28

‘When an army is inferior in number, inferior in cavalry and in artillery, it is essential to avoid a general action.’

Napoleon’s Military Maxim No. 10

‘It was Rome that Pompey needed to keep; there that he should have concentrated all his forces.’

Napoleon, Caesar’s Wars

On earlier occasions when France was in danger of invasion – in 1709, 1712, 1792–3 and 1799 – her large army and great border fortresses built in the seventeenth century by the military engineer Sébastien de Vauban had protected her.1 This time it was different. The sheer size of the Allied forces enabled them to outflank her formidable line of north-eastern forts – such as Verdun, Metz, Thionville and Mézières – and besiege them. Moreover, for this they could rely on their second-line troops, such as Landwehr, militias and the soldiers of minor German states. In 1792–3, the Austrian and Prussian armies invading France had numbered only 80,000 men, but were confronted by 220,000 Frenchmen under arms. In January 1814 Napoleon faced a total of 957,000 Allied troops with fewer than 220,000 men in the field – 60,000 of whom under Soult and 37,000 under Suchet were fighting Wellington’s Anglo-Spanish-Portuguese army in the south-west of France and 50,000 under Eugène were defending Italy. Napoleon’s army rarely numbered 70,000 in the coming campaign and was always dangerously weak in artillery and cavalry.2

Many were new conscripts, with little more than a coat and forage cap to distinguish them as soldiers. Yet they stayed with the colours; only 1 per cent of the 50,000 young conscripts who passed through the main depot at Courbevoie deserted during the 1814 campaign.3 Often depicted as an ogre keen to shore up his rule by throwing children into the charnel-house of war, Napoleon in fact wanted no such thing. ‘It is necessary that I get men, not children,’ he wrote to Clarke on October 25, 1813. ‘No one is braver than our youth, but . . . it is necessary to have men to defend France.’ In June 1807 he had told Marshal Kellermann that ‘Eighteen-year-old children are too young to be going to war far away.’4

• • •

Although Napoleon attempted to recreate the patriotism of 1793, even allowing street musicians to play the republican anthem the ‘Marseillaise’, which he had formerly banned, the old revolutionary cry of ‘La Patrie en danger!’ no longer had its electrifying effect.5 Still, he hoped the army and his own abilities might be enough to prevail. ‘Sixty thousand and me,’ he said, ‘together one hundred thousand.’6* However, if the French had been as motivated as Napoleon had hoped, a guerrilla movement would have broken out in France when the Allies invaded, yet none arose. ‘Public opinion is an invisible, mysterious, irresistible power,’ Napoleon mused later. ‘Nothing is more mobile, nothing more vague, nothing stronger. Capricious though it is, nevertheless it is truthful, reasonable, and right much more often than one might think.’7

Napoleon had entrenched the political and social advances of the Revolution largely by keeping the Bourbons out of power for fifteen years, after the ten between the Revolution and Brumaire, so a generation had passed since the fall of the Bastille and the French had grown accustomed to their newfound freedoms and institutions. But for many these benefits had been eclipsed by the price they had to pay in blood and treasure for the series of wars that six successive Legitimist coalitions had declared against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France. After twenty-two years of war the French people hankered for peace, and were willing to countenance the humiliation of Cossack campfires in the Bois de Boulogne to gain it. Napoleon soon discovered that he couldn’t even rely on his prefects, only two of whom – Adrien de Lezay-Marnésia at Strasbourg and De Bry at Besançon – obeyed his order to take refuge in the departmental capital and resist the invasion. The others either ‘retired’ – that is, fled to the interior at the first news of a skirmish – or, like Himbert de Flegny in the Vosges, simply surrendered. Some, such as Louis de Girardin of the Seine-Inférieure, hoisted the fleur-de-lys.8 Several prefects managed to rediscover their Bonapartism when Napoleon returned from Elba, only to re-rediscover their royalism after Waterloo.9 Claude de Jessaint, prefect of the Marne, managed to serve every regime without interruption or complaint from 1800 to 1838.

