CHAPTER 2

Those left at home in Britain during both world wars were never as remote from the action as were previous generations of non-combatants; the folks who remained by the fireside awaiting news of loved ones during the Napoleonic Wars, the Crimean campaign or against the Zulu or Boer in southern Africa. This had partly to do with vastly improved communications, which permitted fighting men to write home, sending postcards and letters on a fairly regular basis. But it also enabled journalists to file newspaper reports – and photographers to accompany said dispatches with either prints or exposed film. All of these developments combined to reveal the true reality of warfare to those at home.

But there was, of course, another fundamental reason why civilians were now better informed about modern war: in the twentieth century those on the home front were often right on the front line.

British civilians were first subjected to total war in December 1914, when the German High Seas Fleet shelled Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby, an attack resulting in 137 fatalities and 592 casualties, many of whom were civilians, and then again when German aircraft attacked Dover.

These early raids were pinpricks. Though Dover Castle and the port were the main targets, the puny Taubes and Friedrichshafen floatplanes being unable to carry a significant bomb load did little damage, many of the bombs crashing into back gardens of private dwellings or harmlessly in open spaces. However, as The Times reported:

‘I try to forget you’, a First World War postcard.

One German airman on Christmas Day was more venturesome. Under cover of a dense fog, he eluded the watches on the coast as far as Sheerness, and there was lost sight of. He was next seen flying over Gravesend, and was, forced to turn, with a British-’biplane in pursuit, towards the North Sea, running the gauntlet of a heavy fire from anti-aircraft guns at different points.

It transpired that the pilot, Lieutenant von Prondzynski, ended up over Dover and, at a height of 5,000ft, leant over the padded edge of his cockpit combing and proceeded to heave his single bomb over the side, before releasing his grip and letting it fall. The pilot was about 400yd short of his target, Dover Castle, and succeeded in planting his bomb in the garden of the adjoining rectory. It made a crater about 4 or 5 ft deep, smashed some windows and knocked the gardener, Mr James Banks, out of the tree he was pruning.

But, even though these early air raids and the sinking of RMS Lusitania off Ireland in May 1915, which claimed 1,198 lives, were modest harbingers of what total war was to deliver in later years, enemy attacks on the British mainland still amounted to the deaths of only some 5,000 civilians during the First World War. Furthermore, when one compares the 1,500 British civilian deaths during the winter of 1917–18, the worst period for air raids with over 100 German attacks launched against the mainland, with the 750,000 British soldiers killed while on active service, the true impact of the war against the civilian populace is put in true and sobering perspective.

Worse, much was worse was to come, and during the Second World War a combination of conventional night bombing and, from June 1944, attacks by cruise (V1) and ballistic (V2) missiles amounted to over 60,000 civilian fatalities in Britain with thousands more survivors badly wounded or made homeless.

In both world wars, generally, the civilian populations at home suffered psychological rather than physical assaults.

First, of course, families were never sure of the whereabouts or indeed the mortal existence, of spouses, fathers or sons and this wearing uncertainty was a constant burden that played on the minds of adults at home or in the factories or children at school, anxious to hear that daddy was safe.

There was also constant unrelenting psychological pressure applied to non-combatants in more subtle, insidious ways. Men who had not joined up, either because they were retained at home in reserved occupations that were crucial to the war effort or because they were either too young, too old or medically unfit for military service carried a burden of guilt and the stigma of being a coward, possessing low moral fibre. Women, even if they were fully occupied managing a home, looking after children or perhaps an elderly or infirm relative, felt that they weren’t pulling their weight. To avoid such accusations of complacency many women somehow managed to survive long hours on the shop floor or munitions factory, or as so many did as early as 1915 by taking over jobs made vacant by men heading for the front, and driving trams and buses to keep society on the move.

‘It’s a puzzle for a woman’, a First World War postcard.

The National Registration Act 1939 established a National Register which began operating on 29 September 1939 and introduced a system of identity cards for adults and children with the requirement that they must be produced on demand or presented to a police station within 48 hours.

While they might not have faced the mortal dangers of the men at the front, civilians at home experienced their own kind of barrages – the daily, incessant bombardment of official notices telling them what to think and how to act. Whether it was one of the earliest British government communications designed to prick the consciences of so-called shirkers – a poster featuring an accusing John Bull, all top hat and tails and union flag waistcoat, stood in front of a row of new khaki-clad recruits, who, with outstretched arm and pointing finger, asks: ‘Who’s Absent? Is It You?’ or one from the Auxiliary Royal Air Force in the 1940s: ‘Castles of the Air. Man the Walls! – Join a Balloon Barrage Squadron’ – the message was clear. Everyone was in it together.

When war was declared in August 1914, in Britain, and indeed throughout Europe, there were street celebrations everywhere and a mood of optimism prevailed. Most people were sure the war would be over by Christmas. Asking for 100,000 volunteers, the government was both surprised and delighted to receive 750,000 new recruits in just a month.

Fought between 5 and 12 September 1914, the Battle of the Marne was viewed as a miracle because it resulted in an Allied victory against the German Army, and effectively ended the German push towards the outskirts of Paris. However, it required a counterattack of six French and one British field armies along the Marne River to persuade the enemy to retreat. The Germans weren’t pushed back too far and still occupied a chunk of France and all of Belgium. It was the beginning of four years of trench warfare on the Western Front. The early optimism at home soon dissolved and it became obvious that there would not be a quick victory.

The government could not hide the fact that many thousands of men had been killed or severely wounded. The return of wounded soldiers to London rail stations late at night did nothing to detract from the knowledge that casualties were horrendous.

‘Watch me make a fire-bucket out of ’is ’elmet’ – one of Bruce Bairnsfather’s many ‘Old Bill’ postcards from the First World War.

As if being witness to such tragedy as seeing the flower of their youth returning so severely damaged – at least the lucky ones returned, however mangled – those at home suffered other privations.

Inflation was one obvious consequence to which the isolation of total war and the unrestricted U-boat warfare subjected Britain’s economy. Poorer families soon discovered they could no longer afford the increased prices for basic food staples. Unlike during the Second World War when it was introduced in 1940, in the First World War, despite the shortages, rationing was only brought in by the government in February 1918 when a fixed allowance for sugar, meat, butter, jam and tea was introduced. British Summer Time was also established, providing more daylight working hours than before.

To ameliorate the effects of rationing The Win-The-War Cookery Bookv, ‘published for the food economy’, was available on bookshelves in 1918 priced at a very reasonable 2d. ‘Eat one pound less bread per week than you are eating now’ was emblazoned across the cover and inside a variety of cheap and easy recipes showed cooks how to supplement their diets. Recipes inside this very helpful and popular book included Surrey Stew, Fish Sausages, Parkin and Barley bread, incorporating all kinds of ingredients, except wheat. Rationing was beginning to take a hold but it worked and prevented marauding U-boats from starving Britain out of the war.

Other shortages at home had a dramatic effect on the troops in the front line. The shell crisis of 1915, which revealed that there simply were not enough munitions reaching the troops and, often, what shells did arrive turned out to be duds, encouraged Lloyd George as Minister of Munitions to be critical of Chief of Staff Lord Kitchener. The upshot was that Kitchener’s reputation never recovered and that Lloyd George assumed the role of Prime Minister after the fall of Asquith’s government, a direct result of the scandal. Another result of the increased demand for war munitions meant that factories worked round the clock and, for the first time, women took over jobs traditionally occupied by men.

‘Passed by Censor’ (received from HMS ship, no charge raised) envelope posted from HMS Folkestone, 1915.

Contents of the envelope above. The letter is from an officer aboard HMS Folkestone who, writing to his mother, not only asks her for ‘a couple of thin Aertex Cellular vests and pants, a couple of suits of thin pyjamas’, but goes on to explain that he has been mentioned in French despatches and even nominated for the Croix de Guerre! Such items are not only very collectable they also make an invaluable contribution to the historical record.

The combination of long hours and raw recruits to such a demanding and hazardous job inevitably meant that accidents happened – safety sometimes being compromised in place of speed and quantity of manufacture. The worst factory accident was at Silverton in the East End of London. On 19 January 1917, the munitions factory exploded and 69 people were killed and over 400 injured. Extensive damage was done to the area around the factory.

Passed in August 1914, the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) allowed the government to take over the coal mines, railways and shipping. Fortunately, the pragmatic endeavours of hardy Welshman Lloyd George enabled the government to work closely with the trade unions to avoid strikes. But with so many males leaving to join the army traditionalists had to accept that with a reduced workforce women were needed to do many jobs that had previously been the province of men.

Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), the ‘Suffragette’ movement in Britain that lobbied for the vote for women, earned new respect by limiting their militant actions in favour of supporting the war effort. As a result an amnesty was granted for WSPU prisoners and, in recognition for them keeping their side of the bargain, well before the war ended, on 6 February 1918, the Representation of the People Act was passed, enfranchising women over the age of 30. Women over 21 didn’t achieve the vote until 1928. But just as it had at the front, where the war threw working class lads alongside the middle class and even aristocrats, the twain never likely to ever have met in ‘civvie street’, the First World War had a massive effect on the role of people at home. Regarding women, especially, it both enfranchised them politically and socio-economically. Things would never be the same again.

This postcard, ‘Pals!’, showing a Tommy and his trusted mount appears all the more poignant following the success of Michael Morpurgo’s successful novel War Horse.

We will never know just how the ordinary civilians who had thrown themselves so wholeheartedly into supporting the war effort during the 1914–18 conflict felt when confronted by an official poster, aimed at men who had still managed to avoid the draft (conscription having been introduced with the Military Service Act of 1916), showing an enormous Zeppelin hovering above St Paul’s and featuring the headline: ‘It is far better to face the bullets than to be killed at home by a bomb. Join the army at once and help to stop an air raid. God Save the King.’ This poster might have finally encouraged malingerers to join up but I’m sure it didn’t do much for the morale of those rushing to catch a tram to the shell factory or, indeed, those women who were now driving them.

Surviving air raids during the First World War was largely left in the hands of providence, Air Raid Precautions not being officially organised until the late 1930s and based on the dread predictions of ‘experts’ who simply multiplied the effective bomb loads and high-explosive capacity of the First World War biplane bomber aircraft and their puny ordnance with the greatly increased capabilities of streamlined monoplanes with cavernous bomb bays. When the likelihood of poison gas and incendiaries being delivered alongside high-explosive bombs was added to the mix, it is not surprising that it wasn’t until long after 1918 that protection from such attacks was given official priority. Despite this, at the beginning of the Second World War those civilians without gardens into which they could bury corrugated iron Anderson shelters were forced to seek refuge in Underground stations, there being no official communal shelters available at the outbreak of hostilities.

During the First World War air-raid shelters were largely improvised. In Ramsgate, for example, caves and tunnels in the chalk cliffs were employed as shelters for several thousand people. They would be reused in the Second World War. That’s not to say there weren’t any purpose-built refuges to help civilians shelter from the aerial storm emanating from Zeppelins and Gothas. In Cleethorpes, Lincolnshire stands the oldest surviving air-raid shelter in Britain. It was constructed in April 1916 by Joseph Forrester, a chemist and local councillor, who built it from reinforced concrete with walls half a metre thick. The structure is 4m wide and 5m deep, and consists of a single room with two entrance lobbies. At some point, it was turned into a garage, and as such it survives, a legacy of the first strategic bombing campaign in history.

Delightful First World War postcard emphasising how much had changed in so little time as young men swapped civilian clothes for khaki.

The First World War was a revelation. Not just because of the extent of the slaughter but also because it was the first time civilians were exposed to the full fury of modern war and, crucially, because it saw the products of the Industrial Revolution and mass production turned to such an evil purpose as killing on a grand scale. Little did they, or the general officers who commanded them, know, but the Tommies who went over the top along the Somme in July 1916, facing rows of machine guns, were really steadily advancing towards unrestricted machine tools. They were walking towards malevolent lathes and milling machines which, spewing bullets in place of swarf, had had their guards removed and simply went about automatically killing and mutilating anyone who got in the way.

Lessons were learned from all this horror. One of them, of course, was to try to avoid repeating it. But, as we know, this was not to be. Fortunately, when, to the consternation of most right-thinking people, it became obvious that another war was unavoidable, the authorities had amassed enough data to enable them to provide civilian populations with the wherewithal, at least, to prepare themselves for a resumption of war on the home front.

This postcard makes exaggerated and cruel comment about those soldiers involved in logistics behind the front line enjoying far better rations than those at the front.

It is from the Second World War, and the build-up to that conflict, that the majority of official leaflets and posters were produced and survive to this day.

Although it didn’t exist during the First World War, the Air Raid Precautions (ARP) organisation which was created in Britain in 1924 almost links this conflict with the Second World War. It certainly charts the growing neurosis and fear that another war with its fleets of fast heavily armed bombers would lay cities to waste and signal the end of civilisation.

Italian Giulio Douhet published his influential Command of the Air in 1921 and his main argument supported the general fear that modern war planes would prove unassailable. In 1932 the Conservative Stanley Baldwin, then Lord President of the Council in Ramsey MacDonald’s National Government, famously used the phrase ‘The bomber will always get through’ in a speech before Parliament entitled ‘A Fear for the Future’. Baldwin argued that, regardless of air defences, sufficient bomber aircraft will always survive in sufficient numbers to press on their attacks and destroy cities.

In 1938 the Air Ministry predicted 65,000 casualties a week – in the first month of war the British government was expecting 1 million casualties, 3 million refugees and the majority of the London laid to waste. In the same year the Socialist biologist J.B.S. Haldane wrote A.R.P. (Air Raid Precautions) addressed to ‘the ordinary citizen, the sort of man and woman who is going to be killed if Britain is raided again from the air’. Haldane intended it to be a scientific counter argument to all the fantastical predictions prevailing at the time. With chapters entitled, ‘The Technique of Mass Murder’, ‘Keeping Bombers Away’, ‘The Government’s Precautionary Measures’, ‘Protection Against High Explosive Bombs’ and ‘Gas Proof Bags For Babies’, it made pretty chilling reading but the authorities quickly adopted many of its principles.

‘Some Things You Should Know If War Should Come’, Public Information Leaflet No. 1 issued as early as July 1939.

Home Secretary Samuel Hoare was naturally closely involved with the progress of government Air Raid Precautions in Britain. Answering a question about the nation’s defences against enemy air attack in a debate in the House of Commons in May 1938, he said:

By the Regulations made under the Air-Raid Precautions Act, the duty of providing such shelters as are necessary is placed upon the local authorities. My hon. Friend is aware that I have asked authorities to conduct a survey of the problem in their areas, so that they may ascertain the number of persons likely to be exposed in the streets and the numbers who are in houses in which additional protection cannot be given. I have also asked them to make a survey of the accommodation available in their area which, with some adaptation in peace-time, could be used as shelter accommodation in war-time, and I have more recently indicated the need of planning for a deep trench system in all open spaces in or near centres of population. When plans on these lines have been completed it will be possible for the local authority to see whether it is necessary to provide any specially constructed shelter accommodation.

Stanley Baldwin had famously claimed that the night bomber would always get through. The first thing most people feared was their homes being razed by enemy bombs.

Officially recommended by the Air Raid Defence League, established early in 1939 to bring all ARP workers together into one organisation, this ARP Practical Guide sought to equip householders with all the information they would require to cope with air attack.

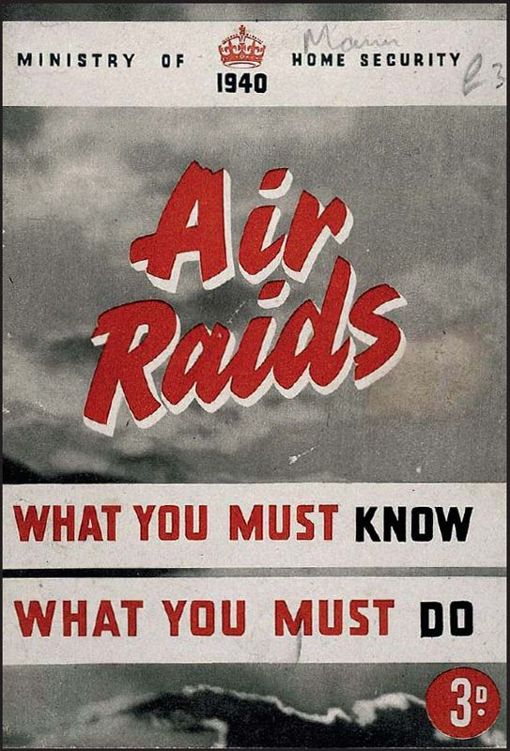

‘Air Raids. What You Must Know and What You Must Do’ was issued in 1940 by the Ministry for Home Security.

