CHAPTER 6

The new armies taking to the field at the turn of the twentieth century were very different to those who had gone to war in previous generations. For centuries soldiers had rammed iron balls down the barrels of muskets and cannons, sending them flying after igniting a charge of black powder. Indeed, so inaccurate and low powered were the firearms of the day that rival armies had to line up front of each other with not much distance between and discharge their weapons from massed ranks in the hope that a percentage of the shots expelled would inflict casualties upon their enemies. Smoke from gunpowder quickly enveloped the battlefield meaning the only way for armies to distinguish friend from foe was if they each wore uniforms of bright and contrasting colours.

Rifled barrels, percussion caps and smokeless cordite had revolutionised the battlefield. Guns were more powerful, could shoot accurately over greater distances and their discharge didn’t fog the battlefield. Gone forever were high-visibility uniforms and the need for soldiers to operate in massed ranks. Camouflage and concealment was the name of the game and an understanding of the science of ballistics and the mathematics of hitting targets at long range instead of nearby over open sights became essential to military success.

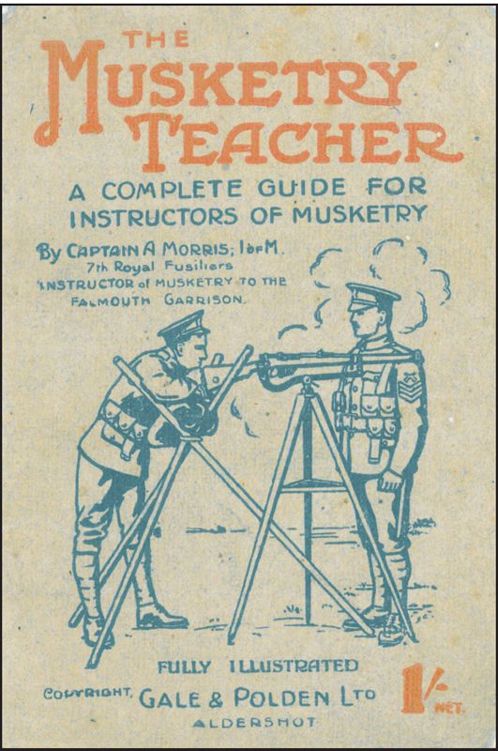

The Musketry Teacher (Gale & Polden, 1916). ‘A complete guide for instructors of musketry by Captain A Morris, 7th Royal Fusiliers Instructor of Musketry to the Falmouth Garrison’.

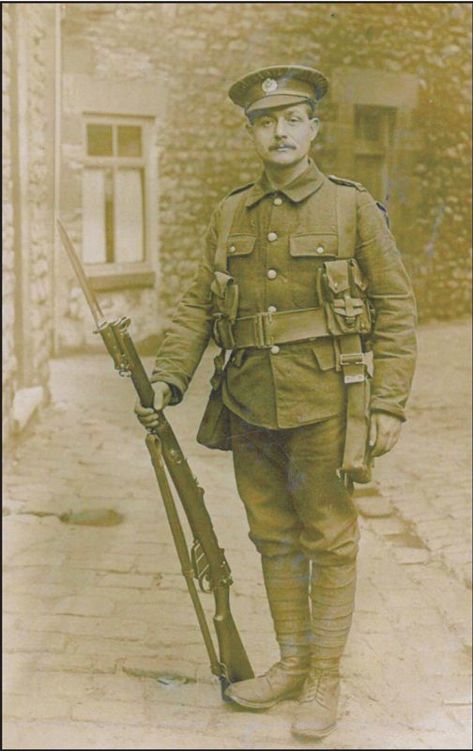

Resplendent in woollen khaki serge Service Dress, complete with 1908 webbing and carrying the accurate and reliable .303 Short Magazine Lee–Enfield (SMLE), the soldiers of the British regular army who marched to the front in 1914, the ‘Old Contemptibles’, were a well-trained and well-equipped modern fighting force. There just weren’t enough of them. Postcards like this are some of the most accessible collectables of the Great War.

Gale & Polden’s Semaphore Simplified. Or how to learn it in a few hours. Priced 6d and dating from around 1900 but used throughout the First World War, this set of illustrated cards vividly illustrates the massive developments in communications technology in the twentieth century. By late 1969 the American Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET), the progenitor of the Internet, was ready to send messages via a nuclear-blast resilient network to US ICBM silos.

The battlefield had become far more complicated. It now also occupied three dimensions as aircraft demonstrated their warlike capabilities. At sea, wood and sail had been replaced by steel and steam propulsion. Naval ships also benefitted from the improvements in ordnance enjoyed by land forces. In the Royal Navy Armstrong’s rifled breech loaders were capable of hitting targets out of sight over the horizon and sailors learned about rangekeeping, the science of accurately judging a target’s range and bearing. If a target was visible then optical rangefinders were employed, if not, mechanical computers performed position predictions using a linear extrapolation of the target’s course and speed.

While conflicts like the Boer War had already demonstrated the changing face of warfare and, in the case of the British Army, heralded the introduction of khaki uniforms and bolt-action, magazine-feed rifles, the novice conscripts who joined the armies, air forces and navies squaring up against each other from August 1914 were in desperate need of tuition in the technology of war. This requirement and the exponential rise in literacy among the working class in the late Victorian period saw a huge increase in the production and distribution of military manuals which could both be used in the field or during training before a soldier saw combat.

The principles and details of training were laid down in the Field Service Regulations and in army publications like Infantry Training 1914 as recruits began basic training and improved their physical fitness. Basic training, as it was known, taught individual and encouraged unit discipline – team work being critical to the success of regiments, battalions and smaller units such as companies, platoons and sections. Recruits were taught how to follow commands, how to march and how to safely handle weapons. Because these former civilians were going to live ‘rough’ in the open, they were also taught basic field craft.

Britain did, of course, possess training bases at home, where a recruit could learn the basics of drill and the specific skills required by the arm of service (i.e., infantry, machine-gunner, artilleryman, engineer) he had joined before going abroad to be trained further and then released for active service, but, right from the start these were found to be inadequate, such was the size the Kitchener’s new army had grown to. Consequently, many additional training camps were developed and traditional infantry training facilities at Aldershot and Catterick, for example, were supplemented by additional instructional barracks built at Cannock Chase in Staffordshire (known as Brocton Camp and Rugeley Camp), constructed with the permission of Lord Lichfield, on whose estate they were being built, at Clipstone in Nottinghamshire and in East Anglia and on the North Wales coast. The Infantry Battle School (INFBS) at Brecon in Wales was further extended in early 1939 and known as ‘Dering Lines’ after Sir Edward Dering who, in 1689, raised the 24th Regiment of Foot – the famous South Wales Borders of Zulu War fame, more recently, the Royal Regiment of Wales.

When new recruits arrived overseas their training continued and the brutal realities of what men were about to face began to sink in as they learned how to deal with the threat of gas, the wounds caused by rifle bullets, shrapnel and the nearby detonation of high explosives. Major Generals Ivor Maxse and Arthur Solly-Flood were closely involved in ensuring that soldiers learned all about the techniques of the new warfare they were about to encounter. The infamous ‘Bull Ring’ at Étaples, seen of the well-known mutiny by British troops subject to the notorious discipline at this camp in September 1917, is probably the most well-known of the transit camps in France and Flanders during the Great War.

Resting at Étaples on his way to the front, the poet Wilfred Owen recorded the following words about the establishment:

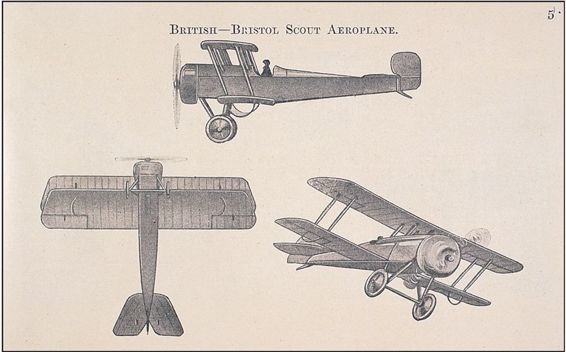

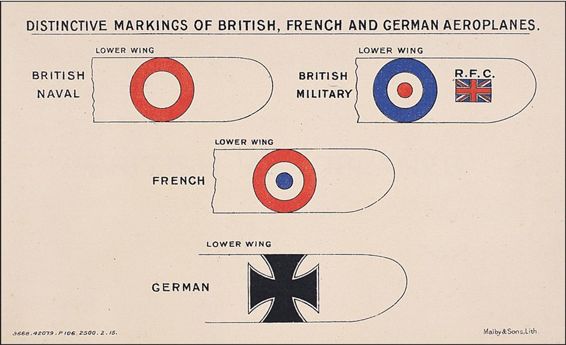

Because they only fly because they all follow the predictable and established aeronautical principles, aircraft all look pretty similar. This was particularly true of First World War biplanes. Knowing exactly which machine was an opponent was critical and led to the introduction of recognition manuals like this one.

