Chapter 5

Georgia L. Irby

Introduction

Health remains a universal concern, no less so for the soldier in the field, from Homer’s warriors to the triage physicians who populate MASH (Mobile Army Surgical Hospital) units. The Roman medical service was, like all other aspects of imperial administration, a model of aggressive efficiency, but it always remained under the shadow of the Greek medical achievement. The approach to maintaining health and treating disease and wounds in the imperial Roman Army was multifaceted, incorporating advances in medical science together with superstition, folk traditions, religion – both local and imperial – and even politics. The centralization and interconnectivity of Roman military posts allowed for the transmission of instruments, practices and findings in medical theory.1 Yet the ill and wounded relied as much on attending physicians as on priests of Asclepius (Latin, Aesculapius) and other healer deities. On the model of Asclepeia (incubation temples to Asclepius) in the Greek-east, physicians and priests were possibly on staff together at the healing sanctuaries of Mars Nodens at Lydney Park in Gloucestershire and Apollo Cunomaglus at Nettleton Shrub, Wiltshire, both in southwestern England.2 Here we shall explore the methods of wound treatment, the evidence for a professional medical corps and the synergy of ‘rational’ and alternative/‘divine’ methods of healing.

The Art of (Military) Medicine

The dichotomy of the medical art is evident in many registers. Gods of healing can moreover bring disease (most notably Apollo), and drugs can either heal, poison or enchant. The Greek word pharmakon (drug, cure, poison) also gives the root for pharmakeia (witchcraft) and related words. In Herodotus, verbs with this stem suggest the act of enchantment: pharmakeuo (‘to administer a drug’), for example, carries the nuance of ‘enchant’, and katapharmasso implies bewitchment with drugs.3 The Latin analogue, venenum (potion, juice, drug, poison), also conveys the force of a magical charm.4 This bolsters the lingering Roman fear of the Greek-trained doctor as unreliable, unprofessional and inept, whose potions were as likely to kill as to heal, as the epigrammatist Martial dryly contends.5 According to tradition, Cato the Elder (234–149 BC) forbade his son from patronizing Greek physicians because they had sworn, so Cato claimed, to kill all foreigners with their medicines.6 Cato (and others) preferred Roman self-sufficiency: his On Agriculture – intended as a guide for the pater familias (the head of the household) in managing an estate – covered numerous practical topics, from planting to the treatment of slaves. Pliny the Elder (died AD 79) viewed his own Natural History in the context of enkyklios paideia (‘ordinary/general education’) which would thus encourage and enable the self-sufficiency of the pater familias.7 Celsus’ work (first century AD) was probably similar in scope.8

It is within this context – the tension between the Greek-trained physician and home-grown folk and religious cures – that medicine at Rome, even in the army, flourished. Israelowich emphasizes the Roman military preference for Greek-trained physicians who were fluent in Hellenistic medical traditions. In the epigraphical record, furthermore, many military physicians have Greek names.9 The health of the Roman soldier was an administrative priority, as evident in criteria for recruitment, training and the paradigm for establishing temporary and permanent camps. The topic is treated at some length in Vegetius’ Epitome of Military Science, a fourth-century AD handbook on the Roman Army. Vegetius tells us that recruits from rural areas are best because they are already inured to the physical demands of military life which, in many ways, overlap the lifestyle of a farmer: i.e., working with iron tools, digging ditches and carrying heavy burdens.10 Stamina is paramount. Unlike their rural counterparts, urban recruits must learn to endure unpleasantly hot or dusty weather, sleep outside or in tents and adopt a frugal, rustic diet. Only after the urban trainee has acquired sufficient physical and mental vigour should he undergo training, much less deployment. Recruits who failed to meet the standards might be discharged, e.g., a certain Tryphon, rejected for poor eyesight at the recommendation of three physicians.11

Vegetius’ account of army health stems from cultural prejudices, practical considerations and theoretical trajectories.12 He considers daily exercise and suitable food more effective than physicians at maintaining a healthy fighting force.13 He also advises on when to march (not in the heat of the sun or in the frost and cold) and where to make camp (in temperate places, neither marshy nor arid, with sufficient water and shade). Vegetius’ assertion that the best recruits hail from temperate climates14 evokes a long tradition of ethno-climatological prejudices that is featured in the Hippocratic corpus (especially Airs, Water, Places), and finds expression in Aristotle, Vitruvius, Strabo (who attributed the rise of Rome to its medial and temperate, yet varied, climate) and others.15 In Vitruvius, we see architecture as an analogue to healthcare. He believed that all human learning was relevant to architecture, and furthermore that architecture (like medicine) must be adapted to climate and topography in order to balance the elements and guarantee harmony with nature,16 just like a Hippocratic physician can balance a patient’s humours through diet, exercise and treatment in order to harmonize the body with its environment. Roman medicine, however, largely eschewed humourism, preferring instead a pragmatic, mechanistic model of the body.

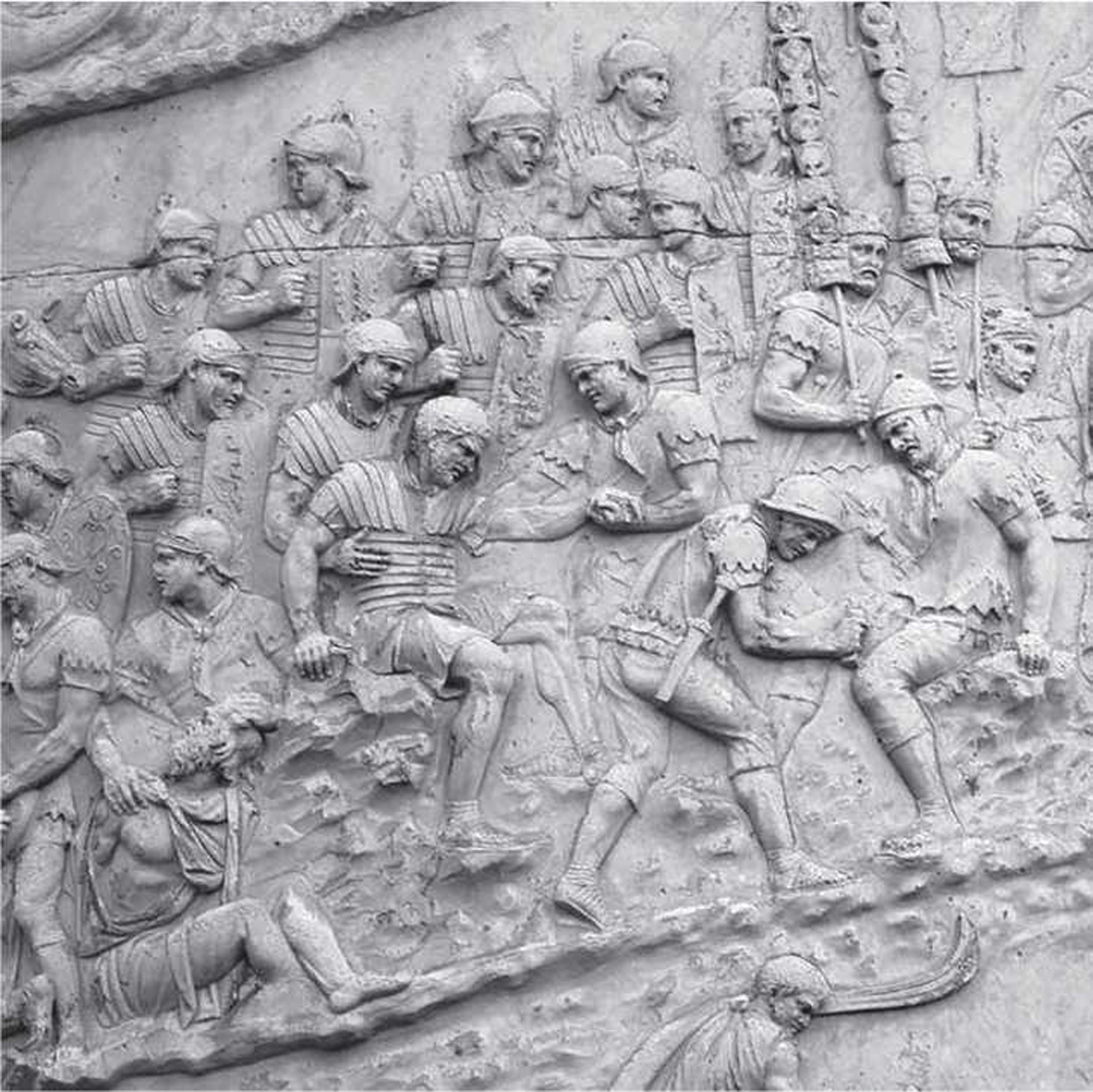

In order to avoid ‘the unsalutary dangers’ mentioned by Vegetius, campsites were painstakingly selected.17 In permanent camps we find sanitation systems, continuously flushed latrines, bath houses and even permanent drill halls where soldiers could train during inclement weather.18 Many specializations are evident in the medical staff attached to legions: seplasarii who oversaw medical ointments; marsi to treat poisonous bites;19 vigiles attending to the convalescent; administrative librarii who kept accounts; and veterinarii and pecuarii for livestock.20 In addition, more highly trained medici, with either short contracts or permanent commissions, also specialized in delicate procedures such as surgery (medici chiurgi), internal medicine (medici clinici) or eye complaints (medici ocularii), which were all too common because of the smoke produced from oil lamps.21 The bearded, trousered medic on Trajan’s Column was probably attached to an auxiliary cavalry unit (see Figure 5.1).22

Figure 5.1: Battlefield triage. Trajan’s Column, spiral 6d (Panel 40, Scenes 102–03). (Courtesy Art Resource 27439)

Battle Wounds and their Treatment

The descriptions of battlefield wounds are often vivid. Assailants usually aimed for exposed or particularly vulnerable areas, such as the throat/neck, chest or an unprotected thigh,23 and armour was designed to protect vital body parts.24 In Virgil’s Aeneid, battle scenes are particularly rich. The first casualty of Aeneas’ war in Italy was a young Italian lad, Almo, whose ‘wound clung beneath his throat and blocked with its blood both the path of his voice and his tender life’.25 A Trojan ally, Phegeus, was injured when a broad lance struck at him in an unprotected area (retectum). Turnus then swept his sword between the ‘lowest rim of the helmet and the breastplate’s upper edge’ (where the neck is exposed) to decapitate Phegeus.26 Among Camilla’s victims was Butes, whom she struck between the corselet and helmet, a vulnerable bare spot ‘where the neck shines through’.27 Camilla herself died from a spear point ‘lodged deep in her chest, between her bones and near her ribs’.28

