![]()

The palms of Mammon have disowned

The gift of our complacency;

The bells of ages have intoned

Again their rhythmic irony;

And from the shadow, suddenly,

’Mid echoes of decrepit rage,

The seer of our necessity

Confronts a Tyrian heritage.

JOSEPH YOUNGWITZ2, of 610 East Sixth Street, Manhattan, was among the smallest and least elegant of the one million New Yorkers ready to welcome Theodore Roosevelt home on 18 June 1910. His savings as a messenger boy were insufficient to gain him admission to the reception area in Battery Park. But he had $2.75 to spend on a bunch of flowers, and vowed, somehow, to get them into his hero’s hand.

That task looked progressively more difficult as police formed a double cordon up Broadway and Fifth Avenue, holding back a crowd that began collecting at dawn and soon filled both sidewalks all the way north to Fifty-ninth Street. It was a warm, humid morning. Straw boaters undulated3 twenty deep, like water lilies amid a bobbing of froglike bowlers. Female hats were fewer, but women were in the majority on the jerry-built scaffolds, some three stories high, offering ROOSEVELT PARADE SEAT RENTALS.

At 7:304 A.M. the first of twenty-one cannon shots flashed and boomed from Fort Wadsworth, and the Kaiserin Auguste Victoria loomed out of the haze at the head of New York bay. She was escorted by a battleship, five destroyers, and a flotilla of smaller vessels. At once a small launch bearing representatives of the federal government put out from the presidential yacht Dolphin, determined to beat four cutters loaded with Mayor Gaynor’s official welcoming committee, Roosevelt family and friends, local politicians, and gentlemen of the press. They raced one another to where the great liner was mooring in quarantine.

![]()

WHEN ROOSEVELT, SITTING IN his stateroom, heard the cannonade, his wife noticed a curious mix of pain and pleasure on his face. “He was smiling5, but looking forward”—to what, Edith did not say.

Possibly he was struggling with feelings beyond the comprehension of anyone who had not been, for seven and a half years, President of the United States. The twenty-one guns, the great gray battleship with its men standing at quarters, the launch coming alongside to a shrill of whistles; the arrival on board of his former secretary of the navy, his former secretary of agriculture, and most familiar of all, in a gold-laced uniform, his former military aide, Archie Butt—it was difficult to think of them as anything but paraphernalia of an administration still in power.

Of course they were not: the two cabinet officers, George von Lengerke Meyer and James Wilson, simply symbolized continuity between old times and new, and Captain Butt was extracting, from the leg of his boot, some letters from President and Mrs. Taft. Yet Roosevelt could not help falling at once into the habit of treating them authoritatively—just as Archie was heard to say, when they all went on deck to see the cutters approach, “Will you kindly6 let the President pass?”

Edith was the first to spot another Archie, sixteen years old, blond and bone-thin, on the foremost boat, Manhattan. He stood with his younger brother, Quentin, and other family members, among whom could be discerned the natty figure of Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. Edith’s New England reserve cracked, and she looked as though she wanted to jump overboard. “Think—for the first7 time in nearly two years I have them all within reach!”

Bidding farewell to his fellow passengers, Roosevelt escorted her down a gangway to the Manhattan at 8:20. He wore a silk topper and black frock coat. Edith presented a trim, if matronly figure in dark blue and white. Kermit, panama-topped, followed with Alice in a plaid dress and Ethel, looking almost pretty in mushroom linen, clutching her little black dog. For the next hour they were mobbed by Roosevelts of all ages and relationships, while Nicholas Longworth (impeccably dressed as always, to compensate for his bald shortness) and Henry Cabot Lodge staged a miniature conference of the House and the Senate.

Roosevelt embraced his sisters8 “Bamie” and Corinne, the former now deaf as well as bent by arthritis, the latter ravaged by the suicide of her youngest son at Harvard. Ted presented9 his petite fiancée, Eleanor Butler Alexander. The latter had won quick family approval, since she shared four Mayflower ancestors with Edith, and was the only child of wealthy parents.

While the Colonel continued to kiss and hug and pump hands, his distant Democratic cousin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt10, stood apart. Tall and slender, he sported a straw boater, and kept close to his own Eleanor,* an aggressively shy young woman whose chin receded as far as his own protruded. Franklin was said to have political ambitions.