I thought of the very strange look on all the faces in that camp; an incomprehensible look, which a man will never see in England; nor can it be seen in any battle but only in Étaples. It was not despair, or terror, it was more terrible than terror, for it was a blindfold look and without expression, like a dead rabbit’s.

At least British recruits enjoyed up to a year’s training before they faced the enemy. German soldiers, on the other hand, often found themselves flung into the teeth of battle after only one month of the most rudimentary training. British soldiers also benefitted from a network of schools teaching specialist skills, learning how to command a platoon or company; how to be a sniper; how to use the use the primitive radio technology available; or operate machine guns like the Vickers or Lewis gun.

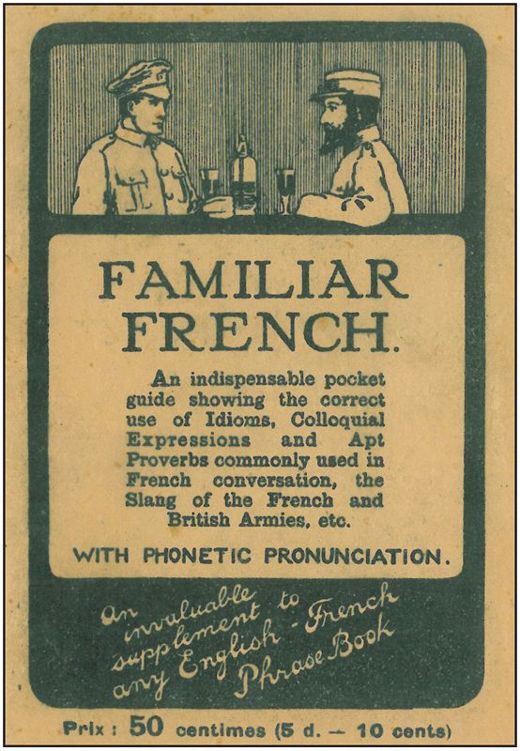

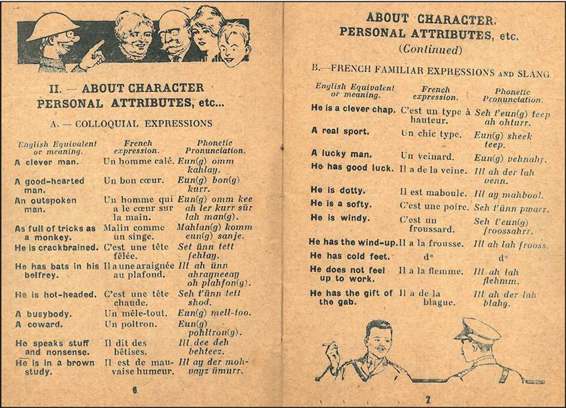

Alongside instruction about the weapons they might employ while on active service in France, British soldiers – most of whom had never been much farther than a visit to their nearest county town or seaside resort, and had never been abroad – were given some rudimentary tuition in the language they were to encounter. French publishers wasted no time in capitalising on a captive market keen, when not in the front line, to converse with lonely mademoiselles or at least order a bottle of affordable vin rouge from the first intact estaminet they could find. Familiar French – with phonetic pronunciation no less, was one of the many such indispensable guides available to Tommies keen to do their best when faced with the need to communicate with their Gallic allies.

‘An invaluable supplement to any English-French phrase book’, Familiar French promised to provide the idioms, colloquialisms, familiar expressions, slang expressions in common use by the French. It cost only 50 centimes. For another 1 franc 50 centimes, Boulogne-Sur-Mer-based publisher Jean Herrebrecht also offered sets of ten cards, ‘artistically coloured’, in the series Sketches of Tommy’s Life in France.

Let them know at home about your life in France by sending from time to time Mackain’s post cards. This series in the artist’s well known humorous style consists of four sets as follows:

1st Set In Training

2nd Set At the Base

3rd Set Up the Line

4th Set Out on Rest

There will come a time when you may be glad to have something of this sort to remind you of the bright or funny side of the war. Take the first opportunity to secure the entire lot. These cards can be obtained at any shop which stocks ‘Familiar French’ – or directly from the publisher of this booklet – small notes accepted in payment.

The reader might be interested to learn that Fergus Mackain, the artist of the postcards in question which did, indeed, prove terribly popular, was a Canadian who worked his way to England at the start of the war, where he joined the British Army and served with the 23rd Royal Fusiliers. Wounded on the Somme at the Battle of Delville Wood in 1916, Mackain survived the war but died in North Carolina in 1924 aged only 38.

British troops who found themselves in front-line trenches in Flanders didn’t only have to get to grips with incessant shelling they also needed to learn the local lingo, especially if they wanted to enjoy any free time at the rear. ‘An indispensable pocket guide showing the correct use of Idioms, Colloquial Expressions and Apt Proverbs …’, Familiar French could be their salvation.

Soldiers could partake of more serious instruction by reading any of the numerous instructional guides published by Aldershot’s Gale & Polden. Fully illustrated, The Musketry Teacher, A Complete Guide for Instructors of Musketry by Captain Morris of the 7th Royal Fusiliers, Instructor of Musketry to the Falmouth Garrison, could be purchased for 1s.

On the subject of ammunition supply Morris had this to say:

The ammunition carried in linen bandoliers in chargers is an idea borrowed from the Japanese, who used it with great success in Manchuria. It has the advantage of being easily portable and easily distributed. There are various means of ensuring an adequate supply of ammunition in the firing line.

Prior to an engagement issue additional rounds to each man. The issue should be as late as possible in order to avoid fatiguing the men sooner than necessary. The Germans issue as much as a man can carry without undue fatigue.

Husband ammunition during fight. Good fire control is necessary. Do not open fire at long range except when imperative or favourable target presents itself. Lack of fire discipline in the personnel of a company is responsible for a great waste of ammunition, such as opening fire without good cause. Misapplication of fire to a target i.e., the use of rapid fire where slow fire was only justified.

In the defence it should be possible to collect the ammunition of all casualties.

Reinforcements should bring up fresh supply of ammunition to firing line.

Ammunition should be sent up whenever opportunity offers during a pause in the fight. The Japanese used this method with appreciable success by sending forward all unemployed men under an officer and non-commissioned officer. The firing line was very often reinforced with the chief idea of replenishing the ammunition supply.

One non-commissioned officer and a few men should be detailed from each company as ammunition carriers. They should supply the reinforcements with ammunition.

Reinforcements may be used to replace the firing line in future advances. This method is not advisable, as it may lead to misapprehension which may entail very serious consequences.

Men should not be sent back from the firing line for ammunition, as it produces a bad moral effect. Men who take ammunition to the firing line should not withdraw until a suitable opportunity occurs.

For the purpose of arriving approximately at the number of rounds to be carried in ammunition columns, the number of rifles in units is calculated at 500 for cavalry regiments and mounted infantry battalions, and at 1,000 for infantry battalions; other units are not considered, The capacity, in rounds, of vehicles and animals allotted for small ammunition is as follows:

Each S.A.A. cart, 16,000 rounds.*

Each Limbered G.S. wagon, 16,000 rounds.**

Each G.S. wagon 40,000 rounds.

Each Pack animal, 2,000 rounds.

Each Lorry (a ton), 80,000 rounds.***

* Small Arms Ammunition (SAA) train cart.

** General Service Wagon.

*** GMC model 15 truck.

With over 150 pages packed with details which included ‘Common Faults in Aiming’, ‘Daily Cleaning of the Rifle’ and ‘Judging Distance’, this book was published in 1916, just in time for the Battle of the Somme when, as we now know only too well, very few British soldiers ever got the opportunity to raise their muskets offensively before they were scythed down by German machine guns.

There was a lighter side to some of the material produced for the edification of British troops in the field and possibly the most famous and successfully produced publication soldiers read with eagerness was the legendary Wipers Times.

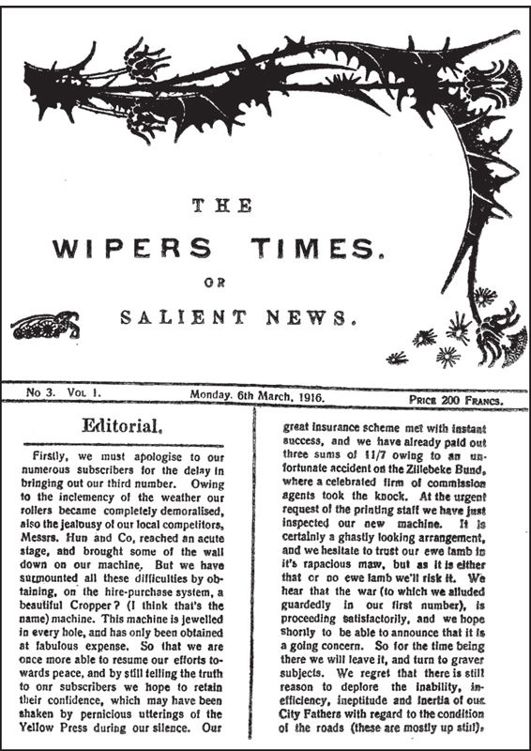

While stationed in Ypres, the heavily shelled Belgian city which blocked the progress of Germany’s Schlieffen Plan, their aim to sweep through the rest of Belgium and into France from the north, men of the 12th Battalion, the Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment), found themselves in the ruins of an old print works. Three of them, Captain Fred Roberts, Lieutenant Jack Pearson and Sergeant Harris, a Fleet Street printer in civilian life, who recognised a pedal-operated printing press for what it was, realised they had the wherewithal to produce a trench newspaper. With Captain Roberts as editor and Pearson as the sub-editor, the Wipers Times was born. The name was chosen because the average Tommy had difficulty with the correct pronunciation of Ypres.