Informed largely by contemporary practices, Latin poets delighted in the gore of various types of wounds. Camilla brutally dispatched Orsilochus with her axe, striking through his armour and bone until his ‘wound moistens his face with his brains’.29 Silius Italicus gives us the consul Flaminius, impaled by a javelin while fighting against the Carthaginians at Lake Trasimene (217 BC). The missile pierced through his naked ribs, and Flaminius, who could see the protruding point, tried to dislodge it.30 Lucan describes the gruesome effects of the bite of the seps, a poisonous serpent whose toxin was thought to cause thirst: the skin around the puncture mark shrinks to reveal the white bone until the wound seems to take over the body, while poisoned blood permeates the entire body, melting off the calves, stripping the skin from the knees and rotting the muscles of the thighs until a black discharge drips from the groin. The belly snaps and the bowels burst out; every part of the body (ligaments, lungs, chest cavity, all the vital organs) is exposed, and the limbs and head melt ‘more quickly than snow on a hot day’.31 The etymological connection of ‘seps’ with putrefaction informs Lucan’s description of the venom as causing ‘instant liquefaction’.32 Depending upon the species and virulence of its poison, effects of envenoming serpent bites can include severe necrosis of localized soft tissue and skeletal muscle, though not on a scale as described by Lucan.33

The average soldier seems to have possessed some rudimentary training in first aid. Galen asserts that most soldiers knew how to staunch blood-flow from severed veins and arteries.34 The skill probably extended to the civilian population, especially slaves on administrative staffs. Cornelius Scipio Salvito’s householders attempted to staunch a self-inflicted dagger-wound that resulted in Scipio’s death in North Africa in 46 BC.35 In Lucan, Caesar staunched the wounds of his soldiers on the battlefield in Thessaly.36 In Silius Italicus, the wounded Serranus, fighting against Hannibal, lamented that no companions survived to tend his wounds.37 Even commanding officers tended to the wounded, including Germanicus38 and his wife, the strong-willed Agrippina.39 Trajan reputedly tore his own cloak into strips to provide bandages for the wounded near Tapae in battle against the Dacians in AD 101/102.40

Trajan’s Column includes a triage scene that shows Roman and auxiliary troops tending to two wounded men whose faces grimace in pain (see Figure 5.1). In right profile, a bearded soldier wearing lorica segmentata struggles to stand up with the help of two legionary soldiers; the veins of his right arm are visible as he clutches the rock on which he sits. To his left, a wounded cavalryman, in left profile, also grasping his seat, rests his right hand on the back of a bearded medic who wraps the injured man’s left leg. The leftward medic and his patient both wear trousers, perhaps attesting non-Roman status. Where possible, wounded troops would be removed from the field, often in wagons,41 or at least withdrawn to the rear line to be treated either by fellow soldiers or trained medici.42 Troops cared for the wounded in North Africa,43 and healthy soldiers tended to the wounded after Otho’s defeat at Bedriacum in AD 69.44 Caesar withheld caring for his wounded in 57 BC against the Alpine Seduni and Veragri, whose large supply of fresh troops prolonged that battle,45 as did Quintus Cicero, under attack by the Nervii in Britain in 54 BC.46 But Caesar delayed marches for the benefit of the wounded when expedient, as after devastating setbacks at Dyrrhacium.47 The loss of medical supplies could prove disastrous, so precautions were taken to convey these valuable stores in the middle of the column for safety and ease of access.48

Most battlefield wounds were caused by trauma or missiles. Celsus punctiliously explicates the treatment of missile wounds. Six centuries later, Paul of Aegina would repeat Celsus’ wound therapies, thereby endorsing their efficacy.49 Celsus considers differing projectile shapes, angles of entry, depth of penetration and proximity to large blood vessels or vital organs (which can render battlefield triage tricky and troublesome: magno negotio). Arrow extraction should be performed only by experienced medics with practical training and exact anatomical knowledge.50 Rufus of Ephesus (late first century AD) advises waiting for a skilled surgeon to remove arrows.51 The wounded soldier, nonetheless, instinctively either tries to pull out the arrow himself (as had Flaminius, Pallas and Camilla),52 or he seeks help from a fellow soldier, as had the guardsman Verennianus, who enjoined Ammianus Marcellinus to remove the arrow lodged in his thigh at Amida in AD 359.53

Celsus recognizes that only (un-barbed) projectiles lodged in superficial tissue should be removed at the entry point. Such projectiles can be withdrawn by carefully enlarging the wound with a scalpel, so the tip can be safely retracted. With this method, aggravation of the soft tissue is limited, thereby reducing inflammation. Otherwise, the projectile must be forced through, a procedure that facilitates healing since medicaments can be applied at each puncture. Specialized instruments facilitated arrowhead removal, such as the dioster (‘impellent’): a rod whose pointed end was used to extract tips with sockets or whose hollow end was used for arrows with ‘tails’.54 Regardless of which end of the arrow was to be extricated first, the surgeon must take care not to prick any blood vessels or sinews. Celsus thus recommends a blunt hook to hold delicate vessels away from the scalpel.55

Celsus provides instructions for removing various types of projectiles, including barbed arrows, broad-bladed weapons and lead balls.56 In Celsus, we discern an understanding of the physics of projectiles (the greater the force/speed of the hit, the deeper the penetration) and the dangers of removing barbed arrows at the entry point, as this could result in further (perhaps even fatal) irritation. Pliny mentions the barbed reed arrows, in use in the East, whose tines cannot be removed.57 Paul of Aegina describes particularly nasty arrowheads (with hinged barbs that unfold when extraction is attempted) and those featuring small bits of metal (of unknown shape, fitted into grooves on the tip) that remain in the wound when the tip is withdrawn.58

The latter type is attested as early as 69 BC during the Third Mithridatic War, when Lucullus encountered a variety of poisoned doublepointed arrowheads whose second tip remained in the wound.59 Whether such arrowheads existed at all or were designed expressly to obstruct missile extraction remains contested.60 Celsus, nonetheless, describes a specialized instrument ‘like a Greek letter’ (upsilon) with which to stretch the flesh in order to remove barbed arrows safely (like a gynecological speculum; see Figure 5.2).61

Intact arrows should be pushed through and drawn out at the other side. Shafts, however, were designed to break off, leaving the tip in the wound, which even an experienced surgeon might miss.62 In such cases, Celsus recommends forceps to extract the tip. If a broken arrow must be removed at the entry point, the medicus should use his forceps to snip off any short, fine tangs, or he should wrap larger barbs with reeds and then withdraw the point so as not to tear any more flesh.

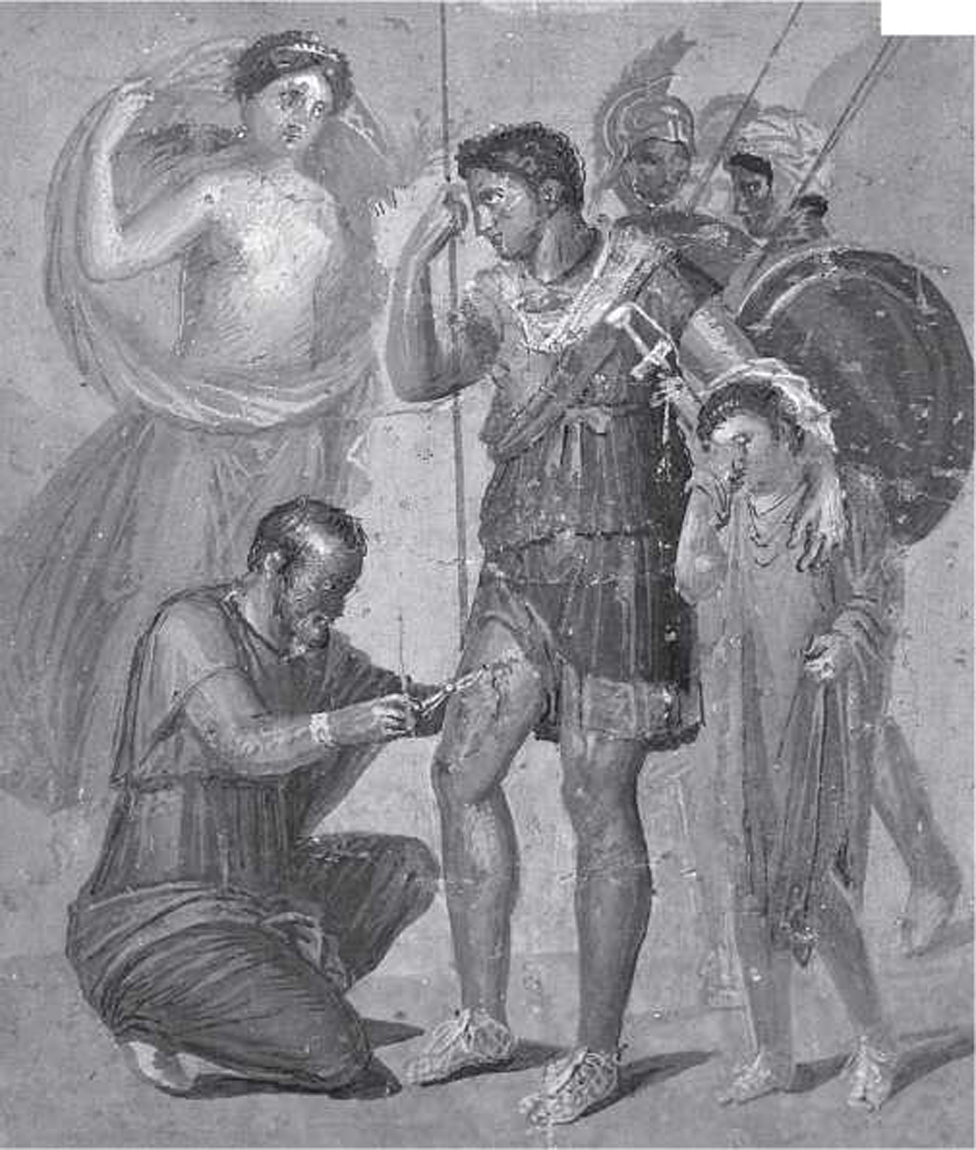

A fresco from Pompeii depicts an attempt to extract an arrow (see Figure 5.3).63 The Trojan healer Iapyx tries to remove a stray missile lodged in Aeneas’ thigh: Iapyx ‘pulled at the dart with his forceps in vain’, receiving no assistance from his patron, the healer god Apollo.64 The fresco shows Iapyx bracing his left hand behind Aeneas’ right thigh while he works at the point with his forceps (the arrow had broken off at the shaft). The scalpel is not shown. The tip is ultimately removed only through divine intervention when Aeneas’ mother, Venus, suffuses the river with dittany, a therapeutic, aromatic herb from Crete, popular for extracting arrows from both humans and goats, either imbibed or applied topically.65 When Iapyx bathes Aeneas’ wound with this analgising water, the arrow-head slips out and Aeneas’ strength returns. Thus in Virgil we see a distinction between ‘rational’ healing as overseen by the cults of Apollo and Asclepius and divine healing which can be bestowed by any god (as we shall see below).

