Chapter 6

Yann Le Bohec (Translated and Edited by Christopher Matthew)

The Romans of the imperial period practised several religions.1 In one they honoured the traditional gods such as Jupiter, Juno, Minerva and Mars; in another they celebrated the emperor; still another addressed the divinities of the provinces, or the so-called Oriental gods; and finally they honoured the dead. This last type of cultic activity is often neglected in modern scholarship. Yet this religion had its own organization, with its own deities, myths, and rites. In the Roman Empire, almost the same treatment was reserved for all of the deceased, whether they were military or civilian, but specific differences are nevertheless noticeable. Firstly, unlike in the modern era, the Romans rarely erected monuments as war memorials, which became so widespread in modern Europe – especially after 1918. Some archaeologists have detected a memorializing construction of this type at Adamklissi in Dobruja, in present-day Romania.2 On this site, Domitian had earlier erected a monument called ‘The Triumph of AD 89’ to commemorate the dead, which was destroyed in the time of Trajan, and which could indeed be compared to a ‘monument to the dead’. An altar also exists at this site, listing the names of thousands of soldiers who lost their lives in battle in this region. In AD 109, Trajan added an enormous trophy (tropaeum), better known as ‘the mausoleum of Adamklissi’, and scholars have wanted to interpret this building as a tribute to the dead soldiers of this conflict. This was, however, actually a monument to a god; the emperor had dedicated it to Mars Ultor (Mars the Avenger) in honour of the Romans killed in the wars in Dacia.

The Pantheon of the Dead Soldier

The cult of the dead among the Romans was organized around a simple pantheon in the beginning, which became more complex thereafter. It included the souls of the dead, gods, occasionally the deities of the East and sometimes, as the centuries progressed, Christ. By tradition, the Romans honoured the souls of the dead, called Manes from an old Latin word which meant ‘the Benevolent’; the Romans referred to them by this antiphrasis in order to appease them, because they feared them.3 Indeed, it was believed that the Manes could be very vindictive and harmful if the living forgot to worship them.

Some important gods turned away from their regular occupations in order to protect the dead – at least that is what the relatives of the deceased requested them to do – mainly the Muses4 and the Dioscuri (the two sons of Jupiter, Castor and Pollux).5 A unique phenomenon occurring only in military contexts is attested: the ancient Romans, when they went into battle, believed that they could be inspired and protected by what could be termed ‘ghosts’, or ‘shades’: the souls of great ancestors.6 Many generals, for example Scipio Africanus, claimed that they were ‘accompanied’ by ‘role-models’ who instructed them in virtus (service to the state) in both its civil and military forms (hence the meaning is derived from the word for ‘courage’); they also gave them lessons in military discipline (disciplina). In a related manner, it is believed that Alexander the Great had a major influence on many famous conquerors: for example, Caesar and the emperors of the Severan dynasty, especially Severus Alexander. As for the private soldier, it is probable that he hoped to profit from the protective company of the souls of his family.

As is known, early Roman religion left little hope for the dead: it provided them only a mediocre ‘afterlife’ in the grave.7 In consequence, when proselytizers of foreign cults promised those who would participate in such cults a more pleasant afterlife, they garnered adherents, who had eschatological (afterlife) hopes for a meaningful life after death.8 Modern scholars have given the name ab Oriente lux (‘the light that comes from the East’) to these cults, but this is currently criticized because such cults and rites are characterized by a great diversity. Yet they did have two things in common, being called ‘mystery cults’ and offering a religion of ‘salvation’ to adherents. The faithful received an initiation, during which myths and secret rituals for the initiated were revealed to them; this allowed them to benefit from life after death. Their practice was quite compatible with the other official religions, the worship of the traditional pantheon, the imperial cult and the deities of the provinces. Three Eastern deities played a special role in this regard.

Of the ‘foreign’ cults which spread to Rome, neither Cybele nor Isis had much success with the military. Amongst the soldiers, it was the cult of Mithras which attracted the most followers. This god probably originated in Iran, and he was represented dressed in the fashion of his country, in trousers with a cap, and is shown in the cult’s iconography energetically slaughtering a bull, whose head he holds by the nostrils; this animal symbolized the cosmic evil that the god sought to eradicate (see Figures 8.1, 8.4). Mithraism was served by a hierarchical clergy, some members of which were called milites (soldiers). The military played no part in the spread of Mithraism. Moreover, the extent of military participation in the cult has been exaggerated by modern scholarship. Having said that, it is difficult to calculate exactly the proportion of civilians to soldiers which practised the cult. Additionally, their places of worship, called mithraea, occupied very small spaces, which could normally only accommodate about twenty faithful. Scholars of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw this god as highly significant, to the point that he was sometimes described as a possible competitor to Christianity. Recently, R.L. Gordon has strongly qualified this idea,9 and his conclusions are sound.

Some historians have considered that Christianity was the last of these ‘Eastern religions’ for three reasons: Christianity came from the East, its theology was based on a dead and resurrected God, and it promised a pleasant afterlife for the faithful who had adhered to standards of good behaviour here on Earth. Certainly, Christianity had an influence on the military, but not greatly in the first two centuries ad.10 Christianity spread more among the armies stationed in the eastern part of the Empire than in the western, as evidenced by a centurion named Cornelius in apostolic times,11 and Legion XII Fulminata of Cappadocia, under Marcus Aurelius,12 up to the Theban Legion during the Tetrarchy.13 The first undisputed historical event is reported by Tertullian;14 it occurred in Rome, among the Praetorians, probably in AD 211. Soldiers were lined up to participate in a religious ceremony, obviously polytheistic, and there were Christians in their ranks. One of these refused to celebrate ‘heathen’ rites and threw his wreath (which was probably part of the ritual) on the ground. He was sentenced, probably to death. Subsequently, military martyrs are attested several more times, especially in the time of Diocletian and in Africa.15

The Place of the Dead Soldier

The cult of the dead had specific places, the necropoleis, for its rites. Scholars, laypeople and archaeologists, however, do not agree on the places where soldiers were buried. Some scholars argue that military cemeteries did not exist,16 because the state did not intervene to organize or protect them. Responsibility for the burial belonged to the private domain. An individual bought a parcel of land and prepared his grave; if he neglected its care, his heir took charge of it. The authorities only intervened if there had been a dispute over the property or impious conduct towards the grave.

The views of the inhabitants of the Empire seem to have been very close to the interpretations of legal scholars in this matter. The best proof is that since the Latin language does not have a word for a necropolis, the Romans had to resort to a Greek word (κοιμητήριον, koimeterion). Moreover, the word νεκρόπολις (necropolis) seems to have been very little employed,17 except in Alexandria in Egypt.18 Latinization of koimeterion (as coemeterium) is not very common; it is late when it does occur, and its usage appears to have been limited. It seems to have had particular success in Africa, where it appears in the works of Tertullian,19 St Cyprian,20 Optatus (Optate) of Milevis,21 and St Augustine.22 It is also present in epigraphy, but particularly in Rome,23 Ostia,24 Velletri,25 Florence26 and in Cirta (Constantine) in Africa.27 The translation dormitorium (‘sleeping place’) appears only once, in a glossary,28 as a metaphor. In the revised edition of the dictionary of L. Quicherat, É. Chatelain mistakenly took the word sepulcretum as a synonym for cemetery; the Roman poet Catullus uses the term in the plural, in a context that is not confusing, to designate a person who lives from looting offerings deposited near graves.29 It is therefore necessary to understand sepulcretum in the sense of an isolated burial, and not a necropolis.

Archaeologists find that graves were grouped and located outside urban centres.30 The dead could not live with the living. These groups of funerary monuments were indeed cemeteries, especially as they were sometimes enclosed31 and beautified by gardens.32 Distinctions were made between the cemeteries where the remains of soldiers killed in action were deposited and those which housed men who had died a natural death.

A fact that will surprise the reader of the twenty-first century is that fallen soldiers did not receive a particularly honorific treatment – far from it.33 After a battle, the victors tried to heal their wounded (who often died as hygiene was poor and dirty dressings caused secondary infections). The Romans collected their dead with a minimum of respect, and then buried them summarily. If the Romans were victorious, the bodies could be interred, as they would have been near their camp. One interesting inscription suggests that the remains of the soldier were brought back to his homeland (there is no evidence for a cenotaph):34

‘D(iis) M(anibus). | Aur(elio) Iustino, militi | leg(ionis) II Ital(icae), (obito) in exp(editione) | Daccisca, an(nis) XXIII. | Aur(elius) Verinus, uet(eranus), et | Mes(sia) Quartina, pa | rentes, fecerunt.’

‘To the spirits of the dead. Aurelius Justinus, soldier of Legion II Italica, died in the expedition to Daccisca, at the age of twenty-three. His parents, Aurelius Verinus, a veteran, and Messia Quartina, his mother, had this monument made.’

It is not known what the nature or date of this expedition to Daccisca was, although it is mentioned in another inscription.35 Modern editors of the two epigraphic texts have thought this might relate to Dacia, but the two forms of spelling used by the inscriptions, which are very similar to each other – Daccisca and Dacisca – suggest another region, still unknown. From the time of Marcus Aurelius, Legion II Italica had been stationed in Noricum, a province that corresponds to parts of Austria, Bavaria and Slovenia. As for the relatives and friends, they merely indicated that the deceased had died in combat; the formula desideratus in acie (‘died in battle’) was also used.36

In the case of a defeat, on the other hand, the treatment of the dead was more expeditious. Two examples are quite well known: from Lake Trasimene and the Teutoburg Forest. After the Battle of Lake Trasimene in 216 BC, which was actually an ambush by Hannibal’s Carthaginians, the bodies of the Romans killed were burned; the cremation ovens were found north of the lake at Tuoro, between Borghetto and Passignano.37 In AD 9, the soldiers under Varus killed in the Teutoburg Forest, another ambush, were deprived of burial,38 abandoned on the ground by the victorious Germans, who wanted to show their superiority and sought to discourage the Romans from recommencing a war of conquest. The army of the vanquished had been annihilated and their more fortunate enemies deliberately left them to rot on the ground. In Roman belief, the dead were thought to be unhappy (no one believed in a happy afterlife where they received their just deserts), and only rites, the first of which was burial, brought the deceased a little consolation. In AD 15, the soldiers of Germanicus found the bones of their unfortunate colleagues, and he had the remains, which had been scattered in heaps and without special care, buried in a tumulus.39 This burial of the corpses of the Teutoburg legions was seen by the Romans as a means of repairing the Varian disaster.

