Paris, a now long-gone bank founded in response to the financial shock caused by the revolution of February 1848, command particularly high prices among collectors.

Though it did not get embroiled in fighting until 1917, from early in the war the United States had leaned towards the Allied course and was especially unsympathetic to the German invasion and subjugation of Belgium. Even before Congress approved America’s entry on the side of the Allies American artists and illustrators had been heavily involved producing arresting graphics and when it became pretty clear that the United States would be drawn into the conflict, American artist and illustrator Joseph Pennell observed: ‘When the United States wished to make public its wants, whether of men or money, it was found that art – as the European countries had found – was the best medium.’

And after news of the alleged German atrocities in Belgium reached the United States, numerous posters bearing the image of the ‘Hun’ were repeatedly employed to arouse public animosity towards the enemy.

The Wilson government’s Division of Pictorial Publicity employed over 300 of the most prominent illustrators of the time to help with the propaganda efforts. Among them were artists such as C.B. Falls, E.H. Blashfield, Joseph Pennell, Howard Chandler Christy, Joseph Leyendecker, Jessie Willcox Smith and L.N. Britton.

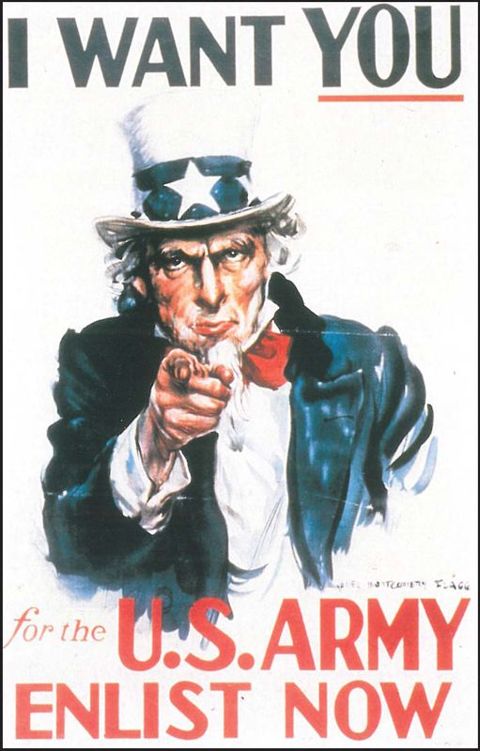

James Montgomery Flagg’s memorable poster of Uncle Sam: ‘I Want You for the US Army’, is as striking as Leete’s poster of Kitchener.

Perhaps the most famous American poster of the First World War was created by James Montgomery Flagg. Originally published as the cover for 6 July 1916 issue of Leslie’s Weekly, with the title, ‘What Are You Doing for Preparedness?’, Flagg’s portrait of ‘Uncle Sam’ went on to become one of the most famous posters in the world. More than 4 million copies were printed between 1917 and 1918, as the United States mobilised and sent its ‘dough boys’ to the far-off trenches in Europe.

A member of the first Civilian Preparedness Committee organised in New York in 1917, Flagg contributed nearly fifty works to support the United States war effort. Because of its overwhelming popularity, Flagg’s ‘Uncle Sam’ image was used again in the Second World War.

Other prominent artists working to support the United States’ propaganda machinery included Ellsworth Young, the noted landscape painter who was also a prolific supplier of illustrations to book and magazine publishers. Featuring a menacing silhouette of an armed Prussian soldier, spiked Pickelhaube on his head and carrying off his ‘war bounty’, a screaming maiden, his famous poster, ‘Remember Belgium’, produced in support of American bonds, caused a sensation.

Dutchman Louis Raemaekers’ cartoons were picked up for distribution by the British government in a series of propaganda pamphlets. The campaign was so effective, the Germans used their influence in the Netherlands to have Raemaekers tried for ‘endangering Dutch neutrality’. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George was so impressed by his work that he persuaded him to go the United States where his drawings were syndicated by Hearst Publications in an effort to enlist American help in the war. In 1917 United States President Theodore Roosevelt paid the artist a striking compliment saying: ‘The cartoons of Louis Raemaekers constitute the most powerful of the honorable contributions made by neutrals to the cause of civilization in the World War.’

Although of German decent, Adolph Treidler was another prolific artist working in support of the American war effort from 1917. Before this he illustrated numerous covers and also provided advertisement work for publications such as McClure’s, Harper’s, the Saturday Evening Post, Scribner’s and Woman’s Home Companion. His wartime propaganda posters in the First World War portrayed Women Ordnance Workers, otherwise known as WOWs, in munitions plants for the United War Work Campaign. Later on he also created wartime propaganda posters in the Second World War.

Vojtěch Preissig was a Czech typographer, printmaker, designer, illustrator, painter and teacher who had studied in Prague at the School of Applied Industrial Art before the war but moved to the United States as an art instructor. He designed a number of posters for the American government but is perhaps best known for one in particular, a striking graphic of a naval gun crew in action beneath the heading: ‘Find the range of your patriotism by enlisting in the Navy’. Preissig return to his native Czechoslovakia in the 1930s and following the Nazi invasion of his homeland he joined the Czech resistance. The artist was arrested in 1940 for doing graphic design work for V boj, a magazine of the resistance that had been outlawed by German authorities. He died in 1944 in Dachau concentration camp.

Numerous other American artists and illustrators made enormous contributions to their nation’s war effort but I have space to make mention of only one more and will single out Henry Raleigh for his 1918 poster promoting United States government bonds for the Third Liberty Loan. ‘Halt the Hun!’ features an American soldier restraining a German one from harming a woman and child, both of whom are cowering before the Teutonic giant. Like Raemaekers, Raleigh appealed to the sentimental side of his audience every time.

The Central Powers also possessed an abundance of artistic talent of course. In Germany painter Paul Plontke created an especially striking poster in 1917. ‘Fur die Kriegsanleihe!’ (‘For the War Loan!’) showed a cherub holding a German Army helmet filled with coins and beseeching the viewer to contribute.