Figure 5.2: Bivalve rectal speculum. (Courtesy of Naples Archaeological Museum, inv. no. 78031)

For broad blades, Celsus recommends removal at the entry point with a specialized probe, the Dioclean cyathiscus (‘spoon of Diocles’, attested only in Celsus; see Figure 5.4). Celsus describes the instrument and its use:

‘[The cyathiscus] has iron or copper blades. At each edge of one of the blades there are hooks turned downwards. The other blade is curved, moderately angled, and perforated. The latter blade of the cyathiscus is positioned next to the weapon and then underneath until the sword point is reached. The instrument is torqued a little bit so that the weapon catches on the aperture. When the tip is in the hollow, fingers positioned under the hooks of the first blade simultaneously extract the tool and the weapon.’66

Figure 5.3: Iapyx tends Aeneas’ arrow wound (Pompeii, House of Siricus, National Archeological Museum of Naples, inv. 9009). (Courtesy Art Resource 73149)

Probing was often the only feasible diagnostic method for missile wounds. Probes are frequently mentioned by medical authors, and they are among the most common medical finds in both military and civilian contexts.

Extracting lead, pebble or shell ballistae lobbed by slingers has its own challenges. Ideally, an intact ball should be removed through its entry point by a forceps after the wound has been opened up. If the ballista is fixed in a bone, tooth extracting methods are applied:67 the ball is jostled out by fingers or forceps, or a blow by ‘some instrument’ will (hopefully) dislodge a tenacious ball. Otherwise, the medic must resort to trepanation by boring a V-shaped hole into the bone. In the case of ballistae that have been lodged into joints, Celsus recommends stretching out the sinews at either end of the joint to create space within the joint, thus allowing for access to the ball, while, of course, taking care not to cause further injuries.

Figure 5.4: Dioclean cyathiscus. (Image taken from Bliquez, 2015: figure 43A)

In addition to missile removal, the army doctor had to be proficient at treating various types of trauma, including flesh wounds, head trauma, bone injuries and complications such as haemorrhaging and inflammation, which could lead to death.68 Instruments excavated from military sites across the Roman Empire speak to a variety of medical activities: surgical knives, scalpels, forceps, spoon scoops, hooks, needles, bone scrapers, cupping vessels, bone levers, cauterizers, male and female catheters, many types of probes (including ear probes for removing foreign objects from the ear), collyrium stamps, ointment pallets and medical boxes.69

Biological and chemical weapons are also known, cited by both medical and nonmedical writers.70 Scribonius Largus, who collected 271 pharmaceutical recipes at imperial request (ad 47), recommends Cassius’ multi-ingredient salve for treating, in particular, wounds caused by poisoned arrows.71 The Dacians and Dalmatians poisoned their arrow tips with helenion and ninon, otherwise obscure.72 Silius Italicus refers to ‘twice harmful missiles’ dipped in ‘hydra’ venom in North Africa and the poisoned javelins of the Nubians.73 As we saw above, Lucullus contended with poisoned arrows in Asia. By the late first century AD, chemical warfare seems to have been common, and Rufus advises military leadership to inquire about poisoned arrows, which in his time became increasingly virulent, killing ‘even if they make a small wound’. Rufus also warns that arrows, especially poisoned ones, should be removed, but only by experts.74 Celsus simply advises the quick extraction of the poisoned projectile and employment of the same techniques already recommended for serpent bites.75 Paul of Aegina more helpfully prescribes the removal of discoloured, septic tissue, which ‘stands out clearly’ from healthy tissue.76 Galen and Paul also knew that arrow poison was fatal only once it reached the bloodstream, probably as understood in the context of poisons used for hunting.77 On the strength of this fact, Lucan’s Cato tried to persuade his dehydrated troops to drink from a pool crawling with venomous dipsades.78

Before bandaging, the wound might be dressed with linen or wool medicated with vinegar, wine, oil or a pharmaceutical cocktail.79 In On Medical Matters (de Materia Medica), Dioscorides of Anazarbus (first century AD) describes numerous pharmaceutical ingredients, citing wound treatment as among the particular uses of over sixty plant, animal and mineral medicinals that serve as coagulants,80 anti-inflammatories,81 agglutinizers82 and cicatrizers (promoting the growth of scar tissue to heal a wound).83 Highly esteemed for its wound-curing properties, centaury (Centaurea centaurion L.) is recommended for its agglutinating and astringent properties.84 Dioscorides enthusiastically recommends amorge, the humble sediment from pressed olives: ‘there is nothing like it for toothaches and for wounds when smeared with vinegar, or wine, or honey mixed with wine’.85 Other wound remedies were made from the plastered leaves of the chaste tree – also used for sprains – the opium poppy mixed with vinegar, rosemary, gums from fruit trees and lycium for festering wounds. Devoting five books of his thirty-six-book encyclopedia to pharmaceuticals, Pliny considers hyoseris (a member of the dandelion family) ‘a splendid remedy for wounds’ and poterion ‘a wonderful wound healer’.86

The professional medical corps were likely to employ more complex treatments. Scribonius Largus includes descriptions of twenty different dressings (emplastra) for a variety of wounds from ‘fresh’ (recens) to ‘moderate’ (mediocria), endorsing in particular Glycon’s compounded ‘Isis’ dressing which overcomes ‘all ailments’ (compounded from burnt copper, verdigris, frankincense, myrrh, aloe, resin and other ingredients).87 Two of Thrasea the Surgeon’s wound recipes work ‘marvellously’ (mirifice). Among other ingredients, Thrasea’s black plaster calls for wax, pitch, roasted resin, Zacynthian asphalt, white lead, verdigris, copper pyrite and alum.88 Scribonius asserts the plaster’s efficacy for dangerous wounds (periculosa vulnera) in ‘all men’, and gladiators in particular. Nowhere does Scribonius single out treatments for soldiers, despite his participation in the British invasion (Claudius’ reign was largely peaceful).

Military sites might include gardens for growing medicinal herbs, as long believed by the folk who lived along Hadrian’s Wall:

‘The Roman souldiers of the marches did plant heere every where in old time for their use, certaine medicinable hearbs, for to cure wounds: whence it is that some Emperick practitioners of Chirugery in Scotland, flock hither every yeere in the beginning of summer, to gather such Simples and wound herbes; the vertue whereof they highly commend as found by long experience, and to be of singular efficacy.’89

Chive (allium schoenoprasum Linnaeus) has been found near Walltown along the line of Hadrian’s Wall.90 At Neuss in Germany, medical staff were cultivating centaury, henbane (Hyoscyamus sp. Linnaeus), St John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum Linnaeus), plantain (Plantago major sp. Linnaeus), and fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum).91 Most pharmaka, however, were imported.92 Legion II Adiutrix, stationed near Budapest, received duty-free wine ‘for the account of the hospital’.93 Horehound-flavoured wine (Marrubium vulgare Linnaeus) was imported to Carpow in Scotland in the early third century ad. An Egyptian papyrus also records a contract (dated to AD 138) for ‘plain white blankets, six cubits by four, with finished hems’, intended, perhaps, for the legionary hospital in Nicopolis.94 Celsus had also prescribed special ‘easy to digest’ diets for invalids. At Neuss, such foodstuffs have been found, including lentils, peas and figs (not native to Germany but with a number of medicinal applications).95 Radish oil was popular for bedsores and phthiriasis, and soldiers requested their own supplies of it from family and friends.96

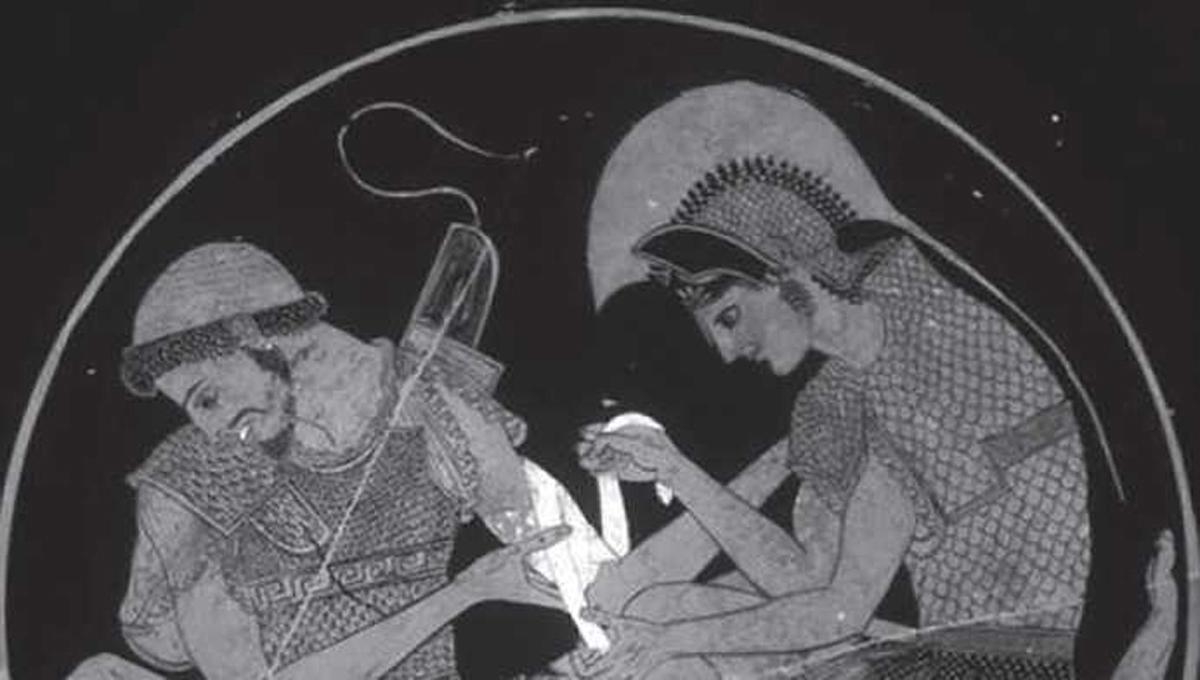

Large wounds were sutured with flax or linen thread ‘so that the scar might be less wide’,97 and Galen recommends taking precautions to heal the wound before the thread ‘runs off’ (that is, before it starts to rot).98 To facilitate cicatrisation, the medic’s arsenal included murex snail with drying and cleansing properties; cyclamen root boiled in old olive oil, vervain with honey, and burnt copper, one of the ingredients in Glycon’s ‘Isis’ plaster.99 Once the lesion was treated, a dressing might be applied, especially to larger injuries. We have already seen that most soldiers would have possessed this skill, and that even commanding officers (or their wives) might attend to soldiers when battles went badly and medics alone were insufficient in caring for the injured. The scene is recorded in artwork, most famously on the interior of a kylix from Vucli (c.500 BC) by the Sosias Painter, showing Achilles dressing the wound of his friend Patroclus (see Figure 5.5).100