A cross between a parish magazine and Punch, the popular British satirical magazine, the first edition of 100 copies of the Wipers Times was printed on Saturday, 12 February 1916. It went down a storm with the men, editions of the necessarily small print run (paper was in short supply) were read and then passed on from soldier to soldier meaning it reached a readership far in excess of the numbers produced.

The Wipers Times ran from February 1916 until just after the war had ended. It went through several incarnations as the Sherwood Foresters moved from location to location. In fact there were only four editions of the Wipers Times because in April 1916 the battalion moved to Neuve Eglise and the New Church Times ensued. A move to the Somme saw the short-lived Kemmel Times quickly followed by the Somme Times and then eleven editions of the B.E.F. Times. Two editions were printed as the war came to an end in 1918, and, fittingly, these went by the name of the Better Times.

It is easy to see why the Wipers Times and its successors proved so popular with the men in the trenches and so irksome for those in authority. Rereading a facsimile edition while I was preparing this narrative, I was struck by both how funny it was and so anarchic and contemporary in its style. I found it as subversively enjoyable as I did when I watched Monty Python in the early 1970s. It certainly hasn’t dated and is a credit to the wry observations and witticisms of its authors.

There’s an enormous amount of pure gold sprinkled midst the pages of Roberts’ trench newspapers but I’d like to take this opportunity to present a personal selection which, I hope, reveal why they’ve so admirably stood the test of time.

Rightly the stuff of legend. Amid all the official communications and the dos and don’ts soldiers were subjected to while they were trapped in the few square kilometres of mud they inhabited for nearly four years during the First World War, the Wipers Times told it like it was and was a breath of fresh air. Its sardonic, ‘Pythonesque’ humour is as funny now as it was 100 years ago. Editor Captain, later Lieutenant Colonel, Roberts and his sub-editor, Lieutenant Pearson, provided a real tonic for the troops.

From the third edition of the Wipers Times (or Salient News after the ‘Ypres Salient’ within which the printing press was discovered in 1916) published on Monday, 6 March 1916:

Editorial

Firstly, we must apologise to our numerous subscribers for the delay in bringing out our third number. Owing to the inclemency of the weather our rollers became completely demoralised, also the jealousy of our local competitors, Messrs Hun and Co, reached an acute stage, and brought some of the wall down on our machine. But we have surmounted all these difficulties by obtaining, on the hire-purchase system, a beautiful Cropper? (I think that’s the name) machine. This machine is jewelled in every hole, and has only been obtained at fabulous expense. So that we are once more able to resume our efforts towards peace, and by still telling the truth to our subscribers we hope to retain their confidence, which may have been shaken by pernicious utterings of the Yellow Press during our silence. Our great insurance scheme met with instant success, and we have already paid out three sums of 11/7 owing to an unfortunate accident on the Zillebeke Bund, where a celebrated firm of commission agents took the knock. At the urgent request of the printing staff we have just inspected our new machine. It is certainly a ghastly looking arrangement, and we hesitate to trust our ewe lamb in its rapacious maw, but as it is either that or no ewe lamb we’ll risk it. We hear that the war (to which we alluded guardedly in our first number), is proceeding satisfactorily, and we hope shortly to be able to announce that it is a going concern. So for the time being there we will leave it, and turn to graver subjects. We regret that there is still reason to deplore the inability, inefficiency, ineptitude and inertia of our City Fathers with regard to the condition of the roads (these are mostly up still), and the lighting of the town. We should like to see these matters taken in hand at once. There are many more justifiable reasons for dissatisfaction on the part of our fellow townsmen, notably the new liquor laws. We hear that the new night club, which has recently been opened near the Hotel des Ramparts prepares a beautiful ‘cup’ for its patrons. This is a step in the right direction, and long may it flourish. All the stars can be seen there nightly, and consequently all visitors will have reason for satisfaction. This being our grand summer number, we have doubled the price, as is usual on these occasions. Before closing we must thank our numerous subscribers for the kindness we have received, both congratulatory and financial. A Happy Xmas to you all!

THE EDITOR

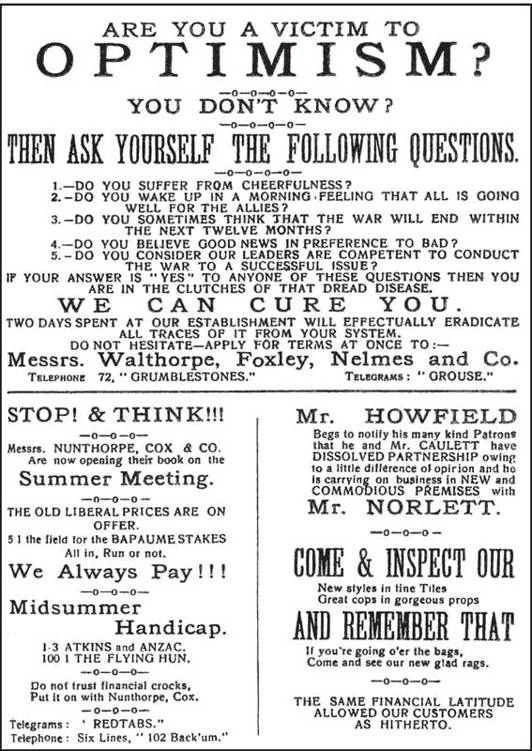

There’s so much more to choose from but perhaps just a couple more short excerpts. First, what about a half-page advertisement which appeared in the Somme Times at the height of that bloody offensive:

Are You a Victim to OPTIMISM?

![]()

You Don’t Know?

![]()

THEN ASK YOURSELF THE FOLLOWING QUESTIONS.

![]()

Do you suffer from cheerfulness?

Do you wake up in the morning feeling that all is going well for the allies?

Do you sometimes think that the war will end within the next twelve months?

Do you believe good news in preference to bad?

Do you consider our leaders are competent to conduct the war to a successful issue?

If the answer is ‘yes’ to anyone of these questions then you are in the clutches of that dread disease.

WE CAN CURE YOU

Given the high esteem in which war poets like Owen, Sassoon, Brooke and others are rightly held today, the fact that during the conflict Roberts and his colleagues famously protested against the amount of poetry they received is another fine example of the irreverent and subversive humour exhibited by the Wipers Times.. OK, so it’s a bit ‘public school’ and I’m sure it went over the heads of many of the coarser enlisted men who read it, but it is very funny nonetheless:

We regret to announce that an insidious disease is affecting the Division, and the result is a hurricane of poetry. Subalterns have been seen with a notebook in one hand, and bombs in the other absently walking near the wire in deep communication with the muse … The editor would be obliged if a few of the poets would break into prose as a paper cannot live by ‘poems’ alone.

And finally:

CAN YOU SKETCH?

Some of you may be able to draw corks.

Very few of you can draw any more money.

Probably some of you can draw sketches.

Here is a letter I have just received from a pupil at the front:

‘The other day by mischance I was left out in No-Man’s Land. I rapidly drew a picture with a piece of chalk of a tank going into action, and while the Huns were firing at this I succeeded in returning to the trenches unobserved’

Could you have done this?

Send a copy of the following on a cheque:– Francs 500 –

And by return I will send you a helpful criticism and my fourteen prospectuses.

Please sign your name in the bottom right-hand corner to prevent mistakes.

The editor, Fred Roberts, was later promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and received the Military Cross for his war service. He died in Toronto, Canada in September 1964.

Fighting on the Western Front during the First World War was characterised by long periods of boredom abruptly punctuated by moments of sheer terror when men were pushed to the edge and subjected to unimaginable horrors which would stay with them for ever, if they survived the fighting. Relief from the drudgery and monotonous routine of army life was found in entertainments such as the Wipers Times, love letters from home, playing cards, or in fact, reading just about anything they could get their hands on.

Perhaps because it was targeted at working class men, the heavily illustrated magazine War Illustrated had become one of the most popular reads among men in the trenches. In December 1915, War Illustrated published an article about how soldiers looked forward to and enjoyed reading books sent from Britain. The publication urged readers on the home front to send soldiers abroad as many books as they could.

Fortunately by 1914 the General Post Office (GPO) was Britain’s largest economic enterprise; indeed, with over 250,000 people employed it was the largest single employer of labour in the world. It was big enough to cope with the deluge of mail to and from the front. I should point out, however, that by 1918 28,000 GPO staff had enlisted in the armed forces and that by the end of the conflict 73,000 staff had joined up. The Post Office even had its own battalion, the Post Office Rifles (POR), comprised entirely of postal staff. Sadly, like so many of the other ‘pals’ battalions, made up of men who knew each other in ‘civvie street’, the POR fought and died together, the unit suffering badly at Ypres in 1917.