Another cannonade began as Roosevelt transferred alone to the reception steamer Androscoggin. It was to ferry him ashore, after a short foray by the official flotilla up the Hudson. He crowed with delight when he saw that the battleship leading the way was theSouth Carolina. Twin-turreted fore and aft, still so new that her paint seemed polished, she was the first American dreadnought, a proud symbol of his efforts to build a world-class navy.

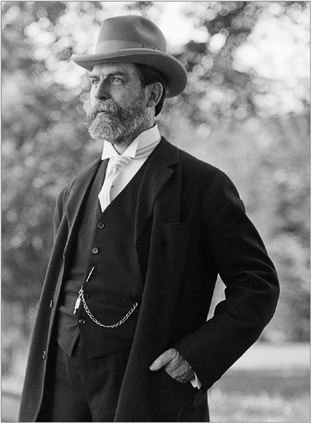

“THE NATTY FIGURE OF THEODORE ROOSEVELT, JR.”

Roosevelt’s eldest son at the time of his engagement to Eleanor Butler Alexander. (photo credit i4.1)

Roosevelt could not resist climbing out onto the Androscoggin’s bridge and standing there for a while, feeling himself the center of a vast marine movement churning north. Ahead to port and starboard, the warships (grimly gray now, not white as they had been in his day) guarded him. Behind came the cutters, flanked by a growing armada of private vessels and sightseeing boats. Well-wishers clustered on both New York and New Jersey piers. The air shrilled with steam whistles.

At Fourteenth Street the flotilla swiveled south. On the way back downriver, the Colonel shook the hands of the eminent New Yorkers who had arranged and paid for his homecoming. Most of them were greeted with his famous memory flashes. “My deadly rivals!” he joked at the sight of the editors of Munsey’s and Everybody’s magazines. And, “Hello, here’s my original discoverer!”11 to Joseph Murray, who had put him forward as a candidate for the New York State Assembly in 1881. Even when the recognition was obviously faked, his grin and vigorous squeeze exuded friendliness.

He was, in short, already politicking, bent upon charming as many people as he could see—even the black cook making him breakfast. Yet in the midst of his effusions, Roosevelt the writer could not resist secluding himself with the latest issue of12 The Outlook, to see how a story he had dispatched from Europe looked in print.

When, at last, he stepped onto the soil of his native city, a huge shout went up from the crowd waiting in Battery Park and ran echoing up Broadway. It built into such a roar that for the first time in his life he was brought to public tears. He had to turn13 toward the pilothouse and polish his spectacles before proceeding.

![]()

TO THE CHAGRIN of three thousand ticket holders in the park, Mayor Gaynor’s welcoming speech and Roosevelt’s reply were so brief that the parade got under way at 11:30, almost an hour earlier than scheduled. Reporters were left to guess what, if anything, the Colonel had meant when he said, “I am ready14 and eager to do my part … in helping solve problems which must be solved.”

During his ensuing five-mile drive uptown, standing most of the way in the mayor’s open carriage, he was deluged in ticker tape and confetti, and subjected to ceaseless roars of “Teddy! Teddy!” A man with a megaphone bellowed, “Our next President!” to a crescendo of applause. The parade was almost as long as the marine file had been, with a vanguard of mounted police and bandsmen followed by Rough Riders prancing on sorrel horses. “I certainly love my boys,” Roosevelt yelled at them. Thirteen carriages of dignitaries trailed his own. Then came another band, a marching mass of Spanish War veterans, two more bands, and finally more mounted police, guarding against incursions from the rear. The heat by now was tremendous, and he glistened with sweat as he waved his topper at the never-thinning crowd.

Archie Butt and William Loeb, collector of the Port of New York, rode in the carriage just behind him. Loeb had been Roosevelt’s private secretary in the White House, and agreed with Butt that there was “something different” about their former boss. So, for that matter, did Lodge and Nick Longworth. Butt was best able to express their collective thoughts:

[We] figured it15 out to be simply an enlarged personality. To me he had ceased to be an American, but had become a world citizen.… He is bigger, broader, capable of greater good or greater evil, I don’t know which, than when he left; and he is in splendid health and has a long time to live.

Just above Franklin16 Street, a small boy broke out from the curb, screaming, “Hey, Teddy! I want to shake hands with you!” The Colonel reached down and they managed a quick clasp, then police hustled the boy away.