An arrow, it can be assumed, has just been removed from Patroclus’ upper left arm (an arrow appears almost parallel with Patroclus’ bent right leg). Supporting his injured arm on his left thigh, Patroclus holds one end of the white bandage in place with his right hand while a crouching Achilles wraps the arm. It is an intimate scene fore-fronting the pathos of Patroclus’ impending death. We note also that the auxiliary medic on Trajan’s Column holds a bandage roll. Military bandagers (capsaraii) are known at Neiderbeiber, Germania Superior,101 Carnutum,102 Brigetio103 and Lambaesis.104 Soldiers were even known to bandage healthy limbs in order to feign injury and avoid fighting.105

Works entitled On Bandages are ascribed to Soranus and Galen, but the topic is addressed in most medical writers, including Celsus, who recommends cutting bandage-linen wider than the wound.106 Bandages were sometimes wrapped from one end (as with our auxiliary soldier on Trajan’s Column) or from the middle (as was Patroclus’), depending on the degree of symmetry of the lesion – Celsus seems as concerned with aesthetics as treatment. The proper wrapping with the correct pressure facilitates healing and diminishes cicatrisation. Celsus is also concerned with the patient’s comfort. He advises fewer turns of a bandage in the (hot) summer, more turns in the winter and a needle-and-thread finishing since ‘a knot hurts the wound’. Fanciful names (‘four-legged’, ‘hare with ears’) suggest that wrappings could be elaborate: on Patroclus (see Figure 5.5) we see symmetrical crisscrossing wraps.107 Salazar notes that busy field surgeons probably eschewed such elegances and may have delegated the task to assistants.108

Figure 5.5: Achilles tends to Patroclus’ wounds; Berlin F2278. (Courtesy of Art Resource 169160)

The Professional Military Corps and Army Hospitals

During the Republic, military medicine was largely ad hoc, and no evidence suggests a formalized Republican-era medical corps, military or civilian. Scarborough laconically concludes: ‘The problem of the wounded would not be too important if the Roman legion won its battles; those who were victorious in ancient warfare usually did not lose many men, whereas those who lost normally lost everything.’109 Often included on the private staffs of provincial governors and commanders in the field were physicians, whose attentions may have extended to the ranks.110 An offhand remark in Cicero suggests that medics, at the very least, were common in the legions by the mid-first century BC: through their training, soldiers learned, among other things, to trust the medicus to treat their wounds in battle.111 Medicus, however, is an ambiguous term, and may here simply refer to a soldier skilled at triage.112 Vegetius tells us nothing more than that army doctors fell under the camp prefect’s authority.113 Nor does Caesar mention them directly, despite all his concern for the welfare of his men. Caesar’s medici may have been soldiers who also happened to possess some medical skills.114 But the dictator did confer citizenship on practising physicians at Rome, an economic incentive likely intended to attract skilled medical personnel to the city (citizenship included tax exemptions) and perhaps to improve conditions for soldiers in the field.115

Caesar’s privileges to the medical corps were extended by Augustus, Vespasian and Hadrian. Whether the military medical service became professionalized remains a point of contention – the evidence is hardly conclusive.116 On the fronts in Germany and Pannonia, Tiberius made his personal physicians and supplies available to sick and wounded officers.117 We saw above that a fellow soldier called upon Ammianus Marcellinus to remove an arrow. Ammianus also mentions ‘experts in removing arrows’ and ‘experts in healing’ who tended to Roman troops wounded by Parthian arrows. But he does not specify if his experts are Roman Army doctors, local healers or trained laymen.118 Nonetheless, it is the extraordinary, not the ordinary, that merits comment. Far from disproving the existence of a standing medical corps, such accounts only indicate that the medical resources to hand were insufficient in the heat of battle. Given Roman efficiency and self-reliance – soldiers are wounded in battle, and everyone falls ill at one time or another – it is reasonable to assume that a military medical service existed, regularized under Augustus when the Roman Army became a standing professional service.119 But we cannot be certain of its precise organization or status. Members of the military medical corps were bound by the military oath but, along with other specialist ranks, they enjoyed exemption from combat and routine duties.120 Nutton argues that the legal recognition and protection of the military medicus ‘implies a formal organisation of the medici comparable with that of the administrative staff of the legion or with other specialists’.121 Yet Galen bemoaned the poor skills and anatomical ignorance of the medics on the front during Marcus Aurelius’ campaigns against the Marcomanni.122 ‘Professional’, however, does not guarantee excellence, and Marcus Aurelius’ medical corps may have been hastily recruited and hurriedly trained.

Nearly ninety medical personnel attached to the imperial Roman Army are attested.123 Famously, Dioscorides wrote of his ‘soldier’s life’, leading some to speculate that he was a practising army doctor.124 Dioscorides does not, however, call himself a ‘soldier’ – he may have simply considered his occupation difficult and disciplined.125 Scribonius Largus tells us that he travelled with Claudius’ household during the British invasion in AD 43, but we do not know if he was an official army doctor or a personal physician to a high-ranking officer.126 The historian Statilius Crito, who also wrote on pharmacy, saw action on the Danube with Trajan.127 Advances in medical knowledge, furthermore, were made by the Roman Army medical corps. Galen recommends the headache cure of the army doctor Antigonus and the eye-salve of the classis Britannica’s oculist Axius.128 The antiscorbutic properties of radix britannica were likely learned by Germanicus’ army doctors from locals in Frisia.129 Celsus’ barbarum plaster for flesh wounds was also a campaign discovery. Its ‘foreign’ name (barbarum) suggests a non-Greco-Roman origin.130 Furthermore, Celsus recognizes that those who treat the bloody wounds received by gladiators and soldiers in battle are far more knowledgeable than civilian medics regarding internal medicine.131

Although most practising physicians underwent little formal training (Galen is among the exceptions), evidence suggests some mechanism for medical training in military contexts. An inscription from Lambaesis in Algéria attests an organization of Roman medical military personnel that includes ‘student bandagers’ (discentes capsariorum) undergoing instruction.132 Some trained medical doctors may have joined the army after receiving civilian training, such as Anicius Ingenuus, a medicus ordinarius of the first cohort of Tungrians at Housesteads in northern England who died at age 25, too young to have served long enough to attain a rank equal with centurion.133 There were also problems with medical pretenders, and efforts were made to stem such abuse with free healthcare for soldiers in the third century ad.134

The military ‘hospital’ (valetudinarium; plural valetudinaria) has its origins with Julius Caesar, who established garrisons to accommodate soldiers who could not march with the ranks. Even earlier, attentive generals provided special accommodations for convalescing soldiers in order to ensure esprit de corps.135 Before such hospitals were built on any scale, the wounded might be billeted with civilians, a practice that continued into the third century ad.136 Whether the valetudinarium was a regular feature of permanent legionary camps is debated, and some of the literary evidence may have been over-interpreted.137 Nonetheless, a description of Trajanic-era valetudinaria survives in Hyginus Gromaticus’ On Military Camps. With careful attention to lighting, water supply and the setting in order to provide convalescents with maximum quiet, away from the regular bustle of camp activities, Hyginus’ legionary valetudinarium accommodated about 200 patients.138 Valetudinaria are also attested epigraphically.139 Existing remains show a standard plan and position (see Figure 5.6).140

The earliest legionary hospital, at Haltern in Germany, is the single exception, resembling instead a collection of tents.141 Valetudinaria usually included facilities for kitchens, wards and, perhaps, operating rooms.142 An extant duty roster from Vindolanda provides a tantalizing glimpse into the military hospital ward: thirty-one men were cited as unfit for duty for various reasons (the ever-common eye complaints, illness and sundry injuries, not all inflicted in battle).143 Papyri from Dura-Europos ambiguously designate men on medical leave144 or otherwise unfit for service.145 There are reports of food poisoning, scurvy and even prosthetic limbs.146

Medical and administrative duties were time-intensive and demanding, as we hear from the brothers Serenus and Marcus stationed together in Alexandria in the third century ad. In a letter to his mother, Marcus described caring for dying, wounded and battle-fatigued men, and after battle against the Anoteritae (whose precise location remains unknown) conditions remained turbulent. Marcus here seems to chronicle men suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.147 Serenus berated his mother who, naturally, wanted a visit from her sons, but they were simply too busy to leave their post.148

Figure 5.6: Remains of the legionary valetudinarium at Housesteads. (Photo courtesy of Carole Raddato)

‘Alternative’ and Divine Healing

Despite the efficacy of pharmaceutical and surgical cures, medicine (civilian and military) was never divorced from ‘religion’ or ‘magic’ in the ancient world.149 Even Galen does not categorically deny the validity of ‘alternative medicine’. Celsus alone seems to deny theodicy (illness as divine punishment) and divine healing.150 Most gods had some healing associations: we have already seen Venus aid her wounded son. Minerva is attested as ‘ Medica’ into the third century AD,151 and Jupiter carries the epithet ‘Healing’ (Valens) in Lambaesis in honour of the health and well-being of Septimius Severus’ household.152 Soldiers invoked an array of gods for their own health (salus, which consists not just in health but also prosperity and safety). We find an honorific dedication to the Augustan Mercury (a popular god with soldiers and civilians in the provinces) erected for the health of Marcus Aurelius (and the dedicator’s own): thus, by expressing his allegiance to the emperor, the centurion Marcus Annius Valens linked his own health with the imperial family.153

Many (formulaic) entreaties were made proactively on behalf of the community. The Augustan Mars was invoked for the health of the soldiers (pro salute militum) and their commander.154 Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Juno and Minerva (together comprising the Capitoline Triad which protected the city of Rome), plus the genius (protective spirit) of Mogontiacum (Mainz), were invoked by the praetor Marcianus Vercellis in AD 192 for the health and safety of his legion.155 Human health was thus closely linked with geography and the favour of local deities.156 Cassius Troianus (the nomen suggests an Eastern origin) fulfilled a vow to Fortune on behalf of the health of his fellow soldiers.157 Jupiter Dolichenus, associated with Hygieia in Africa, was entreated for the health of German allies and a legionary vexillatio at Piercebridge in northern England,158 for a cavalry wing in Pannonia Superior159 and for Legion XIII Gemina (and the perpetual imperium of Rome!) at Apulum in Dacia.160 The cult of Jupiter Dolichenus was especially popular under Septimius Severus and his son Caracalla.161 Thus, human health is politicized, hinging also on the success of the reigning emperor and the strength (imperium) of Rome. The popular Eastern salvation deity, Mithras, was entreated on behalf of the watch commanders and armourers of two legions in Pannonia Superior, perhaps as a thank offering for initiation into the cult.162 The popular horse goddess Epona was also invoked for human healing and protection.163