Soldiers who died of old age or sickness in their garrison town were subject to almost the same treatment as civilians. Special necropoleis do not appear to have been reserved for them, although it seems that their presence in some cemeteries was more pronounced than in others. Possibly, however, the cemetery excavated in Am Wiegel, west of Haltern in Germany, was not open to civilians.40 As a rule of thumb, the deceased soldiers were buried first along the roads leading from their camp or a nearby city, and then further and further away from and behind this first line of graves, which gave these clusters of burials rounded forms over time. As a result, the military was largely in the majority in burials at the exits of camps. They were in a mixed situation elsewhere, buried alongside civilians. This situation has been well studied in the case of Mainz.41

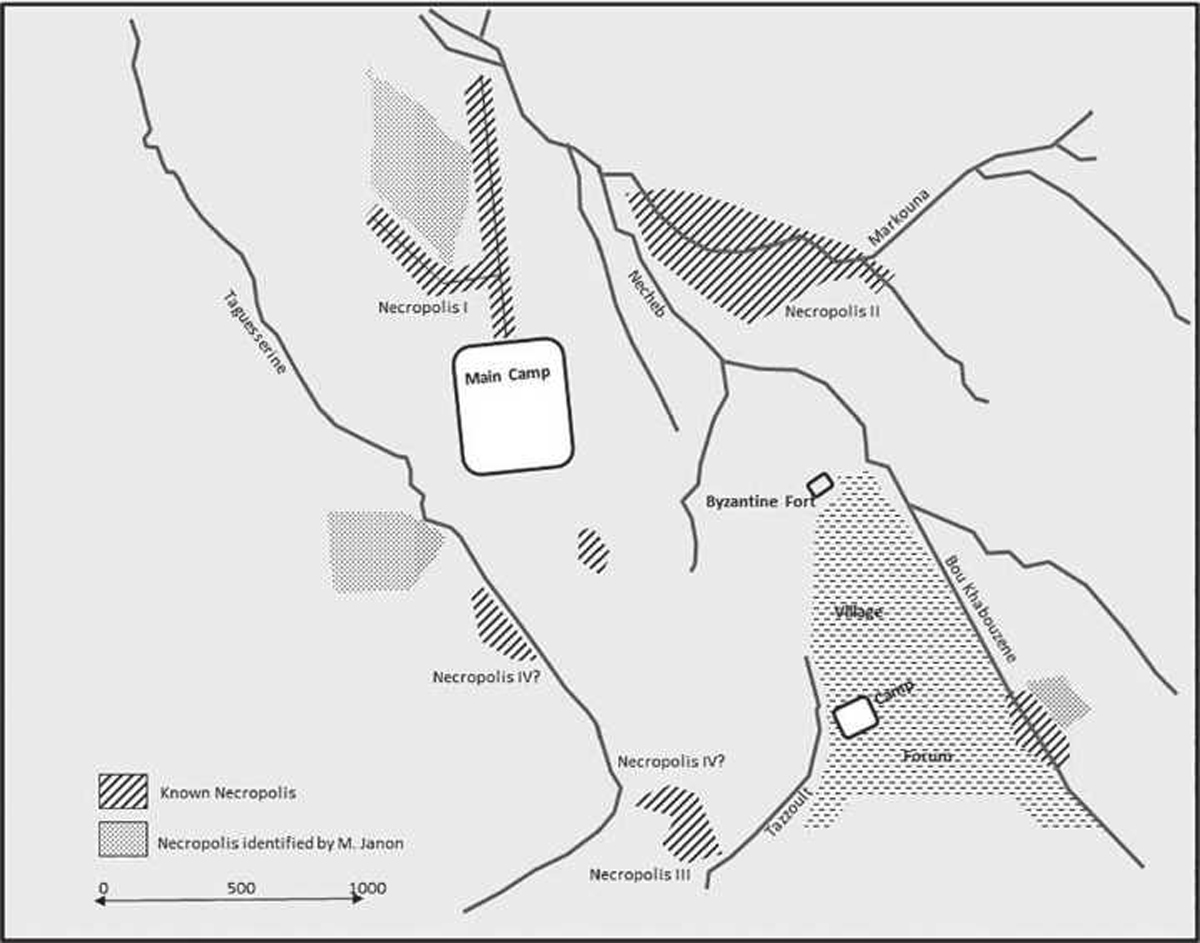

At Haîdra (Ammaedara) in present-day Tunisia, a camp was occupied from AD 6 until AD 75 at the latest. The military graves lined the main road that ran from the camp to the north-east, towards Carthage, the capital of the province. Lambèse provides a more interesting case (see Figure 6.1). In the second and third centuries AD, this site, located at the northern foot of the Aures in Algeria, was both the capital of Numidia – a province officially created at the end of the second century AD – and the headquarters of Legion III Augusta. The main camp has provided the largest collection of military epitaphs that is known for the Empire.42 It was in use from about AD 115/120 until the beginning of the fourth century. There were at least three necropoleis, and possibly four, on this site. The majority of the soldiers were buried in areas which ran north from the main camp towards Cirta (Constantine). They were also buried in reasonable numbers, alongside civilians, in an area that was further east, north of the city, along the wadi Markouna.

Figure 6.1: The necropoleis of Lambèse (based on Le Bohec, 1989: 108).

Monuments to Dead Soldiers

To practise the veneration of a dead man, one had, of course, to be able to locate his grave. For this purpose, and to answer a concern about locating the funerary place, it was marked by a monument. These memorials for dead soldiers were similar to those erected for civilians, but there were some significant differences.43 Funeral rites followed a general pattern,44 but they did change according to the date, the province and the social rank of the deceased. As a general rule, a vigil was held over the body of the deceased soldier, which was displayed to friends of the family, and then purified. The corpse was washed and anointed with ointments and perfumes. If the deceased had been a Roman citizen, he was dressed in his toga. Family members, friends and professional mourners attended the funeral procession, and the body was taken to a necropolis, where it was either buried (inhumed) or cremated, in accordance with the deceased’s own traditions. For cremation, the body was burnt on a pyre, the ashes placed in an urn and deposited in the earth. The inhumed were placed in the ground, either directly or in a sarcophagus of wood or stone – those of wood were deposited in the ground like urns, and those of stone often sculpted and placed prominently. Other rites were practised after the funeral.45 The dead were thought to exist unhappily in their tombs, and funerary rites were performed to ensure that they passed a less wretched afterlife. Monuments locating the point of burial allowed his family to locate the site and celebrate rites at the tomb, essentially consisting of food offerings.

The deceased departed for the afterlife with drink and food (these offerings will be further discussed below), and were believed to find a little life and happiness only at the time of the celebration of rites upon the grave. To provide for an easier existence in the underworld, the relatives deposited meals at the grave, along with one or more lamps, which gave the deceased a light in the darkness, and money to pay Charon, the ferryman of the souls across the River Styx in the underworld. The dead were supposed to live both in the tomb and in the underworld. This ritual seems neither logical nor consistent in the eyes of a person of the twenty-first century, but these contradictions did not disturb the ancient Romans. Small jars of vinegar allowed the dead to renew and anoint their body.

After the funeral, the soldier’s relatives, on fixed dates, would meet at the grave to pour libations and hold a banquet. A part of the food was left for the deceased, and water, thanks to a pipe, went through the ground to the grave. The living made food offerings and shared a meal, bringing food (meat, fish, vegetables, fruits, honey), drinks (water, wine, milk) and flowers. These meetings were morally obligatory during celebrations that were held from 13–21 February, with the dies parentales (‘parental days’, the Parentalia festival), which ended with the feralia (offerings were brought to the tombs) and the caristia (in this case, the dead of the family were invited to their former home for a banquet). The rosaria (or violaria) were also celebrated between 18 and 21 February.46 On 9, 11 and 13 May, the Lemuria rites were renewed (although, in this case, the father of the family asked the Manes to leave the house). Finally, the dead came out of the earth (mundus patet, it was said) on 24 August, 5 October and 8 November. Note, however, that these celebrations are absent from the famous military calendar of Dura-Europos: no specific rite was celebrated by or for these soldiers.

Legally, the deceased and the Manes (souls of the ancestors) owned the piece of land on which the grave had been dug; it could not be part of an inheritance, but remained the property of the occupant, and it was not possible to sell it or to bury a different body within it.47 Sometimes the grave inscription specifically includes this prohibition. In addition, the inscription also gave the dimensions of the piece of land, to avoid later encroachments upon it.48 In other cases, the inscription frequently specified the inalienability of the tomb through the widespread use of the abbreviation HMHNS or HMSLHNS:49

‘H(oc) m(onumentum) s(iue) l(ocus) h(eredem) n(on) s(equetur).’

‘This monument and its location will not be part of an inheritance.’

In case of infringement, the culprit was liable to a fine, whether or not mentioned in the inscription.50 The heir (or the heirs) assumed responsibility for the burial,51 as will be seen later in some inscriptions.

In theory, the Roman state and local authorities did not intervene in matters relating to graves. Heirs, however, had a legal obligation to ensure, as has been noted, that the right of property and the locus religiosus (sanctity of the burial place) was observed.52 Another concern for the heir was that spoliation and alterations were forbidden, except, sometimes, if the grave was surrounded by a large piece of land. In this case, a limitation of the area could be considered. Many actions with respect to the vicinity of the grave were not permitted, and municipal magistrates were responsible for overseeing cases which involved the opening or profanation of the tomb, the burial of other people next to the deceased, the displacement of the body and the erasure of the inscription. They also had to be present during the internment of the deceased and to ensure the exclusion of intruders. Finally, if necessary, they controlled acquisition, transmission and, in rare cases, re-use.

From the point of view of architecture, the monuments can be divided into several categories. The main types were constructed in Rome,53 where the living erected for their dead altars with garlands, columns and pilasters, facades with or without coronation, and with busts or various representations of the deceased. There were also tumuli, pyramids (such as the famous pyramid of Cestius) and exedrae (‘seat-tombs’). Eisner proposed a dating of the main types between 60 and 20 BC.54 These models were copied with some delay in Italy,55 then, with even longer delays, in the provinces, where residents more often adapted than closely adopted. In this respect, the role of soldiers was important. Recruitment in Italy, strong during the Civil War (43–31 BC) and the beginning of the Principate (until the first third of the first century AD), favoured the diffusion in the Empire of the practices of the capital. Thus, in southern Syria, there is a mixture of respect for traditions and exogenous influences.56 The same observation can be made for Gaul57 and, as will be shown below, for the Germanies and for Africa.

