CHAPTER 7

Rust Never Sleeps is the 1979 album by one of my favourite musicians, Canadian singer-songwriter Neil Young and his band Crazy Horse. Young used the same title for his tour, signalling his determination to avoid artistic complacency and fatigue, even though, like all of us, he was getting that bit older and weather worn.

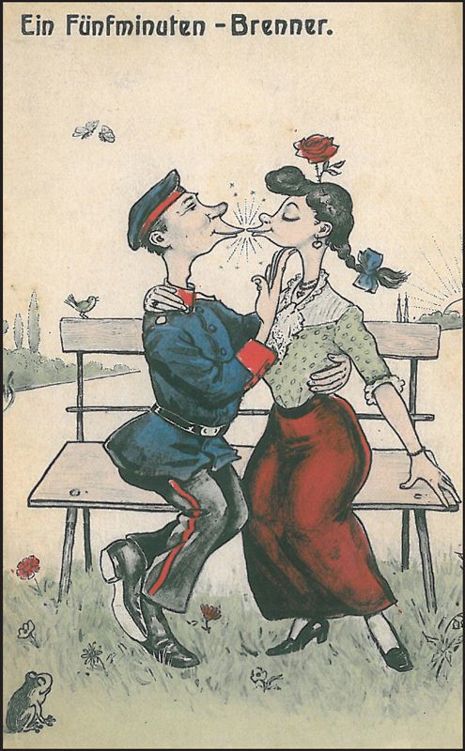

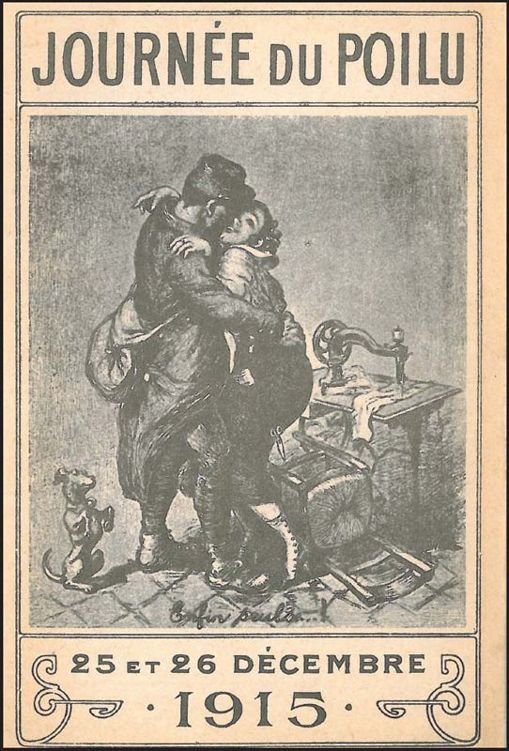

Ideally, postcards like these First World War examples – the German example: ‘A Five Minute Burner’, and the French: ‘Journée du Poilu’ (‘The poilu’s holiday’, about a poilu’s Christmas leave from the front), should be kept in special albums. After all, they’ve survived 100 years and it is the collector’s duty to see that they last even longer.

Using this, I have to admit, rather contrived link to the topic of this chapter – how preserve things in the best condition – I aim to show collectors some of the techniques they might employ to impede the inexorable degenerative process of decay. We won’t encounter ‘rust’ perhaps, although in the case of printed ephemera, ‘foxing’, which old documents sometimes suffer from, is a similar kind of oxidation, but the following advice will help enthusiasts keep their collectables in the best possible condition.

Entropy, that lack of order or predictability, leading to a gradual decline into disorder is, I’m afraid, the natural state of this expanding universe. We only ever see wine glasses smash. We never see them reassemble. Fortunately, some of this inevitable decline and fall can be slowed down at least. There follows some easy ways to start the redemption process and hold on to your vintage bits and pieces.

One of the best ways to prevent damage to printed ephemera is to make sure delicate paper items are stored correctly. Certainly, you should avoid displaying your paper memorabilia, books or pictures in direct sun or even artificial light. Whenever possible, also keep papers and books in containers. They are best kept in the dark.