Otto Lehmann’s poster ‘Stutzt Unsre Feldgraunen’ (‘Support our Field Greys. Rend England’s might – subscribe to War Loans’), published in Cologne early in the war, is a strikingly descriptive example of the high quality of German graphic design so lauded by the post-war book War Posters. Issued by Belligerent and Neutral Nations (see below).

Viennese painter, illustrator, industrial designer and graphic artist Erwin Puchinger was a major component of the Austrian art scene and a friend and contemporary of Gustav Klimt, among others. Puchinger worked in London, Prague and Paris but during the war he was obliged to support his nation. His famous 1915 war-loan poster depicting a classical image of a knight defending a woman and child from the spears of unseen attackers reflects the influence of the Vienna Secession, of which he was a major part.

Other notable designers include Oswald Polte, whose sentimental poster entitled ‘Collection of gold and jewels for the Fatherland – Pomeranian Jewel and Gold Purchase Week, 30 June 1918 – 6 July 1918’, depicting a hausfrau offering up her jewellery collection, contrasts vividly with Ludwig Hohlwein’s very graphic depiction of a powerful German soldier in full kit eating from his mess tin. Captioned ‘Preserves Strength and Energy’, both the striking simplicity and excellent drawing and the not so subtle double entendre are typical of the excellent designs to come from the Central Powers.

There are a couple of other great German artists worth mentioning and whose posters, if you can find them, are of particularly high value. F.K. Engelhard created many, especially striking posters. ‘Nein! Niemals! (No! Never!)’ shows a kepi-wearing French soldier greedily grabbing out at German territory across the Rhine. The irony of such horror that anything like this could happen to the Fatherland was not lost on Belgians, whose neutrality had been so cruelly ignored by Germany in 1914. In fact, it wasn’t only British and French news agencies that were filling newspapers with usually untrue stories of German atrocities. In 1914 the German Wolff Telegraph Agency caused a sensation among German readers when it wired a story about a French doctor who had allegedly been involved in an attempt to infect a well at Metz with plague and cholera bacilli. Also produced towards the end of the war and entitled ‘Anarchie’, depicting a giant knife-wielding King Kong-like ape stalking the streets, was another equally striking poster from Engelhard. This was created at the time of the German revolution in 1918 and the poster’s subtitle, ‘Misery and Destruction follow Anarchy’, left the reader in little doubt about the likely results of an authoritarian collapse and the rise of communism in Germany. As we know, the ferment of these times gave voice to National Socialism and the rise of Hitler. Austrian artist Roland Krafter put a more positive spin on Germany’s collapse in November 1918 as his fine poster ‘The Troops Home-Coming for Christmas’, showing upstanding German troops marching across the border with laurels in their Stahlhelms and carrying pillowcases full of presents, so clearly illustrates.

Hungary, Germany and Austria’s major ally, also provided the Central Powers with a number of fine artists who supported their nation’s propaganda machinery to stunning effect.

After studying art in Berlin, Paris and London, Mihaly Bíró, who was born in Budapest in 1886, returned to Hungary and ultimately became famous for his social protest posters in support of the Hungarian revolutionary movement within which he became political poster commissar of the Hungarian Socialist Republic in 1919. Before this, in 1918 as the Austro-Hungarian Empire was collapsing and being torn up by French and Serbian forces while Russian Communist troops also looked likely to enter the country in support of Béla Kun’s new Soviet Republic, the world’s second, Bíró produced a striking artwork suggesting the calamity of a Russian invasion. After the overthrow of the government, Bíró moved to the United States, but returned to Hungary in 1947 and died in Budapest the following year.

Another Hungarian poster artist, George Kürthy, had a far more traditional, illustrative, yet primitive, almost ‘peasant art’ style. His graceful line drawings, to me very reminiscent of the work of English artists Aubrey Beardsley, can be seen decorating many of Hungary’s war-loan posters during the 1914–18 conflict. As the war progressed and the effect of the Allied stranglehold on raw materials and other imports into occupied Europe began to be felt, the need for Austria-Hungary to look to its citizens for financial support became all the more critical.

In Britain, when the war finished, almost all of the propaganda machinery was dismantled. There were various interwar debates regarding British use of propaganda, particularly atrocity propaganda, most of which was found to be baseless. Commentators such as the politician Arthur Ponsonby, a member of the Union of Democratic Control, a British pressure group formed in 1914 and opposed to military influence in government, were active in refuting government claims against the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey). In 1928 Ponsonby’s book, Falsehood in War-Time: Propaganda Lies of the First World War, was published, exposing many of the alleged atrocities as either lies or exaggeration. Some modern commentators argue that one effect of Ponsonby’s revelations was reluctance in Britain to believe the stories of Nazi persecution during the Second World War until the Allied armies were confronted with the awful realities of the Holocaust and the terror of Nazi reprisals against civilians, which proved such stories to be true. In Germany, however, military commanders such as Erich Ludendorff, who with his superior Paul von Hindenburg had more influence on Germany’s strategy than the Kaiser himself, suggested that British propaganda had actually been instrumental in his country’s defeat. Adolf Hitler echoed this view, and when they assumed power the Nazis later adopted many of the techniques used by British propagandists during the 1914–18 war.

Now part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, British publisher A&C Black had a rich and independent history since it was founded in 1807 by Adam and Charles Black in Edinburgh. In 1851, the firm bought the copyright of Walter Scott’s Waverley novels for £27,000. Famous as the publisher of Who’s Who since 1897, in 1902 it published P.G. Wodehouse’s first book. Since then A&C Black’s extensive backlist has encompassed many books on visual arts, glass, ceramics and printmaking. Little wonder then that immediately after the cessation of hostilities in 1919 this publisher was to produce one of the best, illustrated reference books about war posters. The introduction to War Posters. Issued by Belligerent and Neutral Nations 1914–1919, selected and edited by Martin Hardie and Arthur K. Sabin (A&C Black Ltd, London, 1920), an 80pp. hard-back book littered with superb full-colour and half-tone plates, is illuminating:

The poster, hitherto the successful handmaid of commerce, was immediately recognised as a means of national propaganda with unlimited possibilities. Its value as an educative or simulative influence was more and more associated. In the stress of war its functions of impressing an idea quickly, vividly, and lastingly, together with the widest publicity, was soon recognised. While humble citizens were still trying to evade a stern age-limit by a jaunty air and juvenile appearance, the poster was mobilised and doing its bit.