Dating from 1 October 1938, the inaugural edition of Sir Edward Hulton’s pioneering Picture Post magazine. First editions of any periodical command the highest prices among collectors.

A trio of petrol coupons dating from 1940. Petrol was the first commodity to be rationed upon the outbreak of war in September 1939.

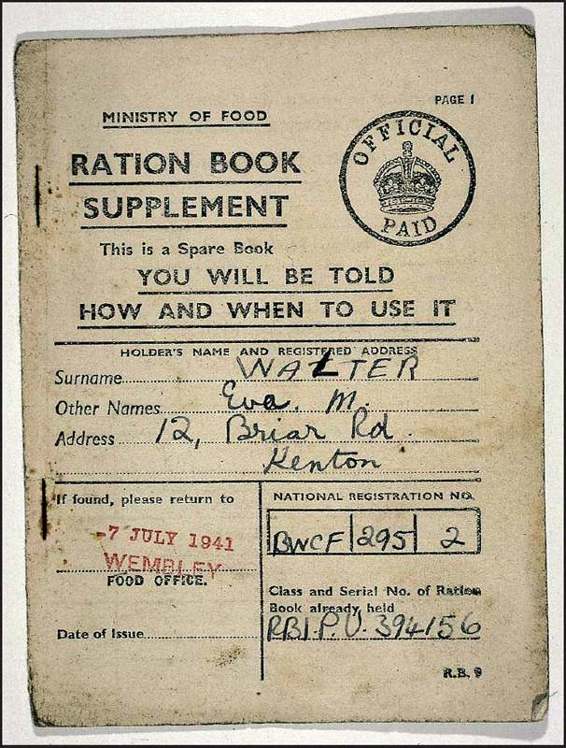

Ration Book Supplement, the householder’s spare ration book, dating from 1941.

Soon afterward the government published a booklet entitled The Protection of Your Home Against Air Raids. It was posted to every citizen and additional copies could be purchased for only a penny. Hoare penned the introduction headed ‘Why this book has been sent to you’.

If this country were ever at war the target of the enemy’s bombers would be the staunchness of the people at home. We all hope and work to prevent war but, while there is a risk of it, we cannot afford to neglect the duty of preparing ourselves and the county for such an emergency. This book is being sent out to help each householder to realise what he can do, if the need arises, to make his home and his household more safe against air attack.

The Home office is working with the local authorities in preparing schemes for the protection of the civil population during an attack, but it is impossible to devise a scheme that will cover everybody unless each home and family play their part in doing what they can for themselves. In this duty to themselves they must count upon the help and advice of those who have undertaken the duty of advice and instruction.

If the emergency comes the country will look for her safety not only to her sailors and soldiers and airmen, but also to the organised courage and foresight of every household. It is for the volunteers in the air raid precautions services to help every household for this purpose, and in sending out this book I ask for their help.

Section 1 of this useful but rather chilling little booklet was entitled ‘Things To Do Now’. It contained advice about preparing a safe refuge in your home, ensuring that the blackout was observed (‘In time of war all buildings will have to be completely darkened at night …’), tips on how to tackle fires and small incendiary bombs and how to deal with the new respirators (gas masks) that were about to be distributed. The authors were particularly concerned that householders looked after these contraptions which, they said had been:

Designed for you by Government experts and, though simple to look at, exhaustive tests have shown it to be highly efficient.

When not wearing the respirator, remember these rules:

1. Do not expose it to strong light or heat.

2. Do not let it get wet.

3. Do not scratch or bend the window.

4. Do not carry or hang the respirator by the straps.

The threat of chemicals (poison gas) being delivered from enemy aircraft hung like a sword of Damocles above the heads of British civilians throughout the Second World War in the same way that the ‘A-bomb’ threatened subsequent generations during the cold war.

To help enforce these regulations and offer advice about the best ways to protect their homes from air attack, civilians turned to the growing band of ARP Wardens who patrolled the blacked out streets. ARP Wardens were trained in basic fire-fighting and first aid, and could keep an emergency situation under control until the official rescue services arrived. In addition they helped to police areas suffering bomb damage and assisted bombed-out householders.

Stirring ‘Your Britain Fight For It Now’ poster by Frank Newbould who was assistant to the War Office’s official war artist for posters, Abram Games.

‘Grow Your Own Food’ another poster from the genius that was Abram Games.

Nearly a million and a half volunteer wardens supported Air Raid Precautions during the war and almost all of them were unpaid part-time volunteers who also held day-time jobs. Far from being the grumpy little Hitlers portrayed in popular comedy, for ever bellowing ‘Put That Light Out!’ whenever they spotted a chink of light escaping from a living room window, they were really the unsung heroes of the home front. Initially, wardens were expected to be on duty three nights a week, but the frequency of their shifts increased as night bombing became more frequent.

During the Air Estimates debate in the House of Commons on 1 August 1939 British politicians reviewed the progress in Civil Defence, especially the provision of shelters for the civilian population, especially those who were without the space to erect Anderson shelters. Interestingly, part of the debate involved criticism of these constructions, Robert Boothby arguing that they were fragile and leaked.

The subsequent Hailey Conference decided that providing deep shelters would lead to workers staying underground rather than staying on the surface and working when the all clear had been signalled. However, this policy was reversed in 1940 when most of the London Underground network was opened for use as overnight shelters and the construction of specialised communal deep shelters began.

The National Registration Act of 1939 established a National Register and everyone, including children, had to carry an identity (ID) card at all times to show who they were and where they lived. The identity card gave the owner’s name and address, including changes of address. Each person was allocated a National Registration number and this was written in the top right-hand corner on the inside of the card. The local registration office stamped the card to make it valid. ID cards had to be produced on demand or presented to a police station within 48 hours.

Collectors should note that the earliest, buff-coloured cards are the rarest. Blue ID cards were introduced in 1943 and government officials had green ID cards. Members of the armed services had their own, unique identification cards. Children under 16 were issued with identity cards but they were to be kept by their parents. Identification was necessary if families got separated from one another or their house was bombed, and if people were injured or killed.

A further Abram Games classic – a famous recruitment poster for the ATS.

On the actual outbreak of war a small, blue, eight-page roll-fold leaflet entitled ‘War Emergency Information and Instructions’ was distributed to British householders. The text on the cover set the tone from the start: ‘Pay no attention to rumours. Official news will be given in the papers and over the wireless. Listen carefully to all broadcast instructions and be ready to note them down.’ The leaflet contained concise details about what to do regarding identity labels, during air raids and about the closing of cinemas, theatres and places of entertainment. It told readers about the need for evacuation from certain areas likely to be the scene of armed combat, about lighting restrictions, fire precautions and how to deal with incendiaries and about travelling on the road and railways. The authorities wanted to avoid arterial highways being blocked by civilian refugees – something they thought greatly aided the progress of blitzkrieg.

You must not drive or cycle at night unless your lights are dimmed and screened in accordance with the regulations. You can get a leaflet giving details of these restrictions from any police station. No car or cycle will be allowed on the road at night until the lights have been dimmed in the way described in the leaflet. If you have a car use it very sparingly because the supply of petrol will be rationed immediately.

Citizens were told that from the first day of war day schools would be closed for a week and would only reopen upon the discretion of local authorities. They were also advised not to use the telephone unless there was an emergency.

A speedy telephone service is vital for defence. You may be causing delay to very urgent calls. To meet the needs of defence operations it may be necessary to disconnect some telephones temporarily. Do not telegraph unless it is very urgent. Telegraph offices will also be dealing with official messages and your message may delay important telegrams.

There was also information for pensioners about the need to keep their pension and allowance books with them, especially if they moved away from home, in order to draw their pension. Similarly, those in receipt of other benefits, such as widows, orphans and those drawing Great War disability payments were advised to keep their papers in order so that they could ‘cash the orders in them on the proper dates at a Post Office in their own district’.

People were told not to worry about food supplies because stocks of foodstuffs in the country were sufficient. However, the leaflet did allude to rationing:

In order to ensure that stocks are distributed fairly and to the best advantage the Government are bringing into operation the plans for the organisation of food supplies which have already been prepared in collaboration with the food trades. Steps have been taken to prevent any sudden rise in the price, or the holding up of supplies. For the time being you should continue to obtain supplies from your usual shops. You should limit your purchases to the quantities which you normally require.

Section 15 summarised the general instructions and was intended to reassure a naturally very nervous populations:

Carry your gas mask with you always.