Light is one hazard, damp is another – humidity will encourage mould to grow. And don’t keep your collection in an excessively warm place either, such as above a radiator, for example. It’s generally best to avoid fluctuating temperatures and aim if possible for a constant of 66 °F/19 °C.

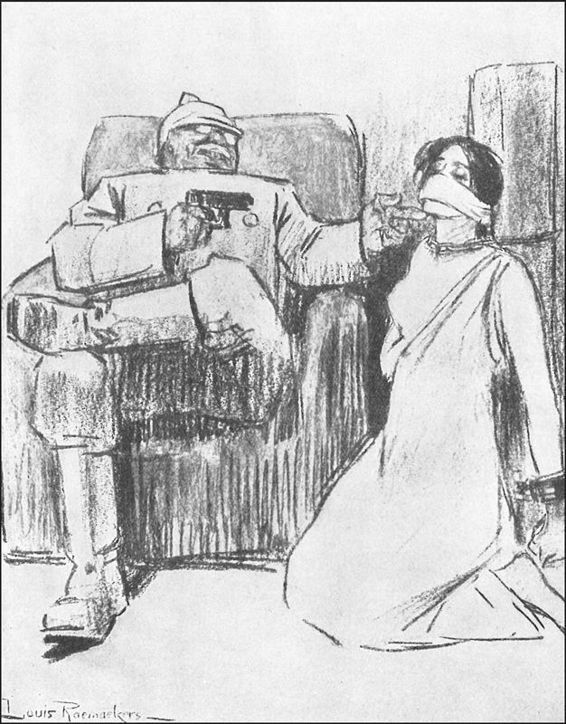

If you are lucky enough to possess an original lithograph of one of Dutch artist Louis Raemaekers’ xenophobic but none the less beautiful drawings such as this one, Aren’t I a loveable fellow?, care must be taken not only to store it in an acid-free archival folder, but that if it is displayed it is not exposed to direct sunlight.

Putting papers or books in places where they will come into contact with polluted or impure air, for example, near an opening window or in a room with a coal fire is also to be avoided. If you live with any heavy smokers, wait until they are out, out of cigarettes or asleep before removing your treasures from their display sleeves. We are all familiar with the qualification ‘from a smoke free home’ on eBay listings. Believe me, nicotine, tar, smoke and the components of the dangerous cocktail of about 4,000 chemicals in cigarettes all contribute to taking the edge off a pristine collectable. As they do with a smoker’s lung!

Booklice, members of the order Psocoptera, which contains about 3,200 species worldwide, can often be found hidden in the pages, often near the spine stitching and glue residue, of vintage books. Adult booklice can live for six months. Besides damaging books, they also sometimes infest food storage areas, where they feed on dry, starchy materials. They are scavengers and do not bite humans. Booklice prefer the dark, and they like temperatures of 75 to 85 °F. Because they need a high humidity in order to survive, storing books in cooler but perfectly dry places will prevent them from thriving.

Named because of the fox-like reddish-brown colour of the stains left by this affliction, ‘foxing’ is the term for the age-related spots and browning seen on vintage paper documents and books. It is thought that the rust chemical, ferric oxide, caused by the effect on certain papers of the oxidation of iron, copper, or other substances in the pulp or rag from which the paper was made, is the main contributor to this problem. As with the issue of booklice, high humidity also encourages foxing.