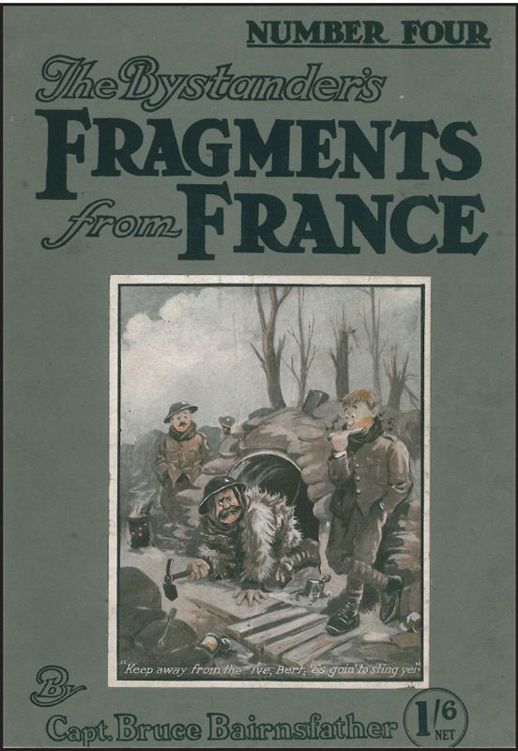

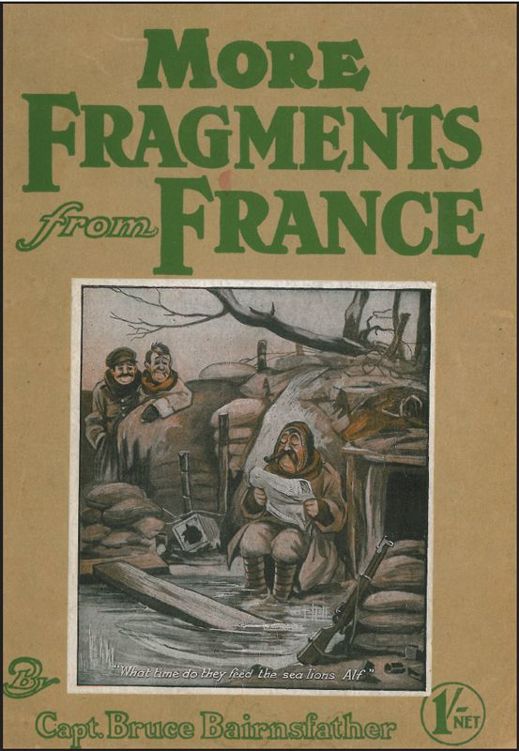

Like Fred Roberts, Bruce Bairnsfather has entered the pantheon of the good and great who brought some normality to the troops of the western front in the First World War. Famous for ‘Old Bill’, the curmudgeonly but worldly-wise British soldier who adorned a thousand postcards, and who appeared in the weekly Bystander Magazine, Bairnsfather’s cartoon creation also appeared in compilations such as Fragments from France and More Fragments from France, as illustrated here. The price of original editions of these poignant reads has increased dramatically given the centenary of the First World War.

All post bound for troops on the Western Front was sorted at the GPO’s London Home Depot which by the end of 1914 covered 5 acres of Regent’s Park. During the war the Home Depot handled 2 billion letters and 114 million parcels. The Army Postal Service (APS) was responsible for distributing mails in the theatre of war and coordinated communications with battalions, right up to the front. During the First World War up to 12 million letters a week were delivered to soldiers in all theatres of war, not just in France and Flanders but in the Dardanelles, the Middle East and Africa.

From 1915, Lord Kitchener yielded to political pressure and allowed newspaper reporters onto the Western Front. At first six war correspondents were appointed to GHQ in France and worked in a pool system for publication in the national press. They wore uniform, but were closely escorted by suspicious regular escort officers and were rarely able to report accurately on the full horror of what they saw. This was mostly, of course, because they operated some distance behind the front line! However, one journalist in particular, Philip Gibbs of the Daily Chronicle, achieved the respect of the politicians at home, Generals at GHQ and even the men in the trenches, when and if old copies of newspapers reached them.

Between February 1918 and June 1919, the United States Army even managed to publish its own newspaper, the Stars and Stripes, actually produced in France for the information, education and entertainment of the growing ranks of dough boys swelling the Allied armies.

When not in action men did, in fact, have plenty to read although it has to be said that they enjoyed lighter reading and even novels, particularly those written by H.G. Wells or Rudyard Kipling, to the latest official army bulletins about operational procedures or how to field strip a Lewis gun.

Immediately prior to the First World War there was already a thriving market for technical handbooks about new flying machines as this book, Aircraft, Airships, Aeroplanes etc, demonstrates.

The coming of peace in 1918 brought respite to the war-weary nations of Europe. The victors, France and England, had nearly bankrupted themselves to persecute such a worldwide conflict. The Austro-Hungarian Empire had been broken up and Germany saddled with almost unimaginable reparations in accordance with the diktats of the Treaty agreed at Versailles in 1919. The United States emerged even stronger, its massive industrial capacity undamaged by war and easily able to switch to a peace-time footing and provide eager consumers with the new, benign products of the production line such as automobiles, electric cookers and vacuum cleaners. There was inevitably a surplus of military items manufactured to feed the greedy warring combatants and aeroplanes, particularly, could be purchased cheaply. The easy availability of now-obsolete but nevertheless strong and powerful aircraft led to a huge increase in barnstorming and stunt flying, particularly above the wide open spaces of North America.

The aeroplane didn’t just promise excitement and entertainment, of course, and though peace time certainly offered the opportunity to harness modern development in aviation to explore uncharted wildernesses, flying machines were also harbingers of bad things to come.

Even by 1918 the apparently flimsy biplanes had proved themselves capable of military versatility, dropping increasingly heavy bomb loads and offering pretty stable platforms from where machine guns could be fired. As early as 1912, Bradley Fiske, an officer in the United States Navy, had taken out a patent for an aerially launched torpedo. In 1914 the Royal Naval Air Service managed the first successful aerial torpedo launch by dropping a Whitehead torpedo from a Short S.64 seaplane. The United States bought its first batch of ten torpedo bombers in 1921, and in 1931, the Japanese Navy developed the Type 91 torpedo, dropping it from a height of 330ft at a speed of 100 knots.

If these developments weren’t frightening enough, the possibility that aircraft might also employ chemical weapons – poison gas, like that used to such awful effect on the Western Front, further vexed the military authorities. Despite the prophecies of the Italian General Douhet and the British author H.G. Wells, both convinced that military airpower was invincible – even the British politician Stanley Baldwin pronounced, ‘The bomber will always get through’ in a speech to the House of Commons in 1932 – military authorities had to develop methods to counter the threat from the air.

Until the timely development of radar in the late 1930s, the only defence came in the shape of the Heath Robinson-esque, and frankly useless, Sound Locators, giant ear-trumpets supposed to be able to detect incoming aircraft before they could be visibly observed, and good old anti-aircraft (AA) guns.

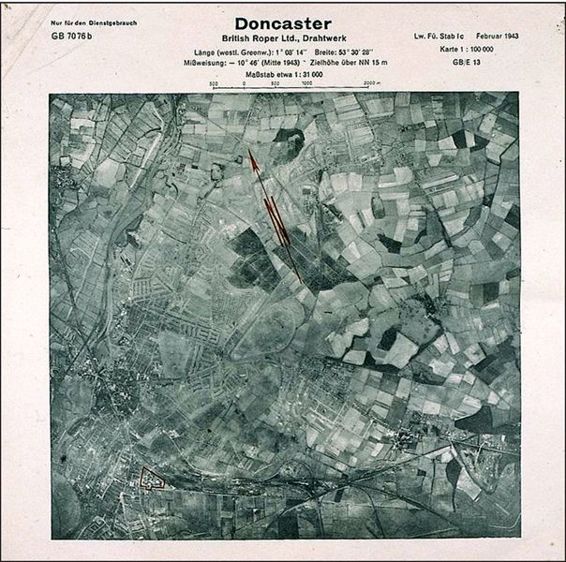

The Luftwaffe flew hundreds of reconnaissance sorties over Britain and went to extraordinary lengths to ensure bombing missions were despatched to priority targets such as this industrial concern in Doncaster. Remarkably, these photographs can still be purchased and remain relatively inexpensive.

In my collection I have a particularly rare 1928 edition of Gunners’ Instruction for Second and First Class Gunners employed in US coastal artillery gun batteries. A series of useful instructions delivered in question and answer format, it makes very interesting reading:

Q. What does the propelling charge consist of?

A. Nitrocellulose powder.

Q. What does the bursting charge of a high explosive shell consist of?

A. About one-and-a-half pounds of high explosive powder.

Q What does the bursting charge of shrapnel consist of?