Do not allow your children to run about the streets.

Avoid waste of any kind whether of food, water, electricity or gas.

Obey promptly any instructions given you by the police. The special constables, the air raid wardens, or any other authorised persons and be ready to give them any assistance for which they ask you.

All of the above is quite chilling. This was reality. Goodness knows what people thought when they considered their futures. Certainly, what they did know was that in the last war Britain had suffered nearly 1 million casualties. Since then technology had developed exponentially. Just what the ‘lights of perverted science’, to paraphrase a later speech by Winston Churchill, might be able to inflict on cowering civilians now that aeroplanes flew higher and faster and could carry much larger bomb loads than ever before, was doubtless something that kept many people awake at night.

The authorities were, of course, aware of all this and were sensitive to the people’s insecurities. In an effort to reassure the electorate the last couple of paragraphs of the War Emergency instruction leaflet were printed in block capitals:

DO NOT TAKE TOO MUCH NOTICE OF NOISE IN AN AIR RAID. MUCH OF IT WILL BE THE NOISE OF OUR OWN GUNS DEALING WITH THE RAIDERS.

KEEP A GOOD HEART: WE ARE GOING TO WIN THROUGH.

Although food rationing had first been introduced to Britain in 1918, when Germany’s U-boat campaign began to have a dramatic effect on the nation’s imports, it was more widely applied and lasted much longer when introduced in January 1940, during the Second World War. With Britain depending on imports for 70 per cent of its food each year this was hardly surprising.

To buy rationed items, each person had to register at chosen shops, and was then provided with a ration book containing coupons. The shopkeeper was provided with enough food for registered customers. Customers had to take ration books with them when shopping, so the relevant coupon or coupons could be cancelled.

Imagine the shock of receiving a leaflet such as ‘Beating the Invader’ through your letterbox today! ‘Stand Firm!’ and ‘Carry On!’ urged Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

The first commodity to be rationed was petrol, immediately war began in September 1939. In January 1940 this was followed by the rationing of bacon, butter and sugar and subsequently by meat, tea, jam, biscuits, breakfast cereals, cheese, eggs, lard, milk, canned and dried fruit and, by 1942, almost every foodstuff except vegetables and bread.

To encourage citizens to supplement their diets by growing their own food the government initiated the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign and urged the public to use any spare land available to grow vegetables – parks and even golf courses were turned over to the common good.

Mabel Lucie Attwell’s career as an illustrator began at the turn of the twentieth century and she is rightly famous for her illustrative work in Alice in Wonderland, The Water Babies and Peter Pan. She also illustrated dozens of postcards during both world wars and they are now very collectable. The two seen here date from the Second World War period.

The government also distributed 10,000,000 leaflets showing householders how to turn their lawns and flower beds into productive agricultural land and further encouraged people to keep an allotment. The campaign was so successful that it is thought to have been the catalyst for nearly 1,500,000 allotments. It wasn’t just about cabbage and potatoes, civilians were also encouraged to keep wildlife. Most who did husbanded chickens, ducks and rabbits, but others kept goats and even pigs, which were very popular because they thrived on kitchen waste. ‘Pig Clubs’ were started for collecting food leftovers in big bins to feed the pigs.

Children were especially entertained by Doctor Carrot and Potato Pete, two cartoon characters who featured on ‘Dig for Victory’ posters, although perhaps they were less enamoured with Woolton pie, the dish made entirely from vegetables which was popularised by Lord Woolton, the Minister of Food in 1940. Neither, I’m sure, were they great fans of ‘curried carrot’ or ‘carrotade’ – a sweetened drink based on, you guessed it, the humble carrot.

By 1943, allotments in Britain produced over a million tonnes of vegetables.

At the outbreak of the Second World War all males aged between 18 and 41 were asked to register so that the authorities could direct any men not engaged in vital war work, in ‘reserved occupations’, as required into the army, navy or air force. By February 1942 more than 3,500,000 men had been called up and some 250,000 women wore the uniform of the Women’s Auxiliary Services – the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) or the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS).

Ernest Bevin, co-founder and general secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers’ Union from 1922, had in 1940 been made Minister of Labour in Churchill’s war-time coalition government. Bevin squeezed the most out of the British labour supply, massively reinforcing the workforce with a minimum of strikes and disruption.

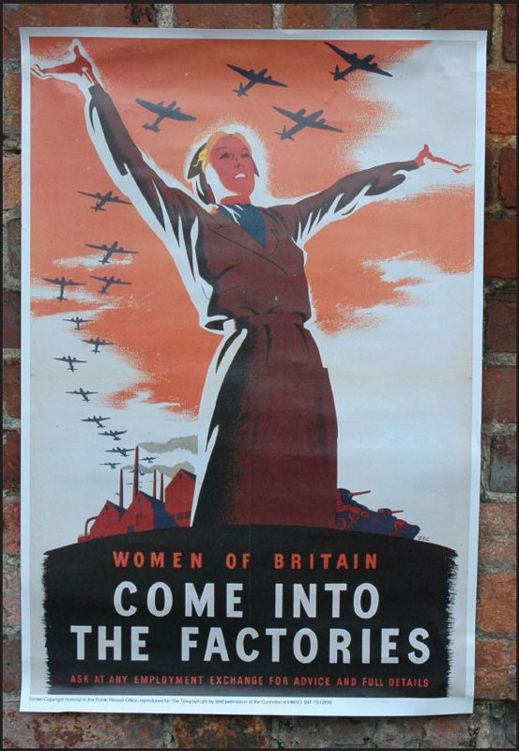

‘Come into the Factories’ poster by Philip Zec, encouraging women into war industry for the good of the nation.

‘Back Them Up’ by Ron Jobson. After leaving Camberwell School of Art, where he had won a scholarship aged 13, he joined the War Artists and Illustrators Studio. After the war Jobson worked in publishing advertising and illustrated for clients including one that’s dear to my heart, Airfix.

‘Dig on for Victory’ poster by Peter Fraser.

‘Let Us Go Forward Together’, the iconic Ministry of Information photo-montage poster featuring Winston Churchill.

‘The Life-Line is Firm Thanks to the Merchant Navy’, a 1942 poster by Charles Woods.

‘Keep Mum – She’s Not So Dumb!’ by Harold Forster. Interestingly, this was in the same vein as the previous ‘Be Like Dad, Keep Mum’ poster which outraged Labour MP Dr Edith Summerskill, a feminist and one of the founders of the Women’s Home Defence Unit, where women who could shoot, wanted to defend their homes but were ineligible for the Home Guard turned to after the Fall of France in 1940.

Bevin was the prime mover behind the Registration of Boys and Girls Order, 1941 and posters detailing the provisions of this new Act of Parliament were posted in public places for all to see. It read:

Notice to boys born between 1st February, 1925 and 28th February, 1926, both dates inclusive. Requirement to register on 28th February, 1942

Boys who live more than six miles from a Ministry of Labour and National Service Office, or suffer from some permanent incapacity, may fill up a registration form on the day prescribed and post it to a Ministry of Labour and National Service Office. Forms for this purpose may be obtained on request from a Ministry of Labour and National Service office.

‘The Navy Thanks You’ poster by Pat Keely, a prolific posterist who also produced work for London Transport, Southern Railway and the Post Office.

Penalties

Any boy who fails to register in accordance with the foregoing requirements is liable, on summary conviction, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three months or to a fine not exceeding £100 or both. There are heavier penalties on conviction on indictment.

Despite their wishes, perhaps, for a job in the armed services, the Ministry of Labour’s official urgings saw nearly 48,000 so-called Bevin Boys, chosen at random, perform vital but largely unrecognised service in Britain’s coal mines. More than 10 per cent of those young men conscripted were to see service at the coal face rather than on the battlefield. It is, however, an undoubted fact that such war service was every bit as vital to the war effort as those young men aged between 18 and 25 who went to sea, wore khaki in the British Army or joined the RAF.

From 1938 onwards British civilians had been inundated with a deluge of instructions about almost anything. What to do in the event of air raids, how to participate in the war effort and even how to enjoy themselves. To keep an eye on their reactions and gauge public morale in general the government tapped into an existing organisation, Mass Observation (MO), established in 1937, by Tom Harrisson, Humphrey Jennings and Charles Madge – ‘a project to study the everyday lives of ordinary people in Britain’, ‘an anthropology of ourselves’ (see Chapter 1). In gathering its research, MO more or less spied on the average man and woman in the street.