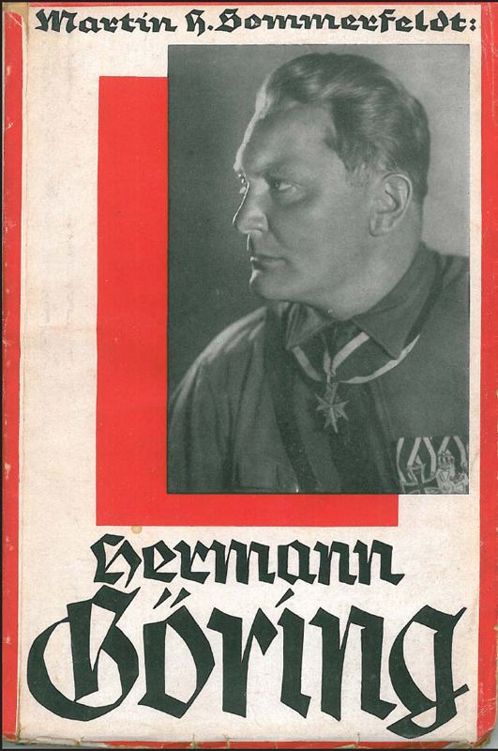

In the late 1930s paperbacks often came with removable dust jackets such as this volume about Hermann Göring, the last commander of Manfred von Richtofen’s famous ‘Flying Circus’ (Jagdgeschwader 1) and at the time of publication, in 1933, president of the Reichstag. At the time, the author, Martin Sommerfeldt, was the Minister of the Interior’s press officer. Collectors should search for examples complete with their original dust jackets.

However, paper is not only prone to attack from external factors. The very integral constituents of the product itself, the ingredients in its manufacture, can contribute to paper’s decay. Until the mid-nineteenth century, recycled rags were used as part of the paper manufacturing process. Later, increased demand led to the substitution of wood pulp for papermaking. But, unless it is chemically treated, wood pulp contains lignin, and over time this substance causes the paper to become acidic and subsequently discoloured and brittle, eventually disintegrating. We all know old newspapers are yellow in hue.

Even if your collection contains items high in lignified material, newspaper cuttings, for example, you can help prolong their life by storing them in lignin-free, or ‘acid-free’, containers and display boxes. Not all modern papers and card are lignin-free, and where possible these should be stored in acid-free archival quality storage wrappers and boxes.

Even if you can’t get hold of, or afford, acid-free archival storage materials, avoid wrapping items in newspaper, between sheets of cardboard or in brown envelopes. Good quality white paper and envelopes contain fewer impurities and should be used instead.

Vintage photographs shouldn’t be kept in the kind of commercially available albums used to exhibit family holiday snaps because these are likely to contain a high degree of impure substances. Colour photographs are the most sensitive items in your collection and prone to very rapid fading if not stored correctly. That is out of the light. They are best kept in chemically stable polyester, polythene or polypropylene enclosures but not in PVC, which will break down over time and emit hydrochloric acid as it goes brittle. Photographically safe paper, of low sulphur content, such as Glassine papers are best used as interleaving papers between fine photographs, art prints and in bookbinding. Such coverings, sleeves, are especially useful in protecting vintage ephemera from damage from the acids resulting from handling.