We can only speculate that individuals, usually ranking officers but occasionally freedmen, who invoked gods for the health (pro salute) of legionary legates, were on army or personal medical staffs. Names of these third-party dedicators sometimes suggest an Eastern origin. But we must not dismiss the possibility of medically trained Roman officers. The centurion Caius Iulius Africanus – a thoroughly Roman name – invoked Diana Regina and Apollo for the health of his legate Vitrasus Pollio.164 Africanus here could have been either a medical officer or a concerned friend. The centurion Aelius Artemidorus (whose nomen is Greek) may also have been a personal friend of his legate, Statilius Severus. Artemidorus fulfilled a vow to Diana Regina and Apollo on behalf of the health of Statilius and his children.165 The tessarius (watch commander) Aurelius Zoticus (a Greek nomen) and his fellow soldier Aurelius Bello (a Celt?) invoked Silvanus, the Roman deity of the greenwood, for the health of their centurion, Julius Licinus.166 Lucius Messius Primus, a grain supply officer in Moesia Superior, called upon Hercules for the health of his legate.167 An unnamed freedman entreated Neptune for the health and return of his patron, a centurion of Legion III Augusta.168 The freedman Aufidius Eutuches (Greek for ‘Good Luck’) fulfilled his vow to the multi-valent Sulis Minerva (below) for the health and well-being of his centurion.169 Any of these entreaties may have been made out of friendship, respect or professional duty. The inscriptions do not betray the motivations of their dedicators.

Stones attest vows fulfilled by soldiers and officers to many deities for personal health, among them: Liber,170 Mithras,171 the Magna Mater172 and Heliopolitanus, a north African deity syncretized with Jupiter and whose popularity rose with the Severan dynasty.173 Although most of the inscriptions are formulaic, one intrigues. The veteran Caius Iulius Agelaus invoked the underworld gods Pluto and Proserpina ‘for his own light’ (pro lumine suo) and for the health (pro salute) of himself and his wife Meletenis.174 Little is known of the cult of Pluto and Proserpina, whose associations included fertility and wealth, but there is a clear correlation between the dark underworld and the world of light. Those who return from the dead (Alcestis, Hercules) are often described as returning to ‘light’; birth, furthermore, is an act of coming into the light.175 The Hippocratic On Regimen gives expression to the dichotomy, repeating the folk belief that ‘one thing increases and comes to light from Hades, while another diminishes and perishes from the light into Hades’.176 Given the singular lumine, we assume that Agelaus has recovered from a near-death illness or injury.

The connection between healing and the divine remained a strong topos in Greco-Roman literature, for example the plague sent by Apollo to punish Agamemnon to Aeneas’ physician, Iapyx, much esteemed by Apollo and gifted with the ‘silent and inglorious’ art of healing.177 Pliny declaims that even in his own time, cures were sought from oracles.178 Gods bestowed health or illness in response to obeisance or insult, and theodicy is widely-attested into the Roman imperial era.179 Hippocratic (rational) medicine and the temple cult of Asclepius arose nearly simultaneously in the fifth century BC in response to the same stresses and goals: to establish medical orthodoxy over magical alternatives.180 And Asclepius and his descendants gained divine status precisely because of their ability to heal.181 The aims, scope and methodologies of temple and secular physicians were symbiotic. Gods were called upon to witness the Hippocratic oath; Hippocrates allegedly copied out the iamata (healing inscriptions) at the temple of Asclepius in Cos; and physicians were on staff at healing shrines.182 This synergy endured into the second century AD, on evidence from Pausanias, Aristides and Philostratus, who often attest religious healing in temple contexts.183

Asclepius was widely worshipped at incubation shrines (Corinth, Cos, Pergamum and Epidaurus among the most famous), where the god would visit his sleeping worshippers, and his priests and physicians prescribed a variety of techniques, including exercise, diet, healing dreams and even performative rites, to treat the patient holistically.184 Prognostication by dreams – especially those sent by Asclepius – was an integral part of ancient medicine from the Hippocratics onward.185 A treatise on symptomatic dream interpretation, attributed to the Hippocratic school, informed the medico-pathological approaches of later medical writers, including Rufus and Galen, who both believed that the soul could reveal humoral imbalances in the body and that the god’s capacity to heal through dreams was genuine. Galen claimed that he was able to treat his own abscessed hand with instructions from the god (becoming afterwards the god’s servant).186 His fragmentary treatise on diagnosis from dreams guides readers in the use of dreams to investigate and restore humoral balance.187 To Galen’s mind, dreams could be empirically traced to the patient’s habits, diet or environment.

Incubation and dream interpretation formed the core of temple healing. A full discussion of Asclepius’ cult is not possible here, but about forty inscribed altars attest Asclepius in Roman military contexts. Most of the inscriptions are formulaic, but one implies that a soldier received a cure from an Asclepius-sent dream (ex visu). Caius Julius Frontonianus, a veteran beneficiarius consularis (an officer seconded to the governor’s staff), supplicated Aesculapius, Hygieia and the ‘other healing gods and goddesses of this place’ (Apulum in Dacia) in thanksgiving for the restoration of his eyesight (redditis sibi luminibus).188 No Asclepeium is known at Apulum, but Asclepius did heal through intermediaries,189 nor are ‘house-calls’ entirely unfeasible. Once again, local deities are a powerful force whose favour can regulate or deny well-being.

Although there is no epigraphical proof that Roman soldiers in particular sought cures by incubation in temples of Asclepius, empirical and divine approaches are integrated in Roman military contexts. Roman military medics commissioned at least six Asclepius dedications, including the earliest epigraphic evidence of a Roman Army doctor (ad 82). Sextus Titius Alexander, a medicus (whose cognomen is Greek) attached to the Praetorian Guard at Rome, gave a gift of an inscribed altar to Asclepius and Health (Hygieia).190 At Vinovia (Binchester) in northern England, a medicus fulfilled his vow to Aesculapius and Health for the well-being of his unit. The slab (late second or early third century AD) shows both gods in bas-relief (see Figure 5.7).191 Marcus Rubrius Zosimus, a medicus of a cavalry cohort stationed at Obernburg-am-Main, invoked Jupiter Optimus Maximus, Apollo, Aesculapius, Health and Fortune for the health of his prefect Lucius Petronius Florentinus, whom, we assume, had fallen ill but has subsequently recovered.192

Figure 5.7: Aesculapius and Hygieia at Binchester: RIB 1028 (Heidenreich 2013: 91).

Some of these invocations were honorific, for the well-being of the sitting emperor and his family. At Aquae Flavianae in Numidia, for example, the centurion Marcus Oppius Antiochianus entreated Aesculapius and Hygieia for the health and victory of Pertinax (ad 193), an expression of Oppius’ allegiance to an emperor during civil war.193 In AD 227, the imperial bodyguard invoked the obscure Asclepius ‘Zimidrenus’ for Severus Alexander’s health.194 At Aquincum, the centurion Domitius Victorinus honoured the ‘health of the emperor’ with a neatly carved altar to Aesculapius, Hygieia, Silvanus and the gods who ‘preserve’ (Conservatoribus).195

Asclepius was also invoked as ‘Augustan’, an epithet that integrated him with the imperial house and its cult, thus politicizing the healing cult. At Apulum, for example, Olus (Aulus?) Terentius Pudens Uttedianus, legate of Legion XIII Gemina and governor of Raetia, invoked the Augustan Heaven (Caelesti Augustae) and Augustan Aesculapius (Aesculapio Augusto), together with the genius of Carthage and the genius of the Dacians. Uttedianus invoked the protective spirits of two locales: Dacia (the province where he was currently stationed) and Carthage (perhaps a former post or his home?).196 The date of the stone is contested, but it was likely erected during a period of war or political instability.197 Uttedianus thus adroitly linked his own health and success to both his geographical location and the emperor’s well-being, as emphasized by his invocation of the Augustan Asclepius bolstered by the Augustan Heaven.

Many monuments to Asclepius were private. At Ilosva in Dacia, the cavalry prefect Caius Iulius Atianus invoked Aesculapius and Hygieia for ‘restoration’ (ob restitutionem, of his health, we presume).198 Publius Catius Sabinus, tribune of Legion XIII Gemina in Apulum, fulfilled his vow to a pantheon that included not only Aesculapius, Health, Diana, Apollo and Hercules (gods with strong healing associations), but also the military Lares and Penates (both are protective spirits), as well as the Lar (protector) of the road, Neptune, Fortuna Redux, Good Will and Hope.199 In anticipation of travel (perhaps a reassignment, soldiers rarely returned home after their tours of duty), Sabinus was taking no chances, and he sought the good will of deities with various overlapping functions, including health, safety and travel both on land and water.

In military contexts, we also see evidence of communication between gods and their patients, an essential factor of Asclepius’ incubation cult. The centurion Flavius Marcianus, attached to both Legion XIII Gemina and Legion XV Apollonaris, placed an altar to the Sun, Aesculapius and Hygieia on ‘their orders’ (iussu eorum).200 Veturius Marcianus, a veteran of Legion XIII Gemina, received a dream from the numen of Aesculapius, instructing him to worship Jupiter Dolichenus for the health of himself and his family.201 Interestingly, the dream came not from the god himself but instead from his divine spirit (numen), which in turn recommended supplicating yet another deity. Assigned to Dacia in AD 106, the legion was not relocated until 271. Thus the dating of the stone is uncertain. Merlat suggests that Dolichenus’ primacy on the dedication underscores his own healing function. Like Asclepius, Baal of Doliche (Jupiter Dolichenus) may also have overseen temple healing.202 Asclepius’ numen seems to suggest that Marcianus seek help from a god whose sphere of authority (Syria) is physically closer to Dacia or whom Asclepius may deem as less busy -Asclepius’ untimely absence from his own temples occasionally inconvenienced his worshippers, who staunchly criticized the god for his ‘multi-locality’.203

Temple healing and cures by dreams were not restricted to Asclepius. Substantial deposits of small terracotta ex-votos representing body parts (as in the Asclepius cult) point to a robust tradition of temple healing in central Italy from the fourth century BC onwards.204 Additional evidence comes from non-Roman traditions, both localized cults and widespread Eastern rites promulgated by Roman soldiers and merchants. In response to a vision or dream (ex viso), Atilius Primus, a centurion stationed at Carnuntum in Pannonia Superior, made a dedication to Jupiter Dolichenus for his health.205 The freedman Quintus Antistius Agathopus (a Greek cognomen) erected an altar to the genius of the imperial house for the health of his patron, legate of Legion II Adiutrix, and his family.206 Agathopus’ entreaty is repeated four times, a magical strategy intended to increase the strength of the request.