‘In Your Money Lies Victory. We civilians have as important part to play in the war as the Navy, the Army or the Air Force. It is for us to provide them with money. Purchase saving certificates.’, extract from this leaflet issued by the Post Office Savings Bank.

Collecting original letters together with any official documents such as log books like the examples shown here belonging to Flying Officer J.R. Whelan, a Blenheim pilot with 18 Squadron (BEF) in France, adds gravitas to any anthology.

During the Second World War Balcombe Place became the headquarters of the Women’s Land Army. Having been an active supporter of the Suffragette movement before and during the First World War, in the Second World War its owner, Lady Gertrude Mary Denman, was Director of the Women’s Land Army.

‘War Weapons More Money’. For each belligerent nation the cost of modern warfare proved prohibitive and national funds needed to be supplemented by contributions from the body publics. War savings and war bonds schemes abounded and many were designed by the cream of the commercial art industry, as these two leaflets so ably illustrate. Issued by the Post Office Savings Bank.

Professor Dorothy Sheridan MBE has worked with the Mass Observation papers since 1974, both as archivist and then Director of the Archive at the University of Sussex. I had the good fortune to meet her when I used the archive while researching my book A Nation Alone in the late 1980s. Professor Sheridan has also written a number of excellent anthologies about the organisation. In one of them, Wartime Women, she collated numerous reports which reveal precisely how women, the great majority of whom endured hardships such as rationing and the terrifying uncertainty of coping with night bombing, made sense of the disadvantages they now faced.

Norfolk resident Muriel Green worked at her family’s garage in 1940 and kept a record throughout which she shared with Mass Observation and upon which, along with hundreds of other returned questionnaires and essay submissions, the organisation was able to assess the true state of British morale and consequently help the government adjust policies which might affect the well-being of the civil population.

Ms Green’s entry for 31 January is particularly revealing and provides us with an excellent idea of just how tough life was during the first winter of the war:

We have run out of coal. We have no garage fire and are burning wood in the house. We have had no meat this week, as the butcher has not come. He had hardly any last week. A customer bought us two rabbits on Monday so we are not starving, but lots of people, my great aunt among them, have had no meat. Ever so many have had no coal all the week. Arnold shot us two pigeons in the wood opposite.

And families were left in no doubt about whose future they were fighting and saving for.

The First World War had brought about massive changes to the social fabric of Great Britain and women had assumed a much more important role within society. While this period could hardly be said to have seen women’s status change in a massive way, the impact of the Suffragette struggle and that organisation’s acquiescence to government appeals for calm and co-operation during the conflict did garner some results and this period could be seen as the birth of women’s liberation. Similar social evolution occurred during the Second World War, with women not just taking over some of the roles traditionally held by men in the workplace, for example at the lathe and even operating forges, but also adopting habits that were previously the preserve of menfolk, such as drinking in pubs.

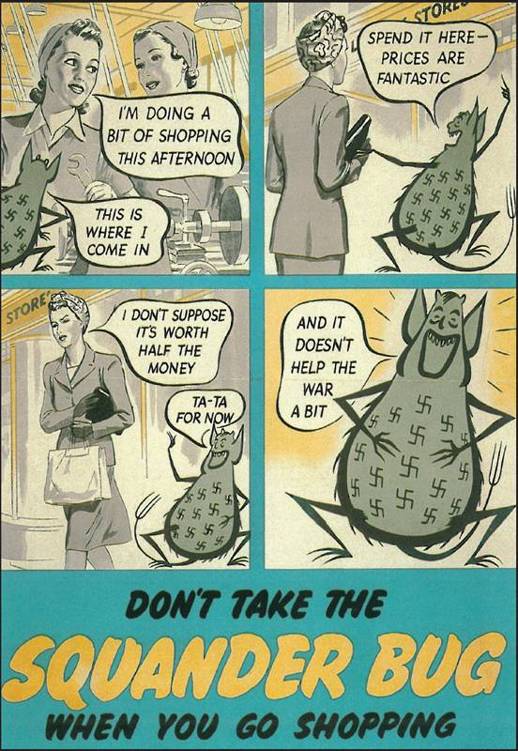

Freelance illustrator Phillip Boydell allegedly created the famous ‘Squander Bug’ while in bed with influenza.

Mass Observation’s archives are full of numerous recordings of discussions with and about women and public houses. One pub landlord, from Fulham in London, had this to say:

Yes, the war has made a great deal of difference; I don’t mind girls drinking in the bar alone or otherwise. Usually when they come in alone, they don’t go out alone, but who am I to criticise – my job is to sell the liquor and be pleasant to customers, not to be nosey about their coming and goings.

With the announcement of Hitler’s death on 1 May 1945, it was obvious that the war in Europe was about to come to an end. On 7 May the Mass Observation entry of Amy Briggs, a nurse in Leeds, encapsulated the general feeling (Victory in Europe, or VE, Day, a public holiday, would take place on 8 May):

What a day! It hardly seems possible that it was only this morning that I got up! There has been a steady crescendo of excitement, and the lack of any official announcement only added to the chaotic conditions. At the 3p.m. news broadcast, there was a report from the German radio that they surrendered unconditionally this morning, but SHAEF [Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force] has said nothing. Now this really is something; the office is buzzing with excited, facetious chatter. A woman clerk comes in and we tell her the news: ‘Six years I’ve sat in this chair waiting to hear that, and now, when it comes, I have to be out of the room!’

British citizens weren’t only expected to make do with less they were also expected to reuse and repair what they already had. When clothes rationing was introduced in May 1941, ration books contained only sixty-six clothing coupons and they had to last for a year. Although people still had to pay for clothes, one dress also required eleven coupons and the right number of coupons had to be handed over each time a garment was purchased.

In 1943 the MOI published a handy little booklet, Make Do and Mend, which suggested a whole variety of ways individuals could spruce up their wardrobes and add new life to existing, often tired and unfashionable, garments.

With rationing severely restricting the availability of new fabrics, those who wanted a new outfit simply had to learn how to ‘Make Do and Mend’ with whatever materials they could find at home. This famous poster was designed by Donia Nachshen, who was from a Jewish family and born in Russia. She studied at the Slade School of Fine Arts, London. Nachshen was a book illustrator for publisher John Lane and also designed posters for the Post Office.

Hugh Dalton, the Labour Party economist who served in Churchill’s wartime coalition Cabinet first as Minister of Economic Warfare from 1940–2 when he established the Special Operations Executive, and was later a member of the executive committee of the Political Warfare Executive, was, by 1943 President of the Board of Trade and wrote the forward to Make Do and Mend:

First I would like to thank you all for the way in which you accepted clothes rationing. You know how it has saved much needed shipping space, manpower and materials, and so assisted our war effort.

The Board of Trade Make Do and Mend campaign is intended to help you to get the last possible ounce of wear out of all your clothes and household things. This booklet is part of that campaign, and deals chiefly with clothes and household linen.

No doubt there are as many ways of patching or darning as there are of cooking potatoes. Even if we ran to several large volumes, we could not say all there is to say about storing, cleaning, pressing, destroying moths, mending and renovating clothes and household linen.

But the hints here will, I hope, prove useful. They have all been tested and approved by the Board of Trade Make Do and Mend Advisory Panel, a body of practical people, mostly women, for whose help in preparing this booklet I am most grateful.

Though sometimes patronising and full of sexist gender stereotyping (‘Clothes have simply got to last longer than they used to, but only the careful women can make them last well.’), the Make Do and Mend booklet was full of good intentions. It helped households deal with a range of vexing issues including ‘The Moth Menace’, ‘Binding for Frayed Edges’, ‘Worn Underarms’, ‘Too-short Blouses’ and ‘Too-tight Underwear’.

The CC41 utility label, meaning ‘Controlled Commodity’, was designed by Reginald Shipp, a London-based commercial artist whom The Board of Trade awarded a personal prize of £5. His logo appeared on clothing from 1942 and lasted, amazingly, until 1952. Clothes bearing the CC41 label were cut to avoid wasting cloth so pleats, embroidery and unnecessary folds were a definite no-go. There were no turn-ups on trousers either, an item of clothing which the Make Do and Mend booklet addressed thus: ‘Trousers. Fold carefully in their proper creases every night. Sew a piece of tape or odd piece of material or leather inside the bottom of each leg where the shoe rubs, to prevent it wearing thin.’ In fact Hansard records that during a debate in the House of Commons on 16 March 1943, the subject of trouser turn-ups, or rather the lack of them, was actually debated in government. Mr Edmund Radford, the MP for Rusholme in Manchester, asked Hugh Dalton, President of the Board of Trade, if:

In view of the wide dissatisfaction with the austerity clothes regulations, whether he will consider the advisability of conferring with practical representatives of the bespoke tailoring trade, as distinct from the manufacturing interests, with a view to amending the regulations, thereby making them more practical and thus removing the serious irritation they are causing to professional and business men in particular?

