APPENDIX 3

Publishing was in the blood of Penguin founder Sir Allen Lane. In 1919 he joined the family firm, Bodley Head, working as an apprentice to his uncle and founder of the company, John Lane. By 1925 Allen had risen to become managing editor but, following a dispute with some of Bodley Head’s other directors about the wisdom of publishing James Joyce’s controversial book Ulysses, Lane and his brothers Richard and John decided to establish the quite separate Penguin Books division in 1935. It became a separate company the following year. Lane’s innovation was the introduction of quality paperbacks, good reads for everyone but cheap enough to be sold from vending machines. Penguin paperbacks were a run-away success and Lane went on to start the Pelican and Puffin brands in 1937 and 1940 respectively. Penguin became world famous when it published an unexpurgated edition of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover as a means of testing the Obscene Publications Act 1959.

Penguins are famous for their simple yet coordinated jacket designs; three horizontal bands, the upper and lower areas colour-coded according to which series they belonged to and, in the central white panel, the author and title printed clearly in Gill Sans type. A 21-year-old office junior, Edward Young, created the iconic Penguin logo.

During the war years Penguin published many bestselling manuals such as Keeping Poultry and Rabbits on Scraps and Aircraft Recognition. It also supplied its popular books to the services and POWs. When rationing was introduced in March 1940 a paper quota was allocated by the Ministry of Supply to each publisher as a percentage of the amount used by that firm between August 1938 and August 1939 – fortunately this had been an enormously profligate period for Penguin, whose books where everywhere. So, Penguin’s paper supplies weren’t as restricted as other publishers’ quotas.

Blackmail or War by Geneviève Tabouis (1938). French historian and journalist Geneviève Tabouis repeatedly warned about Hitler’s rise and Nazi re-armament. Writing in dismay about the reality of German unification with Hitler’s homeland of Austria, the author said: ‘Chancellor Schuschnigg did not yield to force but the threat of force and there is no knowing what the ultimate effects of the Anschluss may be.’

The Air Defence of Britain by G. T. Garratt, R. Fletcher, L.E.O. Charlton (1938). ‘Three well-informed authoritative writers discuss urgent problems of Air Defence’. One of them, Air Commodore Lionel Evelyn Oswald Charlton, was already a well-known writer on the subject. While serving as a British infantry officer he fought in the Second Boer War. During the First World War, Charlton rose to high rank within the Royal Flying Corps and then joined the Royal Air Force on its creation. In 1928 Charlton resigned his position as the RAF’s Chief Staff Officer in Iraq because he objected to the bombing of Iraqi villages.

What Hitler Wants by E. O. Lorimer (1939). ‘Dedicated in sorrow and mourning to the memory of the Democratic Republic of Czechoslovakia whose heroism, steadfastness and self-restraint, during the dark days of September 1938 have won her people a fame as imperishable as the infamy of her foes and the humiliation of her friends.’

Why Britain is at War by Harold Nicolson (1939). English diplomat, author, diarist and politician, Sir Harold George Nicolson was also the husband of writer Vita Sackville-West. ‘This book describes in simple terms the stages by which the French and British governments became convinced that Herr Hitler was determined to adopt methods of force in place of the appeasement which they continually offered him.’

Stalin and Hitler by Louis Fischer (1940). ‘The reasons for and the results of the Nazi-Bolshevik pact’. The son of Orthodox Jews who had fled the pogroms of Alexander III, Louis Fischer was an early supporter of Stalin. He also supported the International Brigades under the control of Joseph Stalin during the Spanish Civil War. In 1938 Fischer returned to the United States where he published Stalin and Hitler, which attempted to rationalise the startling reasons for the non-aggression pact between such polar opposites.

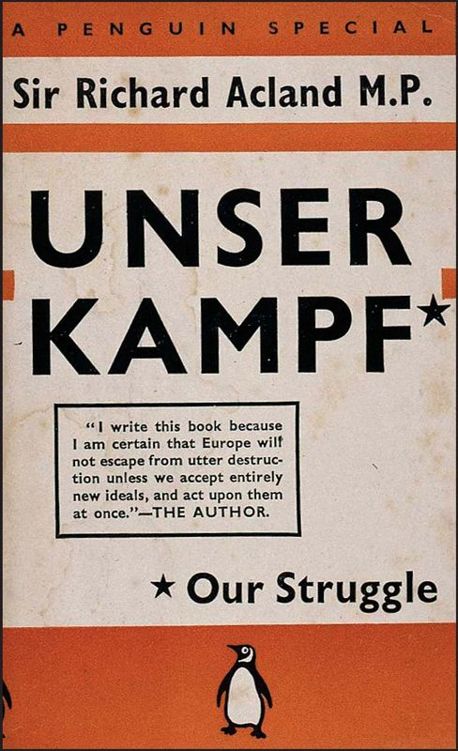

Unser Kampf (Our Struggle) by Sir Richard Acland MP (1940). ‘The trouble about this war is that it is the second such war to make the world safe for democracy and fit for heroes to live in. Because nothing was done to stop aggression in Manchuria, Abyssinia, Spain, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Lithuania or Albania this war must be fought with a clear policy for a new post-war order.’ Acland was one of the original founders of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

Must the War Spread? by D.N. Pritt KC, MP (1940). Barrister and Labour Party politician Denis Nowell Pritt visited the Soviet Union in 1932, as part of the New Fabian Research Bureau’s ‘expert commission of enquiry’. A supporter of Stalin, George Orwell said he was ‘perhaps the most effective pro-Soviet publicist in this country’. In 1940 Pritt was expelled from the Labour Party for defending the Soviet invasion of Finland. Must the War Spread? was ultra-sympathetic to the Soviets and led him to be greatly disliked by many of his colleagues.