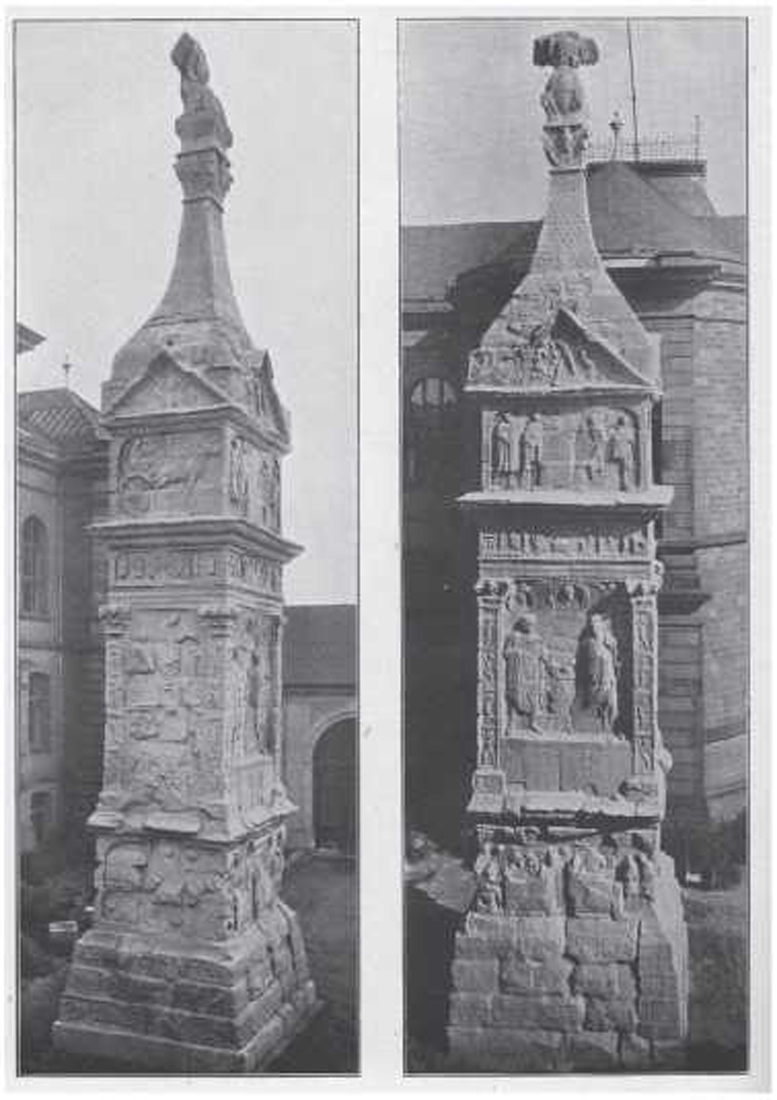

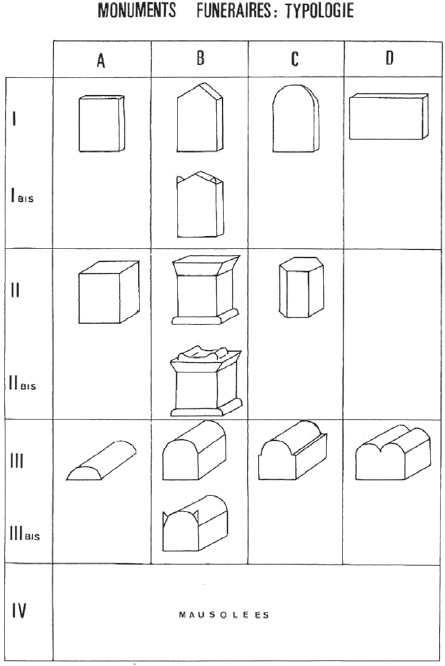

Depending on the time and the region, the monuments were constructed in diverse and varied forms. The best known are square towers, with a pointed top (as in the mausoleum of Igel in Germany, some 30 metres high and dating to the mid-third century ad; see Figure 6.2). In any case, a chamber was fitted out to receive the urn or the body. These monuments indicated the privilege of officers, at least from the rank of centurion and above, because their construction demanded sizable financial resources. In contrast, ordinary soldiers had stelae, altars and cupolas (see Figure 6.3).58

In Africa, where their number is particularly apparent, the stelae were in the form of a simple flat erect stone, sometimes topped with a semi-circular or triangular pediment, rarely accompanied with parapets and often enriched with text and (or) sculptural reliefs. They were particularly widespread in the first century ad. Funerary stelae, like the monuments discussed above, allowed the living to locate the place where the deceased had been deposited, most often in an urn, after having been cremated.

Figure 6.2: The mausoleum of Igel. (Image taken from Germania Romana 3.xxxiv, no. 1)

Figure 6.3: The types of funerary monuments found in Africa. (Drawing taken from Le Bohec, 1989, p.85)

A stele found in Haîdra (Ammaedara) depicts a legionary rider (see Figure 6.4; for other ranks of soldiers, see below). This stone is divided into two registers, with the inscription in the lower panel. Above, there is a crude, stylized face; the deceased is depicted wearing a tunic, and is shown with a prominent nose and with both eyes globular and quite large. He holds two horses, both very small, by the bridle. No attention has been paid by the sculptor to rendering the proportions correctly. This soldier, who had received a promotion, became a duplicarius, a ‘double-pay man’ in a cavalry unit. He had only been promoted for four months when he met his death, no doubt because of illness (there is no indication that he died in battle). The Pannonian Ala (wing) was in Africa, as was Legion III Augustus. The name of the second heir has been partly erased by time (see Figure 6.4):59

‘M(arcus) Licinius, M(arci) f(ilius), Gal(eria tribu), Lug(uduno), | Fidelis, milit(auit) eq(ues) in leg(ione) III | Aug(usta) ann(is) XVI, fact(us) dupl(icarius) in | ala Pann( oniorum) mens( ibus) IIII, uix( it) ann( is) XXXII. | H( ic) s( itus) e( st). Q(uintus) Iulius Atticus et T(itus) | [...]nicius Saecularis, eq(uites) | [leg(ionis)] III Aug(ustae), h(eredes) eius, posuerunt.’

‘Marcus Licinius Fidelis, son of Marcus, enrolled in the Galeria tribe, originally from Lyon, served as a cavalryman in III Legion Augustus for sixteen years. He was sent as a double-pay man to the Pannonian wing for four months. He lived thirty-two years. He is resting here. Quintus Julius Atticus and Titus [...]nicius Saecularis, cavalrymen of Legion III Augusta, his heirs, set up [this stele].’

The stelae that are catalogued chronologically below are usually dated to the second century AD and belong to members of the military who lived in Africa. These were simple blocks of stone, sometimes placed on a plinth, sometimes topped with a pediment; in rarer cases, they supported volutes. Some monuments had six faces. The urn was deposited either inside the monument, in a small prepared space, or below in the ground. Such monuments were used for rites common to all the cults of the time, especially the libations and sacrifices that preceded the funeral banquet. The officiant poured some wine on the stone and slaughtered an animal there, or burned incense, and the participants then took part in a communal meal. To represent a home, the sculptor sometimes depicted a flame, which has often been mistaken for a pine cone, a plant that has nothing to do with this context. Some current archaeologists, however, who are very cautious, do not elaborate on the nature of these sculptures and merely describe them as ‘ovoid’. In addition, these small monuments were sometimes decorated with bucranes (emaciated cow skulls), garlands of flowers, sculptures representing Eros or Victory (triumph over death), an urceus (a vase or jug) or a peg. All these symbols were meant to remind those concerned that the deceased was still alive.

Figure 6.4: The funerary monument of Marcus Licinius. (Image taken from Le Bohec, 1989, p.102, no. 23)

A very fine example of a funerary monument was found at Lambèse in Numidia: the upper part was damaged, as well as the lower left corner. It now bears, on the face, only an inscription. This deceased soldier was originally from Madaure, in the north-east of present-day Algeria. He did not serve long, and died when he was young (see Figure 6.5):60

‘D(iis) M(anibus) s(acrum). | M(arcus) Att | ius, M(arci) fi(lius), | Quir(ina tribu), Fes | tus, M(a)d(auris), miles | leg(ionis) III Aug(ustae), uix(it) ann(is) XX.’

‘Consecrated to the spirits of the dead. Marcus Attius Festus, son of Marcus, enrolled in the Quirinal tribe, originally from Madaure, soldier of Legion III Augusta, lived twenty years.’

Figure 6.5: The funerary monument of Marcus Attius. (Image taken from Le Bohec, 1989, p.90, no. 1)

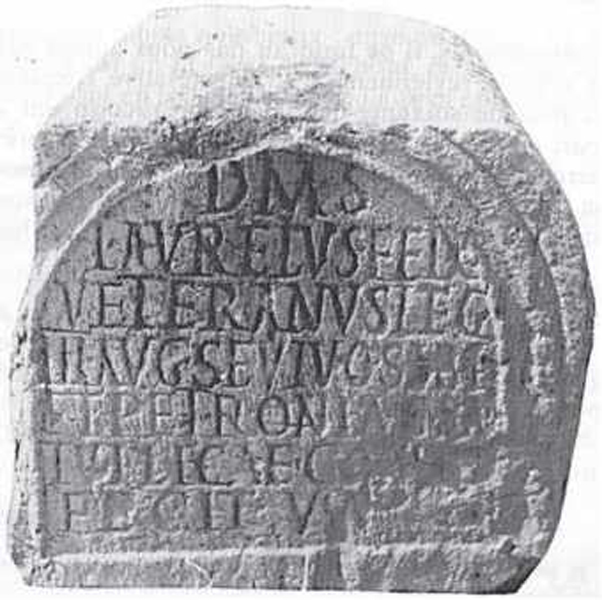

In the early third century AD, cups or boxes appeared in African and Numidian funerary iconography. They are half-cylinders placed on the edge of the monument. In more complex and infrequent cases, a half-column surmounted a rectangular base; there are also acroteria. Very rarely, the caissons were coupled. A very simple, and more classical model, was also found in Timgad. In this inscription, and others, the term veteranus referred to a former soldier, free from military obligation. He held the rite of conubium and could therefore have a legitimate wife (see Figure 6.6):61

‘D(iis) M(anibus) s(acrum). | L(ucius) Aurelius Felix, | ueteranus leg(ionis) | III Aug(ustae), se uiuo sibi | et Petronia[e S]a | ttullae, co[n(iugi)] | fecit. Vi[x(it) a(nnis) ...].’

‘Consecrated to the spirits of the dead. Lucius Aurelius Felix, veteran of Legion III Augusta, had this monument made for himself and his wife, Petronia Satulla. He lived ... years.