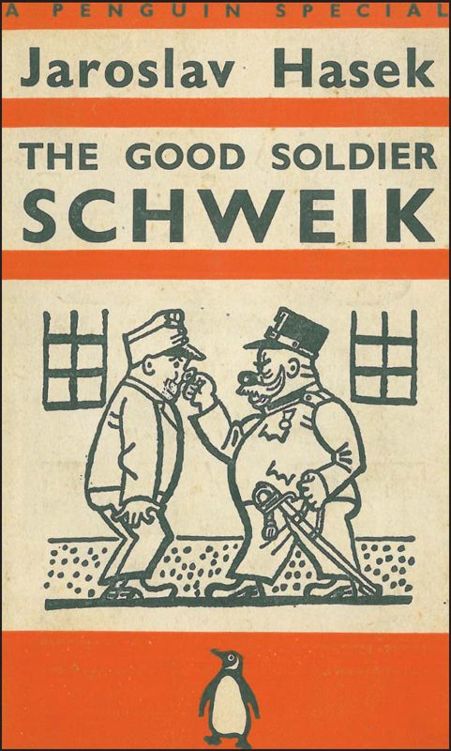

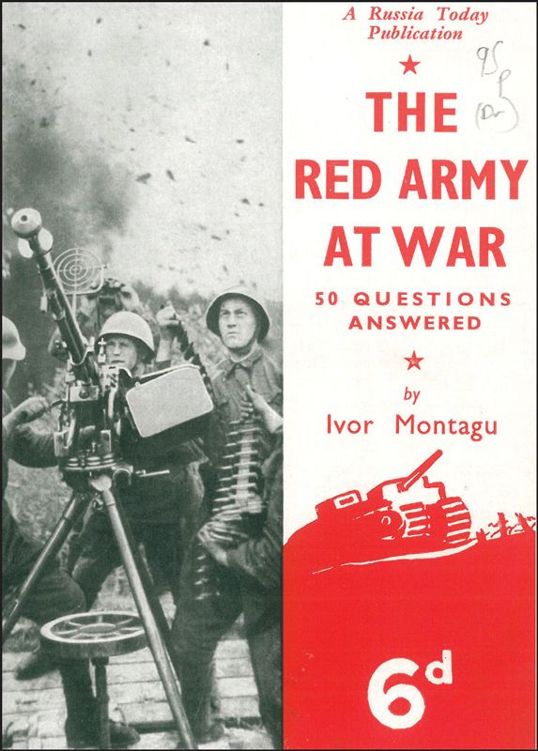

Penguin Specials are becoming more and more collectable. To ensure their preservation they should be kept in stable environments – so not in the loft or garage from which when removed they will generally be exposed to dramatically increased temperatures. The Good Soldier Schweik recounts the adventures of a malingering Czech soldier caught up in world events since the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria.

Never use adhesive tape (Sellotape, etc.) or sticky labels on items you wish to keep. In time the adhesive will migrate into the paper, staining it and leaving a sticky residue behind.

I’m often asked why sunlight or more properly ultraviolet light (UV) causes colour to fade. Well the technical term for such bleaching is photo degradation. The light-absorbing colour particles called chromophores, the part of a molecule responsible for its colour, are present in all inks and dyes and the colour we perceive is a result of the amount of light that is absorbed by these components in a particular wavelength. Ultraviolet rays can break down the chemical bonds of chromophores and thus fade the colour reflected from an object. Some things are more prone to fading, such as dyed textiles, certain inks and paint pigments, particularly reds. Objects that reflect the light more, repelling dangerous ultra violet, are naturally less prone to fading.

A measure known as the Blue Wool Scale calculates and calibrates the permanence of dyes. Traditionally, this test was developed for the textiles industry but it has now been adopted by the printing industry as measure of light fastness of lithographic and digital inks.

The process involves taking two identical samples and placing one, the ‘control’, in the dark. The other sample is placed in the equivalent of sunlight for a three-month period. A standard blue wool textile fading test card is also placed in the same light conditions as the sample under test. The amount of fading of the sample is then assessed by comparison to the original colour. A rating between 0 and 8 is awarded by identifying which one of the eight strips on the blue wool standard card has faded to the same extent as the sample under test.

‘Permanence’ or ‘fastness’ refers to the chemical stability of the pigment in relation to ‘any’ chemical or environmental factor, not only light but including heat, water, acids, alkalis or attack by mould.

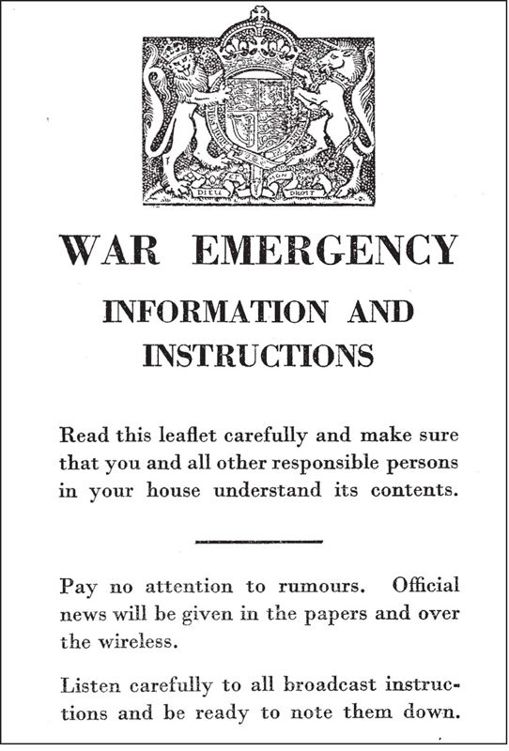

Often overlooked, the myriad War Emergency leaflets which dropped through letter boxes during and immediately after the Munich Crisis in 1938, and which continued throughout the war, are hugely important historic records. They are also very fragile and in need of careful conservation.