A. About one-fifth of a pound of shrapnel powder.

Q. What does the shrapnel filling consist of?

A. About 253 half-inch lead balls, and a smoke producing powder filled in the space between the balls.

Q. What happens when a shrapnel projectile bursts?

A. The fuse is blown off and the projectile acts as a shot gun, the lead balls being ejected through the nose at an increased velocity.

Bombing planes fly in close formations, usually with not more than 50 yards between planes. It is seldom that less than 5 or more than 18 bombing planes cross the lines in a single formation, as formations of more than 18 planes are not easily maneuvered.

During the first week of July 1937, less than ten years since this manual was distributed, the German Condor Legion launched a coordinated attack on Spanish Republican forces at the Battle of Brunete. Then, as Messerschmitt Bf-109B fighters flew high above Heinkel He-111 bombers, who were in turn co-ordinating their attack with Heinkel He-51 biplanes a further 500ft below, literally dozens of Luftwaffe aircraft exhibited that it was quite easy to manoeuvre massed formations of far larger size than just ‘18 planes’.

Published in reaction to the demonstrations organised by American General Billy Mitchell which revealed the vulnerability of warships and seacoast defences to air power, this copy of Gunners’ Instruction for an American coastal anti-aircraft battery dates from 1928.

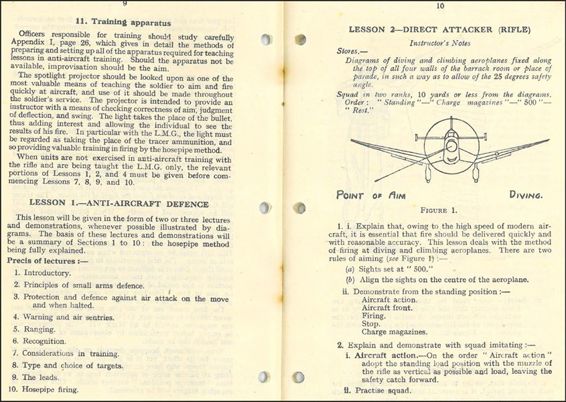

By 1939 it was imperative that those involved with air defence were able visually to distinguish between the warplanes of rival belligerents. Those involved in antiaircraft and those in civil defence whose job it was to issue the warning of an incoming raid had to be capable of telling the difference between an assortment of monoplanes which by this period, because they were all designed on the same proven and published principles of aerodynamics, all looked very similar indeed.

To help gunners and observers recognise friend from foe a series of Aircraft Recognition manuals were produced. They were regularly updated as subsequent improved marks of aircraft took to the skies. For example, during the Second World War there were five basic marks of Messerschmitt Bf-109 alone, as well as numerous sub-variants of each major production run. The Spitfire actually progressed through an amazing 24 different marks during the same period when an amazing 20,300 examples of this iconic fighter were manufactured.

In April 1943 Peter Masefield, Technical Editor of the Aeroplane and Editor of the Aeroplane Spotter, wrote:

The Complete Lewis Gunner (Gale & Polden). Although invented by an American in 1911 and used throughout the First World War, as this 1941 publication shows, the Lewis gun was still in service in the Second World War and, in fact, through to the end of the Korean War in 1953.

The Browning Heavy Machine Gun Mechanism Made Easy (1940), another handbook from Gale & Polden’s prolific lists.

There is no short cut to aircraft recognition and the basis of all study of any particular aeroplane must begin with the silhouette. The silhouette presents the true outline and detail of the features which go to make up the machine, free from the distortion or perspective which may give a false impression in a photograph.

Recognising the different silhouettes of the myriad operational aircraft was crucial to air defence during the Second World War. OK, silhouettes weren’t as crucial as radar and radio proximity fuses, but these technological developments were secret, even from those men manning AA batteries. The importance of precise knowledge about differing silhouettes was what was drummed into all those scanning the skies in search of enemy aircraft during wartime.

To aid observers and gunners they were encouraged to study not just the latest recognition manuals but to use other aide-memoires like sets of cards or posters which could be plastered on the walls of billets and examined when soldiers were involved in chores like ‘bulling’ their ammunition boots. Another great help was so-called recognition models, accurately scale miniatures which could be held in the hand and considered from three dimensions. A great improvement over traditional three-view recognition graphics which depicted silhouettes in plan, profile and head-on aspects and often missed distinguishing subtleties of shape and form, recognition models were usually moulded in a black thermosetting polymer such as Bakelite which had taken the world by storm in the 1930s.

Manual of the Sten Gun. You can see that this booklet was aimed primarily at the Home Guard because it includes notes on the Northover Projector, the very rudimentary anti-tank weapon invented by Major Robert Harry Northover, an officer in the Home Guard, who designed each one to be manufactured for under £10.

The Thompson Submachine Gun Made Easy (Gale & Polden, 1942).

The War Office published Small Arms Training Volume 1, Anti-Aircraft in 1942. It was designed to update soldiers with the lessons learned from the various combatants who had encountered Germany’s new blitzkrieg method of warfare – that is the close co-ordination and application of mechanised units moving rapidly forward beneath the umbrella of aircraft who both acted as a shield against aircraft from the opposing side and operated as highly mobile artillery softening up targets ahead which the advancing infantry could quickly envelop. Though the British Army had practised fire and movement techniques in the late 1930s and, in fact, went to war in 1939 as a highly mechanised force, it was not as adept at mobile operations as was the German Army. The PBI (poor bloody infantry) in King George’s army still spent a lot of time marching to their objectives. But, as Small Arms Training Volume 1 pointed out:

So far as troops are concerned, probably the most vulnerable target that presents itself to aircraft is that of a column in line of march. Instructions in this pamphlet are concerned only with low flying attacks or dive bombing attacks within 2,000 feet or 600 yards (ground range). These attacks will be made at high speed and will be quickly over, allowing only three or four seconds during which effective fire is possible … Against undisciplined or demoralized troops air attacks may have a decisive effect. It is of the utmost importance therefore that all ranks should be trained to withstand the noise of air attack and should be imbued with the necessity of hitting back as hard as possible … Troops must not expect that the aircraft when hit will crash immediately. If it remains in the air for only 30 seconds it will fly two or three miles. Personnel therefore must not lose heart if the accuracy of their fire does not bring immediate results.

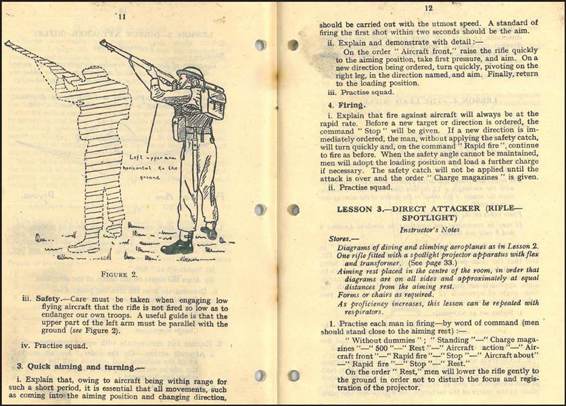

Small Arms Training Volume 1, Pamphlet No. 6 Anti-Aircraft (1942) was a compilation of the lessons learned when British soldiers found themselves subjected to repeated air attack during the battle for France. The image of the BEF infantryman vainly trying to take out dive-bombing Stukas with a single .303 rifle shot has become iconic. ‘Owing to the high speed of modern aircraft, it is essential that the fire should be delivered quickly and with reasonable accuracy.’

Soldiers were taught the importance of ‘leading’, which is aiming ahead of the direction of flight of an enemy aircraft, when shooting at it with rifle or machine gun. Instructors were told to educate their squads accordingly about this essential technique, one that is in fact familiar to anyone shooting game or clays with a shot gun. To help them gauge the degree of lead necessary model aircraft were fitted onto wooden stands with a rectangle of card held on a wire some distance ahead of the aircraft. Trainees then pointed an outstretched arm towards the model, using their extended fingers to judge the degree of offset between target and aiming point. Small Arms Training Volume 1 continues: ‘Explain that each man must measure for himself what part of his left hand when at arm’s length will give 12 degrees from the nose of the aeroplane to the centre of the rectangle. The parts of the hand which gives the measurement at 10 yards will also give 12 degrees at any range.’

Although not involved in developments as leading edge as those taking place in aviation, soldiers also had to contend with familiarising themselves with new techniques of land warfare.

Army Form A 2022 provided soldiers with instructions to follow in the event of gas attack. They were advised that a great deal of personal decontamination could take place immediately, even on the march. Provided with pads manufactured from cotton waste, soldiers were advised to use it to remove ‘free liquid’ which remained on their skin and to rub the ointment with which they were also supplied ‘vigorously into exposed skin for at least 30 seconds with both hands’. They were further told the following:

1. Don’t put your rifle and equipment down on exposed ground.

2. Swab free liquid off web equipment – apply ointment to both sides where contaminated. You can wear it again.

All armies were equipped to deal with gas, as were air forces – the observant reader might have notice the yellow diamond patches on the wings of RAF fighters, such as the Hawker Hurricane. These were patches of a material impregnated with a chemical which would change colour if contaminated by poison gas, giving the pilot a warning sufficient to enable them to push the throttle forward and speed off towards a decontaminated airfield.