Activity in poster production was not confined to Great Britain. France, as in all matters where Art is concerned, triumphantly took the field, and soon had hoardings covered with posters, many of which will take a lasting place in the history of Art. Germany and Austria, from the very outset of the War, seized upon the poster as the most powerful and speedy method of swaying popular opinion. Even before the War, we had much to learn from the concentrated power, the force of design, and the economy of means, which made German posters sing out from a wall like a defiant blare of trumpets. Their posters issued during the War are even more aggressive; but it is the function of a poster to act as a ‘mailed fist’, and our illustrations will show that, whatever else may be their faults, the posters of Germany have a force and character that make most of our own seem insipid and tame.

Here in Great Britain the earliest days of the war saw available spaces everywhere covered with posters cheap in sentiment, and conveying childish and vulgar appeals to patriotism already stirred far beyond the conception of the artists who designed them or the authorities responsible for their distribution.* This perhaps, was inevitable in a country such as ours. The grimness of the world-struggle was not realised in its intensity until driven home by staggering blows at our very life as a nation.

* While this is being written, our authorities are again placarding our walls with indifferent posters showing the advantages of life in the Army as compared with the ‘disadvantages’ of civil life, and embodying an undignified appeal to Britons to join the Army for the sake of playing cricket and football and seeing the world for nothing!

The preface beginning the section specifically dealing with British posters includes the following passage:

Shortly after the War began, an ‘Exhibition of German and Austrian Articles typifying Design’ was arranged at the Goldsmith’s Hall, to show the directions in which we had lessons to learn from German trade-competitors as to the combination of Art and economy applied to ordinary articles of commerce. The walls were hung with German posters, and one felt at once that while our average poster cost perhaps six times as much to produce, it was inferior to its German rival in just those vital qualities of concentrated design, whether of colour or form, and those powers of seizing attention, which are essential to the very nature of a poster.

While we have had individual poster artists, such as Nicholson, Pryde, and Beardsley, whose work has touched perhaps a higher level than has ever been reached on the Continent, our general conception of what is good and valuable in a poster has almost been entirely wrong. The advertising agent and the business firm rarely get away from the popular idea that a poster must be a picture, and that the purpose of every picture is to ‘point a moral and adorn a tale’. They seldom realise that poster art and pictorial art have essentially different aims. If a British firm wishes to advertise beer, it insists on an artist producing a picture of a publican’s brawny and veined arm holding out a pot of beer during closed hours to a policeman; or a Gargantuan bottle towering above the houses and dense crowds of a market-place; or a fox-terrier climbing on to a table and wondering what it is ‘master likes so much’ – all in posters produced at great expense with an enormous range of colour. The German, on the other hand – there was an example at the Goldsmiths’ Hall – designs a single pot of amber foaming beer, with the name of the firm in one good spot of lettering below. It is printed at small cost, in two or three flat colours; but it shouts ‘beer’ at the passer by.

However the editors conceded that ‘Our British war posters are too well known and too recent in our memory to require any lengthy introduction or comment,’ adding:

The first official recognition of their value to the nation was during the recruiting campaign of 1914. The Parliamentary Recruiting Committee gave commissions for more than a hundred posters, of which two and a half million copies were distributed throughout the British Isles. Hardly one of the early posters had the slightest claim to recognition as a product of fine art; most of them were examples of what any art school would teach should be avoided in crude design and atrocious lettering. Among the best and most efficient, however, may be mentioned Alfred Leete’s ‘Kitchener’. But if one compares Leete’s head of Kitchener, ‘Your Country Needs You’, with Louis Oppenheim’s ‘Hindenburg’, the latter, with its rugged force and reserve of colour, stands as an example of the direction in which Germany tends to beat us in poster art.

It is not surprising that following the carnage of the Great War, when nearly 16 million died and a further 21 million were wounded most individuals looked forward to peace and benevolent technological development, shunning militarism and arms manufacture. The future promised new homes with electric lighting and modern sanitation. In Britain ‘Garden’ cities were planned, featuring modern schools, hospitals, parks and playing fields. While totalitarian nations like Germany, Italy and Japan rearmed and argued that a nation’s future well-being depended on a strong military, other countries either sought to shelter behind supposedly impregnable fortifications such as France with its hi-tech Maginot Line or the security of negotiation, peace bought by treaty, such as those negotiated by the so-called appeasers like Britain’s Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. The Americans on the other hand, the only major power inadvertently to profit from the war, sought to isolate themselves from the quarrels of the old order, concentrating instead on further expanding their mighty industrial and commercial base.

Japan had been at war since 1931 when it invaded Manchuria.

‘Deutschland, Deutschland über alles’. A German postcard from January 1933, a period when Hitler still had to share power with President Hindenburg.

In 1915, a year after the Union of Democratic Control had been established, British liberal leaders had formed the League of Nations Society in an effort to promote a strong international organisation that could enforce the peaceful resolution of conflict. Later that year the League to Enforce Peace was established in the United States, striving for similar goals. These and other pacifistic initiatives helped to change attitudes and went some way towards the formation of the League of Nations, the covenant for which was signed at the Paris Peace Conference in June 1919.

As attitudes towards militarism changed numerous organisations joined the clarion call for an end to war. These included the War Resisters’ International, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, the No More War Movement and the Peace Pledge Union (PPU). The League of Nations also convened several disarmament conferences in the inter-war period, the most significant of which was the Geneva Conference.

Poster encouraging all those who believed in the rebirth of a new Germany under the leadership of Adolf Hitler to purchase the party’s bible, Mein Kampf.