Founded in 1846, the Smithsonian Institution, located in Washington, DC, is the world’s largest museum and research complex, consisting of nineteen museums and galleries, a National Zoological Park, and nine research facilities. Its Museum Conservation Institute (MCI) is considered one of the world’s leading authorities on conservation and combines state-of-the-art instrumentation and scientific techniques with a unique knowledge of materials. The Smithsonian publishes a set of guidelines to everything from archival document preservation to fabric conservation and I can’t recommend this institution highly enough.

All this talk of ‘chromophores’ and ‘photo degradation’ might sound a bit highfalutin and to some might suggest a degree in bio-chemistry is required in order to keep collectables in good order. But to be honest, day to day conservation, the maintenance of the average collection, is not rocket science. Here are my top ten tips:

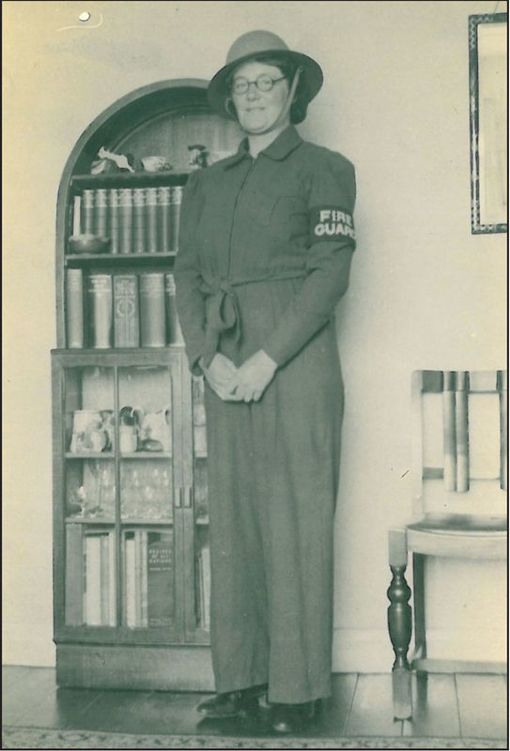

Period photographs are an important part of the historic record and should not be discounted. They can also be purchased relatively inexpensively. Fortunately, being printed on black and white bromide paper, photos like the two seen here, of a wardens’ post and beaming fireguard, will survive without fading for generations to come.

1. Store everything neatly in a clean dry atmosphere and avoid moving things from warm to cold places – this will encourage mould growth.

2. Keep things clean – wear linen gloves when handling very old or delicate documents.

3. Keep printed items and photographs, especially colour ones, away from direct sunlight.

4. If you want to frame and display vintage items, don’t hang them on walls, or place them on shelves, directly opposite windows.

5. Ideally keep things flat not rolled.

6. Don’t wrap things in newsprint or brown paper – if you don’t have access to archival, acid-free paper, use good quality white paper or card.

7. Don’t store photographs or old documents behind plastic sheets in self-adhesive picture albums – use ‘A-sized’ folio display sheets as used by graphic designers.

8. Keep old books upright or interleaf them with bubble wrap to avoid their spines cracking.

9. If packaging lots of items for storage, try to stack together items of the same size. For example ‘foolscap’ documents, common in Britain and the Commonwealth before the adoption of the international standard A4 paper in 1975, are 8.5 by 13.5in (215.9 by 342.9mm) and if stacked on top of A4 is 8.3 by 11.7in (210 by 297mm) will suffer from creasing damage.