Airpower and chemical weaponry aside, armies still had to learn or relearn age-old techniques essential for them to find their way around the battlefield or move from one location to the next. Map reading and the ability for soldiers accurately to judge distance was as important as ever.

In Military Map Reading for the New Army, published in 1940, Captain W. Stanley Lewis said that the ability to ‘read’ a map was an essential element of military education. British maps of 1in to 1 mile, 1/63,360 scale, with relief shown by orange-coloured contours and roads indicating both their surface finish and width; those suitable for speedy traffic being coloured red; poor roads shown in broken yellow and footpaths indicated by dashed lines were superior to German maps, the author argued. He continued, though very detailed, the German 1/50,000 map featured a complicated list of symbols: ‘It is not a very satisfactory map, as so much has been included that its details are difficult to follow. The same criticism applies to the 1/25,000 variety; and the fact that in both types most of the material is printed in black further obscures the matter portrayed.’

Regarding night marching or marching in reduced daylight, Captain Lewis urged reference to the compass:

Marching by night or in conditions of reduced daylight, e.g. in mist or through wooded areas, demands a special technique. To meet such emergencies the compass is graduated around the outer brass ring into 360 degrees, numbered from the lubber line, which is zero, in an anti-clockwise direction. Every 10th degree is marked and numbered thus: 10 degrees by the figure 1, 20 degrees by the figure 2, and so on. The moveable glass cover has a luminous ‘director’ which can be set opposite to any required number of degrees on the brass ring … It is possible to march by stars if they are visible. Select one at the outset, but remember that all stars move through the circle of 360° in 24 hours, i.e. 15° in one hour. Therefore a constant check, say once in every quarter of an hour, is necessary; this involves calculating a fresh bearing.

When it came to judging distance, the other topic covered in Military Map Reading for the New Army, the author said that although technical instruments existed to help with this task, it was often necessary to make estimates by eye. This was no easy task the reader was told, but it was suggested that judging distances based on the lengths of well-known spaces such as the 22yd of a cricket pitch or the 120yd of a football pitch was helpful.

The various distances on a rifle range should be studied and recorded in the memory. It is always useful to remember that 110–130 walking paces cover about 100 yards. The height of the individual, his length of pace and rate of progress determine the exact relation between number of paces and distance travelled. You will always find that there is a tendency to place distant objects farther away than they actually are; only experiment can guide you upon the amount of allowance which must be made.

From the moment war was declared in 1939, the War Office bombarded, no pun intended, soldiers, regulars and new recruits with a never-ending series of A5 size Military Training Pamphlets.

Troop Training for Light Tank Troops was published in November 1939. The fact that it had ‘NOT TO BE TAKEN INTO FRONT LINE TRENCHES’ emblazoned on the front cover is, perhaps, an indication of what a shock blitzkrieg was about to deliver to the men of the BEF, who had more or less taken up the positions in Northern France (they weren’t allowed to enter neutral Belgium) that their fathers had occupied in 1914. Another indication of the innocence and unpreparedness of British troops, even armoured ones, is given by this description of the role, application and capabilities of a light tank troop which only comprised three puny Vickers-Armstrong MkVI tanks, each with hull armour that was only 4mm thick and an offensive armament of two machine guns:

The light tank is armed with two weapons, a heavy machine gun for use against tanks, and a medium one for use against exposed personnel. It also carries a pair of smoke projectors from which smoke candles can be fired to produce a smokescreen to protect the tank from observation of fire. The projectors may, on occasions, be used also to throw a grapnel and line to tow away light obstacles which have been placed by the enemy to obstruct the tank’s advance. The armour, mobility and fire-power of the three tanks of a troop, put in the hands of the troop leader comprise a unit with great powers of reconnaissance and considerable fighting value.

It should be remembered that the nonsense above was written during the period of the ‘phoney war’ when Anglo-French armies dug in along the Belgium border or behind the vaunted Maginot Line, a period when nothing happened save the dropping of propaganda leaflets over opposing lines with each side either arguing their cause or trying to demoralise troops shivering in slit trenches as they endured one of the coldest winters on record.

When the fighting did start in earnest in May 1940 British armour was found to be wanting. The tiny size of Britain’s armoured component was so insignificant that it was almost entirely placed under French command. What tanks survived their encounters with the much better deployed German panzers and the pinpoint accuracy of Stuka dive-bombers were left in France after the BEF escaped from Dunkirk and the other French beaches. No wonder Montgomery later said of this period that the entire British Army was not prepared for a full-scale exercise, let alone a war, in 1939.

The Universal or Bren Carrier was one of the rare success stories, as far as British armoured vehicles deployed early on in the war was concerned. It was another machine built by Vickers-Armstrong at Newcastle upon Tyne. Published in 1940, Military Training Pamphlet No. 13 reveals some interesting details about the little tracked vehicle which found ubiquity in almost every theatre British or Commonwealth troops fought. These are the stores the fully equipped Bren Carrier went into action with: ‘Bren gun, 22 magazines, spare parts bag, spare barrel and tripod. Anti-tank rifle and 8 magazines. Flags – red and blue.’ ‘Flags! In mechanised warfare?’ I hear you ask. Pamphlet No. 13 provides the answer:

If the carriers are on the move, the noise will prevent verbal commands being heard. In such circumstances the section commander will hold the red flag horizontally and dip it two or three times towards the ground. Whilst the carriers are coming to a halt, the duties detailed above will be carried out by the crew.

Albeit slowly, the British Army was learning new methods and adapting to the revolutionary concepts of coordinated armour, mechanised infantry and close air support which the Wehrmacht so ably demonstrated. Britain certainly wasn’t idle after the failure in France. War production was up and new machines were going from the drawing board and into production faster than ever before. In fact, by the end of 1940, Britain’s aircraft output exceeded that of Nazi Germany. If the rules were changing, Britain was determined to master them. Military Training Pamphlet No. 42, Tank Hunting and Destruction caught the new mood at the War office:

Tanks well served and boldly directed have established a superiority on the battlefield which is out of all proportion to their true value; the problem is now to reduce the menace to its true perspective even when elaborate equipment is not available. It has been proved that tanks, for all their hard skin, mobility and armament achieve their more spectacular results from their moral effect on halfhearted or ill-led troops. Consequently, troops which attempt to withstand tanks by adopting a purely passive role will fail in their task, or at the best only half complete it. Tank hunting must be regarded as a sport – big game hunting at its best. A thrilling, albeit dangerous sport, which if skilfully played is about as hazardous as shooting tiger on foot, and in which the same principles of stalk and ambush are followed.

This was all very well of course, but the army wasn’t engaged with large cats in the jungle and it was no longer mainly led by men of aristocratic bearing who had the time and resources for big game safaris. Britain’s new army leaders comprised a hard core of regulars with experience gained in the First World War, although many more still were simply grammar school boys whose vocational path had been interrupted by the war. The reality was, that in 1940 at least, the British Army simply didn’t have weapons of the calibre required to knock out the latest panzers. This can be evinced when one considers the list of weapons available to soldiers who did indeed manage to spring a German tank from its lair. Among a list of armaments available, which included Molotov cocktails, Phosphorous grenades, the Sticky (ST) grenade, the Harvey flame thrower (a 22-gallon capacity tank of flammable liquid mounted on a wheeled trolley!), the Northover (bottle) mortar (designed for Home Guard use to enable them to launch the AW (Allbright and Wilson) bomb, a potentially lethal milk bottle), the only proper weapon available was the Boys Anti-Tank Rifle. Military Training Pamphlet No. 42 continues: ‘The anti-tank rifle penetrates the armour of the light tank, and that of some heavier models when fired at short range. It is effective against the tracks of the heaviest tanks yet encountered.’ The Boys rifle was almost useless, as the pamphlet so casually explained; unless it was fired at short range. And, it may have penetrated the armour of light tanks, British light tanks, but is was ineffective against the latest German tanks. Furthermore, as one Home Guard veteran told me, it had a fearful kick that was enough to dissuade soldiers from ever reaching for it!

There was one rifle the British soldier could depend on: The trusty Lee–Enfield .303 SMLE, the same weapon troops used in the trenches used during the First World War. Although the No. 4 version of this excellent weapon would replace the trusty Mk III rifle which had served the army so well since 1907, it was, to all intents and purposes, the same weapon.

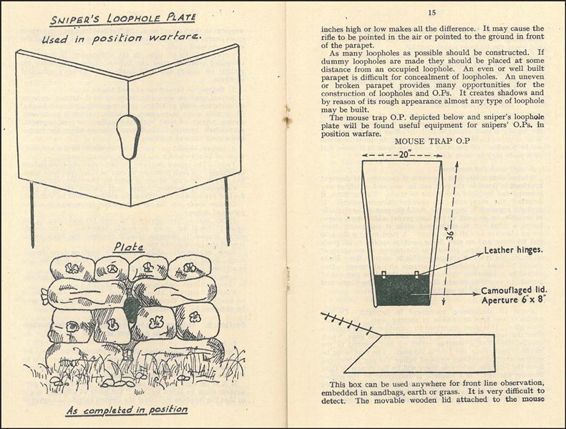

Notes on the Training of Snipers, Military Training Pamphlet No. 44 was published in 1940. The sentence: ‘An even or well built parapet is difficult for concealment of loopholes’ reveals that instead of the rapid movement inherent in blitzkrieg, Britain’s high-command still foresaw the likelihood of trench warfare.