Temple healing is also suggested in Romano-Celtic contexts. At the river Severn in Lydney Park, the syncretized Mars Nodens was honoured with an extensive temple complex that included shrines, a bath suite, courtyard house and narrow building with numerous cubicles, probably the abaton, where Nodens would effect cures on his sleeping worshippers.207 Small offerings further suggest a healing cult: among these are pins of various materials,208 objects representing the sun and water,209 and bronze and stone dogs. Also linked with Asclepius, dogs were thought to heal wounds by licking them, and dog bones, together with other votives, were found in wells (associated with healing cults in Romano-Gaulish contexts).210 Nodens was cultivated by soldiers stationed near Lydney Park, including a naval officer in charge of the fleet’s supply depot, Titus Flavius Senilis, who may have made a pilgrimage to the site for his health.211

Healing cults are associated with water (springs, rivers and wells). Both cold and hot springs had long been used for their curative properties to treat many ailments.212 In Vitruvius, we find descriptions of the medicinal properties of different types of hot springs (sulphurous, aluminous, bituminous, alkaline).213 In Pliny, Celsus and others, we read instructions for thermo-mineral healing of various complaints: dislocations, fractures, gout, foot conditions, headaches, psoriasis, diseases of the eyes and the ears and mental illness.214 Pliny especially recommends the sulphurous springs at Aquae Albulae, between Rome and Tivoli, for treating wounds.215 Patients took their cures both by soaking/swimming or imbibing – thermomineral water was prescribed to relieve internal pain and bladder stones.216 With their expansion, the Romans quickly appropriated many of the curative springs in Western Europe for medicinal and recreative use. Interestingly, under Hadrian, spas were reserved exclusively for the ill during the morning hours.217

Hot springs were dedicated to a variety of gods with healing associations: Apollo and Diana, Aesculapius and Hygieia, Jupiter, Vulcan, Mars, Minerva, Venus, Dionysus, Silvanus and others.218 Pre-eminent among such deities was Hercules, who presided over thermal springs at Thermopylae, as well as spas in Italy, Sicily and Dacia.219 Priests and physicians attended the sick at the Fontes Sequanae, where dwelled the water spirit who personified the River Seine, and at Bath (Aquae Sulis), where Sulis Minerva presided over a hot spring and healing sanctuary. Small finds there include ex voto body parts and an oculist’s collyrium stamp.220 Soldiers were sent to spas for cures and convalescence or rest and recreation.221 The presence of the Roman Army encouraged the economic growth and prosperity of medicinal sites,222 but locals and soldiers occasionally came into conflict over spa sites, for example at Scaptopara in Thrace (ad 238), residents complained to Gordian III that many Roman officials, including soldiers, would descend upon the hot springs and demand lodging and other services without payment.223 In the early second century AD, Legion IX Hispania came to Aachen (Aquae Granni) to recuperate, for which convalescence its prefect and senior centurion (primus pilus) Latinius Macer, a native of Verona, dedicated an altar in fulfilment of his vow to Apollo (syncretized with the local patron of the springs – again human health connects with the land through its divine patron).224 The altar shows an enthroned Apollo holding his lyre and with a quiver on his right shoulder (see Figure 5.8).

Baden (Aquae Helveticae), near the legionary headquarters for Legion VIII Augusta (Vindonissa), was the site of a military hospital and a healing spa to Mercury.225 Water from the hot springs was piped to therapeutic basins, one of which could accommodate nearly 100 bathers.

In both civilian and military contexts, healing also straddled the supernatural.226 Even the word medicus, which usually means ‘healer’, is used in magical contexts: Silius Italicus qualifies the snake charming Marmaridae, whose spells obviate serpent venom, as a ‘medical people’ (medicum vulgus).227 Because of his successful medical practice, many of Galen’s jealous rivals accused him of prognosticating cures by divination, dreams, astrology or sacrifices – slurs which injured Galen’s delicate ego.228 Despite his dismissal of magical cures, Galen nonetheless preserves many cures that employ ‘magical’ ingredients or ritual methods (such as plucking medicinals with the left hand before sunrise, or a paste of earthworms, pepper and vinegar to cure headaches).229 Medicinal charms, chants and amulets, furthermore, were common, even in the arsenal of professional healers. In Homer, the sons of Autolycus used charms to heal Odysseus’ boar wound.230 Theophrastus handed down a chant to cure sciatica,231 while Cato preserved one for setting dislocated limbs,232 Marcus Varro had an incantation for gout233 and Caesar would recite a prayer for safety before travelling.234

Figure 5 8: Apollo Grannus at Baden: AE 1968: 323. (http://www.wasserkalender.de/)

Pliny asserts that there is no one who ‘does not fear being cursed by dreadful invocations’, and many owned amulets to shield themselves from ‘all forms of harm and danger’,235 such as Sulla, who reputedly wore an amulet into battle.236 Although Galen generally dismisses amulets as within the sphere of superstition, he prescribes green jasper amulets (both inscribed and uninscribed) for stomach ailments.237 He explains the efficacy of peony root charms in epilepsy patients according to the tenets of the atomic theory: patients would inhale small particles from the peony root, which in turn staved off the attacks.238 There is no shortage of amulets recovered from Roman imperial military sites, many of which were likely worn by soldiers to protect them from injury or malice. At Camulodunum (Colchester), for example, four bone fist and phallic pendants, intended to enhance the wearer’s virility or potency, may have belonged to soldiers. The phallus, an obvious symbol of fertility, was also a powerful apotropaic (offering protection against evil) device, adorning gardens, walls, pottery and jewellery (see Figure 5.9).239

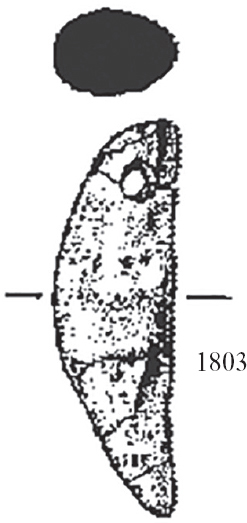

A pierced dog’s canine was excavated from a grave deposit at the same site (see Figure 5.10).240 Like the phallus, the hound’s tooth may have been thought to confer strength or protection, but the dog, especially in Celtic areas, was a healing animal.

Figure 5.9: Bone fist and phallic pendants at Colchester. (Image taken from: Crummy (1983), nos 4255, 4258, 4259)

Figure 5.10: Pierced dog’s canine at Colchester. (Image taken from Crummy (1983), no. 1803)

Conclusion

In these pages we have investigated the complex, multifaceted, synergistic and sometimes contradictory threads by which a Roman of the imperial era (soldier or civilian) might seek medical care. Although the evidence for an established, administratively regulated military medical corps seems to raise as many questions as it answers, we can be sure that some mechanism, whether formal or AD hoc, existed to ensure the health of the Roman soldier. Military physicians, many of whom were Greek by background or training, adhered to the heuristic models of treatment of illness and injury as dictated by Roman authorities. No doubt a network of military bases facilitated the swift transmission of medical practice and theory.241 The military healthcare system was efficient, cutting-edge and (sometimes) free to enlisted soldiers. Curative drugs, bandages and foodstuffs were distributed to military bases throughout the Empire. There were criteria for selecting the most able-bodied recruits, those men who were likely to be strong and healthy enough to endure the physical demands of life on the march. There were also guidelines for ensuring health in temporary and permanent camps, principles corroborated in the archaeological record. Concern for the soldier’s health is manifested in regimen and training, diet, salutary camp surroundings and state-of-the-art hospital facilities, especially at larger legionary bases.

Military physicians and imperial soldiers, nonetheless, availed themselves of many approaches to their health, including magical chants, apotropaic amulets, curative waters, incubation and prayer. Although (Greek) humoral theory was largely rejected by the Romans in favour of mechanistic (rational, empirical) models of the human body, alternative medicine was embraced in conjunction with state-sponsored ‘rational’ medicine. In order to maintain or restore health, local and Roman state gods were entreated for the health and well-being of units, legions and individual men. Some soldiers (including generals) hedged their bets with apotropaic amulets which were thought to avert evil and protect the wearer. The cults of healing deities flourished in many contexts well into the third century ad. Neither ‘rational’ nor ‘divine’ healing was pursued in isolation. Even during the Roman imperial era, health depended as much on the individual as on external factors, including divine favour and the health/success of the state and its leaders.

Notes

1. Israelowich (2015), pp.87–88.

2. Wedlake (1982); Irby-Massie (1999), pp.143–44.

3. Hdt. 7.114, 2.181; see also Plut. Dion 14.

4. Cic. Nat. Deor. 3.33.81; Lucr. 4.638; Virg. Aen. 4.514; Livy 40.24.5.

5. Especially Mart. Ep. 1.47, 5.9.

6. Pliny Nat. Hist. 29.14.

7. Pliny Nat. Hist. preface 14; see Naas (2002), pp.16–34; Doody (2009).

8. For more on the Roman encyclopedic tradition, see Oikonomopoulou (2016), p.973.

9. Davies (1969), p.85; Nutton (1969), p.265; Salazar (2000), p.79; Israelowich (2015), pp.87–88, 107–08. The Spartan Archagathus, the first physician on the public payroll at Rome, was a ‘wound surgeon’ (vulnerarius medicus): Pliny Nat. Hist. 29.13; Nutton (1981), pp.17–18. To be sure, not all physicians, much less those attached to the Roman Army, would have been ethnically Greek. Tiberius Martius Castrensis, a medicus stationed in Aquincum (Budapest, Pannonia Inferior: CIL 13.1833) in AD 147, may have been Celtic.

10. Veg. Mil. 1.3.

11. P. Oxy. 39; Davies (1969), p.92; Davies (1970b), p.99.

12. Veg. Mil. 3.2. Roman legend exalts farming and country-life: from the shepherd boys who founded the city to Cincinnatus at his plough when a senatorial delegation recalled the retired statesman to service and who returned to his fields after his first dictatorship (Livy 3.26, 3.29). Only the landed were permitted to fight in the army – until the Marian reforms of the early first century BC, when the promise of land grants to retiring soldiers was a powerful recruiting incentive – Sall. Jug. 85; Santangelo (2016), pp.33–36; cf. Brunt (1962). Senatorial alliances were struck and broken in efforts to secure these land grants. Pompey’s boon for his participation in the so-called First Triumvirate was land for his veterans, by which he assured their loyalty. See also Irby (2015), pp.257–60.