Figure 6.6: The funerary monument of Lucius Aurelius. (Image taken from Le Bohec, 1989, p.91, no. 3)

The image of the dead soldier

The soldier, before his death, or his heir after his death, may have wished to leave a message to the living through the iconography of his funerary marker. Historians often speak of ‘self-representation’, but it is also sometimes, and perhaps most often, the image that the living had of the dead.62 Thus an iconographic evolution had taken shape. The deceased, if he lived in his grave,63 also spent part of the year either underground in the underworld or in the heavens. The winds accompanied the deceased in his travels.64 Symbolic garlands of flowers adorned the graves65 and represented offerings. Bas-reliefs represented these asylums of peace on the funerary reliefs of civilians, but the military instead preferred rather to depict themselves. Whether the image came from his heirs or from himself, a dead soldier preferred to boast about what he had been (a soldier), than to turn towards what he had become (a dead person).66 There are four major types of representations.

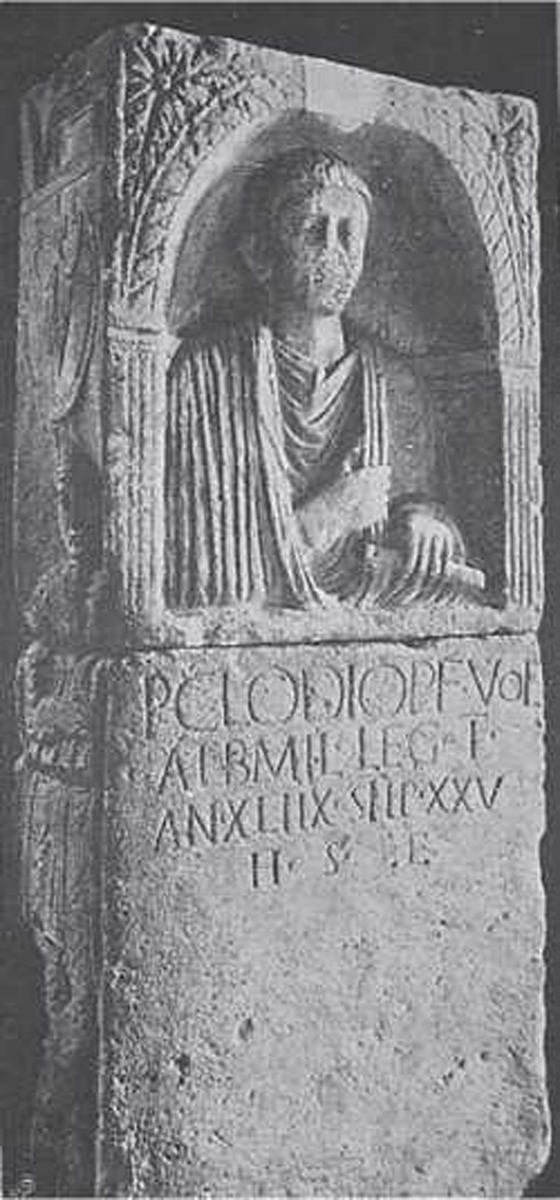

Figure 6.7: The funerary monument of Publius Clodius. (Image taken from Germania Romana 3, p.ii, no. 3)

The dead were represented as a bust, front or profile, in a niche or in relief. They are most often dressed in a toga when they are Roman citizens, which is the normal case for legionaries. A soldier – Publius Clodius – known from his funerary stele in Bonn, Germany, is depicted frontally, under an arch. He is dressed in a toga and holds a scroll, which simply means that the deceased could read and write, or perhaps he had acquired, by initiation, religious knowledge which ensured his survival in the afterlife. Clodius does not mention his cognomen, nor the name of his legion. It was Legion I Germania which was garrisoned in the city of Bonn from around AD 35–70/71.68 Originally from Liguria, this soldier was recruited aged 23. It is possible that he was a discharged veteran at the time of his death, and that he had kept, as did many of his colleagues, his title of soldier (see Figure 6.7):67

‘P(ublio) Clodio, P(ublii) f(ilio), Vol(tinia tribu), Alb(intimilio), mil(iti) leg(ionis) I. (Vixit) an(nis) XLIIX, stip(endiorum) XXV. H(ic) s(itus) e(st).’

‘To Publius Clodius, son of Publius, enrolled in the Voltinia tribe, originally from Ventimiglia, a soldier of Legion I. He lived forty-eight years, and he served twenty-five years. He rests here.’

Other individuals were depicted in full on their monuments (see Figures 6.8–9) and three different types of representations were common. In one, the deceased simply faces the viewer. He is in this case dressed either in civilian clothes or as a soldier. In the latter case, it is possible to study his armament, which is particularly interesting for auxiliaries, who could be equipped with shields and armour, and who were provided with a bow, a spear or a sword. Alternatively, the dead are depicted sacrificing at an altar. In this case, they are usually in civilian clothes.

One legionary, Gaius Valerius Crispus, appears in such a representation. He is known from a stele from Wiesbaden, Germany.69 In the depiction he stands under an arch, and is positioned face-on to the viewer. He wears a complete set of armour, a plumed helmet (the plume is often omitted in such depictions), a cuirass whose type is difficult to identify under the garment that covers it, and a tiled shield that is about 60cm high (the umbo, the half-ball placed in the centre of the shield, is apparent). For the offensive elements of his equipment, he wears a relatively long and very sharp sword on the right side, and holds in his hand the famous pilum, a thin javelin. The inscription provides further information about him; the brother referred to was perhaps a brother by blood or a brother in arms:70

‘C(aius) Val(erius), C(aii) f(ilius), Berta, Menenia, Crispus, mil(es) leg(ionis) VIII Aug(ustae), an(nis) XL, stip(endiorum) XXI. F(rater) f(aciendum) c(urauit).’

‘Gaius Valerius Crispus, son of Gaius, originally from Berta [in Macedonia], enrolled in the Menenia tribe, [rests here]. Soldier of Legion VIII Augusta. He lived forty years and he served for twenty-one years. His brother had this monument made.’

Another legionary, Quintus Luccius Faustus, was buried at Mainz amongst other military graves. The particularity of his grave lies in the fact that he was, at the moment of death, a signifer, bearer of the signum (the standard of the maniple and the cohort).71 He too, on his stele, is on foot and he stands facing the spectator. On his left there is a little laughing head, the significance of which remains to be established. Quintus is bare headed: he is wearing armour, has a pilum, and his left hand carries his shield, which curves behind him. He carries, on his right side, a sword similar to that of the previous individual discussed. In the right hand he holds an upright signum, a long spear-shaped pole, on which are fixed six disks which are decorations for combat awarded to his unit. The inscription does not mention his rank of signifer, because the relief is sufficient.72 This soldier was born in Pollenzo, Liguria. Legion XIV Gemina stayed in Mainz from AD 13–43 and from AD 71–92:73

‘Q(uintus) Luccius, | Q(uinti) f(ilius), Pollia, | Faustus, Pol(l)e | ntia, mil(es) leg(ionis) | XIIII Gem(inae) Mar(tiae) | Vic(tricis), an(norum) XXXV, | stip(endiorum) XVII, h(ic) s(itus) e(st). | Heredes f(aciendum) c(urauerunt).’

‘Quintus Luccius Faustus, son of Quintus, enrolled in the Pollia tribe, originally from Pollentia, a soldier of Legion XIV Gemina Martia Victrix, lived for thirty-five years, and served seventeen years. He is resting here. His heirs took care to make [this monument].’

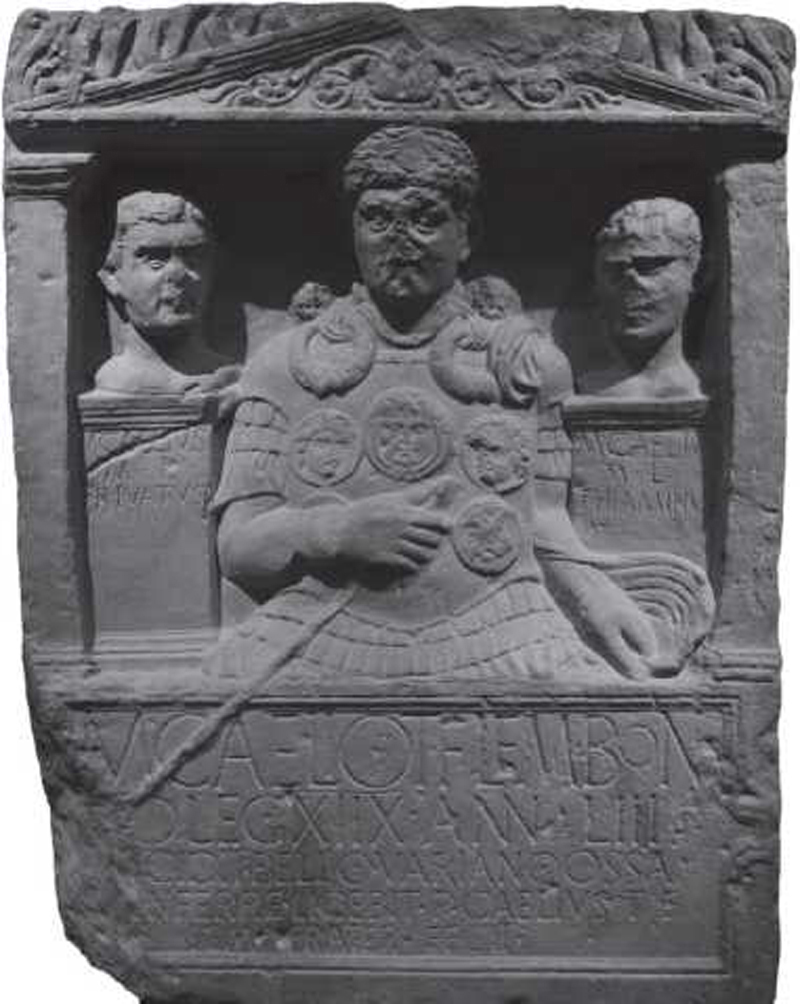

A stage higher in the military hierarchy is reached with an eagle-bearer, an aquilifer. He is known from a stele, also found in Mainz. The soldier, the aquilifer Gnaeus Musius, as always shown from the front, is framed by two columns that support a pediment: he is in a temple as the dead are close to the gods, but not deified. Yet he will nevertheless join the cohort of dii Manes. Bare-headed, he wears a cuirass covered with nine disks, which are decorations he has won in combat. His left hand is leaning on his shield, which rests on the ground. In the right hand, he holds a shaft on the top of which is an eagle, with wings spread, standing on Jupiter’s thunderbolts. This eagle standard, like the signa, was sacred and it was housed in the sanctuary which was in the centre of the camp. This Italian, a native of Veleia located 18km from Plaisance, died young and was probably buried by his blood brother rather than by a brother in arms (they carry the same name). (see Figure 6.8; the funerary inscription, underneath the relief, is not shown.)74

‘Cn(aeus) Musius, T(iti) f(ilius), | Gal(eria tribu), Veleias, an(nis) | XXXII, stip(endiorum) XV, | aquilif(er) leg(ionis) XIIII Gem(inae). | M(arcus) Musius, (centurio), frater, posuit.’