Napoleon was disappointed that so few Frenchmen answered the call to arms in 1814 – some 120,000 out of a nominal call-up several times that – but he hardly had the uniforms and muskets to furnish those who did arrive at the depots. The drafts of recent years had alienated the better-off peasants, his core constituency, and there had been violent anti-conscription riots. Under the Empire a total of 2,432,335 men were called up for conscription in the fifteen decrees, eighteen sénatus-consultes and one order of the Conseil that were issued between March 1804 and November 1813. Almost half of these came in 1813, when army recruiters ignored minimum age and height requirements.10 (Young Guard recruits could now be 5 foot 2 inches where previously they had been required to be 5 foot 4.) Between 1800 and 1813 draft evasion had dropped from 27 per cent to 10 per cent, but by the end of 1813 it was over 30 per cent and there were major anti-draft riots in the Vaucluse and northern departments.11 In Hazebrouck a mob of over 1,200 people nearly killed the local sous-préfet and four death sentences were imposed. In 1804 Napoleon had predicted that the unpopularity of conscription and the droits réunis would one day destroy him. As Pelet recorded, his ‘anticipation came literally to pass, for the words Plus de conscription – plus de droits réunis furnished the motto on the flags of the Restoration in 1814’.12 Taxes were extended from alcohol, tobacco and salt to include gold, silver, stamps and playing cards. The French paid, but resented it.13

After the Russian disaster Napoleon had had four months to rebuild and resupply his army before fighting resumed; now he had only six weeks. With the self-knowledge that was one of the more attractive aspects of his character, he said in early 1814: ‘I am not afraid to admit that I have waged war too much. I wanted to assure for France the mastery of the world.’14 That was not now going to happen, but he hoped that by striking hard blows using interior lines against whichever enemy force seemed to pose the greater threat to Paris, he might force acceptance of the Frankfurt bases for peace and so save his throne. At the same time he was philosophical about failure. ‘What would people say if I were to die?’ he asked his courtiers, and continued with a shrug before they were able to frame anything suitably oleaginous: ‘They would say, “Ouf!”’15

• • •

A spectator at Napoleon’s New Year’s Day levée in the Tuileries throne room in 1814 recalled: ‘His manner was calm and grave, but on his brow there was a cloud which denoted an approaching storm.’16 He considered the peace terms Britain had demanded at the end of 1813, but rejected the idea. ‘France without Ostend and Antwerp,’ he told Caulaincourt on January 4,

would not be on an equal footing with the other states of Europe. England and all the other powers recognised these limits at Frankfurt. The conquests of France within the Rhine and the Alps cannot be considered as compensation for what Austria, Russia and Prussia have acquired in Poland and Finland, and England in Asia . . . I have accepted the Frankfurt proposals, but it is probable that the Allies have other ideas.17

He might also have added Russian gains in the Balkans and British acquisitions in the West Indies to the list. The arguments he put for continued resistance were that ‘Italy is intact’, that ‘The depredations of the Cossacks will arm the inhabitants and double our forces’ and that he had enough men under arms to fight several battles. ‘Should Fortune betray me, my mind is made up,’ he said with defiant resolution. ‘I do not care for the throne. I shall not disgrace the nation or myself by accepting shameful conditions.’ He could take the betrayals of Bavaria, Baden, Saxony and Württemberg, and those of ministers such as Fouché and Talleyrand – even of Murat and his own sister Caroline – but not that of his greatest supporter up to that point: Fortune herself. Napoleon of course knew perfectly well intellectually that Destiny and Fortune did not control his fate, but the concepts nonetheless exercised a hold on him throughout his life.

‘Writing to a minister so enlightened as you are, Prince,’ Napoleon began a flattering letter to Metternich on January 16 in which he asked for an armistice with Austria.18 ‘You have shown me so much personal confidence, and I myself have such great confidence in the straightforwardness of your views, and in the noble sentiments which you have always expressed.’ He asked for the letter to remain secret. Of course it didn’t; Metternich shared it with the other Allies, but throughout the spring of 1814 Napoleon’s plenipotentiaries – principally Caulaincourt – kept up discussions with the Allies over the possibility of a peace treaty, whose terms fluctuated day by day with the fortunes of the armies. On January 21, in an attempt to win over popular opinion, the Pope was released from Fontainebleau and allowed to set off for the Vatican.