Snipers in the British Army even employed a variant of this classic firearm using the Rifle, .303 Pattern 1914 which was only declared obsolete in 1947.

Military Training Pamphlet No. 44, Notes on the Training of Snipers pulled no punches when it said:

The primary object of a sniper is to kill. Sniping is an old art which came into much prominence during stationery warfare, and its importance was increased by the introduction of the telescopic sight rifle. During the short period of open warfare which occurred during the Great war in 1918 (and also in the recent fighting both in Norway and in France), snipers proved to be indispensable, and by their use of ground, endurance, and expert shooting, were able to put large numbers of enemy weapons out of action by operating on the flanks of the attacking troops. They also succeeded, on several occasions, in putting enemy gun batteries out of action by shooting down the gun crews.

Notes on the Training of Snipers praised the qualities of the British Army service sniper rifle:

The combination of Sniper Rifle (Patt ’14) and telescopic sight is an extremely accurate weapon. The sniper should be capable of taking full advantage of its accuracy. It is capable of producing a one-and-a-half inch group at 100 yards. Although groups at 100 yards as large as four and five inches are acceptable, the soldier should realize that he is not of much value as a sniper unless he can make groups of three inches or less at that range.

Every branch of the armed services had pages of instruction to rely upon. Though a lot would have been very similar to the old salts who served in the Royal Navy at the time of Jutland, sailors in the Royal Navy during the Second World War had lots of new stuff to learn. Naval weapons like the Hedgehog (also known as an Anti-Submarine Projector) was an anti-submarine weapon developed by the Royal Navy to counter the U-boat stranglehold which threatened to starve Britain of food and resources. Based on the British Army’s Blacker Bombard 29mm Spigot Mortar, the Hedgehog fired a number of small spigot mortar bombs from spiked fittings. These exploded on contact and achieved a greater success rate than traditional depth charges.

Collectors of Royal Navy wartime ephemera should also keep an eye out for any leaflets or training manuals associated with ASDIC (an acronym usually wrongly claimed to stand for Anti-submarine Detection Investigation Committee, but actually a conjunction of words to disguise some of the device’s top-secret components such as quartz piezoelectric crystals), the RN’s revolutionary anti-submarine detection system, a prototype of which was ready for testing by mid-1917, only used on HMS Antrim in 1920. ASDIC started production in 1922. Beginning work a bit later than the Admiralty but following a parallel course, the United Stated Navy developed Sonar (SOund Navigation And Ranging), their technique for detecting and attacking submerged enemy submarines. Anything whatsoever to do with either ASDIC or SONAR should be snapped up without delay.

Those in the RAF could refer to The Kings Regulations and Air Council Instructions for the Royal Air Force, a weighty tome of almost 4,000 pages which covered almost every detail imaginable concerning the operation and administration of Britain’s military air arm. In December 1940 a reprint of the 1928 edition, with appendices and index, was published. The Air Ministry preface included the following forthright words: ‘Air and other officers commanding, and commanding officers, will be held responsible that these regulations are observed by officers and airmen under their command, and that any local instructions or orders that may be issued are not inconsistent with the regulations here laid down.’

This copy of Infantry Training Volume 1 Infantry Platoon Weapons dates from 1955 and was the possession of a Lance Corporal in the Buffs. The British soldier’s uniform and equipment had further evolved towards the end of the Second World War and by D-Day many troops wore the new Mk III ‘turtle’ helmet. The outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 was a further spur for change and a new battledress – the 1950 Pattern, made of heavy duty cotton sateen material and based upon the US M1943 uniform which included zips and vents to aid ventilation and was, quite obviously, more comfortable and practical than the old woollen serge battle dress, soon equipped British troops.

There’s quite an assortment of official wartime or interwar RAF material still available on the collectors’ market – though RFC material is naturally much scarcer and consequently more expensive. If you do happen to find anything to do with British military flying which predates 1 April 1918, the date when the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) merged to form the Royal Air Force, you’ve struck gold.

But it’s more likely you will unearth RAF combat reports (RAF Form 1151 or ‘Form F’), which detail the time, date, height and outcome of individual combats or perhaps, even better, individual pilot log books (RAF Form 414), the blue book-cloth covered square record pads charting the operational activities of pilots. At the time of writing examples of vintage log books in good condition were available from around £50, but costing more if they belonged to fighter pilots on operational duties during wartime and even more expensive if they detailed dogfights and, the cherry on the cake, combat kills.

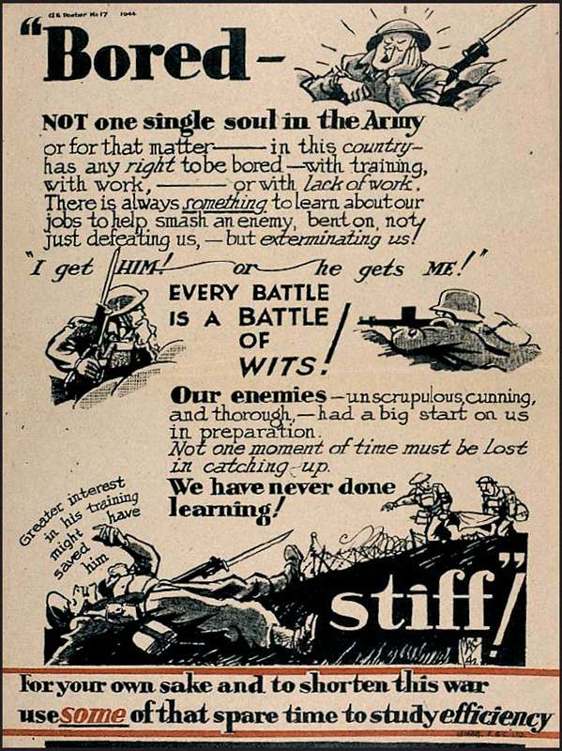

‘Bored – Stiff!’ A very interesting leaflet distributed among offices and factories and intended to reinforce the notion that training and preparation was crucial and that there was no excuse for idleness. Inattention and inefficiency was destined only to lead to disaster.

It wasn’t all commands and serious book learning of course. Each of the three services also published their own, less officious material. TEE EMM, the RAF’s Training Memorandum, was published on a monthly basis from April 1941. It enabled Bill Hooper’s legendary Pilot Officer Prune, who did everything wrong, to show the potential error of not doing things right. The inside back cover of TEE EMM Vol. 5. No. 3, June 1945, featured a stark cartoon showing simply a wooden cross bearing the letters ‘RIP’. Below the mound of grass into which the memorial was planted read the words: ‘His pilot couldn’t be bothered to strap himself in’.

On a lighter note a small classified ad at the bottom of the last column of text in the publication simply said:

STOP PRESS

Latest War Results.

2.21 a.m. Allies beat Germany

Each of the armed services published an assortment of information to keep those in uniform up to date with operational activities to do either with the arm of service they worked for or, on a more general basis, the political developments that might soon see the war come to a conclusion and them ‘de-mobbed’ back into ‘civvie street’.

Alongside TEE EMM the RAF also published an official fortnightly magazine called, appropriately, Royal Air Force. There was also Evidence in Camera, a regular RAF publication exhibiting some of the results of RAF Medmenham, the home of the RAF’s photographic reconnaissance unit operations (PRU) in the European and Mediterranean theatres.