‘Gnaeus Musius, son of Titus, part of the Galeria tribe, from Veleia, lived thirty-two years and served fifteen years. He was an eagle-bearer of Legion XIV Gemina. The centurion Marcus Musius, his brother, set up [this monument].’

In another type of sculptural relief, common amongst the military, the deceased is presented reclining on a dining couch, taking part in a banquet. Before him is positioned a tripod upon which are placed food and drink. He is served by a young boy and sometimes by his wife. This theme is typically Greek, and it was an honour during the Hellenistic period and under the Roman Empire (Egypt included) to be depicted in this way.75 From Greece, the iconography made its way to Germania, either through the agency of travellers who had taken the Danube–Rhine route, or from soldiers who served in Macedonia at the beginning of the Empire and who were then sent to other garrisons. Then it was adopted, not only by soldiers, but also by civilians. Such monuments are found in Bonn,76 Cologne,77 Trier,78 Wiesbaden,79 Karlsruhe80 and Obernburg.81 A civilian from Pettau, modern Ptuj in Slovenia (Poetouio in antiquity), received a monument that evokes the one that was found at Ighil Oumsed (Mauretania Caesarea, see below). A reclining figure was placed at the top, and the banquet below.82 Legionaries from Germany, who contributed to the conquest of Britain in AD 43, brought this theme with them to that province.

Figure 6.8: The funerary monument of the aquilifer Cnaeus Musius. (Courtesy of Alamy)

Similar depictions are found on monuments in the Chester (Deva) camp of Legion XX Valeria, for soldiers83 and civilians alike.84 This legion left Dalmatia for Germany in AD 9 (it replaced one of the three legions destroyed in the disaster of the Teutoburg Forest). It was garrisoned in Cologne from AD 9–35 and then in Neuβ from AD 35–43. It then participated in the invasion of Britain, where it remained.85 Note that in all British cases except one,86 the table has three feet. This iconography shows the religious feeling of the deceased, and the concept of the hereafter where he would banquet for eternity, without tiring himself.

A relief of Chester illustrates this iconographic type. The deceased is more seated than reclining, which is rather rare. He holds in his left hand a scroll which, as has been noted, may be an affirmation of some education or a religious text opening the doors into a better beyond. Near him is a small person, perhaps his wife or a servant. In front of him is positioned the small three-legged table that holds food and drink. This soldier was Thracian; he came from present-day Bulgaria. He is unlikely to have died at the age of just 40, because it is hard to imagine that he was recruited at 14. The ancients sometimes used rounded numbers in giving someone’s age. Although the inscription is in somewhat rough Latin, it can be readily understood:87

‘D(iis) M(anibus). | C(a)ecilius Donatus, B | essus na | tione, mili | tauit ann | os XXVI, uix | it annos XXXX.’

(‘To the spirits of the dead. Caecilius Donatus, from the Bessus nation, served twenty-six years, and lived forty years.’)

Funeral banquet imagery for the deceased also reached Africa, and is found on a soldier’s grave from Ighil Oumsed in Algeria.88 Cavalrymen are very numerous in military representations. They were the superiors of the infantrymen: a cavalry decurion outranked a cohort centurion and was better paid.

A very interesting example of the funeral monument with a charging rider was found in Germany, from where its iconography spread to Britain and Africa. In general, the deceased is shown in the process of being about to dispatch a fallen enemy warrior. In an original pose in this particular relief, the dead cavalryman, on the point of becoming a divine hero (as he will die shortly after), is depicted in a small temple. He holds a short javelin in his hand, which he throws at his fallen enemy, and carries a large shield across his back; the harness of the horse is reproduced with precision. The defeated opponent also has a large sword, which he wears on the right side. He is lying on his back and attempts to protect himself with his large shield, on which the umbo can be seen. This sculpture is not accompanied by an inscribed text, which is curious, and it is possible that the letters had been painted on rather than inscribed (compare Figure 3.4).89

Other cavalry representations, but more rarely, depict non-violent themes. They show a ‘rider on the right’ (i.e., moving to the right of the viewer), advancing calmly. Such monuments were found in Karlsruhe (Germany) and Chalon-sur-Saône (Gaul),90 as well as Ighil Oumsed (see above). When a rider had been rewarded for his merits through double pay, he also received two horses, and was thus represented between his two mounts (see Figure 6.4).

Other, more diverse subjects and objects, such as varying weapons or decorations, may also have been sculpted, without it being known why in all cases. A representation with family is rare. Indeed, the Roman dead fell into two categories. Some wanted to be totally alone in their eternal home, and these ‘solitaries’ represented an overwhelming majority of the population, more than 80 per cent. Others wanted to be accompanied by their wife or children. The rarest case attested, however, was one in which the whole family, including the wife, children and freedmen, benefitted from a collective burial.

Another special category is that of the cenotaphs, of which there were few in number. Most famous of these is one discovered in Germania, in Xanten (it is currently housed in the Bonn Museum, see Figure 6.9). This rectangular stele is divided into three registers. At the top is a triangular pediment. Below are three individuals, one large and two small. The relief represents a centurion who died in the disaster of Varus in AD 9; the imagery is cut-off at the height of his abdomen. The deceased wears a cuirass covered with decorations, two bracelets (armillae) and at least four medals. In his right hand he holds his command stick, the vitis (‘vine stock’). He is flanked, on the left and the right, by two smaller heads, which are cut just below the level of the neck. They represent two freedmen who had followed the deceased to Germany and who died with him; below their busts, inscriptions indicate their identity.91 Ossa [i]nferre licebit in the inscription has been variously interpreted – here the translation which seems to be the most acceptable is given (‘May it be possible to bury his bones’):

Figure 6.9: The funerary monument of Marcus Caelius. (Courtesy of Alamy)

‘ M(arco) Caelio, M(arci) f(ilio), Lem(onia tribu), Bon(onia), | (centurioni) leg(ionis) XIIX, ann(is) LIII (semissis). | [Ce]cidit bello Variano. Ossa | [i]nferre licebit. P(ublius) Caelius, T(iti) f(ilius), | Lem(onia tribu), frater, fecit. || M(arcus) Caelius, | M(arci) L(ibertus), | Privatus. || M(arcus) Caelius, | M(arci) L(ibertus), | Thiaminus

‘To Marcus Caelius, son of Marcus, enrolled in the Lemonia tribe, originally from Bologna. Centurion of Legion XVIII, he fell in the war of Varus at the age of fifty-three and a half. May it be possible to bury his bones. Publius Caelius, son of Titus, enrolled in the Lemonia tribe, his brother, had this monument made. [Portrait of] Marcus Caelius Privatus, freedman of Marcus. [Portrait of] Marcus Caelius Thiaminus, freedman of Marcus.’

It is likely that several reliefs included painted details. On the stele of Ighil Oumsed, mentioned above, the harness of the horse is very incomplete, meaning that in its preserved state, the rider could not have led his horse. Moreover, it has no saddle or weapons, which is strange for a soldier shown in the exercise of his function. Relevant painted details on such reliefs have clearly weathered and disappeared.

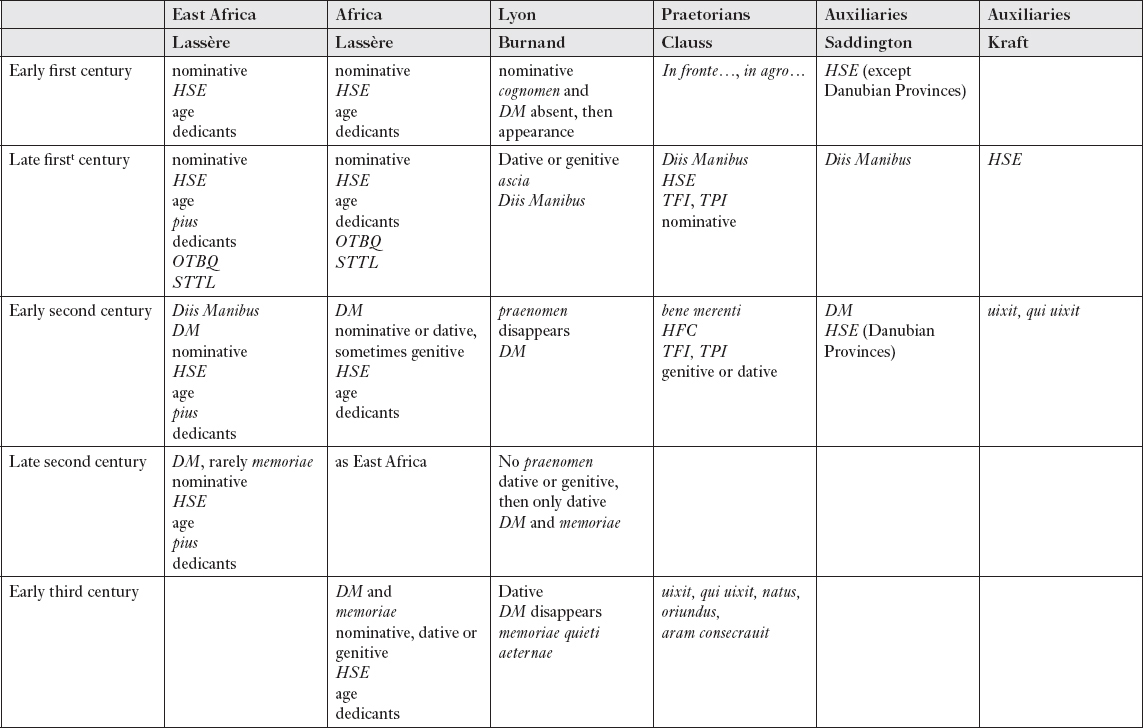

Figure 6.10: Common motifs in funerary inscriptions for different regions and different military functions and positions.

The word of the dead soldier

Part of the tombs bore sculptures, while another part carried engraved texts.92 Of course, the most detailed are those with an image accompanied by an inscription. Epigraphy greatly complements the iconography of the funerary monuments, both of which more or less developed according to the times, region and rank of the soldier. As is shown below, the different styles of inscription sometimes overlap, and it is difficult to find texts in only one style; there is nevertheless value in cross-examining the information which they provide, given that each complements the other. A difficulty arises in regard to the monuments, in that their epitaphs are almost never accurately dated. Yet some researchers have studied inscriptions which are the exceptions, because the time of writing is known; they have found that most homogeneous forms correspond to well-defined periods, and they are thus able to establish a chronology of texts taking into account their different elements.93

Abbreviations

DM: Diis Manibus, ‘To the the spirits of the dead’

HFC: H(eres, -des) f(aciendum) c(urauit – erunt), ‘The heir (or heirs) has (have) taken care to erect (this monument)’

HSE:H(ic) s(itus) e(st), ‘He rests here’.