Murat’s treachery was sealed on January 11 when he signed an agreement with Austria to lead 30,000 men against Eugène in Italy in return for Ancona, Romagna and the security of his throne for himself and his heirs. ‘He isn’t very intelligent,’ Napoleon told Savary when Murat captured Rome just over a week later, ‘but he’d have to be blind to imagine that he can stay there once I’ve gone, or when . . . I’ve triumphed over all this.’19 He was right; within two years Murat would be shot by a Neapolitan firing squad. ‘The conduct of the King of Naples is infamous and there is no name for that of the queen’, was Napoleon’s response to his sister’s and brother-in-law’s behaviour. ‘I hope to live long enough to be able to revenge myself and France for such an insult and such fearful ingratitude.’20 By contrast, Pauline sent her brother some of her jewellery to help pay his troops. Joseph, who continued to call himself king of Spain even after Napoleon had allowed Ferdinand VII back to his country on March 24, stayed in Paris to guide the Regency Council.

‘To the courage of the National Guard I entrust the Empress and the King of Rome,’ Napoleon told its officers at an emotional ceremony in the Hall of the Marshals at the Tuileries on January 23. ‘I depart with confidence, am going to meet the enemy, and I leave with you all that I hold most dear; the Empress and my son.’21 The officers present cried ‘Vive l’Impératrice!’ and ‘Vive le Roi de Rome!’, and Pasquier ‘saw tears running down many faces’.22 Napoleon understood the propaganda value of his infant son, and ordered an engraving to be made of him praying, with the inscription: ‘I pray to God to save my father and France.’ He adored the boy, who could induce strange reflections in him; once when the infant fell and slightly hurt himself, causing a great commotion, ‘the Emperor became very pensive and then said: “I’ve seen one cannonball take out a single line of twenty men.”’23 For all his proclaimed ‘confidence’ in victory, Napoleon burned his private papers on the night of the 24th, before leaving Paris for the front at six o’clock the next morning. He was never to see his wife or son again.

• • •

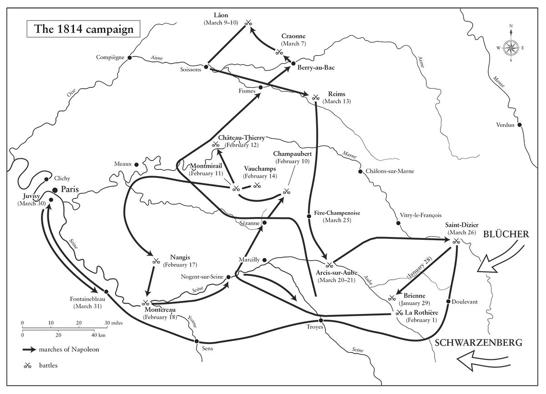

The Champagne region lies to the east of Paris and is crossed by the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne, river valleys that were the natural corridors for the Allied advance on the capital. The fighting there was to take place during the harshest winter in western Europe in 160 years; even the Russians were astonished at how cold it was. Hypothermia, frostbite, pneumonia, exhaustion and hunger were ever present. Typhus was again a particular concern, especially after a major outbreak at the Mainz camp. ‘My troops! My troops! Do they really imagine I still have an army?’ Napoleon told his prefect of police, Pasquier, at this time. ‘Don’t they realise that practically all the men I brought back from Germany have perished of that terrible disease which, on top of all my other disasters, proved to be the last straw? An army indeed! I shall be lucky if, three weeks from now, I manage to get together 30,000 to 40,000 men.’24 Nine of the campaign’s twelve battles were fought in an area of just 120 miles by 40 – half the size of Wales – on land that was flat and covered in snow, which was ideal country for cavalry, had he had any. Facing him were the two main Allied armies, Blücher’s Army of Silesia and Schwarzenberg’s Army of Bohemia, about 350,000 men. In all, the Allies fielded nearly a million troops.*