Despite numerous more pressing issues a Cabinet minister was bound to deal with, Hugh Dalton found time to answer Mr Radford’s question with careful consideration:

These regulations were introduced in May, 1942, after consultation with the trade. Their purpose was to effect a substantial economy in shipping space, materials and labour, and in this they have succeeded. The need for such economies is even more urgent now than it was ten months ago, and I could not agree to any amendment of these regulations which would diminish their effectiveness in this respect. Subject to this condition, I shall be glad to consider any representations which the trade may wish to make.

Radford then thanked Dalton for being prepared to receive representatives of the bespoke tailoring trade and asked him whether the austerity regulations were originally intended to apply only to utility clothing and not to non-utility: ‘Is it not a fact that trousers with turn-ups wear longer than non-turn-ups?’ Dalton’s answer was immediate but revealed not a little of the irritation he must have felt given that, although Britain could at last see light at the end of the tunnel having won the Second El Alamein the previous November, there was still a long way to go.

No, Sir. There was never any limitation of these regulations for utility clothing. Turn-ups are a very debatable subject. I do not accept the view of my hon. Friend, and I would like to let him know that on the turn-ups regulations alone millions of square feet of cloth have already been saved. The Services have no turn-ups, nor do many hon. Members of this House who take particular care of their tailoring.

This leaflet explained that by following a plan householders could cultivate and enjoy fresh vegetables all year round.

Together with the numerous official publications raining down on the average citizen either from billboards or received in the post, as well as the covert snooping of Mass Observation pollsters during the Second World War, both twentieth-century conflicts saw a popular increase in kinds of literature driven by public desire and interest rather than official nannying.

Apparently, the first postcard can be dated to Austria in 1869 and they arrived in Britain a year later. Presumably this wasn’t receipt of the one posted in Austria!

It was the Paris Exhibition of 1889, held on the hundredth anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, which really saw this message of communication take off in a big way. With nearly 6,500,000 visitors attending in just 6 months one can imagine the number of stories people who went there wanted to share, and they did this via the postcard. In 1894 Britain’s Post Office finally approved of the private publication of postcards and a cheaper,? d stamp was introduced specifically for such missives. The divided back postcard, with clearly defined areas for address and message was introduced in 1902.

There was a lighter side to Air Raid Precautions, as this postcard demonstrates.

During the Edwardian period postcards became a veritable craze, not just because people found them a useful way of keeping in touch – the email of the time, but because they enjoyed building collections. In fact, postcard albums really replaced photographic albums in popularity. Consequently, when war was declared in 1914 and thousands of British troops marched off to France, postcards proved the ideal way for them to keep in touch.

Embroidered silk postcards, ‘silks’, proved particularly popular at this time. Local French and Belgian women embroidered different motifs onto strips of silk mesh which were sent to factories for cutting and mounting on postcards. These motifs often featured sentimental messages of love and adoration but also, equally often, regimental badges and colours.

Postcards were often published as a series, perhaps each separate card bearing a single verse from a popular song of the time. Many featured faithful spouses longingly waiting for the return of their men folk. Some depicted wives stoically urging their men on to final victory. On the other hand some revealed just what the men were fighting for and revealed what might happen if the barbaric Hun arrived in Britain and rampaged through isolated homesteads, devoid of men to protect the vulnerable women and children living there. Some inevitably depicted the alleged barbarities inflicted on the innocent people of Belgium by advancing German troops. Many simply showed the devastation the war had wrought on the towns and villages of Flanders.

Publishers like Raphael Tuck and Charles Rose printed new postcards by the thousand and supported the efforts of artists such as Louis Wain, Donald McGill, Tom Browne, James Bamforth and Mabel Lucie Attwell. However, perhaps the most famous artist of the First World War period is Bruce Bairnsfather, who before the war had illustrated advertising posters for products such as Lipton Tea, Players Tobacco and Beechams powders. During the war Bairnsfather served as an officer in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment alongside such people such as Captain Bernard Montgomery and Lieutenant A.A. Milne.

Bairnsfather had actually taken part in the famously unofficial Christmas truce of 1914 and was subsequently censured for his actions, narrowly avoiding court martial. However, it is for the drawings of life on the Western Front, and in particular the creation of that veteran soldier Old Bill, published from 1915 in the Bystander magazine as ‘Fragments from France’, for which he will be forever remembered. Postcards featuring Old Bill and surviving vintage copies of ‘Fragments from France’ now command high prices which the hundredth anniversary of the war have only pushed even higher.

Hitler eavesdropping in one of Cyril Kenneth Bird’s (Fougasse) famous ‘Careless Talk Cost Lives’ posters. The artist was seriously injured at the Battle of Gallipoli during the First World War but had a very successful career with the British press and with magazines, including the Graphic and Tatler

‘Let’s Go – Wings For Victory’ poster from 1943.

During the Second World War many of the artists and illustrators who had established themselves some twenty years earlier found a ready market for their work once again, Mabel Lucie Attwell notably among them. Indeed, her beautifully illustrated postcards now command some of the highest prices.

In relative terms, certainly in the first few years of the Second World War, far fewer British men were on active service overseas than had been the case during the 1914–18 conflict. Other than French postcards mailed by the men of the BEF during the winter of 1939/40 and images of the Sphinx, Pyramids, the port of Alexandria and Cairo street scenes from soldiers in the Middle East (the beleaguered troops in Burma had rather more on their mind than postcards), there aren’t as many vintage examples from this period as there are surviving from the Great War.

However, Kenneth Clark and his colleagues on the War Artists Advisory Committee (WAAC) ensured that art remained a priority at home. Clark also won the blessing of the trustees of the National Gallery for a series of free public concerts by Dame Myra Hess who organised what would turn out to be some 1,700 lunchtime concerts spanning a period of 6 years, starting during the London Blitz. Clark even managed to persuade the Home Office and Ministry of Works to grant the concerts dispensation from the ban on public gatherings. ‘The sooner we can start the better’, he wrote, ‘As this is the period when people are beginning to feel the want of nourishment for mind and spirit and it would be a great thing for the National Gallery to give a lead.’

The WAAC was also the prime mover behind a painting which, like Dame Myra’s musical talents, was also exhibited at the National Gallery. Charles Ernest Cundall’s epically large canvas Withdrawal from Dunkirk was painted in June 1940, barely a month after the famous maritime evacuation of ¼ million men of the BEF. Cundall’s painting rapidly become a popular propaganda image of British endurance and like so many other famous images became a popular subject for postcard publishers.

At the time of writing a series of articles in the press revealed that British postcards had an eager following in Nazi Germany, where they were used to help Hitler plan his proposed invasion, Operation Sea Lion, and referred to by Luftwaffe planners selecting high-profile targets in the British Isles. The Daily Mail Online reported the following:

This little booklet (front and back cover shown) explained how the United States was sending men and materials to help Britain in time to launch a concerted second front in Europe.

A collection of English seaside postcards collected by German tourists before the Second World War confiscated by Hitler and used to plan the Nazi invasion of Britain have recently been unearthed. The black and white images of coastal beauty spots were originally taken home by families as mementoes of their visit to the island. After the outbreak of war in 1939 the German military machine collected thousands of the postcards as Adolf Hitler plotted to conquer Britain.

Together with postcards, the find also included a selection of booklets full of specific details which might be of help to the invader. Max Haslar, of London-based Dreweatts auctioneers who were preparing to sell the collection, said (as quoted in the Daily Mail Online):

These briefing booklets were printed in preparation for Operation Sealion, the German invasion of Britain which thankfully never came to pass. This is probably the most extensive collection of these booklets to come up at auction. They were used by the German military and the Luftwaffe during the war and illustrate places and road junctions in the UK that German intelligence thought should be attacked as part of the British invasion.