13. Although recommending moderate exercise, Galen was highly critical of excessive, competitive athletics: Medical Collections 6.21–36, CMG 6.1.1.177–87; Protrepticus 11 (1.29 Kuhn); see Konig (2005), pp.280–281. In AD 128, Hadrian reviewed the troops at Lambaesis at their exercises, executed with brutal Roman efficiency. In his detailed address, Hadrian described many drills, including javelin tossing, wall building and cavalry charges. He admonished those who performed poorly and praised those whose exercises ‘had the appearance of actual combat’. His speech is poorly preserved in a fragmentary monumental inscription: CIL 8.18042.

14. Vegetius asserts that men from cold climates have an overabundance of blood, but they lack intelligence – a condition not conducive to camp discipline. Those from warmer regions have more intelligence, but their paucity of blood renders them afraid of receiving wounds, thus making them poor soldiers – Veg. Mil. 1.2; see further Arist. Pol. 1327b; Irby (2015).

15. Arist. Pol. 1327b; Vitr. Arch. 6.1; Strabo 6.4.1.

16. Vitr. Arch. 6.1.2.

17. Davies (1970b), p.85; Scarborough (1981).

18. Davies (1970b), p.98.

19. This designation evokes the ancient Italic peoples’ renown for curing serpent bites with their bodies, like the Psylloi of North Africa: Pliny Nat. Hist. 7.14; Nutton (1985); Jones-Lewis (2016), p.411; cf. Hor. Epod. 17.30.

20. Davies (1969); Davies (1970b), pp.86–87.

21. Hdt. 2.84, 3.1.1, on Egyptian ocularii; for eye salve recipes: Celsus Med. 6.6; Pliny Nat. Hist. 21.138. Celsus also provides a detailed description of cataract surgery: Med. 6.14. For oil lamps and eye disorders, Donahue (2016), p.613.

22. Spiral 6d; Rossi (1971), p.152; Manjo (1975), p.390.

23. Grmek (1983); Nikita, Lagia & Triantaphyllou (2016), p.466.

24. D’Amato (2016), p.804. Cf. Salazar (2000), p.20.

25. Haesit enim sub gutture vulnus et udae vocis iter tenuemque inclusit sanguine vitam: Virg. Aen. 7.532–34; cf. Luc. 3.582–91 where a naval officer suffers from a similar double-wound to both his back and chest. All translations are by the author.

26. Virg.Aen. 12.374–82.

27. Virg.Aen. 11.692–93.

28. Virg. Aen. 11.816–17.

29. Virg.Aen. 11.698.

30. Sil. Ital. Pun. 5.447–56.

31. Luc. 9.764–82. For the seps, Nikander Ther. 145–56.

32. Wick (2004), p.279; Desclos & Fontenbaugh (2011), p.203.

33. For the neurological effects of envenoming bites, Harris & Goonetilleke (2004).

34. Galen de Atra Bile (5.160K).

35. Caes. Afr. 88. Cf. Ovid Metam. 7.849.

36. Luc. 7.566–67.

37. Sil. Ital. Pun. 6.68–69.

38. Tac. Ann. 1.71.

39. Tac. Ann. 1.69.

40. Dio 68.8.2.

41. Livy 23.36.4, 23.44.5, 40.33.1; see also Tac. Agr. 38.1, Germ. 6.6.

42. Livy 30.34.11; Dion. Hal. Rom. Ant. 8.65.

43. Caes. Afr. 21; see also Caes. Civ. 3.75.

44. Tac. Hist. 2.45.

45. Caes. Gall. 3.4.4.

46. Caes. Gall. 5.40.5.

47. Caes. Civ. 3.75.1.

48. Onasander Strat. 1.13–14; Caecina lost all of his baggage including medical supplies in the marshes of the Ems in AD 15: Tac. Ann. 1.65.

49. Celsus Med. 7.5; Paul of Aegina 6.87; Davies (1970b), p.89; see also Salazar (2000), pp.47–50.

50. Galen On Anatomical Procedures 2.83–84 (2.394–95K).

51. Rufus Medical Questions 51.

52. Virg. Aen 10.486, 11.816.

53. Amm. Marc. 18.8.11; see also Aen. Tac. 31.16. In the chaos of battle, Ammianus fails to report if he was successful.

54. Paul of Aegina 6.88.3; Bliquez (2015), p.143.

55. On the dangers of cutting into blood vessels or sinews, Celsus Med. 2.10.15.

56. Salazar (2000), pp.18–20.

57. Pliny Nat. Hist. 16.159.

58. Paul of Aegina 6.88.2.

59. Dio 36.5.

60. Salazar (2000), p.19.

61. A bivalve speculum with open valves would indeed resemble an upper case upsilon (Y). Specula were commonly used in obstetrics and proctology, but Celsus cites this instrument only in the context of missile removal. In Celsus we have the first (extant) literary reference to the bivalve speculum. Several specula survive at Pompeii, including one quadrivalve, two trivalve and two small bivalves: Bliquez (2015), p.54.

62. Rufus 51. For a surgeon who missed part of the shaft in a man hit by a blow from a catapult, Hippocr. Epid. 5.95. The patient died in three days. Projectiles frequently broke on impact to prevent re-use (Amm. Marc. 31.15.11) or to complicate the extraction of the tips (Paul of Aegina 6.88.2).

63. Pompeii, House of Siricus, National Archeological Museum of Naples, inv. 9009.

64. Virg. Aen. 12.400–04.

65. For dittany, Theophr. Hist. Plant. 9.16; Pliny Nat. Hist. 26.142. For self-medicating goats, Cic. Nat. Deor. 2.126, following Arist. Hist. An. 9.6.1. Dioscorides (3.32) compares dittany with pennyroyal (3.31), prescribing both as abortifacients, for which purpose dittany can either be ingested or applied topically.

66. Salazar (2000), p.49; Bliquez (2015), pp.141–43. An instrument fitting this description, found in Asia Minor, has proven to be spurious, but is perhaps a copy of an authentic ‘spoon of Diocles’: see further Künzl (1991), pp.26–27; Krause (2009), pp.71–72.

67. See also Celsus Med. 7.12.1A.

68. Celsus Med. 5.26.21–24; Davies (1970b), p.89; Salazar (2000), pp.9–38.

69. Baker (2004), p.140, for ear probes; see appendices 4–10 for medical instrument finds. Baker lists twenty-one ear probes in her catalogue of eighty-four remains from Neuss alone.

70. Salazar (2000), pp.28–30. For a general discussion, Mayor (2003).

71. Scribonius Largus 176: also good for treating bites from rabid dogs.

72. Galen Ad Pisonem de Theriaca 10 (14.244–45K); Paul of Aegina 6.88.4.

73. Sil. Ital. Pun. 1.322, 3.272–73. That the Celts used arrow poison – (Arist.) Mir. Ausc. 86 – is confirmed neither in Caesar or Strabo.

74. Rufus Medical Questions 50–55.

75. Celsus Med. 5.27.

76. Paul of Aegina 6.88.4.

77. Galen (ibid.) and Paul of Aegina (ibid.). According to Pliny Nat. Hist. 25.61, the Gauls dipped their hunting arrows in hellebore.

78. Luc. 9.614.

79. The ingredients of many medicinals used in antiquity are chemically similar to their modern counterparts: henbane yields hyoscyamine, a tropane alkaloid, still an ingredient in medications for gastro-intestinal disorders, kidney stones and gallstones. St John’s Wort remains a popular treatment for many complaints: Davies (1970a); Davies (1970b), p.91.

80. Achilles’ woundwort, for example, which also closes ‘bleeding wounds’ and relieves inflammation: Dioscorides 4.36.

81. Especially effective, according to Dioscorides, are verdigris, 5.79.9; pine tree leaves, 1.69.2; pimpernel (Anagallis arvensis L.), ‘good for wounds’ and for removing splinters, 2.178.1. Pliny Nat. Hist. 23.8 specified the cooling and astringent fruit of oenanthe, the wild grapevine, both fresh and dried, as a plaster for bleeding wounds.

82. Frankincense, 1.68.2; woad (Isatis tinctoria L.), also an anti-inflammatory, 2.184, 185; comfrey (Symphytum bolbosum L.), 4.10.2; aloe (Aloe vera L.), 3.22.2; Pliny Nat. Hist. 27.18–19.

83. Murex snail, 2.4; cyclamen root (Cyclamen graecum Link) boiled in old olive oil, 2.164.3; vervain (Lycopus europaeus L.) with honey, 4.59; burnt copper, 5.76.3.

84. Pliny Nat. Hist. 25.67; Dioscorides 3.6; Nutton (2013), p.181, calls centaury ‘a true panacea’.

85. Dioscorides 1.102. Pliny Nat. Hist. 12.77 recommends the exotic enhaemon, an Arabian ‘olive’, as particularly effective at closing wounds.

86. Chaste tree (Vitex Agnus-castus L.), Dioscorides 1.103.3; opium poppy (Papaver somniferum L.), Dioscorides 4.64.4; rosemary (Rosemarinus officinalis L.), Pliny Nat. Hist. 24.99, gums, Nat. Hist. 24.106; lycium (Dyer’s buckthorn, Rhamnus petiolaris), Nat. Hist. 24.126; hyoseris (Cichorieae Hyoseris L.), Nat. Hist. 27.90; and poterion, Nat. Hist. 27.123. Hyoseris and poterion are not cited in Dioscorides. Poterion is known only in Pliny, perhaps tragacanth (Astragallus gummifer Labill.), according to LSJ (sv poterion).

87. Scribonius Largus 201–20. Isis plaster, 206.

88. Scribonius Largus 208.

89. Camden (1806), 3.470; Davies (1970b), p.93.

90. Davies (1970b), p.93.

91. Knorzer (1970); Davies (1970b), p.91.

92. Watermann (1974), pp.167–72; Nutton (2013), pp.182–83.

93. Davies (1970b), pp.92–93.

94. Davies (1970b), p.101; Jackson (1990), p.34; Nutton (2013), p.184.

95. Celsus Med. 2.18.1–13; Davies (1970a), p.102; Davies (1970b), pp.91, 99. Celsus recommends figs for coughs and abscesses (Med. 4.10.1; 5.5, 11, 12, 14, 28). In Pliny, fig juice is an antidote to stings from scorpions and insects; its leaves function as an antidote to rabies, Nat. Hist. 23.117–30.

96. Pliny Nat. Hist. 23.94; PSI683; P. Mich. 481 – Youtie & Winter (1951); Davies (1970a), p.104.

97. Celsus Med. 5.26.23B.

98. Galen Medical Methods 5 10.320K.

99. Dioscorides 2.4, 2.164.3, 4.59, 5.76.3.

100. Berlin F2278.

101. CIL 13.11979, an altar to the genius of the imperial house dedicated by Titus Flavius Processus, a medicus ordinarius, whose unit is not preserved.