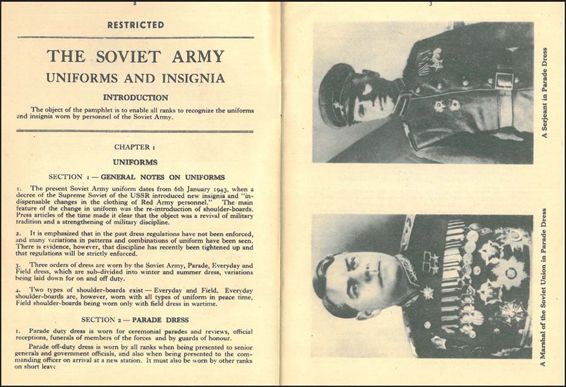

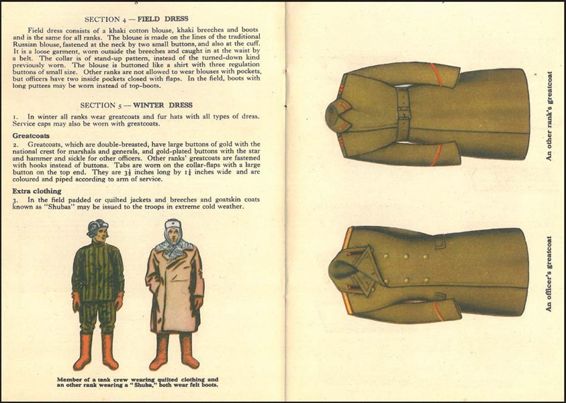

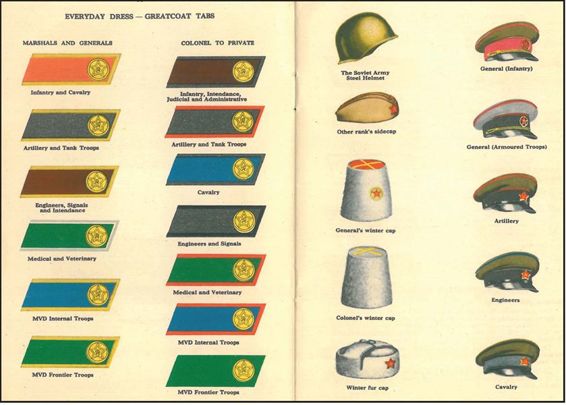

The Soviet Army Uniforms and Insignia 1950 superseded New Notes on the Red Army, published in 1944. A lot had changed in the relationship between the former Allies since then. As the Soviet Union consolidated its controlling grip over the states of the Eastern Bloc in March 1946 Churchill famously said: ‘From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.’ This was followed by the Berlin blockade over the winter of 1948/49, the formation of NATO and North Korea’s invasion of South Korea in June 1950. Although Russia and the West didn’t come to direct blows (discounting Soviet ‘advisors’ piloting MiG 15s against the USAF Sabres over Korea that is) the cold war and the opposing doctrines prepared for the worst. At this time the United States still enjoyed a lead in the possession of nuclear weapons but this advantage was to be shortlived.

Many other similar publications can be picked up relatively cheaply and all make fascinating reading as well as good investments for the future. Union Jack, the British Army’s own newspaper, initially covering operations in North Africa and the Middle East, where it amalgamated with Eighth Army News and later extended its coverage to cover operations in Italy and Greece, and Soldier, first produced by the War Office for Montgomery’s 21st Army Group in 1945, are but three publications associated with the army which can still be readily found. Soldier is still going strong nearly seventy years later! There’s Neptune, for Merchant Seamen, those unsung heroes of the Merchant Navy, and Flight Deck for the Fleet Air Arm and Navy News, reporting on all that happens in the Senior Service since 1954. The choice is virtually endless.

Armies, of course, train for war whether or not conflict is imminent. Like Boy Scouts, they have to be prepared. Consequently, the War Office carried on producing military training pamphlets instructing soldiers on how to use the weapons with which they were issued and what the likely equipment and composition of their likely enemies amounted to. Similarly, airmen and sailors learned the latest tricks of their trade by genning up on the latest published information. But, as fighting men got to grips with new uniforms and helmets, ironically based on those worn by their most recent adversary, the German Army, and pilots climbed into the cockpits of warplanes that, now devoid of propellers, were thrust skywards by powerful jet engines, they found themselves embroiled in a new war, the cold war. The West’s fighting men faced a daunting new enemy: the Warsaw Pact – the combined armed forces of the Soviet Union and its acolytes.

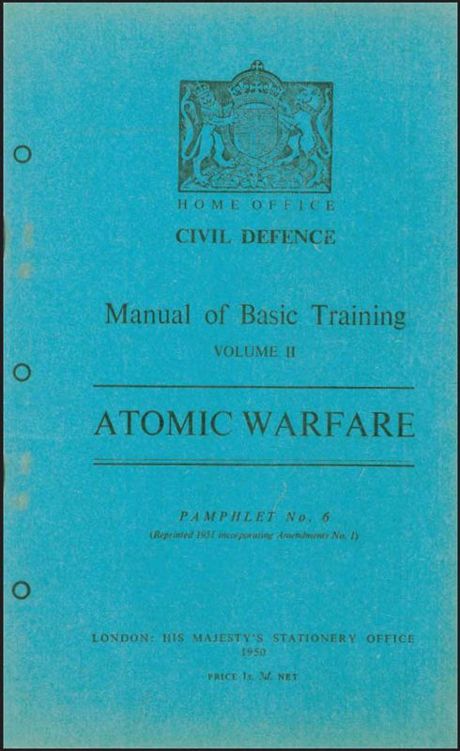

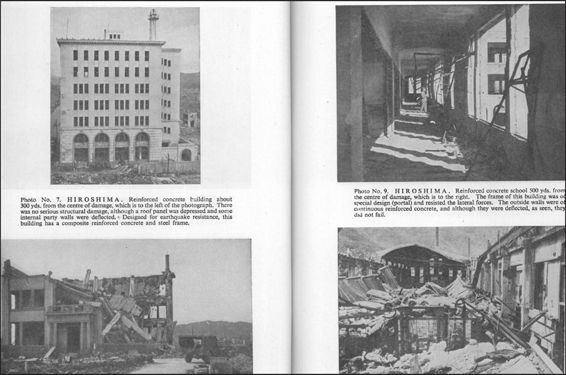

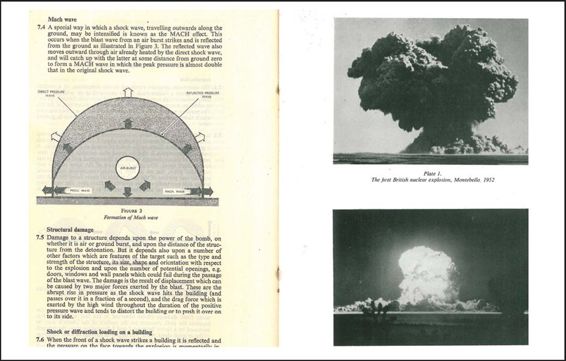

The year 1950 also saw the publication of a series of Manuals of Basic Training in Atomic Warfare published for the Civil Defence Service (CD). This is pamphlet No. 6. Disbanded in May 1945, the Civil Defence Corps was revived in 1949, and set about retraining members, some of whom had been members of the ARP during the Blitz, in the new techniques required to deal with casualties should nuclear Armageddon become a reality.

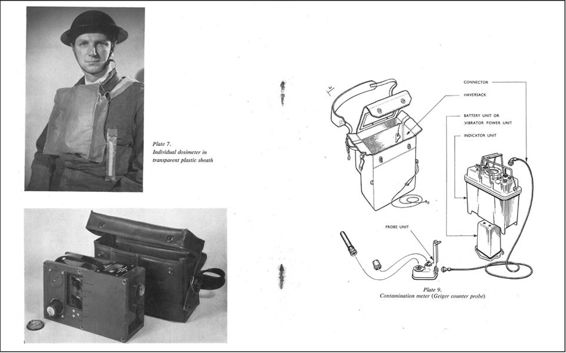

This manual, Nuclear Weapons, was used by those engaged in civil defence activities in Devon. Illustrated within is an individual dosimeter in transparent plastic sheath and a portable contamination meter. The Geiger-Müller counter ‘Meter, Contamination, set No. 1’ was the first such outfit widely distributed to those in civil defence. Using two 150-volt batteries, many such units remained in service until the 1980s. On 3 October 1952 ‘Operation Hurricane’, the test of the first British atomic bomb, was detonated off the Montebello Islands near Western Australia. Because British scientists had been involved with the American Manhattan Project the weapon was not dissimilar to Fat Man, one of the weapons dropped on Japan in 1945.

But there was another threat which everyone faced – a weapon of virtually infinite destructive power – the atom bomb. Of necessity, military training pamphlets got bigger and comprised numerous supplements and appendices as soldiers studied page after page of advice about how to deal with nuclear, biological and chemical threats. They learned that should nuclear weapons be used, they would go into battle after donning protective NBC outer garments, what the British troops called ‘Noddy Suits’ because of their pointed hoods that were reminiscent of the hat worn by Enid Blyton’s famous children’s character!

It became important to study the uniforms, weapons and tactics of the Soviet Army. I have an early post-war British Army training guide which details the uniforms and equipment of Soviet forces in my collection and this very rare, 1950 vintage publication is shown in this book. As it adapted to the new conditions of a nuclear stand-off, the RAF also had its work cut out. From 1956, Britain’s first operational nuclear weapon, the Blue Danube free-fall bomb, was carried by the V-bombers (Valiant, Victor and Vulcan) of the RAF’s strategic bomber force. Soon it was the Royal Navy’s turn when the Polaris submarine-launched ballistic missile system entered service in 1968 (the V-bombers were withdrawn from the nuclear role in 1969). From 1994 onwards, British submarines switched to the far more powerful, and no less controversial, Trident nuclear missile system. Fortunately for the compliers of military training pamphlets, there was suddenly a lot of new information for soldiers, sailors and airmen to get to grips with.

As with all militaria, collectors of printed ephemera should always try to purchase items that are in the best condition. Check that all the pages are intact and that bindings are sound. Avoid anything that has been scribbled on in biro – unless it is the authentic scrawl of the soldier, sailor or airman who was reading the publication in an operational context. As with all collectable books or magazines, first or early editions of military publications will command a premium price but offer far better rewards as far as investment opportunities are concerned. And, as is the case with all collectable items, especially delicate vintage printed ephemera, once purchased, such items should be conserved with care. And protecting your prized finds is the subject of the next and final chapter.