Certainly it is known that from April 1942, starting with Exeter, Luftwaffe planners used copies of Germany’s famous Baedeker travel guide to plan a series of Vergeltungsangriffe (retaliatory attacks) on English cities in response to the bombing of the German city of Lübeck the previous month. The so-called ‘Baedeker Blitz’ would see raids on Norwich, Exeter, Bath, York and Canterbury, leaving 1,637 civilians dead, 1,760 injured and more than 50,000 homes destroyed.

Whether a miner at the coal face, a fire-watcher on the lookout for stray incendiaries or a housewife running a rationed household – everyone on the home front was in it together. As these five cards so ably put it: ‘To Blast the hopes of Hitler! It all depends on me.’

Collecting cigarette cards was as popular during the Second World War as postcard collecting had been during the First World War. Like vintage postcards, cigarette cards now command high prices. And, like postcards, their value is higher if they are in good condition and not stuck into albums. However, unlike with postcards, the major publishers of cigarette cards produced albums specifically for collectors to paste their cards into. Although each card had a description about its illustrated face specifically printed on the card’s reverse, this was repeated in the album, immediately below the position where the individual card was to be stuck, which naturally encouraged owners to glue their cards into position. Although the cards, usually published in sets of fifty, looked much better when placed in position in their specific albums and were naturally much easier to study, they have a far higher value if they are mint and loose.

Manufacturers including John Player and Sons, Ardath, W.A. & A.C. Churchman, Gallaher, W.D. and H.O. Wills among others published sets with titles such as ‘Life in the Royal Navy’, ‘It All Depends on Me’, ‘The RAF at War’, ‘Army Badges’, ‘Air-Raid Precautions’, ‘Aircraft of the Royal Air Force’ and ‘Life in the Services’, all of which proved very popular and encouraged purchasers greedily to smoke successive packs of cigarettes in order to get that last elusive card and complete their sets.

Information printed on the backs of cigarette cards was obviously not particularly up to date and showed wartime developments in pretty generic terms. There were, of course, the newspapers, and although the MOI, housed in the University of London Senate House and upon which Orwell based the Ministry of Truth in Nineteen-Eighty-Four, had the power to censor the press it rarely did. The Home Office could fall back on the Emergency Powers Act, which made it illegal to disseminate information that might harm operational security, but, again, this stricture was rarely enforced as, after the event, the damage would probably already have been done.

So, newspapers were largely left alone. However, as broadsheets were only read by the cognoscenti, press articles didn’t have a massive readership. With so many people visiting the cinema on a regular basis, the best method for conveying news, and official propaganda, was via the newsreels, which were a feature of every programme.

Women might not be able to operate eight Browning machine guns but they could ‘Serve in the WAAF with the Men who Fly’. In fact dozens of women pilots were in command of unarmed fighters and bombers in the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA).

Saving and recycling waste paper isn’t an entirely modern innovation, and sensible householders where actively engaged in reprocessing more than seventy years ago.

Initially, short documentaries were made and filmed by the GPO film unit, a subdivision of the UK General Post Office. This organisation was established in 1933 and took over the responsibilities of the Empire Marketing Board Film Unit, which had been set up in the mid-1920s by the Colonial Secretary Leo Amery to promote intra-Empire trade with its slogan ‘Buy Empire’. At first the GPO Film unit produced documentary films mainly related to the activities of its parent, the GPO.

One of its most famous films is Harry Watt’s and Basil Wright’s 1936 production Night Mail, which features music by Benjamin Britten and poetry by W.H. Auden.

In 1940 the GPO Film Unit became the Crown Film Unit, under the control of the Ministry of Information. The Crown Film Unit produced a mixture of information heavy shorts as well as longer documentary films and many of what we now know as docudramas. Its audience was not restricted to the general public in Britain but to those living abroad. In fact, the Crown Film Unit continued to produce films, as part of the Central Office of Information (COI), until it was disbanded in 1952.

Those unable to leave their home and contribute in National Service as factory workers or fire-watchers, for example, could still do useful war work from home, as this leaflet explained. In total war everybody did their bit.

Pathé, Movietone and Gaumont were the principal privately owned producers of newsreels.

Charles Pathé and his brothers founded the Société Pathé Frères in Paris in 1896, adopting the national emblem of France, the cockerel, as the trademark for their company. French Pathé began its newsreel in 1908 and opened a newsreel office in Wardour Street, London in 1910.

During the First World War, Pathé’s Animated Gazettes began to give traditional newspapers a run for their money, and often beat their press competitors to a scoop. By 1930, British Pathé was covering news, entertainment, sport, culture and women’s issues through programmes including the Pathétone Weekly, the Pathé Pictorial, the Gazette and Eve’s Film Review. Associated British Picture Corporation (ABPC) acquired British Pathé in 1937 and in 1940, Warner Bros in the United States bought a large holding in the firm.

Poster explaining how householders could seek shelter and compensation if their homes were damaged in a raid.

Another classic Abram Games poster graphically emphasising that the more crops grown at home the fewer vital spaces required in the holds of ships to transport foodstuffs to Britain.

‘This is a War of Machines’ national savings leaflet explaining that in modern war it was the duty of citizens to provide their armed forces with the best equipment – and that this cost money.

With so many able-bodied men away on active service it was vital that the factories and foundries were staffed by capable workers. This leaflet explained how those exempt from fighting could participate in industrial production.

British Movietone News, a subsidiary of US Corporation Fox Movietone News, released newsreels in Britain from 1929 to 1979. Leslie Mitchell, the first commentator for the new BBC Television Service when it began transmissions on 2 November 1936, was also a commentator for British Movietone News. In September 1939, Mitchell and other Movietone editorial staff were evacuated to Denham, although they returned to Soho Square soon after. Mitchell worked for Movietone throughout the war, and was also commentator on War Pictorial News, which began production in 1940.

The third major player in the late 1930s and throughout the war years was Gaumont-British News. Originally dealing solely in photographic apparatus, the company began producing short films in 1897 to promote its own cameras and film projectors. In 1914, however, Léon Gaumont’s Cité Elgé studios in La Villette, France were the largest in the world. Gaumont dominated the motion-picture industry in Europe until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Gaumont also constructed London’s Lime Grove Studios, used by the BBC prior to its move to the TV Centre at White City in the 1960s.

Together with newspapers and the newsreels the public also referred to a series of regular magazines to keep up to date with the progress of the war and developments at home, such as items about new fashion trends or Hollywood celebrities – anything in fact to take their minds off the drudgery of rationing and the bleakness of the blackout.

Picture Post, essentially Britain’s equivalent of the American illustrated magazine Life, was founded in 1938. From the start Picture Post adopted a liberal and distinctly anti-fascist stance. From 1940 the legendary journalist and picture editor Tom Hopkinson took over as editor, previously he had worked on Weekly Illustrated and Lilliput magazines. Most famous for the quality of its photo-journalism, under Hopkinson’s auspices, the very human photographs of luminaries, such as native Londoner Bert Hardy, were given priority. In only its second month the magazine was selling 1,700,000 copies per week. This is one reason why so many of these fantastic publications survive to this day and are inexpensive and accessible to collectors.

Picture Post pulled no punches. As early as 1938 its picture story, ‘Back to the Middle Ages’, exposed the reality of life in Nazi Germany, and revealed the dark character of the Reich’s leaders Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Göring. It is amazing that Picture Post’s publisher and owner, the Conservative party member Sir Edward G. Hulton, tolerated Hopkinson’s left-wing views, which always took precedence over stories from the right wing of British politics in the magazine.

In January 1941 Picture Post published its ‘Plan for Britain’ which proposed minimum wages throughout industry, full employment, child allowances, a national health service, the planned use of land and a complete overhaul of education. ‘Plan for Britain’ was an influential forerunner to the 1942 report Social Insurance and Allied Services (known as the Beveridge Report) which served as the basis for the post-Second World War welfare state.

It is comforting to learn that while the war was very far from over, Britain’s administrators were confidently looking to a better and more prosperous life for their citizens post-war.

Published in December 1942, the Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Social Insurance and Allied Services, to give the Beveridge Report its proper name, set out to tackle what its author considered the five ‘giant evils’ of modern society: squalor, ignorance, want, idleness and disease. Beveridge proposed widespread reform to the system of social welfare to address these issues, famously saying: ‘All people of working age should pay a weekly National Insurance contribution. In return, benefits would be paid to people who were sick, unemployed, retired, or widowed.’ The notion of free health care to all citizens and universal child benefit given to parents was revolutionary. The Labour Party’s election victory in 1945 saw many of Beveridge’s reforms implemented and on 5 July 1948, the National Insurance Act, National Assistance Act and National Health Service Act came into force, and Britain’s welfare state was born.