“ ‘HEY, TEDDY! I WANT TO SHAKE HANDS WITH YOU!’ ”

Joseph Youngwitz presents a bouquet to his hero, 18 June 1910. (photo credit i4.2)

The parade thumped on up Broadway and Fifth Avenue. About an hour later, as it approached its end at Grand Army Plaza, the same urchin—who evidently knew how to ride subways—reappeared, this time waving flowers. Roosevelt took the cluster and called out, as police again swooped, “I think I have seen you before.”

Joseph Youngwitz confirmed to a reporter that this was true. He had shaken hands with his hero on a presidential visit to New York “about five years ago.”17

![]()

THAT EVENING18 ROOSEVELT sat in a rocking chair on the veranda of Sagamore Hill, watching the sun set over Long Island Sound. The day that had begun so loudly, with cannon booms and the most sustained shouts of adulation ever to assault his ears, was ending in quiet bird music. A storm during the afternoon had rinsed the air clean. From the belt of forest at the foot of his sloping lawn came the sleepy sound of wood thrushes chanting their vespers. Overhead in a weeping elm, an oriole alternately sang and scolded. Vireos and tanagers warbled. When dark came on, he heard the flight song of an ovenbird.

As a boy he had sat here when there was no house and no trees, only a grassy hilltop sloping down to Oyster Bay and Cold Sping Harbor. He and his first wife19 had planned to build their summer place on it. Death parted them before the foundation stone was laid. Being a young widower20 had not stopped Roosevelt from completing the full three-story, seven-bedroom structure before Edith arrived in the spring of 1887, already pregnant with Ted. Here, presumably, he would welcome his first grandchild. And here, probably, he would die.

“One thing21 I want now is privacy,” he told a New York Times reporter. “I want to close up like a native oyster.” Only two public functions threatened: Ted’s wedding in a couple of days’ time, and a Harvard visit at the end of the month. Beyond them, all of July lay free. He could settle at his desk in the library, and pursue his new career as contributing editor of The Outlook. He had taken a vow of political silence22 for two months.

During the next23 twenty-four hours he either heard or saw forty-two species of birds. This beat by one the total that Sir Edward Grey had been able to identify in the New Forest. From the point of view of melody, there was no contest at all. When he strolled around the house, or jogged down the hill to bathe, his ears rang with the calls of thrashers in the hedgerows and herons in the salt marsh, the hot-weather song of indigo buntings and thistle finches, the bubbling music of bobolinks, the mew and squeal of catbirds, the piercing cadence of the meadowlark, the high scream of red-tail hawks.

All of them were listed in the catalog, Notes on Some of the Birds of Oyster Bay24, Long Island. He had no need to consult that authoritative work, having written and published it himself, at age twenty.

![]()

OVER THE WEEKEND25, newspaper editorials generally agreed that Theodore Roosevelt stood at the peak of his renown. To the Pittsburgh Leader, the welcome extended him by New Yorkers had approached “deification.” The New York Evening Post described it as “sobering” in its implications, but praised him for not taking political advantage of the moment. “Never before in the history of America,” commented the Colorado Springs Gazette, “has a private citizen possessed the power which Mr. Roosevelt now holds.” The Philadelphia North American held that he could win a third term as President in 1912, even if he ran as a Democrat. Few sympathies were extended to the man he had chosen to succeed him. “Never mind, Mr. Taft,” the Chicago Daily News jeered. “When you are an ex-President you can be a celebrity yourself.”

In trekking so many thousands of miles, so far from home, Roosevelt seemed to have been away a long time. Taft’s presidency felt almost over, as though the coming elections were to mark its twilight, rather than its meridian. In fact, Taft had been in the White House less than a year and a half, and was not averse to a second term. He enjoyed his job’s lavish perks, if not the work that came with them. But he had learned to minimize that. By nature an administrator, he saw no reason to initiate policy. The Constitution, as he read it, provided him unlimited time off for golf, free first-class travel, and the right to doze26 during meetings. He liked his $75,000 salary, and dreamed of being a justice of the Supreme Court after his prolonged sabbatical in the executive branch.

There was, besides, an all-powerful lobby determined to renominate him. While most of Manhattan had been brilliant with flags on the day of the Colonel’s great parade, Wall Street had remained defiantly drab. Bare poles projected from the House of Morgan, National City Bank, and the New York Stock Exchange. The austere men who ran these institutions were convinced27 that Roosevelt was insane: a politician so deficient in financial sense as to need medical treatment. At all costs he must be kept safely rusticated at Oyster Bay.