In Britain there were also books about Hitler, not all of them hagiographies.

Revulsion of war was widespread in 1920s Britain, a nation mourning the loss of the flower of its youth. Novels and poems about the futility of war and the destruction of brave young souls on the threshold of life, forced into battle by misguided old fools, were published on a regular basis. Erich Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front is perhaps the most famous story and was made into a successful film by director Lewis Milestone. Other books which had a significant effect on the consciences of all right-thinking citizens included Death of a Hero by Richard Aldington and Cry Havoc by Beverley Nichols. A debate at the University of Oxford in 1933 on the motion ‘one must fight for King and country’ captured this change of mood when the motion was resoundingly defeated.

Another novel which was translated into a blockbuster movie at this time was Things to Come, a work of science fiction by H.G. Wells, published in 1933, which Alexander Korda lavishly shot in Britain in 1936. Set in the fictional British city of ‘Everytown’, the film’s narrative spans the years 1940 to 2036. The story begins by showing the discomfort felt by successful businessman John Cabal (Raymond Massey) who cannot enjoy Christmas Day 1940 because of news about a possible war. When conflict does come the depictions of aerial assault, bombing and gas attack are terrifying and went a long way to encouraging the public’s acceptance of the British government’s policy of appeasement in order to avoid such horrors.

In fact the appeasement policy of British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s government in the late 1930s wasn’t of course simply a reaction to public sentiment or a symptom of his heartfelt hatred for war. He felt a duty to try, as much as he could, to do what the League of Nations had palpably failed to do – thwart aggressors by the use of negotiation rather than military might. Though it had been established to mediate in territorial quarrels, the League had stood idly by when, in September 1931, Japan, a member of the League of Nations, invaded northeast China and established a new territory, Manchukuo.

The League’s policy of international cooperation and collective resistance to aggression, the policy of ‘collective security’ was further tested and found to be wanting in 1935 with Italian dictator Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia (Ethiopia) and again in 1936 when Hitler sent German forces into the previously demilitarised Rhineland. Even though the Führer’s officers had orders to withdraw if they met French resistance, the League did nothing.

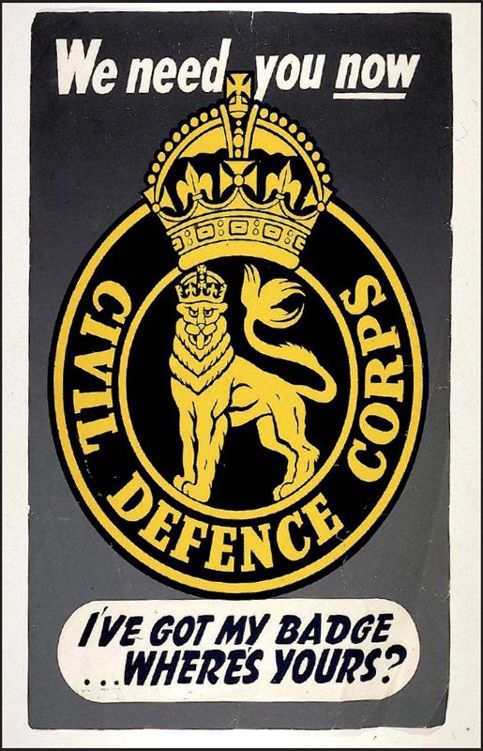

By the mid-1930s, with war looking inevitable, the Territorial Army was found to be woefully under strength and recruitment became a priority.

The Nazis took great comfort from the fact that there was considerable support for their claims upon the German-speaking Sudeten region of Czechoslovakia. An editorial in The Times on 7 September 1938 even called for it to be returned to Germany.

Similarly, Anschluss, the political union of Austria with Germany, achieved through annexation by Adolf Hitler in 1938, when the 8th Army of the German Wehrmacht crossed the Austrian border, met no resistance and was indeed greeted by cheering Austrians.

However, the real crisis came in 1938 and involved Czechoslovakia, or more properly Nazi claims on the largely German-speaking Sudeten part of that country, dismembered from the Reich at Versailles. In September, Chamberlain flew to Berchtesgaden, the Führer’s Bavarian holiday home, to negotiate directly with Hitler, in the hope of avoiding war. Demanding that the Sudetenland should be absorbed into Germany, Hitler convinced Chamberlain that refusal meant war. The British and French governments urged the Czech president to agree and in a stroke Czechoslovakia lost 800,000 citizens, much of its industry and its mountain defences in the west. Landing back at Croydon aerodrome, Chamberlain claimed he had secured ‘Peace For Our Times’ and the British, who had begun handing out gas masks and practising ARP (Air Raid Precautions), could breathe a sigh of relief. The Air Ministry, which had secretly been asking the Prime Minister to wait until 1939 before he went to war, also exhaled – there was still time to build the modern Spitfires they knew were essential to securing air superiority above Britain.

Many, of course were horrified at yet another example of democracy’s weakness in the face of bellicose militarism. In February 1938, Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden resigned from the government, telling the House of Commons:

I do not believe that we can make progress in European appeasement if we allow the impression to gain currency abroad that we yield to constant pressure. I am certain in my own mind that progress depends above all on the temper of the nation, and that temper must find expression in a firm spirit. This spirit I am confident is there. Not to give voice to it is I believe fair neither to this country nor to the world.

In answer to Eden’s resignation, backbencher Winston Churchill, one of the lone voices who, throughout the 1930s had warned against German rearmament and Nazi ambition, told the Commons:

The resignation of the late Foreign Secretary may well be a milestone in history. Great quarrels, it has been well said, arise from small occasions but seldom from small causes. The late Foreign Secretary adhered to the old policy which we have all forgotten for so long. The Prime Minister and his colleagues have entered upon another and a new policy. The old policy was an effort to establish the rule of law in Europe, and build up through the League of Nations effective deterrents against the aggressor. Is it the new policy to come to terms with the totalitarian Powers in the hope that by great and far-reaching acts of submission, not merely in sentiment and pride, but in material factors, peace may be preserved. A firm stand by France and Britain, under the authority of the League of Nations, would have been followed by the immediate evacuation of the Rhineland without the shedding of a drop of blood; and the effects of that might have enabled the more prudent elements of the German Army to gain their proper position, and would not have given to the political head of Germany the enormous ascendancy which has enabled him to move forward. Austria has now been laid in thrall, and we do not know whether Czechoslovakia will not suffer a similar attack.