102. ILS 9095: Legion XIV Gemina.

103. RIU 3.680.

104. CIL 8.2553.

105. Dion. Hal. Rom. Ant. 9.50.

106. Celsus Med. 26.24.

107. Galen On Bandages 18A.774–775K; Oribasius Coll. Med. 48.27.

108. Salazar (2000), pp.50–53.

109. Scarborough (1968), p.255. Plutarch omits mention of medical staff in his account of Crassus’ disaster at Carrhae (Crass. 24–25).

110. Plut. Mar. 6.3, Caes. 34.3, Pomp. 2.5–6. Later, emperors would travel with private physicians.

111. Cic. Tusc. 2.16.38: at vero ille exercitatus et vetus ob eamque rem fortior, medicum modo requirens a quo obligetur.

112. See Scarborough (1968), p.256. Elsewhere in Cicero, medicus refers to a healing doctor: Fam. 16.9; Salazar (2000), p.78.

113. Veg. Mil. 2.10; Dig. 50.6.7.

114. Scarborough (1968), p.257.

115. Suet. Caes. 42. See Baader (1971), p. 17, & André (1987), pp.86–89, for possible ulterior motives.

116. Wilmanns (1995a) contends that organized military healthcare was established during Augustus’ reign.

117. Vell. Pat. 2.114.1–3; Davies (1970b), p.98; Nutton (1986), pp.37–38.

118. Am. Marc. 18.2.9, 15; see Salazar (2000), p.83.

119. Suet. Aug. 59; Dig. 27.1.6.8; Dio 53.30. See also Manjo (1975), p.390; Jackson (1993), p.83. For ranks and pay grades, Davies (1969); Davies (1970b), pp.86–87; Davies (1972).

120. Ael. Tact. 248 (Köchly); Dig. 50.6.7. On the military oath: Brand (1968), pp.91–98.

121. Nutton (1969), p.262.

122. Galen To Postumus 14.649–650K.

123. Davies (1969); Davies (1972). For collections of the epigraphic evidence, Briau (1866); Grummerus (1932); Heidenreich (2013), pp.275–384.

124. Dioscorides: stratioikon ton bion: praef. 4; Davies (1970b), p.88; Nutton (2013), p.182.

125. Riddle (1985), p.4; Scarborough, in Beck (2005), p.xvi.

126. Scribonius Largus 163; Nutton (2013), p.175; CIL 3.12116 for a governor’s private physician.

127. FGrH 2b.200; Scarborough (1981); cf. Davies (1970b), p.88.

128. Galen de Compositione Medicamentorum 2.13 (12.557K).

129. Pliny Nat. Hist. 25.20–21; Davies (1970b), p.92.

130. Celsus Med. 5.26.21–24; Davies (1970a), p.104.

131. Celsus Med. praef. 43

132. CIL 8.2553; Nutton (1969), p.265; Davies (1970b), p.86; Salazar (2000), p.80.

133. CIL 7.690 (RIB 1618); Callies (1968), p.24; Rossi (1987), p.282; Salazar (2000), p.81.

134. SHA Aurel. 7.8.

135. Caes. Civ. 3.78.1; see also Manjo (1975), p.382. Livy (10.35.7) tells us that, during the Samnite War (294 BC), the groans of wounded and dying soldiers demoralized the healthy soldiers.

136. In 480 BC, the consul Marcus Fabius called upon the patricians to look after troops wounded in the Etruscan wars; his own family took in the largest number and attended to them diligently (Livy 2.47.12); cf. SHA Alex. Sev. 47.

137. Baker (2002), p.70. E.g., SHA Hadr. 10.3, where Hadrian visits sick soldiers in hospitiis (their barracks, not necessarily military hospitals). Alexander Severus visited his sick soldiers in their tents (per tentoria), not in the valetudinarium: SHA Alex. Sev. 47.2. This suggests either barracks or perhaps a multi-tent MASH unit.

138. Hyginus Gromaticus (late first or early second century AD) de munitionibus castrorum 4. The standard bearer Domitius was able to maintain quiet for troops convalescing on the Egyptian coast by relaying signals visually, instead of audibly, thus maintaining the quiet in the vicinity of the recuperating men: PSI 1307 col 2.20; Davies (1970b), p.100.

139. Valetudinarium is specified on stones from Moesia Superior (CIL 3.14537 [ILS 9147]) and Aleppo (AE 1987: 952). Personnel in charge of hospitals (optiones valetudinarii) are also recorded at Lambaesis (CIL 8.2553, 2563), Bonn (CIL 13.8099) and in Italy (CIL 6.175).

140. This architectural standardization suggests an organized and centralized medical corps: Nutton (1969), pp.262–63. For a critical discussion of archaeological and artefactual remains, Baker (2002).

141. Nutton (1969), p.266; Salazar (2000), p.78. The tents for the wounded in Livy 8.36.1–8 may not reflect the accommodations made in the fourth century BC, but rather those of Livy’s own day.

142. Salazar (2000), pp.81–82. For operating rooms, Schultze (1934), who took hearths in a room behind a large entrance hall as intended to sterilize instruments. Literary sources do not support the existence of dedicated operating rooms, nor was there any concept in Greco-Roman medicine of ‘sterilization’. Salazar concedes the practicality of a centralized area for treating the wounded.

143. Bowman & Thomas (1991).

144. P Dura 95: aeger remansit.

145. P Dura 102: non sanus; Davies (1970b), p.101.

146. Food poisoning: Youtie & Winter (1951), no. 468; Jackson (1990), p.131; Davies (1970b), p.101. Scurvy: Pliny Nat. Hist. 25.20–21; Davies (1970b), p.105. Prosthetics: Nutton (2013), p.189; see Celsus Med. 7.16 on amputating limbs.

147. For post-traumatic stress disorder in antiquity, see Tritle (2000); Melchior (2011); van Lommel (2013).

148. Davies (1969), pp.93–94.

149. Edelstein & Edelstein (1998), pp.205–46.

150. Celsus Med. proem. 4.

151. Philippi, CIL 3.640; Rome, CIL 6.10133; Travi, CIL 11.1306.

152. CIL 8.18091. Jupiter is here cited together with Aesculapius and Silvanus Pegasianus. For Silvanus Pegasianus, see Dorcey (1992), p.64.

153. CIL 8.18007 (ILS 2625): Bescera, Numidia. For Mercury, see Caes. Gall. 6.17; Irby-Massie (2000). For Augustus-Augusta, see Fishwick (1987), pp.446, 448.

154. Legion II Adiutrix at Aquincum: CIL 3.3470 – ILS 2453; Heidenreich (2013), p.346.

155. Legion XXII Primigenia Pia Fidelis: CIL 13.6728 – Heidenreich (2013), p.155: Mogontiacum, Germania Superior. The dedication details Vercellis’ distinguished military career, including his service as the signifer and primus pilus. See also CIL 13.11815, erected by a centurion of the same legion to the Capitoline Triad and ‘all the other immortal gods’ in response to a dream.

156. In ancient Near Eastern cultures, the health of the community was closely tied to the health of the land and its environment: McCall in Irby, McCall & Radini (2016), pp.296–301.

157. CIL 13.6471; Heidenreich (2013), p.210: Bockingen, Upper Germany.

158. RIB 03.3253. For Hygieia in Africa: CIL 3.558, 7291, 7837. For Dolichenus in general, see Speidel (1978).

159. CCID 235.

160. CCID 154.

161. Speidel (1978), p.10; Irby-Massie (1999), p.63.

162. V Macedonia and XIII Gemina Gallieni: CIMRM 2.1592. For Mithras, see Beck (2006).

163. IDR 03–05-01.71; Apulum, Dacia Alba Iulia. For Epona, see Linduff (1979); Oaks (1986).

164. AE 1985: 751; Municipium Montanensium, Moesia Inferior.

165. CIL 3.12371; Moesia Inferior.

166. AE 1987: 942; Apollonia, Galatia.

167. CIL 3.7420.

168. AE 2009: 1760; Africa Proconsularis.

169. CIL 7.40 (RIB 143).

170. AE 1993: 1304; Matrica, Pannonia Inferior: a watch commander of Legion I Adiutrix for the health of all of his friends and family.

171. CIL 2.2634 (ILS 2299; CIMRM 804), Asturica Augusta, Hispania Citerior; Heidenreich (2013), p.351, Aquincum, Pannonia Inferior; CIL 5, 811 (CIMRM 01.743), Aquileia; CIL 7.41 (RIB 144), Aquae Sulis (Bath).

172. AE 1947: 33: Brigetio, Pannonia Superior, an altar erected by Rennius Candidus, a veteran of Legion I Adiutrix, and his wife Aurelia Marcellina.

173. CIL 8.2627: Lambaesis, Numidia, an altar erected by Gaius Iulius Valerianus, a centurion of Legion III Augusta on behalf of his own health, his wife’s, his brother Iulius Proculus, centurion of Legion V Macedonia, sister-in-law Varia Aquilina and niece Iulia Aquilina.

174. AE 1930: 32, Germania Inferior. Dis Infernis / Plutoni et Proser(pinae) / C(aius) Iul(ius) Agelaus / vet(eranus) leg(ionis) I M(inerviae) P(iae) F(idelis) / pro lumine suo / pro salute sua / et Meletenis v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens). In the singular (lumine), lumen refers to life, e.g., AE 1920, 25; BCTH 1953, 127 (both Africa Proconsularis, the latter with magical implications); CIL 2.3256; CIL 3.14190,1; CIL 06.27383.

175. Eur. Alc. 456; Lucian Menippus or the Descent into Hades 1. For Lucina, Cic. Nat. Deor. 1.68. See also Virg. Aen. 6.680, where souls are about to go to the light (ad lumen). ‘Light’ (lux, lucis) is the root of Lucina, the Roman goddess of childbirth.

176. Hippocr. Reg. 1.4.

177. Hom. Il. 1.34–52; Virg. Aen. 12.391–94.

178. Pliny Nat. Hist. 29.3.

179. Parker (1983), pp.234–56; Lloyd (2003), pp.12–13; Petridou (2016).

180. Gorrini (2005); Nutton (2013), p.105. On the advice of the Sibylline Books, the Asclepius cult was introduced to Rome, in response to a plague: Livy 4.25.3.

181. Edelstein & Edelstein (1998), 2.1–64.

182. Strabo 14.19, Pliny Nat. Hist. 29.2.2; Horstmanshoff (2004), pp.337–38.

183. Edelstein & Edelstein (1998).

184. Paus. 2.27; Hughes (2008); Melfi (2010); Petridou (2016).