Roosevelt remained so close-mouthed that not even Henry Cabot Lodge, an early guest at Sagamore Hill, was able to divine his thoughts. But he had to make a quick decision which was bound to be interpreted politically: what to do about the President’s offer of hospitality. The letters Archie Butt28 had un-booted on the Kaiserin Auguste Victoria repeated the invitation three times. One was a copy of the long, querulous screed Roosevelt had already received in Britain. The second, addressing him as “My dear Theodore,” had been written while he was at sea, and the third, from Helen Taft, expressed the hope that Edith, too, would come to stay in the White House.

“I do not know29 that I have had harder luck than most presidents,” Taft’s cri de coeur read, “but I do know that thus far I have succeeded far less than have others. I have been conscientiously trying to carry out your policies but my method of doing so has not worked smoothly.” Page after page, the self-pity went on. “My year and two months [sic] have been heavier for me to bear because of Mrs. Taft’s condition.… I am glad to say she has not seemed to be bothered by the storm of abuse to which I have been subjected.… The Garfield-Pinchot Ballinger controversy has given me a great deal of pain and suffering.”

Taft even complained about being unable to lose weight.

Roosevelt had long been aware that the President lacked confidence. Uxorious and inordinately susceptible to guidance from his brothers Henry and Charles, Taft was always looking for approval. But this whining note was unbecoming for a chief executive. It did not augur well for the program of progressive reform he was supposed to have consolidated and extended. Taft took credit for30 “a real downward revision” of tariff rates, laws to improve labor safety and bolster postal savings, and a conservation bill giving the Department of the Interior increased powers of land withdrawal. But he wrote more convincingly about rising prices, opposition in Congress, and a hostile press. He thought there was a real possibility that the GOP would lose its House majority in the fall, and the White House in 1912.

In that case, Taft stated, Senators La Follette of Wisconsin, Cummins and Dolliver of Iowa, Bristow of Kansas, Clapp of Minnesota, Beveridge of Indiana, and Borah of Idaho—Midwestern insurgents to a man—would be responsible. “[They] have done31 all in their power to defeat us.” Whether by “us” the President meant himself and his administration, or himself and Roosevelt as a continuum, was unclear.

He mentioned32 in passing that it had been his idea to send the South Carolina to New York “and give you a salute from her batteries.”

Roosevelt sensed that he was being coerced. He replied on 20 June with a letter that began and ended affectionately, but contained one paragraph of startling coldness:

Now, my dear33 Mr. President, your invitation to the White House touches me greatly, and also what Mrs. Taft wrote Mrs. Roosevelt. But I don’t think it well for an ex-President to go to the White House, or indeed to go to Washington, except when he cannot help it. Sometime I shall have to go to Washington to look over some of the skins and skulls of the animals we collected in Africa, but I thought it would be wisest to do it when all of political Washington had left.

Having thus relegated Taft to a level of less consequence than zoological specimens, Roosevelt went with his family to attend the wedding of Ted and Eleanor in New York.*

![]()

TWO DAYS LATER34, emerging from the office of Charles Scribner’s Sons, on Fifth Avenue, he was mobbed by a crowd so overexcited that mounted policemen had to ride in and free him. “They wanted to carry me on their shoulders,” he told his sister Corinne. Gone was the frank adoration that had touched him during his parade. “It represented a certain hysterical quality that boded ill for my future. That type of crowd, feeling that kind of way, means that in a very short time they will be throwing rotten eggs at me.”

A dinner in his honor that night at Sherry’s, the most exclusive restaurant in the city, also failed to inspire him. The evening’s proceedings (printed on rag paper with illustrations hand-colored by Maxfield Parrish, bound in soft calfskin, and stamped with the Roosevelt crest) seemed to warrant a major statement. But his only reference to his future was cryptic, and disappointing to many guests. “I am like Peary35 at the North Pole,” he said, comparing himself to America’s other celebrity of the moment. “There is no way for me to travel but south.”

As soon as he returned home, political pilgrims began to make the three-mile trek from Oyster Bay station to Sagamore Hill. To President Taft’s alarm, they were all of the progressive persuasion. Gifford Pinchot arrived with James R. Garfield, a fellow conservationist who had served Roosevelt as secretary of the interior. Joseph Medill McCormick, the idealistic owner of the Chicago Tribune, came with Francis J. Heney, a Californian prosecutor famous for attacking corporate fraud. Booker T. Washington, Roosevelt’s former conduit to black Americans, wished to renew old ties. So did Senator Robert M. La Follette, although in this case the ties had never been strong. “Battling Bob” almost comically personified insurgency. His pompadour and soaring brow comprised fully half of his head, and a good deal of his height. “I am very much pleased36 with my visit to Colonel Roosevelt,” he announced.