It should not be forgotten that as a backdrop to the truly momentous events mentioned above, between July 1936 and April 1939 the bloody Spanish Civil War proved a further challenge to European peace and served as a useful testing ground for much of Hitler’s new weaponry, especially his Luftwaffe – many of the German Condor Legion pilots who flew in support of the nationalist General Franco’s rebellion would see action against the RAF in the Battle of Britain. Similarly, volunteers to the International Brigade which supported the elected, republican government, notably Britain’s Tom Wintringham and America’s ‘Yank’ Levy, learned valuable lessons in guerrilla fighting which would prove of enormous value to the Home Guard and Churchill’s super-secret Auxiliary Units.

I think this is one of the most interesting pieces of wartime ephemera the collector could possess. Though dropped over Britain by the thousand, Hitler’s ‘Last Appeal to Reason’ is also one of the rarest items – the majority which floated earthward were retrieved and used as loo paper!

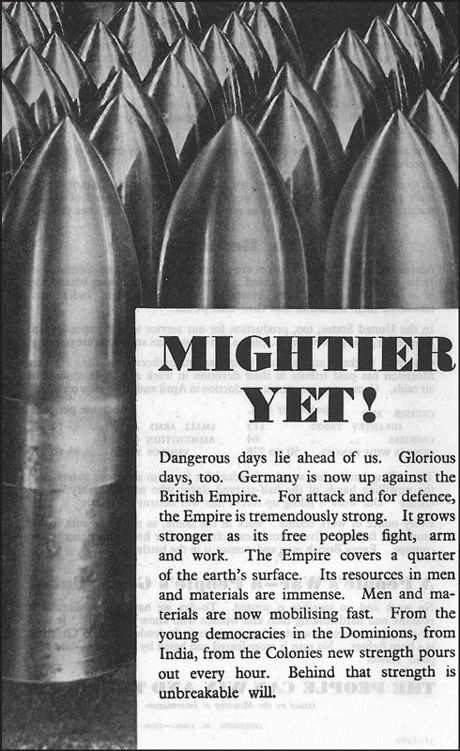

‘Mightier Yet!’ This leaflet compares production in April 1940 with that of June and explains that everything has improved. ‘Dangerous times lie ahead of us. Glorious days, too. Germany is now up against the British Empire. For attack and for defence, the Empire is tremendously strong. It grows stronger as its free people’s fight, arm and work.’ Ministry of Information, 1940.

Per L’onore Per La Vita Legione SS Italiana’. Italian recruiting poster for the admission into Germany’s Waffen SS. Of the 15,000 men who volunteered for service only 6,000 were considered suitable enough to meet the exacting standards required.

In fact, several organisations already existed to publish and distribute these new learnings among Britain’s regular and more clandestine forces. The largest and most well-known was His Majesty’s Stationery office (HMSO), owned and operated by the British government, which came into being during the 1780s when the British Parliament undertook an audit of expenditure and discovered that the government used too much paper. As a result an official stationer accountable to the Treasury was established and continued to grow with the consequence that independent contracts ceased, the last of which was terminated in 1800.

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the Treasury was forced to recall all gold coinage to finance war preparations and the government directed the Stationery Office to arrange for the printing, on penny stamp paper – the only secure quality stock available – of one pound and, later, 10 shilling notes. The war put incredible strains on the Stationery Office and although wartime shortages forced bureaucrats to reduce the amount of printed items they had previously relied upon, orders for millions of ration books and public notices cancelled out the benefits of such economies.

Pre-war RAF recruitment poster by Norman Keane.

‘Come and help with the Victory Harvest’ (artist unknown). Come ye land girls all.

By the mid-1930s, the Stationery Office itself employed more than 3,000 people, this dramatic increase in its capacity and capabilities was put to good use when, by the end of the decade, the threat of another European war encouraged the government to prepare, in secret, numerous handbooks and leaflets advising the public about what to do in the event of attack from the air and, especially, about the nation’s preparations for dealing with chemical warfare, poison gas delivered by enemy bombers. In fact HMSO supervised the printing of 78 million ration books and hundreds of thousands of instruction manuals on everything from cooking to air raids. The threat of invasion, the potential evacuation of all government operations from London and the autumn night Blitz in 1940 encouraged HMSO to establish a second press facility in Manchester.

The nation’s official stationer wasn’t the only publisher of information and advice. Many private firms produced an abundance of useful handbooks and pamphlets, many of them officially sanctioned.

In Britain, Gale & Polden probably rank as the most prolific producer of information during both world wars. In 1868 James Gale opened a bookshop near Brompton Barracks at Chatham, on the Medway in Kent. Soon after investing in a printing press he won lucrative contracts to supply the Headquarters of the Chatham Military District, among them the annual publication of the Garrison Directory. Together with a variety of important naval and army establishments, HMS Victory was built there, Chatham was also the home of the Royal Engineer Establishment, renamed the School of Military Engineering in 1868.

James Gale’s first book, Campaign of 1870–1: The Operations of the Corps of General V. Werder by Ludwig Lohlein, was published in 1873 and his company soon expanded. In 1875 he employed two apprentices, one of whom, 16-year-old Thomas Ernest Polden, was instrumental in introducing a range of improvements into the production side of Gale’s business. Polden was soon made senior partner and went about extending the company’s distribution network throughout garrisons and dockyards across the Home Counties and eventually throughout Britain. Expansion was such that on 10 November 1892 the company was incorporated as Gale & Polden Ltd.