OTBQ: O(ssa) t(ua) b(ene) q(uiescant), ‘May your bones find good rest’

STTL: S(it) t(ibi) t(erra) l(euis), ‘May the earth rest lightly [upon him]’

TFI: T(itulum) f(ieri) i(ussit), ‘He ordered to have the inscription engraved’

TPI: T(itulum) p(oni) i(ussit), ‘He ordered to have the inscription set up’

Just as a soldier’s relief was intended to perpetuate the memory of the dead through the iconography of the memorial, so too the inscription through its text informed contemporaries of what was of value to him. Four main elements extolled the value of virtus (‘virtue’, ‘manly excellence’). First, the soldier brought posthumous fame to the unit in which he had served, even if he was not among its most prestigious members. Secondly, it boasted of his rank, even if that had been modest. Thirdly, he did not always neglect to mention his commanding centurion. Above all, finally, the decorations he had achieved during his service are listed.

It is largely not pertinent to emphasize here certain elements common to the funerary memorials of both civilians and the military alike. Yet one feature is significant: the invocation on the graves for protection by the spirits of the dead (dii Manibus). In addition, during the fighting, the Manes were believed to accompany the soldier, who was also protected by the gods of Rome. In addition, one often finds the expressed desire, STTL (S(it) t(ibi) t(erra) l(euis) – ‘May the earth rest lightly [upon him]’) – and other phrases such as HSE (Hic situs est – ‘He rests here’) in the funerary inscriptions.

Naturally, the soldier wanted to have his onomastics (his names) preserved after his death. His name, of course, was very important: when reading the inscription, and pronouncing the soldier’s name, each passer-by gave a little life to the deceased. In addition, for the modern historian, it helps to date the inscription, and it allows the placing of the deceased in a particular social level.94 A free man but not a citizen (he was said to be a peregrinus), the auxiliary was entitled to only one name. As a Roman citizen, a legionary soldier bore the tria nomina: praenomen-nomen-cognomen, such as, for example, Caius Iulius Caesar. To ensure the recognition of his status as an individual, the deceased soldier was identified in an inscription only by the praenomen and nomen at the beginning of the Empire, such as Marcus Caelius and Publius Caelius in the examples given above. In such cases, the cognomen is omitted. From the beginning of the second century, it was the praenomen that tended to be omitted, and the nomen-cognomen couplet represented the norm.

Military elements accompanied the onomastics: the soldier wanted his rank to be remembered after his death. Some very simple texts are inspired by those engraved for civilians. Only one difference appears, the mention of the soldier’s status, as can be seen in this inscription from Lambèse:95

‘D(iis) M(anibus). | C(aio) Iulio Fortunato, armo | um (custodi), q(ui) uix(it) an(nis) XXXVII. | Sex(tus) Pompeius Seueri | anus, uet(eranus), in suo gene | ro carissimo, s(ua)p(ecunia) f(ecit). | H(ic) s(itus) e(st). O(ssa) t(ua) b(ene) q(uiescant).’

(‘To the spirits of the dead. To Caius Julius Fortunatus, weapons keeper, who lived thirty-seven years. Sextus Pompeius Severianus, a veteran, commissioned this monument at his expense for his very dear son-in-law. He is resting here. May your bones find quiet rest.’)

This inscription contains only two terms connecting it to the army: the titles of weapons keeper and veteran. The place where this monument was discovered proves that the soldier served in Africa, in Legion III Augusta; the rest of the text, however, could easily have suited any civilian figure. A soldier may have also wanted the unit in which he served to be known after his death. The normal rule is that the unit is mentioned, in addition to his rank (or function) within the unit. There was a sense of pride in the name, and also a kind of patriotism and esprit de corps. Naming the centuria to which he belonged was also considered to be a means of honouring him after death, and soldiers were sometimes described with the formula ‘of the x century of...’. This can be seen in an example of such a text from Rome; this soldier came from Urbinum (modern Urbino), a city in Umbria:96

‘Sex(tus) | Vaternius, | Sex(ti) f(ilius), Ste(llatina tribu), | Certus, Vruino Mataur( ensi), | mil( es) coh( ortis) XII urb( anae), | (centuria) Metili, | milit( auit) ann( is)’

(‘Sextus Vaternius Certus, son of Sextus, enrolled in the Stellatina tribe, originally from Urbino on the Mataurus, soldier of the XII urban cohort, from the century of Metilius, served ... years’

With respect to rank, several epigraphic possibilities were available. The inscription may have stated that the deceased was simply a ‘soldier’ (miles): a word that covers all military connotations, from recruit to emperor (as per Trajan in the Panegyric of Pliny). Sailors also claimed to be milites and not nautae, that is combatants, not rowers. Other soldiers were given an administrative or tactical responsibility, which meant they were exempt from other duties. They mention this exemption (immunis) and the duty which was assigned to them (signifer or actarius, aquilifer or notarius, or such like). Strictly military roles were also distinguished (infantry, cavalry, artillery, signaller, intelligence and trainer), as were services (logistics, engineering, workshops and priesthoods), administrative functions (many), justice and policing. Above these, there was a whole hierarchy of ranks as well, going from the centurion to the tribune, then to the legate and the emperor, the supreme commander of the armies.

For those with musical functions in the Roman Army, an example can be seen in the monument to a horn player. The stele is appropriately decorated with a sculpture of a soldier playing this instrument:97

‘D(iis) M(anibus). M(arcus) Antonius, | M(arci) f(ilius), Ianuarius, | domo Laudicia | ex Suria, cornice(n) | ex coh(orte) VII pr(aetoria), (centuria) Apri, | uix(it) ann(is) XXXII, mil(itauit) | [ann(is) ...]’

(‘To the spirits of the dead. Marcus Antonius Januarius, son of Marcus, from Laodicea, Syria, was a horn player in the VII Praetorian cohort, in the centuria of Aper. He lived thirty-two years, and he served ... years.’)

Another example is provided by a monument to a trumpet player, a tubicen:98

‘D(iis) M(anibus) s(acrum). | C(aius) Iulius Victo[r], | tub(icen) leg(ionis) III Aug(ustae), u(ixit) a(nnis) XXXIII. | Auf(idia) Dona | ta, her(es), mate(r), | fecit.’

(‘Consecrated to the spirits of the dead. Gaius Julius Victor, trumpeter of Legion III Augusta, lived thirty-three years. Aufidia Donata, his heir, his mother, had this monument made.’)

For those holding administrative positions, the records of two frumentarii, who are mentioned in a single inscription, serve as an example:99

‘D(iis) M(anibus). | M(arcus) Taricius Atto, fr(umentarius) | leg(ionis) I Adiutrices (sic), Car | tino Grato, fr(umentario) | leg(ionis) X Gem(inae), colle(gae) | b(ene) m( erenti), f( ecit).’

(‘To the spirits of the dead. Marcus Taricius Atto, frumentarius of Legion I Adiutrix, made (this monument) for Cartinius Gratus, frumentarius of Legion X Gemina, his colleague, who deserved it.’)

Both the legions referred to in this inscription belonged to the army of Upper Pannonia. In the early days of the Roman Army, the frumentarii were soldiers charged with finding wheat (i.e., they were foragers). Little by little, as their mission took them away from their units, they also became scouts and couriers. Under the Principate, they were mainly employed for the exchange of letters between the provincial governors and the emperor. In Rome, they were housed in a special camp, the castra peregrina.

Yet it was the unit that mattered most. As an African inscription says: Tanta legio III Augusta!’ (‘The great Legion III Augusta!’).100 Pride increased with the prestige of the unit. Sailors were placed at the bottom of the ladder, the auxiliaries were above them, the legionaries were positioned higher still, and the garrison of Rome – especially the urbaniciani (city cohorts) and praetorians – were above all these personnel. Funerary monuments have been found for many of these positions, and examples are given below.

Praetorian:101

‘C(aius) Fabius, | C(aii) f(ilius), Ser(gia tribu), | Crispus, | Carthag(ine Noua), | specul(ator) | coh(ortis) VI pr(aetoriae), | (centuria) Flegeri, | mil(itauit) an(nis) XIII, | uix(it) an(nis) XXII. | Heres, | ex uolunt(ate), p(osuit).’

‘Gaius Fabius Crispus, son of Gaius, enrolled in the Sergia tribe, originally from New Carthage, scout of the Sixth Praetorian cohort, from the centuria of Flegerus, served for thirteen years, and lived for twenty-two years. His heir had this monument erected according to his will.’

It was thought that the name Flegerus had been misread (the stone has long since disappeared), and there is an error with one of the two figures XIII and XXII: where the deceased lived XXXII years, or served III years, as recruiters never took 9-year-olds into the military. The city is New Carthage (modern Cartagena), and not Carthage, because the Sergia tribe was assigned to this Spanish city, the African being in the Arnensis. The uoluntas was the last will and testament.

Legionary:102

‘ D( iis) M( anibus) s( acrum). | C( aius) Valerius | Secundus, | mil( es) leg( ionis) III | Aug(ustae), u(ixit) a(nnis) XL. | Iulius Rusti |cus, | heres, fecit.’

(‘Consecrated to the spirits of the dead. Gaius Valerius Secundus, a soldier of Legion III Augusta, lived forty years. Julius Rusticus, his heir, had this monument made.’)

It is a comrade-in-arms who buried the deceased, which does not prove the homosexuality of both, contrary to what some scholars have suggested.

Cavalryman:103

‘Di(i)s Manibus. Flauinus, | eq(ues) alae Petr(ianae), signifer | tur(mae) Candidi, an( nis) XXV, | stip( endiorum) VII. H( ic) s(itus est).’

(‘To the spirits of the dead. Flavinus, a cavalryman of the Petrian Ala (wing), bearer of the signum (standard) in the squadron of Candidus, lived twenty-five years, and served seven years. He rests here.’)

A cavalry Ala was divided into fourteen to sixteen squadrons (at least 360 men), and twenty-four when it was on campaign (with about double the number of men). Each squadron was commanded by a decurion, a junior officer. The deceased in this inscription was not a Roman citizen (note the single name), and was probably a foreigner. Note that in the following inscription, the Vangiones were a people of Germany, whose capital corresponded to the present-day Worms.

Auxiliary infantryman:104

‘D(iis) M(anibus) s(acrum). Decimus Iuliu/s, Q(uinti) f(ilius), Candidus, c(o)ho(rtis) | p(rimae) Vangionum, a(nnorum) XXXX.’