Most of the pilgrims37 expressed similar pleasure. They were vague as to what, exactly, Roosevelt had said to them. Outsiders could only infer he was not praising William Howard Taft.

“He says he will38 keep silent for at least two months,” the President remarked, sulking over the morning newspapers. “I don’t care if he keeps silent forever.”

The most far-seeing commentary on Roosevelt in retreat came, ironically, from a blind Democrat, Senator Thomas P. Gore of Oklahoma.

Colonel Roosevelt is now39 in the most difficult and delicate positioning of his career. Has he the power to stand this greatest draft on his talent or his tact?… If he is to continue to progress, he must leave behind those whom he has created in his own image. If he does not now progress, he will be left behind by that great popular procession of which he delighted to imagine himself both the leader and the creator.

I trust that the progressives will have just cause to rejoice at his return and that the stand-patters will be compelled to bewail it as a catastrophe. I hope that enlightened, rational reform will find in Roosevelt the ablest reformer, otherwise there may be more of fiction than fact in this back-from-Elba talk, for, as I remember, the return from Elba was followed by the campaign of the Hundred Days, and the campaign of the Hundred Days was followed by Waterloo and a night without a dawn.

![]()

IN HIS REPETITIONS of the words progress and progressive, as well as Roosevelt and reform, Senator Gore showed much political acuity. If he had identified the Colonel’s followers more narrowly as Republican insurgents, he would have excluded forward-thinkers in his own party who found progressivism a realistic alternative to William Jennings Bryan’s sentimental “democracy of the heart.”40 Gore was, in effect, challenging Roosevelt to reform the Republican Party along “enlightened” lines. If its Old Guard leaders “stood pat” behind President Taft, then the “great popular procession” of progressivism might change avenues, and march behind a Democratic drummer.

Actually, the movement was not great in any statistical sense. To be progressive in 1910 was to belong to America’s middle class—only a fifth of the general populace41—and want to make bourgeois values the law of the land. To be insurgent was to belong to a much smaller, politically active minority, determined to write those values into Republican ideology. Roosevelt had been wary42 of the latter presumption since the fall of 1902, when La Follette and Albert B. Cummins, both Midwestern governors, emerged as pioneer insurgents. He happened to agree with some of their demands, such as regulation of railroad rates, but they had struck him as too parochial, uninterested in the other worlds that lay beyond their respective horizons of water and corn. He had done nothing to encourage the spread of further insurgencies through the central states during his first term, and little to welcome La Follette to Washington as a senator in 1906. Yet he had been pleased when reformers of both major parties praised his own “progressive” swing that same year. By 1908, the GOP insurgents had more or less ceded their cause to him.

Now it appeared that during his time out of the country, insurgent and progressive had become synonymous on orthodox Republican lips. Henry Cabot Lodge could barely force either obscenity through his reactionary whiskers. Roosevelt, describing himself as a “radical” at Oxford, meant, in the European sense, to convey that he was “a real—not a mock—democrat,” protective of the petite bourgeoisie like Clemenceau, liberal like Lloyd George. To Americans, the word unfortunately connotated grass roots.

Like many well-born men with a social conscience, Roosevelt liked to think that he empathized with the poor. He was democratic, in a detached, affable way. However, his rare exposures to squalor had been either voyeuristic, as when he encouraged Jacob Riis to show him “how the other half lived,” or vicarious, as when he recoiled from the “hideous human swine”43 in the works of Émile Zola.

Gifford Pinchot had the same kind of aristocratic fastidiousness. But most progressives looked down from a less exalted height. They felt threatened by the lower ranks of society. These were, in descending order, organized labor, represented by the AFL (trades-oriented, exclusionary, anti-immigrant), then the immense subpopulation of unskilled workers who toiled in factories and stockyards and mines, followed by poor whites, and at the dreg level, imported coolies, reservation Indians, and disenfranchised blacks.