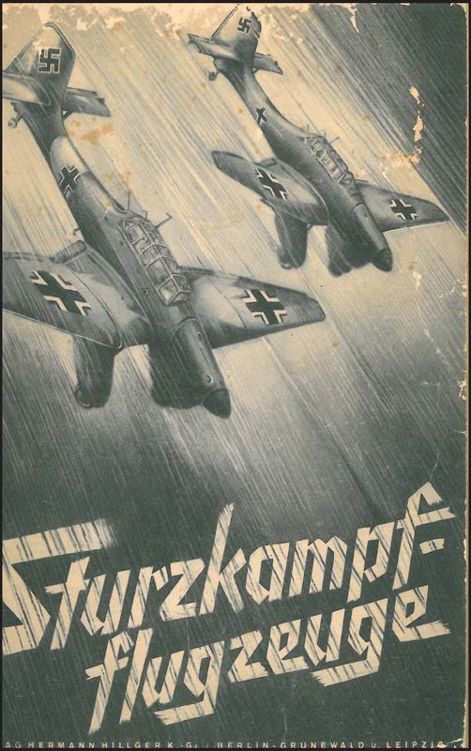

Until it was bloodied in the Battle of Britain during the summer of 1940, and then very quickly withdrawn from the campaign, the Junkers Ju-87 Stuka reigned supreme above the unfolding battlefields of Europe. This book, published by Berlin’s Verlag Herman Hiller in 1941, is packed with colour illustrations about every aspect of this infamous aircraft.

By the turn of the twentieth century Gale & Polden had relocated to Aldershot, then the largest British Army base in Great Britain. Things continued on the up and up and in 1916 Gale & Polden was even granted a Royal Warrant. A huge proportion of the handbooks used by British soldiers, sailors and airman during the First World War originated from Gale & Polden’s Aldershot factory. Even a major fire at the factory in 1918 achieved little more than disruption with the effect that when another major war loomed at the end of the 1930s, Gale & Polden were in an excellent position to supplement HMSO with official publications. By the late 1950s Gale & Polden had acquired a number of smaller printing firms, including larger rivals such as their main competitor in Aldershot, John Drew Ltd. In 1963 Gale & Polden was taken over by the Purnell Group, which in 1964 merged with another printing company, to form the new British Printing Corporation (BPC), the largest printing company in Europe. When Robert Maxwell gained control of BPC in 1981, naming his new company Maxwell Communications, Gale & Polden was finally closed.

Though Gale & Polden seem to have benefitted most as far as picking up business HMSO might have been expected to have produced themselves either at their London or Manchester print works, several other publishers benefitted from total war. Among them, Key, Bernards and Nicholson & Watson did particularly well. Interestingly, the latter house was once home to the late Graham Watson, a British literary agent who represented such literary giants as John Steinbeck and Gore Vidal. After joining Nicholson and Watson in 1934, a publishing firm co-founded by his elder brother and financed by their father, in 1947 Graham Watson moved to London literary agency Curtis Brown, as head of its American book department. He worked there for thirty years, the last fifteen as managing director, representing a total of forty authors which together with American giants also included British luminaries like Daphne du Maurier, Randolph Churchill, John O’Hara and C.P. Snow.

Founded in 1909, Flight (now Flight International) the British produced global aerospace weekly and the world’s oldest continuously published aviation news magazine, was another publisher of specialist information which appeared as wartime paper restrictions allowed to keep enthusiasts up to date with developments in aircraft design and performance. Similarly, the Aeroplane (now Aeroplane Magazine), which first appeared in 1911, was Flight’s great rival. Between them these publications met the insatiable demand for recognition handbooks of the sort devoured by ‘air mad’ school boys and used by those employed on observation duties, most notably the volunteers of the Observer Corps, an organisation established in 1925 to keep a lookout for enemy aircraft and which, as a result of its role during the Battle of Britain, was awarded the ‘Royal’ prefix in April 1941.

It is just as well that Britain possessed the machinery to communicate with its concerned citizenship, keeping nervous civilians informed, albeit with the official government approved line, about developments that threatened another European war.

Popular history records that British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain once again backed down in front of Nazi aggression during the Munich Crisis of September 1938. However, we now know that the government was simply playing for time and that Chamberlain’s repeated appeasement wasn’t the result of a lack or mettle but an expedient delaying tactic which bought his country time to rearm and make the necessary adjustments to its economy to go onto a war footing. Nevertheless, as early as April 1939, five months before Britain declared war with Germany, the government began to get its propaganda ducks in a row, or at least attempted to.

An interesting piece of British propaganda aimed at Portugal, its oldest ally. Neutral during the Second World War, Portugal traded with both the Allies and the Axis and was a focus for espionage by both sides. The message here lampoons Goering’s boast that no bombs would every fall on the Ruhr and then goes on to remind the reader that in 12 months the RAF has bombed the region 530 times.

During the early spring the reborn, but still as yet secret, Ministry of Information commissioned a series of public information posters for use in the event of another European war. Sent to the printers in August, within weeks, budgeted at a cost of £20,600, nearly 4 million posters were printed, distributed and stocked in warehouses in time to be put into use immediately war was declared on 3 September 1939.

Though undoubtedly produced with the best intentions, this first batch of British home-front propaganda posters, each sporting bold sans-serif type reversed out in white on a plain signal red background arranged beneath a white monarch’s crown, proved a disaster. The public considered one design in particular, centred type arranged in five lines one on top of the other, reading: ‘Your courage Your Cheerfulness Your Resolution WILL BRING US VICTORY’, patronising and laced with the same old class-ridden ironic rhetoric that many assumed was a thing of the past. Though readers liked the red background, thinking this a cheerful and positive colour, the emphasis on the repeated ‘Yours’, underlined each time for additional significance, simply meant that the working class would once again carry the burden of front-line fighting or working long hours in the factories if they were engaged on the home front. Many observers thought that ‘US’ stood for the ruling elite. It would be the same old, same old as far as suffering was concerned.

Curiously, one piece of publicity produced as part of this quickly cancelled and now long-forgotten campaign has become very much part of the cultural fabric of twenty-first-century Britain – the rediscovered ‘KEEP CALM AND CARRY ON’ poster.