‘Consecrated to the spirits of the dead. Decimus Julius Candidus, son of Quintus, of the First cohort of Vangiones, lived forty years.’

Marine:105

‘M(arcus) Epidi|us Qua | ratm, miles | ex classe | Misenens(i), | (centuria) Cn(eii) Valeri(i) | Prisci, | milit(auit) an(nis) III, | uix(it) an(nis) XXVI. | Hic situs est.’

‘Marcus Epidius Quadratus, soldier of the fleet of Misenum, of the century of Cneius Valerius Priscus, served three years and has lived twenty-six.’

This sailor, who died young, was present as a ‘soldier’, and does not mention the name of the boat on which he served, but he designates the commander of his ship, who had the rank of centurion, like all the officers who fulfilled this function.

The soldier sometimes insisted that his attachment to the emperor, the supreme commander of the military, be known after his death. Indeed, from the time of Septimius Severus, units were honoured by nicknames from the imperial onomastics. These epithets were at first significant honours, but then they multiplied and became commonplace. They serve to date an inscription by reference to this or that emperor. A legion could be seueriana (Septimius Severus), antoniniana (Caracalla), seueriana alexandriana (Severus Alexander), and so forth. It also happened that it was honoured by an added adjective touting its merits, such as pia (respectful of its duties) or fidelis (loyal to the emperor; ‘infidelis’,‘unfaithful’, often being the name given to military units in civil wars). There is a very rich textual corpus of examples for such epithets, such as the funerary inscription for Julius Maximus:106

‘Iulius Maxim[us], | mil(es) leg(ionis) III Aug(ustae) | Antoni[ni]an(a)e, s(e) u(iuo), cupula(m) f(ecit) s(uo) s(umptu). | An(n)oru(m) circiter | LIV.’

‘Julius Maximus, a soldier of Legion III Augusta Antoniniana Legion, had his tomb made during his lifetime and at his expense. He lived about fifty-four years.’

Here, the nickname ‘Antonine’ refers to Caracalla, who claimed to be a descendant of Marcus Aurelius, who belonged to the Antonine dynasty. This tomb is the type of monument described earlier, with a half-column placed on the base, characteristic of Africa in the third century.

The duration of the soldier’s service could also be mentioned in three ways: aerum, stipendiorum and militauit. Curiously, in the first two cases, it is the number of years of wages which was mentioned by two quasi-synonyms: ‘I received so many years of wages.’ In the latter case, the verb is followed by the number of years of service: ‘I have been a soldier for so many years.’ In general, this reference was supplemented by the age at death. Entries show that soldiers were recruited between the ages of 18 and 21. They also show that the life expectancy for a legionary did not exceed 47 years on average.

Use of aerum:107

‘D(iis) M(anibus) | L(ucii) Pollenti(i) | Dextri, L(ucii) fil(ii), domo Saueria (sic), | mil(itis) legion(is) | I Adiutri(cis), | (centuria) Alli(i) Mar[i] ni, anno(rum) XXIII, aerum | V. H(ic) s(itus) | e(st). Her(es), ex | testamen(to), fac(iendum) cur(auit), Q(uintus) Val(erius) Rufus.’

‘To the spirits of the dead. For Lucius Pollentius Dexter, son of Lucius, native of Savaria, soldier of Legion I Adiutrix, of the centuria of Allius Marinus. He lived twenty-three years and served five years. He is resting here. His heir, Quintus Valerius Rufus, took care to have this (monument) made under the will of the deceased.’

The soldier was from Savaria in Upper Pannonia, today Szombathely in western Hungary, and Legion I Adiutrix encamped in this province under Domitian, in Dacia in the early second century, then returned to Pannonia. As we have already noted, if a man ensures the burial of another man, that does not prove homosexuality. Epigraphists have debated whether this soldier’s homeland was Carrhae in Syria or, more likely, Carreum Potentia (Chieri) in Italy.

Use of militauit:108

‘L(ucius)Mettius,M(arci)f(ilius), Poll(ia tribu), | Martialis, Carr(eo), | specul(ator), mil(itauit) an(nis) X, uix(it) an(nis) XXX.’

‘Lucius Mettius Martialis, son of Marcus, enrolled in the Pollia tribe, originally from Carreum, served as scout for ten years. He lived thirty years.’

There are still other features of the funerary inscriptions for soldiers. A soldier was most anxious that his excellence be known after his death. Simple milites and officers loved decorations, or dona militaria, and parents of the deceased never failed to mention those who had received them. Rank-and-file soldiers were awarded necklaces, bracelets (armillae) and so-called phalerae medals, always for their courage. Officers were honoured with wreaths, spears without iron (that is to say in bronze, gold or silver) and banners called vexilla, which were awarded to them simply for their participation in a campaign. An example of an inscription from Africa, for a cavalryman, outlines exceptional and rewarded service:109

‘Militauit annis XXXV. | C(aius) Titurnius Quartio, eques legionis III | Gallicae, cui imp(eratores) Aug(usti), bello Phartico (sic), Seleucia | (et) Babylonia, torquem et armillas donauerun[t], | uotum suum reddidit.’

‘He served thirty-five years. Gaius Titurnius Quartio, a cavalryman of Legion III Gallica, fulfilled his wish. The emperors decorated him, during the Parthian war in Seleucia and Babylon, giving him a necklace and bracelets.’

This inscription was engraved on the pediment of a shrine. Quartio had received as decorations a necklace (torque) and two bracelets (armillae, or ‘arm bands’) that were carved beside the dedication. In this case, the text and the image complement each other perfectly. Seleucia was on the right bank of the Tigris, 22 miles south of what is now Baghdad and 60 miles north of Babylon. The two emperors referred to are either Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, or Septimius Severus and Caracalla. Legion III Gallica had always been part of the Syrian Roman Army; it is not known how or why this soldier ended his days in Africa (modern Tunisia).

Inscriptions may state who was responsible for the burial. Sometimes, especially at the beginning of the Principate, this task fell to a brother in arms, as was seen earlier: although two men having the same foreign name did not mean they had the same parentage; they are not brothers by blood, but by service. Some modern authors see in this kind of practice the proof that homosexuality was very widespread among legionaries, especially at this time when marriage was prohibited. Such an argument does not seem very convincing because this type of behaviour was not viewed positively within the Roman Army, despite what Veyne has suggested. In any case, soldiers were soon allowed to form relationships with women who gave them children. Although these unions were not legal, these people formed families and gave themselves family titles by courtesy: the soldier was the father of the children and the husband of the woman, who was then wife for one and mother for the others.

Finally, other people normally referred to as ‘heirs’ could fulfil this mission. In an inscription from Africa, which illustrates this point, it is the heir who has erected the monument:110

‘M(arcus) Sempronius, | M(arci) f(ilius), Gale(ria tribu), Lugud(uno), | mil(es) leg(ionis) III Aug(ustae), (centuria) Ex(),| uix(it) an(nis) XXV, | mil(itauit) an(nis) V. | H(ic) s(itus) est. | T(itus) Baronius, (centuria) Sallu | [stii Sallu/stii, her] es, posuit.’

‘Marcus Sempronius, son of Marcus, of the Galeria tribe, native of Lugdunum, soldier of Legion III Augusta, in the centuria of Ex(...), lived twenty-five years and served five years. He is resting here. Titus Baronius, of the centuria of Sallustus, his heir, set up (this monument).’

Conclusion

Law and religion, archaeology and epigraphy, as well as written texts, all show how soldiers and their parents and heirs conducted the worship of the dead. As expected, the soldiers practised the same funeral rites as civilians. It can be seen, however, both in the necropoleis and in the monuments that were erected in them, that differences existed between civilian and military funerary rites, customs, and practices. Funerary monuments and stelae, by their iconography and their inscriptions, make it possible to come to a better understanding of the soldier’s profession. Inscriptions clearly indicate how the military attached particular importance to their rank, their unity and their decorations. The iconography and the inscriptions of soldiers’ funerary monuments from across the Empire provide evidence for standard concerns on the part of soldiers and their friends, family or heirs, that the soldiers not be forgotten. Especially, in particular, these monuments, reliefs and inscriptions reveal that soldiers and those they left behind wanted their military service to be memorialized and remembered.

Notes

1. Note the plural in the title of Beard et al. (1998); see also: Le Bohec (2016).

2. Stefan (2005), pp.437–38, 562–63, 703.

3. Grimal (1999), p.275.

4. Cumont (1942), pp.253–350.

5. Cumont (1942), p.64.

6. Lendon (2005).

7. Cumont (1942), pp. 13–16.

8. Cumont (1949), pp.142–56, 259–74.

9. Gordon (2009), pp.379–450. See now Stohl in this volume.

10. Rankov (2015), pp.194–95.

11. Acts 10.

12. Le Bohec (2006), p.185.

13. Perea Yébenes (2002).

14. Tert. Cor. Mil. 1.1–2; Le Bohec (1992), pp.6–18.

15. A thorough investigation remains to be done.

16. From Visscher (1963).

17. Tll 3.1411.

18. Strabo 16.4.10.

19. Tert. Anim. 51.

20. Cypr. Ep. 80.1

21. Optat. 6.7

22. August. Ep. 22.6

23. ICUR 2.4535, 4.10404, 4.12494, 8.22408.

24. ILCV 2000.

25. ILCV 3681a.

26. ILCV 2171.

27. CIL 8.7543.

28. CGL 5.430.22.

29. Cat. 59.2.

30. Le Bohec (2015).

31. Toynbee (1982), pp.91–94.

32. Toynbee (1982), pp.94–100.

33. See, however, Peretz (2005).

34. CIL 3.5218 (3.11691), from Celeia.

35. AE (1909), p.144: Dacisca.

36. Reuter (2005); Perea Yébenes (2009); Bertolazzi (2015).

37. Susini (1959–60).

38. Dio, 56.22; Tac. Ann. 1.62.3.

39. Tac. Ann. 1.62; Clementoni (1990), pp.197–206.

40. Asskamp & Kühlborn (1986).

41. Witteyer (1997), pp.63–76.

42. Le Bohec (1989), pp.107–110.

43. Moretti & Tardy (2006).

44. Toynbee (1982), pp.61–64.

45. Cumont (1949), pp.29–54; Grimal (1999), p.275.

46. Grimal (1999), p.275. Rosaria are not to be confused with rosalia ‘signorum’, standard celebrations, on 10 & 31 May – Groslambert (2009).