Except for the two years he had lived with cowboys in North Dakota, and being the employer of a dozen or so servants, Roosevelt had never had to suffer any prolonged intimacy with the working class. From infancy, he had44 enjoyed the perquisites of money and social position. The money, through his own mismanagement, had often run short, and he was by no means wealthy even now, but he had always taken exclusivity for granted. The brownstone birthplace in Manhattan, the childhood tours of Europe, the open doors of Harvard and the Porcellian, the riverside ranch and hilltop estate, the gubernatorial mansion and the White House; Mrs. Astor’s balls, Brahmin clambakes, diplomatic banquets, and most recently, royal receptions; custom clothes, first-class sleepers, private boxes, pro bono lawyers, investment managers, club privileges, a driver and a valet—he had them all. Every night except Sunday he dressed in black tie for dinner, and when he rocked on the piazza, gazing out over his estate, he saw no other roofs, heard no street noise, breathed only the freshest air.

Ensconced, he lacked some of the neuroses of progressives—economic envy and race hatred especially. His radicalism45 was a matter of energy rather than urgency. It wanted to spread out and embrace social (not socialistic) reformers, labor leaders who spoke decent English, churchgoing farmers, businessmen with a sense of community responsibility, and even the occasional polite, self-made Negro, such as Booker T. Washington46. He had no attraction toward the Vanderbilts and the Rockefellers in their parvenu palaces. A strong sense of fairness saved him from complacency. If he was less motivated47 by compassion than anger at what he saw as the arrogance of capital, he chafed, nonetheless, to regulate it.

![]()

DURING ROOSEVELT’S ABSENCE48 OVERSEAS, a book by the political philosopher Herbert Croly had become the bible of the new social movement. Entitled The Promise of American Life, it was Hamiltonian in its insistence on the need for a strong central government, yet Jacksonian in calling for a war on unearned privilege—and it named Theodore Roosevelt as the only leader on the American scene capable of encompassing both aims. “An individuality such49 as his,” Croly wrote, “wrought with so much consistent purpose out of much variety of experience, brings with it an intellectual economy of its own and a sincere and useful sort of intellectual enlightenment.”

A close reading of The Promise showed that many of its ideas derived from Roosevelt’s Special Message50 of January 1908. More than any other utterance in his career, that bombshell had convinced Wall Street and the Old Guard that “Theodore the Sudden” was a dangerous man. The issues he raised then51—automatic compensation for job-related accidents, federal scrutiny of boardroom operations, value-based regulation of railroad rates, redress against punitive injunctions, strengthened antitrust laws—were the issues his followers wanted him to fight for now. The violent language he had used—“predatory wealth,” “purchased politician[s],” “combinations which are both noxious and legal”—had become commonplaces of progressive rhetoric. When insurgents called for a “moral regeneration of the business world,” and insisted that their “campaign against privilege” was “fundamentally an ethical movement,” they were shouting through a megaphone Roosevelt had left behind.

His own voice from those times echoed back to him:

The opponents52 of the measures we champion single out now one, and now another measure for especial attack, and speak as if the movement in which we are engaged was purely economic. It has a large economic side, but it is fundamentally an ethical movement. It is not a movement to be completed in one year, or two or three years; it is a movement which must be persevered in until the spirit which lies behind it sinks deep into the heart and the conscience of the whole people.

Sooner than he had predicted, and embarrassingly coincident with his return to America, the movement had begun to achieve critical mass, converging at state and local levels53. “Is this not54 the logical time,” the Kansas City Star asked in a front-page editorial, “to look forward to a new party which shall include progressive Democrats and Republicans—a party dedicated to the square deal and led by Theodore Roosevelt?”

The fact that55 a respected GOP organ could propose such a thing, along with “Roosevelt Clubs” springing up like wheat elsewhere in the plains states, explained why Taft’s Republican Congressional Campaign Committee was determined to suppress all insurgents running for state and federal offices in the fall of 1910. Roosevelt took no responsibility for the clubs. “I might be able56 to guide this movement,” he told Senator Lodge, “but I should be wholly unable to stop it, even if I were to try.”

![]()

ON 29 JUNE57, Theodore Roosevelt, A.B. magna cum laude, Harvard, ’80, returned to Cambridge for the thirtieth anniversary of his class. He found himself walking in the commencement procession next to Governor Charles Evans Hughes of New York. For once, the bearded inellectual, whom he privately mocked as “Charles the Baptist,” did not irritate him. They became so absorbed in conversation that they delayed general entry into Sanders Theatre.