In 2000, one of the owners of Barter Books, Stuart Manley, was going through a box of dusty old books bought at auction when at the bottom of the pile he discovered a curious piece of folded paper. Upon opening and flattening the item, what looked like an old war-time poster was revealed to Stuart. He and his wife Mary liked it so much they decided to frame it and proudly display it in their shop above the till. It went down so well with customers, many of whom enquired whether they could purchase copies, that Barter Books decided to run-off and sell facsimile copies.

The ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ poster was the third of three designs commissioned before the fighting actually started. Together with 1 million impressions of the ‘Your Courage … Will Bring Us Victory’ design, nearly 600,000 versions of a similar poster simply reading ‘Freedom is in Peril’ were printed.

Of the now ubiquitous ‘Keep Calm’ poster, Dr Bex Lewis (PhD, FHEA, PCP), Research Fellow in Social Media and Online Learning at Durham University and who has done a great deal of research into the provenance of early British propaganda posters, has written:

Although some may have found their way onto Government office walls, the poster was never officially issued and so remained virtually unseen by the public – unseen, that is, until a copy turned up more than fifty years later in that box of dusty old books bought in auction by Barter Books.

The Ministry of Information commissioned numerous other propaganda posters for use on the home front during the Second World War. Some have become well-known and highly collectable, such as the cartoonist Fougasse’s ‘Careless Talk Costs Lives’ series. But we will probably never know who the graphic artist was who was responsible for the ‘Keep Calm’ poster, but it’s to his or her credit that long after the war was won, people everywhere recognize the brilliance of its simple timeless design and still find reassurance in the very special ‘attitude of mind’ it conveys.

In February 2012, while I was researching this book, an article in the Daily Mail newspaper began: ‘A collection of “Keep Calm and Carry On” posters that are believed to be the only surviving originals in Britain have emerged on the Antiques Roadshow.’ Apparently, the posters uncovered on the Roadshow at St Andrews University were given to Moragh Turnbull, from Fife, by her father William, who served as a member of the Royal Observer Corps. The feature continued:

Mr Turnbull was given about 15 to put up close to his home but by the time he received them, the threat of a German invasion had waned. He kept them rolled up in an elastic band at his home before passing them on to his daughter – who only realised their true value after taking them to an Antiques Roadshow event. Roadshow expert Paul Atterbury told Miss Turnbull that she was ‘probably sitting on the world’s only stock’ of the famous posters – and they are worth several thousand pounds. Mrs Turnbull told the presenter: ‘I may keep hold of the posters for a few years and sell them for a pension fund.’

It wasn’t just those on the home front who were subjected to a barrage of posters telling them what and what not to do. Those in the armed services received their fair share too. This poster reminds antiaircraft gunners to make sure they knew the particular recognition signals used to identify friendly aircraft on any given day.

Formed in 1925, the Observer Corps was awarded the title prefix ‘Royal’ by the King in April 1941, in recognition of service carried out during the Battle of Britain.

Because the government was concerned about being seen to limit civil liberties in a way their Fascist enemies took for granted, the new Ministry of Information did not formally exist until 4 September 1939, the day after hostilities commenced. However, since 1935 the Committee of Imperial Defence, established in 1902 to create a strategic vision defining the future roles of Britain’s arms of service, had been busy putting the building blocks in place. When it did emerge from concealment the department’s functions were threefold: news and press censorship; home publicity; and overseas publicity in Allied and neutral countries.

Four Ministers headed the MOI in quick succession: Lord Hugh Macmillan, Sir John Reith and the restored Duff Cooper (the most public critic of Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement policy inside the Cabinet, he had resigned the day after the 1938 Munich Agreement) before the Ministry settled down under Brendan Bracken in July 1941. Supported by Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the press, Bracken remained in office until victory was clear.

The Home Publicity Division (HPD) was coordinated by Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery, and Harold Nicolson, husband of Vita Sackville-West. Nicolson also served as Churchill’s official censor. Interestingly, Kenneth Clark was also responsible for the successful relocation and storage of most of Britain’s finest paintings. We have him to thank for the fact that they all survived the London Blitz. The Home Publicity Division undertook three types of campaigns, those requested by other government departments, specific regional campaigns and those it initiated itself. The General Production Division (GPD), managed the printing, producing work in as little as a week or a fortnight, when normal commercial practice might require three months.

Through the Home Intelligence Division (HID), the MOI collected reactions to general wartime morale and, in some cases, specifically to publicity produced. In fact, the government often turned to Mass Observation, a project to study the everyday lives of ordinary people in Britain, established in 1937 by the anthropologist, journalist, soldier and, well, polymath Tom Harrisson, with filmmaker Humphrey Jennings and the poet-cum-sociologist Charles Madge. The authorities first found Mass Observation useful during the abdication crisis of 1936, when King Edward VIII decided to marry divorcée Wallis Simpson and forsake the throne. The views of the man in the street proved invaluable to the government’s appreciation of public opinion. Actually, in 1939 Mass Observation was one of the most vocal critics of the Ministry of Information’s initial series of posters.

Fortunately, the series of posters which replaced the expensively pulped initial outlay of the Ministry of Information were received far more favourably. Created by the Punch cartoonist Cyril Bird, pen name, ‘Fougasse’, who gave his time freely for such government commissions, the ‘Careless Talk Costs Lives’ campaign is an example of the best in British publicity. To this day it is still used as an example of the perfect combination of matter of fact copy writing teamed with appealing illustrations. The message might have been deadly serious but the execution was entertaining and people looked at these posters and took the message on board. Humour got the point across. A careless comment on a bus or in an Underground train might, just might, be over heard by an enemy agent and a bit of innocent chit-chat about the destination of a loved one returning to his regiment from leave might result in disastrous consequences.

By the late 1930s Britain possessed a well-established graphics industry, developed to support the growth in consumerism and an emerging market eager to purchase the various mass-produced labour saving mechanical devices which ranged from toasters, vacuum cleaners and washing machines at one end to automobiles at the other. The new MOI was able to comb through the cream of the crop of this burgeoning creative industry and contract the best designers available.