10. Make sure you have an accurate inventory of what you have, its provenance and where it is stored!

Many original period illustrations are executed in a kind of opaque water colour known as gouache. British firm Winsor & Newton has been making such paints since founders Henry Newton and William Winsor established the firm back in 1832. When asked how ‘fugitive’ some designer gouache colours are they explain thus:

The fading of a colour is due to the pigment and the methods which are used in painting. The permanence of a colour is described by Winsor & Newton using the system of AA, A, B and C. AA being Extremely Permanent and C being Fugitive. Fugitive means ‘transient’, some fugitive colours may fade within months. For permanent paintings it is recommended that only AA and A colours are used as these are not expected to fade. Light Purple has a B rating and Parma Violet a C rating, fading over a 10 year period would not be unexpected with these colours.

As far as lithographic inks are concerned, the inks used for posters, magazines and the colour plates in books, magenta and yellow tend to fade faster than black and cyan. This is why we often notice that advertisements and posters left in shop windows exposed to natural sunlight soon adopt a distinctly blue hue.

In the last thirty or so years, the major photographic manufacturers have developed more stable dyes for colour photographs and the good news is that these modern photographic prints will only fade a little in as long as 100 years, if kept in average home conditions – but, again, not in direct sunlight or bright tungsten light.

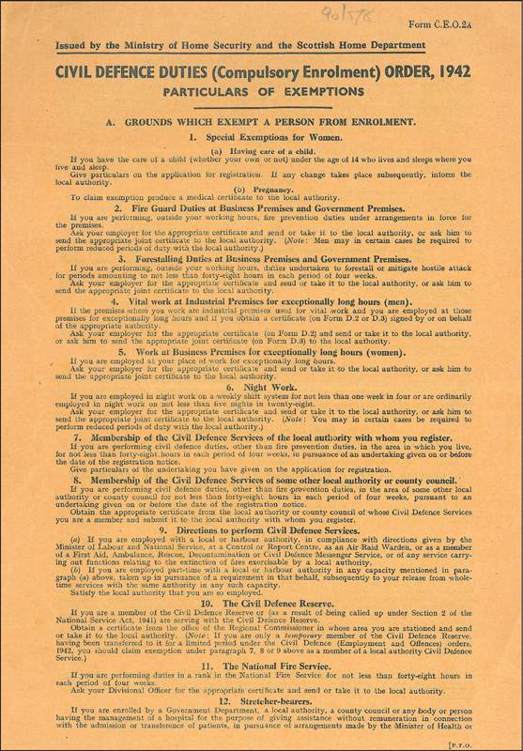

Some documents, such as this one detailing the compulsory enrolment for Civil Defence Duties and the ways those on the home front either unfit for military service or in reserved occupations were eligible for exemption, were printed on cheap newsprint and are very delicate. Newsprint is made using untreated, ground wood fibres with impurities remaining after processing that include resins, tannins and lignins, which promote acidic reactions when exposed to heat, light, high humidity or atmospheric pollutants. This causes the paper to become brittle and deteriorate, often rather quickly. Careful storage in archival display sheets is recommended.

Though manufacture and processing of this excellent material ceased in 2010, Kodachrome was introduced by Eastman Kodak in 1935. Transparencies (‘slides’) exposed on this non-substantive, colour reversal film were a staple of still photographers for decades and for many years it was mandatory to use Kodachrome for images intended for publication in print media. Fortunately, this film always featured very stable dyes, meaning Kodachrome images will last decades with very little fading – especially if mounted slides are not used in a slide projector too regularly. Even sixty-year-old Kodachrome slides look nearly new.