Hughes wanted help. A mildly progressive Republican, he had served three and a half years in Albany at great personal cost, frustrated at every political turn by the state party machine. He was about to be relieved with a seat on the Supreme Court, courtesy of an admiring President Taft. Before resigning, he was determined to take the power of nomination to state offices away from party officials, and transfer it to the rank and file, voting in direct primaries. A bill to this effect had been blocked by standpatters throughout the regular session of the legislature. So he had convened a special session to pass it, in defiance of William Barnes, Jr., boss of the state GOP.

Hughes saw Roosevelt as the only New Yorker powerful enough to exert more influence than Barnes, and asked him if he would get behind the bill. Cannily, he emphasized58 that the lawmakers supporting it were all Roosevelt Republicans.

Many times59, over the years, Roosevelt had compared the workings of politics to those of a kaleidoscope. Brilliant, harmonious patterns, sometimes carefully shaken into shape, sometimes forming of their own accord, could at the slightest touch fall into jagged disarray, with clashing colors and shafts of impenetrable black. Hughes’s appeal had just such an effect on his current outlook. On this pleasant June day, under the elms of Harvard Yard, he was confronted with a situation of bewildering intricacy, sharp with factional danger.

He did not like60 Hughes, but then, neither did anybody at close range. It was impossible to warm to a man who exuded such cold correctness, and grinned with horse-toothed insincerity. However, there was no denying the governor’s intellectual brilliance (he was at home in Japanese, and in infinitesimal calculus), nor the acclaim he had won as an incorruptible advocate of the common good. Not to help him would be to signal approval of Barnes’s bossism. Even Taft supported61 the New York primary bill.

“HE WAS ABOUT TO BE RELIEVED WITH A SEAT ON THE SUPREME COURT.”

Charles Evans Hughes as governor of New York State. (photo credit i4.3)

By supporting it too, Roosevelt saw an opportunity to show that he was as willing to work with the President, as a Party regular, as with Hughes or any other moderate progressive. Surely the three of them, with their combined prestige, could swing the bill’s passage. Hughes would go out of office in glory, and establish himself on the Supreme Court, no doubt, as a progressive interpreter of the Constitution. Taft would be seen as hospitable to reasonable reform, and the Old Guard would have to accept that progressivism was now a permanent part of the Republican agenda. Best of all, Theodore Roosevelt would go down in history as a statesman who had made one final, selfless gesture of conciliation before retiring from Party politics.

“Our governor,”62 he announced at a luncheon for Hughes following the commencement ceremony in Sanders, “has a very persuasive way with him. I had intended to keep absolutely clear from any kind of public or political question after coming home, and I could carry my resolution out all right until I met the governor this morning, and he then explained to me that I had come back to live in New York now; that I had to help him out, and after a very brief conversation I put up my hands and agreed to help him.”

![]()

AFTER COFFEE63, ROOSEVELT seemed to want to retract his pledge. William N. Chadbourne, a Hughes lieutenant from New York County, said that party members who had gotten into politics because of him would be deeply disillusioned if “the old group” reasserted machine control in Albany.

The Colonel hesitated. “What shall I do?”64

“You’d better send a telegram to Lloyd Griscom.”

Griscom was chairman of the New York County Committee. Roosevelt sat down and scribbled the brief message that was to reinvolve him in politics. “I believe65 the people demand it,” he wrote of the direct primary bill. “I most earnestly hope that it will be enacted into law.”

![]()

EXHILARATED AS ALWAYS by the prospect of a fight, he went on to stay with Henry Cabot and Nanny Cabot Lodge at their summer home in Nahant, Massachusetts. Old mutual friends, the Winthrop Chanlers, were there too. Margaret Chanler wrote:

He was bursting66 with the things he wanted to tell us. He always liked to talk from a rocking chair; so one was brought out on the piazza, and the Lodge family, including the three children … and Winnie and I sat around him while he rocked vigorously and told one story after another, holding us enchanted, making us laugh until we cried and ached.… Some of his best stories were about King Edward’s funeral, or “wake” as he irreverently called it.…

I do not think the rest of us spoke a hundred words.… It was a manifestation of that mysterious thing, nth-powered vitality, communicating itself to the listeners.

Lodge was doubtful about Roosevelt’s New York venture, but pleased to hear that he was cooperating with the President on something.