47. De Visscher (1963), pp.65–82.

48. De Visscher (1963), pp.103–06.

49. De Visscher (1963), pp.101–02.

50. De Visscher (1963), pp.112–23.

51. De Visscher (1963), pp.93–127.

52. De Visscher (1963).

53. Boschung (1987).

54. Eisner (1986).

55. Von Hesberg (2006); Sauron (2006).

56. Sartre-Fauriat (2006).

57. Sauron (2006).

58. Le Bohec (1989), pp.83–88.

59. EA (1969–70), p.661; Le Bohec (1989), p.102, fig. 23.

60. CIL 8.3043 (3.18163); Le Bohec (1989), p.90, fig. 4, no. 1.

61. BCTH (1946–49), p.234, no. 8; Le Bohec (1989), p.91, fig. 5, no. 3.

62. Le Bohec (1989), pp.92–93.

63. Cumont (1949), pp.55–58.

64. Cumont (1942), pp.35–77; Cumont (1949), pp.109–23, 142–84.

65. Cumont (1942); Cumont (1949).

66. Rinaldi Tufi (1988); Da Costa (1995).

67. CIL 13.8056; Germania Romana, 3.2, no. 3.

68. CIL 13.6898; Ritterling (1925), pp.1376–80.

69. Fischer (2012), p.163.

70. CIL 13.7574.

71. Von Domaszewski (1972), p.35.

72. CIL 13.6898.

73. Ritterling (1925), pp.1727–47; Franke, in Le Bohec & Wolff (eds) (2000), pp.191–202.

74. CIL 13.6901; Fischer (2012), p.231.

75. Dentzer (1982).

76. Germania Romana 3.10, no. 4 (civilian), and 11, 2 (CIL 13.8311: wing rider).

77. Germania Romana 3.11.3 (CIL 13.8283; Doppelfeld (1967), no. 140 and pl. 46: legionary veteran).

78. Germania Romana 3.11, no. 1 (CIL 13.8670: wing rider).

79. Germania Romana 3.11, no. 4 (CIL 13.7586: cohort soldier).

80. Germania Romana 3.10, no. 2 (civilian).

81. Germania Romana 3.12, no. 2 (CIL 13.6626).

82. Germania Romana 3.26, no. 2.

83. RIB 522 and 523.

84. RIB 558, 563 and 566;568: rank unknown.

85. Ritterling (1925), pp.1769–81; Keppie, in Le Bohec & Wolff (eds) (2000), pp.25–28.

86. RIB 522.

87. RIB 523.

88. Laporte (2013).

89. See Fischer (2012), p.324.

90. CIL 13.2613.

91. CIL 13.8648.

92. For the latter: Reuter (2005); Perea Yébenes (2009); Bertolazzi (2015).

93. Le Bohec (1989), p.64; updated with Burnand (1992), pp.21–27.

94. Le Bohec (2005).

95. CIL 13.2902.

96. AE (2012), p.252.

97. CIL 6.2627, Rome.

98. CIL 8.2926, Lambèse.

99. CIL 6.3332, Rome.

100. CIL 8.2756, Lambèse.

101. CIL 6.2607, Rome.

102. CIL 8.3270, and p.1741, from Lambèse.

103. RIB 1172, Corbridge (Corstopitum).

104. RIB 1350, Benwell (Condercum).

105. CIL 10.7592, Cagliari.

106. BCTH (1904), p.clxi, El-Ghara, in southern Algeria.

107. AE (2012), p.289, Avenches.

108. AE (2013), p.267, Pompeii.

109. ILAf 434, from Naimin-er-Rodoui, near Mateur, Tunisia.

110. ILTun 467, of Haîdra (Ammaedara).

Bibliography

Asskamp, R. & Kühlborn, J.S. ‘Die Ausgrabungen im römischen Gräberfeld von Haltern’, Ausgrabungen und Funde in Westfalen-Lippe 4 (1986), pp.129–38.

Beard, M., North, J. & Price, S. Religions of Rome, vols 1–2 (Cambridge, 1998).

Bertolazzi, R., ‘A New Military Inscription from Numidia, Moesiaci Milites at Lambaesis, and Some Observations on the Phrase Desideratus in Acie’, in Heckel W., Müller S. & Wrightson, G. (eds), The Many Faces of War in the Ancient World (Cambridge, 2015), pp.302–14.

Boschung, D., Antike Grabaltäre aus dem Nekropolen Roms (Bern, 1987).

Burnand, Y., ‘La datation des épitaphes romaines de Lyon’, Inscriptions latines de la Gaule Lyonnaise (1992), pp.21–27.

Clementoni G., ‘Germanico e i caduti di Teutoburgo’, in Sordi, M. (ed.), Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori. La morte in combattimento nell’Antichità (Milan, 1990), pp.197–206.

Cumont, F., Recherches sur le symbolisme funéraire des Romains (Paris, 1942).

Cumont, F., Lux perpetua (Paris, 1949).

Da Costa,V., ‘The Memorialization of the Military Class: Roman Funerary Portraiture and Politics in the Eastern Roman Provinces’, AJA 99 (1995), pp.346–47.

De Visscher, F., Le droit des tombeaux romains (Milan, 1963).

Dentzer, J.-M., Le motif du banquet couché dans le Proche-Orient et le monde grec du VIIe au IVe siêcle avant J.-C. (Paris, 1982).

Doppelfeld, O. (ed.), Römer am Rhein (Cologne, 1967).

Eisner, M., Zur Typologie der Grabbauten im Suburbium Roms (Mainz, 1986).

Fischer, Th., Bockius, R. & Boschung, D. (eds), Die Armée der Caesaren, Archäologie und Geschichte (Regensburg, 2012).

Germania Romana, vol. 3: Tafeln, 2nd edn (Bamberg, 1930).

Gordon, R.L., ‘The Roman Army and the Cult of Mithras: a Critical View’, in Wolff, C. & Le Bohec, Y. (eds), L’armée romaine et la religion sous le Haut-Empire romain (Lyon, 2009), pp.379–450.

Grimal, P., Dictionnaire de la mythologie grecque et romaine, 19th edn (Paris, 1999).

Groslambert, A., ‘Les dieux romains traditionnels dans le calendrier de Doura-Europos’, in Wolff, C. & Le Bohec, Y. (eds), L’armée romaine et la religion sous le Haut-Empire romain (Lyon, 2009), pp.271–92.

Laporte, J.-P., ‘Kabylie (Algerie): le retour de deux soldats maures dans leur foyer’, in Bertholet, F. & Schmidt Heidenreich, C. (eds), Entre archéologie et épigraphie. Nouvelles perspectives sur l’armée romaine (Berne, 2013), pp.213–22.

Le Bohec, Y., La Troisième Légion Auguste (Paris, 1989).

Le Bohec, Y., ‘Tertullien, De corona, I: Carthage ou Lambèse?’, Revue d’Etudes Augustiniennes et Patristiques 38.1 (1992), pp.6–18.

Le Bohec, Y., The Imperial Roman Army, trans. Bate, R. (London, 1994).

Le Bohec, Y., ‘Isis, Sérapis et l’armée romaine sous le Haut-Empire’, in Bricault, L. (ed.), Ier Colloque international sur les études isiaques (Leiden, 2000), pp.129–45.

Le Bohec, Y., ‘L’onomastique de l’Afrique romaine sous le Haut-Empire et les cognomina dits «africains»’, Pallas 88 (2005), pp.217–39.

Le Bohec, Y., L’armée romaine sous le Bas-Empire (Paris, 2006).

Le Bohec, Y. (ed.), The Encyclopedia of the Roman Army (Malden, 2015).

Le Bohec, Y., ‘Cemetery, Military’, in Le Bohec, Y. (ed.), The Encyclopedia of the Roman Army (Malden, 2015), p.190.

Le Bohec, Y., ‘La religion et la guerre au temps de Rome’, in Baechler J. (ed.), Guerre et religion (Paris, 2016) pp.61–69.

Le Bohec, Y. & Wolff, C., Les légions de Rome sous le Haut-Empire (Lyon, 2000).

Lendon, J.E., Soldiers and Ghosts (London, 2005), (trans. 2009, Soldats et fantômes, Paris).

Moretti, J.-Ch. & Tardy, D. (eds), L’architecture funéraire monumentale. La Gaule dans l’empire romain (Paris, 2006).

Perea Yébenes, S., La legión XII y el milagro de la lluvia en época del emperador Marco Aurelio: epigrafía de la legión XII Fulminata (Madrid, 2002).

Perea Yébenes, S., ‘... in bello desideratis. Estética y percepción de la muerte del soldado romano caído en combate’, in Marco F., Pina F. & Remesal J. (eds), Formae mortis: el tránsito de la vida a la muerte en las sociedades antiguas (Barcelona, 2009), pp.39–88.

Peretz, D., ‘Military Burial and the Identification of the Roman Fallen Soldiers’, Klio 87.1 (2005), pp.123–38.

Rankov, B., ‘Christians’, in Le Bohec, Y. (ed.), The Encyclopedia of the Roman Army (Malden, 2015), pp.194–95.

Reuter, M., ‘Gefallen für Rom. Beobachtungen an den Grabinschriften im Kampf getöter römischer Soldaten’, in 19e Congrès du limes (2005), pp.255–63.

Rinaldi Tufi, S., Militari romani sul Reno. L’iconografia degli ‘Stehende Soldaten’ nelle stele funerarie del I secolo d.C., Archaeologica (Rome, 1988).

Ritterling, E., ‘Legio’, RE 12.2 (1925), pp.1211–29.

Sartre-Fauriat, A., ‘Influences exogènes et traditions dans l’architecture funèraire de la Syrie du sud’, in Moretti, J.-Ch. & Tardy, D. (eds), L’architecture funèraire monumentale. La Gaule dans l’empire romain (Paris, 2006), pp.125–39.

Sauron, G., ‘Architecture publique méditerranéenne et monuments funéraires en Gaule’, in Moretti, J.-Ch. & Tardy, D. (eds), L’architecture funéraire monumentale. La Gaule dans l’empire romain (Paris, 2006), pp.223–33.

Stefan, S., Les guerres daciques de Domitien et de Trajan (Rome, 2005).

Susini, G.C., ‘Ricerche sulla battaglia del Trasimeno’, Annuario dell’Accademià Etrusca di Cortona 11 (Cortona, 1959–60).

Toynbee, J.M.C., Death and Burial in the Roman World (London, 1982).

Von Domaszewski, A., Aufsätze zur romischen Heeresgeschichte (Darmstadt, 1972).

Von Hesberg, H., ‘Les modèles des édifices funéraires en Italie: leur message et leur réception’, in Moretti, J.-Ch. & Tardy, D. (eds), L’architecture funéraire monumentale. La Gaule dans l’empire romain (Paris, 2006), pp.11–39.

Witteyer, M., ‘Graäerfelder der Militarbasis und Provinzhauptstadt Mogontiacum-Mainz’, Pro Vindonissa (1997), pp.63–76.