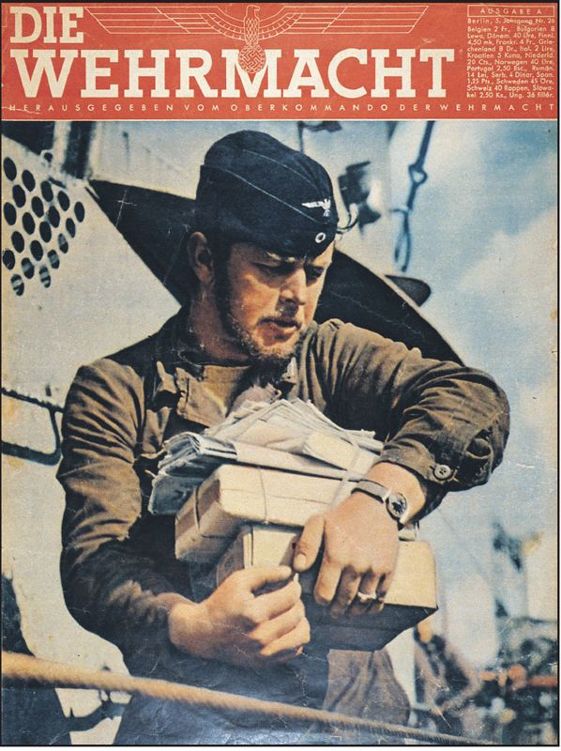

The Third Reich led the way in the production of colour magazines. Now, over seventy years since they were printed, these publications are not as robust as they once were. Ideally, they should be stored in archival sleeves or envelopes and supported by acid-free stiffeners.

Try to avoid writing on the surfaces of vintage documents and if you do use pencil which can be erased.

Similarly, because it uses thirteen layers of azo dyes sealed in a polyester base, Cibachrome prints will not fade, discolour or deteriorate for an extended time. Like many other collectors, I got into the habit of making Cibachrome copies of transparencies and printed items and these have proved perfect for display purposes. Sadly, in 2012, in response to declining market demand attributed to the expanding popularity of digital photography, manufacturer Ilford announced the final production run of Cibachrome (now called Ilfochrome Classic).

But there it is, aside from monochrome (black and white) bromide prints, which possess almost limitless qualities of permanence, Kodachrome and Cibachrome, two of the best colour photographic materials, are now lost to us. Only time will tell just how stable some of the modern inkjet prints will be but they should keep their colours and vibrancy much longer than colour photo prints. Many have been ‘lightfastness’ rated for more than 100 years. Be warned, though, prints made on some papers can take several days to finally stabilise – a phenomenon known as ‘short-term colour drift’. It occurs mainly with cheaper dye inks and can lead to uncertainty about what the final print colour balance will be. Regardless of which type of ink your printer uses, high-quality, acid-free papers are more stable than standard papers, which is why they are used for all archiving and fine-art applications. Pigment inks are slightly more stable than most dye-based inks, although the differences have been reduced with the introduction of highly stable dye ink sets in recent years. To obtain the maximum stability from your inkjet prints, give each print a minute or two to dry then cover it with a sheet of plain paper. Leave the covered print for at least 24 hours before framing it or storing it in an album. Inkjet prints last longest when framed behind glass or encapsulated in plastic (‘laminated’) to protect them against airborne pollutants. This is also a good way to protect traditional photos against light, dust and moisture – as well as airborne fungal spores.

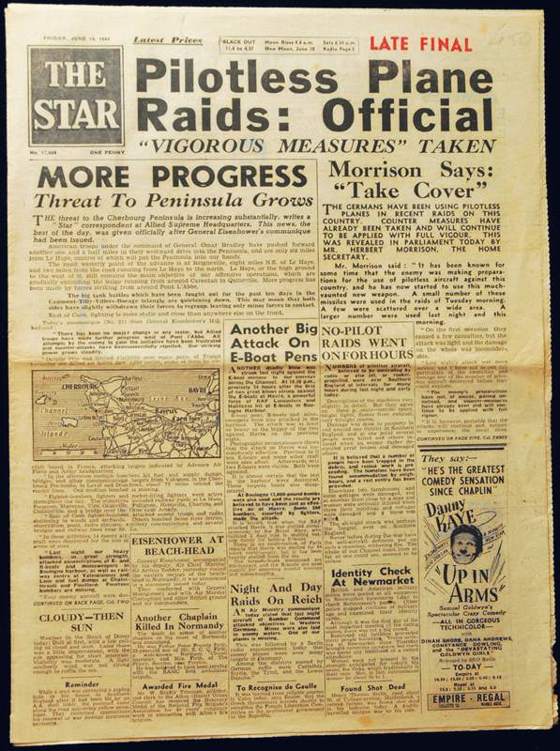

Original newspapers provide really interesting collectables and they are fast becoming an investment. Truly ephemeral and never meant to be kept, they were printed cheaply on paper rich in lignin, which might make wood stiff and trees stand upright but also makes newsprint brittle. Consequently, many of those that were saved have long since turned to dust. ‘Pilotless Plane Raids: Official’, the Star, Friday, 16 June 1944 – barely ten days after D-Day and Britons discovered that Germany still had secrets up her sleeve and the V1 was just the first of them.