Together with ‘Fougasse’, other notable graphic designers working in Britain at this time included Abram Games, F.H.K. Henrion, Herbert Tomlinson, Reginald Mount, Philip Zec, Harold Forster, Jan le Witt and the Pole George Him.

Sadly, though the authorities could call upon a network of some of the best creative talent around, sometimes the concepts they asked them to execute fell far short of the mark. Following the debacle of the retreat from Dunkirk, a potential disaster which the British Army only narrowly avoided, yet even though most of the troops were plucked from the occupied continent they had left their best weapons and equipment in France, the powers that be assumed the Allied collapse must be the result of enemy subterfuge when, of course it was simply the reward the Wehrmacht deserved for employing the modern tactic of blitzkrieg. Convinced that the French Army was defeated by an insidious fifth column of spies and defeatists, the British government’s next big poster campaign was designed to put an end to defeatist talk, if it existed at all, and gossip that might help the enemy. On the theme of the ‘Silent Column’, the new campaign featured the rather two-dimensional characters of Miss Leaky Mouth, Mrs Glumpot and Mr Knowall – none of them to be trusted.

This campaign was posted in public areas at the same time as a wave of prosecutions took place under the auspices of the draconian Regulation 18B of the Defence (General) Regulations 1939, which allowed the internment of people suspected of being Nazi sympathisers and the suspension of habeas corpus, which, dating back to the Magna Carta required that a person under arrest had to be brought before a judge or jury before he or she was sentenced. Given that ordinary citizens were being told that the fight was against authoritarian totalitarianism and to preserve their democratic freedom, this campaign touched a raw nerve. In his diary Harold Nicolson confided that ‘the Ministry of Information was in disgrace again’.

The Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Families Association was founded in 1885 by James Gildea. In 1919, after the RAF was formed, it became a charity and changed its name to the Soldiers’, Sailors’ and Airmen’s Families Association (SSAFA).

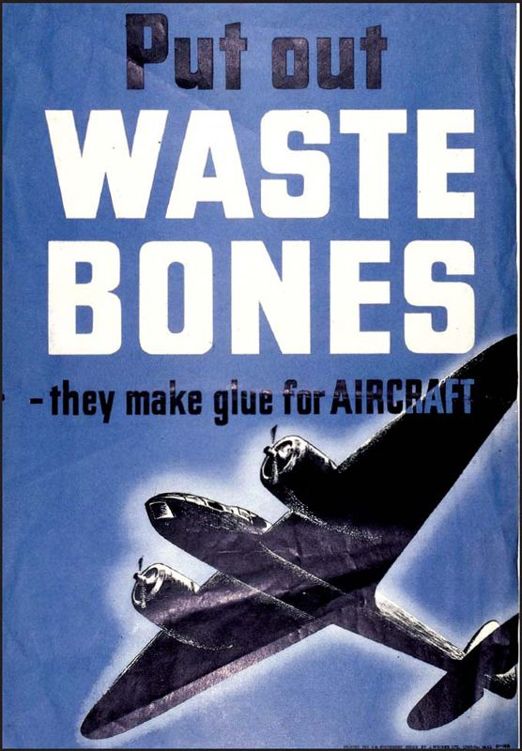

Issued by the National Savings Committee and printed by His Majesty’s Stationery office (HMSO), this poster showed prospective savers what their contributions were helping to support.

As mentioned earlier, the Ministry of Information really found its feet under the governance of Brendan Bracken, the Irish-born businessman and Tory Cabinet minister who after the war was responsible for the merger of the Financial News into the Financial Times, creating the financial daily we know today. Churchill appointed him as his parliamentary private secretary soon after the outbreak of the Second World War and Bracken replaced Duff Cooper as Minister of Information on 21 July 1941.

Bracken’s publishing experience – he had joined Eyre & Spottiswoode in 1923 and in 1925 became a director of the publishing company – was a real advantage. He also edited the Financial News, the Banker and the Practitioner before being promoted to managing director of the Economist in 1928.

Although he argued against either appealing to public sympathy or lecturing the masses as if they were children, saying the former made them furious, the latter resentful, he wasn’t beyond criticism himself for his forthright view about how things should be done. One of his employees, Eric Blair, later George Orwell, who worked under Bracken on the BBC’s Indian Service, customarily referred to Bracken by his initials, B.B., the same as those used for his character Big Brother in Nineteen-Eighty-Four, his post-war book warning of the dangers of an authoritarian state. Orwell resented wartime censorship and doubted the need to manipulate information, something he felt Bracken’s office managed with a Machiavellian hand.

But, to stay on course every ship needs a firm hand on the tiller and as we shall see throughout the pages of this book Bracken managed to supervise a series of very successful campaigns which in their small way went some way to supporting Britain’s war effort. We’ve the combined talents of the Ministry of Information to thank for giving us phrases such as ‘Dig For Victory’, ‘Cold’s and Sneezes Spread Diseases’, ‘Go To It!’ and ‘Don’t be Fuel-ish’ and these messages resonated across the ages.

It should not be forgotten that while Britain’s authorities were girding themselves to face a war they had avoided for so long, there were still vocal splinter groups who continued to oppose another European war, especially one hard on the heels of a conflict that had wrought such calamity upon the Continent and its constituent populations, and also those who actively supported the kind of totalitarianism, fascism, which was proving so popular in Italy and Germany.

The main players upon this stage included people such Gerard Vernon Wallop, 9th Earl of Portsmouth, better known as Viscount Lymington. He edited New Pioneer magazine from 1938 to 1940 and founded the British Council Against European Commitments in 1938, with William Joyce. Joyce, better known as ‘Lord Haw-Haw’, was an Irish-American fascist politician who famously broadcast Nazi propaganda to the United Kingdom during the Second World War and was hanged for treason at Wandsworth prison for his treachery when, contrary to his pronunciations, the Allies proved victorious.