Taft happened to be vacationing nearby on the North Shore. That made it impossible to put off their reunion any longer. So the following afternoon, with Lodge for company, Roosevelt donned a panama hat and motored up the coast to the “summer White House” in Beverly. It was a large rented cottage overlooking the surf at Burgess Point. Taft liked it more for the proximity of the Myopia golf links than for its ozone.

“I know this man67 better than you do,” a secret service agent, James Sloan, said to Archie Butt as they stood looking out for the Colonel’s automobile. “He will come to see the President today and bite his leg off tomorrow.”

Sloan despised Taft. He claimed he had once heard Roosevelt say, “Jimmy, I may68 have to come back in four years to carry out my policies.” Butt was ambivalent. He had become fond of his boss, finding him to be essentially good-natured and high-minded. When convinced of the rightness of a course of action, Taft pushed all obstacles out of his way, like an elephant rolling logs. However, again like an elephant, he had a tendency to listen to whichever trainer whispered in his ear.

He came out of the house69 now, as Roosevelt arrived. “Ah, Theodore, it is good to see you.”

“How are you, Mr. President? This is simply bully.”

“See here now, drop the ‘Mr. President.’ ”

“Not at all. You must be Mr. President and I am Theodore. It must be that way.”

They affected male exuberance, with shoulder punches reminiscent of their old friendship. But the strain between them was palpable. Taft led the way to a group of wicker chairs on the breezy side of the porch. Roosevelt said that he “needed rather than wanted” a Scotch and soda. Nobody else drank. Lodge and Butt puffed cigars.

To get a dialogue going, Taft raised the subject of Hughes’s primary bill. He confirmed that he would do all he could to help its passage. Roosevelt said that as a citizen of New York, he supported it too. This lame exchange went nowhere, and a telephone message from Lloyd Griscom gave them no encouragement. The chairman advised that every member of his committee looked on the fight as “hopeless.”

Taft and Roosevelt were clearly cast down. The President blustered that he would continue to issue appeals for votes.

“I wish they had both remained out of it,” Lodge muttered to Butt.

The arrival on the porch of Mrs. Taft, still half mute from her stroke, put a further damp on the proceedings. Roosevelt was sensitive enough not to force her into conversation. He rambled politely until she relaxed.

“Now, Mr. President,” Taft said, “tell me about cabbages and kings.”

Roosevelt was willing to oblige, but protested being called by his old title.

“The force of habit is very strong in me,” Taft said, with the simplicity that was a large part of his charm. “I can never think of you save as ‘Mr. President.’ ”

“TAFT LED THE WAY TO A GROUP OF WICKER CHAIRS ON THE BREEZY SIDE OF THE PORCH.”

The summer White House in Beverly, Massachusetts. (photo credit i4.4)

For an hour, Roosevelt told royal stories, and was funny enough about M. Pichon and “the poor little Persian” to get everyone laughing.

When he got up to go, Lodge informed him that there were about two hundred newsmen and photographers waiting outside the gates. Roosevelt asked Taft for permission to say that their visit had been personal, and delightful. “Which is true as far as I am concerned.”

“And more than true as far as I am concerned,” Taft answered. “This has taken me back to some of those dear old afternoons when I was Will and you were Mr. President.”

They parted with tacit acknowledgment that whatever remained of their friendship, “dearness” was no longer an option.

![]()

BEFORE LEAVING70 BOSTON for New York, Roosevelt paid a visit to Corey Hospital in Brookline, where Justice William Henry Moody lay bent and emaciated with rheumatoid arthritis. Only fifty-six, Moody was the last, and to some minds the most distinguished of his three appointments to the Supreme Court. Yet after four short terms, the justice had been felled by a streptococcal storm that left him unable to walk and deeply depressed.

It was a poignant reunion for both, and Roosevelt was mute about it afterward. He had looked to Moody71 to serve for many years as his representative on the bench, whenever cases arose that tested the constitutionality of his presidential policies. Back when nobody quite knew what progressive meant, Moody had been his most forward-looking cabinet officer, first as secretary of the navy, then as a resolutely antitrust attorney general—along with Root and Taft, one of the administration’s famous “Three Musketeers.”

Now that happy trio was disbanded. Aramis was bedridden for life, Athos intellectually stifled in the Senate, and Porthos no longer the jovial giant. Bereft of their company, whither D’Artagnan?

* Niece of Theodore Roosevelt.

* From now on, unqualified references to “Eleanor” should be understood to refer to Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., not her later more famous namesake.