Airborne fungal spores might sound a bit alien, even frightening, but we are all familiar with dust. Not to be confused with atmospheric dust which is the product of geological ‘saltation’, tiny eroded particles transported by the wind, which end up in the troposphere and are eventually deposited back on Earth, domestic dust, dust in homes, offices and other human environments contains small amounts of just about everything. Plant pollen, human and animal hairs, textile and paper fibres, human skin cells … you name it, all contribute to the domestic dust problem. And if you’ve got an open coal fire – don’t get me started.

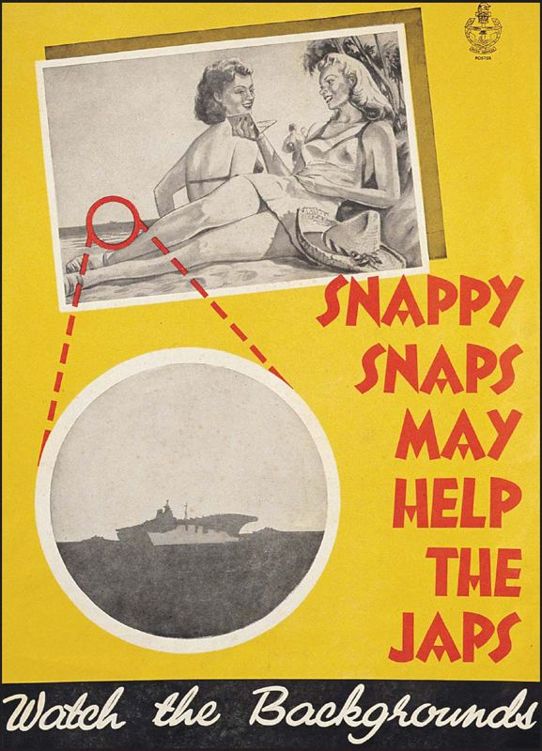

‘Snappy Snaps May Help The Japs Watch the Backgrounds’. Although colour leaflets were generally printed on better quality material than newsprint and consequently less prone to acid attack, lithographic inks are still ‘fugitive’, that is subject to colour fade if exposed to natural light.

So, my last bit of advice is simply this, keep everything covered. Either in drawers, display cases, transparent portfolio sheets or even simple cardboard boxes, but keep things covered!

And talking of keeping things covered, there’s no point in taking the time to maintain your valuable collection in tip-top condition if, by no fault of your own, it suffers damage or theft. It’s easy to purchase collectables insurance and most of the established insurance companies and independent brokers will offer comprehensive cover of one kind or another to suit your needs.

First off you naturally need to estimate the value of your collection and determine the amount of insurance you might need. Don’t forget, you need to insure your collection for ‘replacement value’ – what it would cost if you had to search for similar items in good condition and buy them all over again on today’s market. If your collection is even more than a few years old it will have almost certainly appreciated in value since you first began acquiring items. Recently in Britain, home front, especially Home Guard and Air Raid Precautions (ARP) items have greatly increased in value. You need to compile and maintain an inventory of your collection and if you have receipts for certain expensive items retain them to provide proof and expedite claims in the event of a loss. Keep a copy of your inventory in a secure, secondary location from where your collection is housed (such as a safe deposit box). A good method to further accomplish this is to email the inventory to yourself and then you can access it from any computer. If you have suffered loss you must contact your insurer’s claims department as soon as possible, stating the type and location of loss, the date of the loss and the claim amount. You will need to have your records on hand when contacted by the claims adjuster, and any photographic or video evidence of your collection and any police reports which will provide a crime number and greatly help to substantiate your claim will be of enormous help. When taking photos or video of your collection, be sure to concentrate on any and all markings or details that will help authenticate particular items.