Whereas in 1812 Napoleon’s army had grown so large that he had been forced to rely on his marshals taking largely independent commands, once it had contracted to 70,000 he was able to control it in the direct and personal way he had in Italy. Berthier and seven other marshals were with him – Ney, Lefebvre, Victor, Marmont, Macdonald, Oudinot and Mortier – and he was able to use them much as he had when some of them had been mere generals or divisional commanders over a decade before; each of them had only 3,000 to 5,000 troops under his command. (Of the others, Bernadotte and Murat were now fighting against him, Saint-Cyr had been captured, Jourdan, Augereau and Masséna were governing military districts, Soult and Suchet were in the south, and Davout was still holding out in Hamburg.)

Taking command of only 36,000 men and 136 guns at Vitry-le-François on January 26, Napoleon ordered Berthier to distribute 300,000 bottles of champagne and brandy to the troops there, saying, ‘It’s better that we should have it than the enemy.’ Seeing that while Blücher had pushed well forward, Schwarzenberg had veered slightly away from him, he attacked the Army of Silesia at Brienne in the afternoon of the 29th.25 ‘I could not recognize Brienne,’ Napoleon said later. ‘Everything seemed changed; even distances seemed shorter.’26 The only place he recognized was a tree under which he had read Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered. Napoleon’s guide during the battle was the local curate, one of his old schoolmasters, who rode Roustam’s horse, which was later killed by a cannonball immediately behind Napoleon.27 It was the surprise storming of the chateau at Brienne, during which Blücher and his staff were nearly captured, and its retention despite vigorous Russian counter-attacks, that helped give Napoleon his victory. ‘As the battle did not begin until an hour before nightfall, we fought all night,’ Napoleon reported to his war minister, Clarke. ‘If I had had older troops I should have done better . . . but with the troops I have we must consider ourselves lucky with what happened.’28 He had come to respect his opponent and said of Blücher, ‘If he was beaten, the moment afterwards he showed himself ready as ever for the fight.’29 On Napoleon’s return to his headquarters at Mézières, a Cossack band came close enough for one of them to thrust a lance at him, only to be shot dead by Gourgaud. ‘It was very dark,’ recalled Fain, ‘and amidst the confusion of the night encampment, the parties could only recognize each other by the light of the bivouac fires.’30 Napoleon rewarded Gourgaud with the sword he had worn at Montenotte, Lodi and Rivoli.

When he took stock of the situation after the battle he found he had lost 3,000 casualties, and Oudinot was wounded yet again. Retreating from Brienne to Bar-sur-Aube, the Prussians were joined by some of Schwarzenberg’s Austrian contingents in the plain between the two towns. Napoleon couldn’t refuse battle as the bridge over the Aube at Lesmont, the principal line of retreat, had been destroyed earlier in the campaign in order to stop Blücher’s advance on Troyes. He had stayed a day too long, and although his force had been reinforced by Marmont’s corps to number 45,000 men it was attacked across open ground by 80,000 Allies at La Rothière, 3 miles from Brienne, on February 1. The French defended the village until dark but Napoleon lost nearly 5,000 men which he could ill afford, although the Allies lost more. He also lost seventy-three guns, and was forced to retreat, sleeping in Brienne Château and ordering a retreat to Troyes over the barely rebuilt Lesmont bridge. The next day Napoleon wrote to Marie Louise telling her not to watch L’Oriflamme at the Opéra: ‘So long as the territory of the Empire is overrun by enemies, you should go to no performances.’31

After La Rothière, believing Napoleon to be retreating to Paris, the Allies separated again, Schwarzenberg heading due west to the valleys of the Aube and Seine while Blücher marched to the Marne and Petit-Morin valleys on a parallel line, 30 miles to the north. Their armies were really too large to march together logistically, and the gap between them allowed Napoleon to operate deftly between the two forces. It was to these next four battles that Wellington was referring when he said of Napoleon’s 1814 campaign, it ‘has given me a greater idea of his genius than any other. Had he continued that system a little longer, it is my opinion that he would have saved Paris.’32