Britain’s wartime government didn’t just consider the social welfare of its citizens it also thought long and hard about where and how its population would live in a presumably victorious country once the fighting had ended. With large areas of the urban environment devastated by enemy bombing, such considerations were of vital significance if those fighting men returning from active service were going to live in a land fit for heroes.

As early as January 1940 the government convened a Royal Commission on the Distribution of the Industrial Population which was required to inquire into the ‘causes which have influenced the present geographical distribution of the industrial population of Great Britain and the probable direction of any change in that distribution in the future’. It was to consider what social, economic and even strategic disadvantages arose from the concentration of industries or of the industrial population in large towns or in particular areas of the country and then to report what measures, if any, should be taken in the national interest to remedy this and planning deficiencies.

In 1927 Procter & Gamble purchased Oxydol, a laundry detergent created in 1914 by Thomas Hedley Co. of Newcastle upon Tyne. Before WW2, Oxydol, now an international brand, was the sponsor of America’s Ma Perkins radio show - the first soap opera!

Front page of a four page flyer for the Secrets of the Flying Bomb exhibition held in Leicester Square in 1945. Showing how the ‘various automatic devices controlled the robots in flight’ this exhibition helped Londoners come to terms with both the pulse-jet powered V-1 Buzz Bomb, or Doodlebug, the first proper cruise missile, and the far more terrifying supersonic ballistic V-2 rocket.

Germany fired 9,521 V-I bombs on southern England and although around half were destroyed by anti-aircraft fire or RAF fighters an estimated 2,754 people were killed by them, with 6,523 wounded. Over 5,000 V-2s were fired on Britain but only 1,100 reached their target. Nevertheless they killed 5,475 people and wounded another 16,309.

Civil Defence First Aid and Home Nursing Supplement. The fear of a sinister death delivered from the air which so troubled people in the 1930s returned to haunt them in the 1950s during the nuclear standoff between East and West. ‘It is estimated that first aid might have to deal with 20,000 casualties following an air burst of a nominal atomic bomb … ’began the introduction to this Commonwealth booklet.

The Commission published findings which among many other recommendations decided that there should be continued and further redevelopment of congested urban areas, where necessary the decentralisation or dispersal both of industries and industrial populations from such areas and appropriate diversification of industry in each division or region throughout the country. It argued that:

The continued drift of the industrial population to London and the Home Counties constitutes a social, economic and strategical problem which demands immediate attention. The Central Authority should examine forthwith and formulate the policy or plan to be adopted in relation to decentralization or dispersal from congested urban areas in connexion with such issues as garden cities or garden suburbs, satellite towns, trading estates, further development of existing small towns or regional centres, etc. In all cases provision being made for the requirements of industry and the social and amenity needs of the communities, the avoidance of unnecessary competition, and the giving of due weight to strategical considerations. Without excluding private enterprise municipalities should be encouraged to undertake such development, if found desirable on a regional rather than on a municipal basis, and they should be assisted by Government funds, especially in the early years. All existing and future Planning Schemes should be subject to the Central Authority’s inspection with a view to possible modification.

The Government should appoint a body of experts to examine the questions of compensation betterment and development generally.

On 15 August 1942 Lord Justice Scott’s Committee on Land Utilisation in Rural Areas was published. It considered: ‘The conditions which should govern building and other constructional development in country areas consistently with the maintenance of agriculture, and in particular the factors affecting the location of industry, having regard to economic operation, part time and seasonal employment, the wellbeing of rural communities and the preservation of rural amenities.’ The Committee concluded that if no centralised authority directed planning, industry and its necessary supporting housing would continue to be established on the peripheries of Britain’s existing great population centres leading in particular to the still greater growth of London and Birmingham. It argued that the current drift of population to the towns could be countered by improving housing and general living conditions, and so equalising economic, social and educational opportunities in town and country. The improvement of rural housing and amenities would be a key factor in balancing things out and ensuring that those living in rural communities enjoyed actually quite basic facilities such as electricity and piped water, which those in urban areas had begun to take for granted.

The following month Mr Justice Uthwatt’s Expert Committee on Compensation and Betterment published its final report which analysed the subject of the payment of compensation and recovery of betterment in respect of public control of the use of land, and the payment of compensation on the public acquisition of land, advising what steps should be taken to prevent the work of reconstruction after the war from being prejudiced. Uthwatt’s Report viewed post-war reconstruction as the rebuilding of war-devastated areas combined with the modernisation of such areas so that they met the requirements of modern living.

‘Targeting Tomorrow, No. 5, The Nation’s Health’. The establishment of the National Health Service immediately after the Second World War was seen by many as a fitting reward for the sacrifices working class people had once again made for their country.

Rebuilding Britain. The Greater London Plan which had been formulated in 1944 and the New Towns Act which came on to the statute books in 1946 conspired to change the face of post-war Britain.

‘Homes Fit For Heroes!’ That was the promise to returning soldiers after the Great War. The landslide victory for Clement Attlee’s Labour government in July 1945 brought similar promises but this time new houses were constructed with vigour.

The Council of Industrial Design’s New Home brochure, 1946.

Best known for the post-war re-planning of London – he published the County of London Plan in 1943 and the Greater London Plan in 1944, Sir Patrick Abercrombie originally trained as an architect, becoming Professor of Town Planning at University College London. His legacy also remains in the modern rebuilding of cities such as Plymouth, Hull, Bournemouth and Bath as well as award-winning architecture in Dublin.

In 1945, the former Director General of the BBC, Lord Reith, was appointed chair of the government’s New Towns Committee, established to consider how best to repair and rebuild urban communities after the ravages of the Second World War. Recommending the construction of new towns planned by development corporations supported by central government, the New Towns Act of 1946 was the result of the Committee’s deliberations. Basildon, Crawley, Stevenage, Cwmbran, East Kilbride among other new conurbations in Great Britain soon evolved from drawing board schematics into the reality of bricks and mortar.

While committees and town planners published report after report containing their visions of a better Britain and improved communities for the body public which had toiled so long to preserve its national identity, some people wanted simply to pick up where they had left off in 1939 and return to familiar homes and streets. To some, of course, their once familiar streets looked very different. Rows of terraced houses now revealed the occasional gap, like a missing tooth, where a dwelling had been levelled by bomb blast. Many were forced to seek new homes.

Strategy for Survival. First Steps in Nuclear Disarmament. A Penguin Special by Wayland Young (1959). ‘This is a book for clear-minded people tired of hot air who seek a practical guide to the desperately urgent problem of nuclear warfare.’ The son of the politician Edward Hilton Young, 1st Baron Kennet, and the sculptor Kathleen Scott, née Bruce, widow of Captain Scott of Antarctic fame, Young served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War, then began a career as a journalist, writer and Labour politician.

Fortunately the government had an expedient answer to the sudden shortage of homes – the supposedly temporary prefabs, kit houses that could be assembled in days rather than months. There were Airey Houses, designed by Sir Edwin Airey, to the Ministry of Works Emergency Factory Made (EFM) housing programme’s plan, which featured frames of prefabricated concrete columns reinforced with tubing recycled from military vehicles, with walls consisting of a series of ship-lap-style concrete panels. Along with Airey Houses there were also numerous of the more familiar single-storey rectangular prefabs which consisted of steel or aluminium panels fixed to a timber or steel frame; simple dwellings of the kind originally envisaged by Winston Churchill and committed to legislation with the passing of the Housing (Temporary Accomodation) Act 1944.

Between the years 1945 and 1951, when the programme officially ended, 156,623 prefab houses were constructed. Envisaged to last just ten years, the author quotes an article published in the Daily Mail in 2011, sixty years after they were constructed, about Britain’s last surviving prefab estate at Catford, South London: ‘Plonked on top of pre-plumbed concrete slabs, these homes could be built in a day by teams of German and Italian prisoners-of-war who were in no hurry to return home, come the peace.’

Some people returned to homes that although they were structurally sound and had not been demolished by either the Luftwaffe or the local authority’s wrecking ball, were in need of urgent maintenance and repair. Fortunately, early in the war, the War Damage Commission had directed the passing of the War Damage Act 1941. This legislation provided for the payment of compensation for war damage to land and buildings throughout the country, with repairs being carried out by local authorities or private contractors.

In June 1946, this letter from King George VI celebrating victory was sent to every school child in Britain.