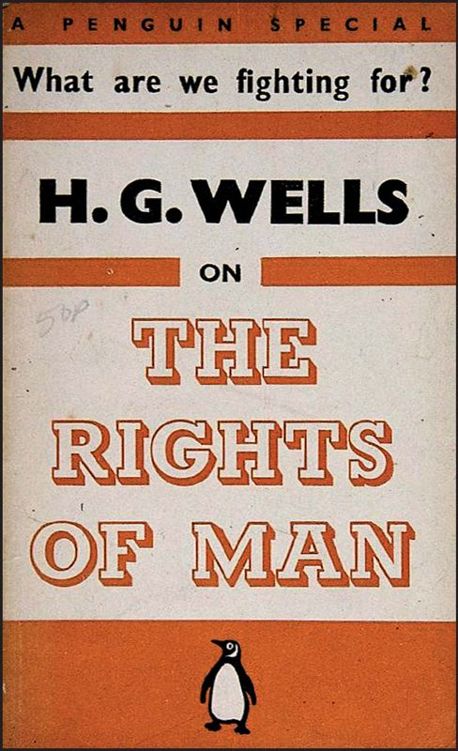

The Rights of Man by H.G. Wells (1940). Many observers contend that in putting before an international public the idea that international consensus about the ‘Rights of Man’ had to be part of any attempt at building a better international society post-war, the famous author of The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds laid the foundations for the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. However, Wells, who died in 1946, would never live to see his ideas become reality.

Science in War (1940). ‘The full use of our scientific resources is essential if we are to win the war. Today they are being half used. Written by twenty-five scientists, all of whom speak with authority in their own fields.’

The Real Cost of the War by J. Keith Horsefield (1940). Economist Horsefield (author of The International Monetry Fund 1945–65) ‘explains the dangers of inflation, the difficulties of War Debt, and the prospects of population changes in war-time, and discusses the question of post-war reconstruction’.

People in Production. An enquiry into British war production. A report prepared by Mass Observation for The Advertising Service Guild (1942). At a time when there was some concern about possible inefficiencies in British industry Mass Observation surveyed some eighty firms, speaking to management, foreman, shop-floor workers and trade unionists. This popular paperback was a sequel to Britain by Mass-Observation – The Science of Ourselves (1939), in which the work of Tom Harrison and Charles Madge’s team of well-meaning eavesdroppers threw new light on to many aspects of British society.

Wartime ‘Good Housekeeping’ Cookery Book, compiled by the Good Housekeeping Institute (1942). Now one of the rarest and most collectable Penguin Specials, this collection of recipes from the famous magazine founded in Massachusetts in 1885 and its august ‘research institute’, which can be traced back as far as 1900 with the establishment of its pioneering ‘Experiment Station’, proved a real winner with cooks trying to make ends meet with the meagre products of rationing.

Bibliography

Briggs, Asa. Go To It!, Mitchell Beazley, 2000

Doyle, Peter. British Postcards of the First World War, Shire Publications, 2012

Evans, Harold. Pictures on a Page, Pimlico, 1978

Gloag, John. Modern Publicity in War, The Studio Publications, 1941

Hardie, Martin and Sabin, Arthur K. (eds and selectors). War Posters. Issued by Belligerent and Neutral Nations 1914–1919, A & C Black Ltd, 1920

Lewis, John. Collecting Printed Ephemera, Studio Vista, 1976

Low, David. Years of Wrath: A Cartoon History: 1932–1945, Victor Gollancz, 1949

Make Do and Mend, Ministry of Information, 1943, IWM facsimile, 2007

Nelson, Derek. The Posters That Won The War, Motorbooks International, 1991

Nelson, Derek. The Ads That Won The War, Motorbooks International, 1992

Overy, Richard. The Road to War, 2nd edn, Penguin, 1999

Railway Posters and the War, Railway Gazette, 1939

Souter, Nick and Tessa. Illustrator’s Source Book, Macdonald Orbis, 1990

The Protection of Your Home Against Air Raids, HMSO, 1938, Old House Books facsimile, 2012

The Wipers Times, Introduction by Christopher Westhorp, Conway, 2013

Thomas, Vicki (ed.). Mabel Keeps Calm and Carries On – The Wartime Postcards of Mabel Lucie Attwell, The History Press, 2013

Walker, Susannah. Home Front Posters of the Second World War, Shire Publications, 2012