‘The enemy troops behave horribly everywhere,’ Napoleon wrote to Caulaincourt from a deserted Brienne. ‘All the inhabitants seek refuge in the woods; no more peasants are found in the villages. The enemy eat up everything, take all the horses, cattle, clothes and all the rags of the peasants; they beat everyone, men and women, and commit rape.’33 Of course Caulaincourt, who had been on the Russian campaign, knew perfectly well how invading armies, including the French, behaved. Was this letter written for the record? The next sentence gives a clue to its intent: ‘The picture which I have just seen with my own eyes should make you understand easily how much I desire to extricate my people as soon as possible from this state of misery and suffering, which is truly terrible.’34 Napoleon was presenting a humanitarian rationale to Caulaincourt for accepting decent terms if they were offered at the peace negotiations that had begun on February 5 at Châtillon-sur-Seine.*

The Congress of Châtillon sat until March 5. Knowing that they had the upper hand through sheer weight of numbers, the Allies dropped the proposal for France to return to her ‘natural’ frontiers, as they had suggested at Frankfurt, and, led by the British plenipotentiary Lord Aberdeen, demanded that France return to her 1791 frontiers instead, which didn’t include any part of Belgium. At his coronation Napoleon had sworn ‘to maintain the integrity of the territory of the Republic’ and he meant to keep to it. ‘How can you expect me to sign this treaty, and thereby violate my solemn oath!’ he asked Berthier and Maret, who were urging him to end the war even on these punishing terms.

Unexampled misfortunes have torn from me the promise of renouncing the conquests that I have myself made, but shall I renounce those that were made before me! Shall I violate the trust that was so confidently reposed in me? After the blood that has been shed, and the victories that have been gained, shall I leave France smaller than I found her? Never! Can I do so without deserving to be branded a traitor and a coward?35

He later admitted that he felt he couldn’t give up Belgium because ‘the French people would not allow [me] to remain on the throne except as a conqueror’. France, he said, was like ‘air compressed within too small a compass, the explosion of which was like thunder’.36 Against the advice of Berthier, Maret and Caulaincourt, therefore, Napoleon counted on Allied disunity and French patriotism – despite little evidence of either – and fought on. As his soldiers were now living off the backs of their own countrymen, he bemoaned the fact that ‘The troops, instead of being their country’s defenders, are becoming its scourge.’37

The treasury’s bullion was loaded onto carts in the courtyard of the Tuileries on February 6 and secretly taken out of Paris. Denon requested permission for the Louvre’s pictures to be removed, which Napoleon did not grant on grounds of morale. Napoleon tried to keep Marie Louise’s spirits up, writing at 4 a.m. that day: ‘I’m sorry to hear you are worrying; cheer up and be gay. My health is perfect, my affairs, while none too easy, are not in bad shape; they have improved this last week, and I hope, with the help of God, to bring them to a successful issue.’38 The next day he wrote to Joseph, ‘I fervently hope that the departure of the Empress will not take place,’ otherwise ‘the consternation and despair of the populace might have disastrous and tragic results.’39 Later that same day he told him: ‘Paris is not in such straits as the alarmists believe. The evil genius of Talleyrand and those who sought to drug the nation into apathy have hindered me from summoning it to arms – and see to what pass they have brought us!’40 He had finally recognized the truth about Talleyrand – who with Fouché was planning a coup in Paris and openly discussing surrender terms with the Allies.* Napoleon could not bring himself to accept that the apathy of the nation in the face of invasion was a reflection of its loss of appetite for war. Writing to Cambacérès about the new mania for forty-hour ‘misery’ church services praying for salvation from the Allies, he asked, ‘Have the Parisians gone mad?’ To Joseph he commented, ‘If these monkey tricks are continued we’ll all be afraid of death. Long ago it was said that priests and doctors render death painful.’41

All the leaders who were planning to oust him – Talleyrand, Lainé, Lanjuinais, Fouché and others – had opposed or betrayed him in the past, yet he hadn’t imprisoned them, let alone executed them. In this, Napoleon resembled his hero Julius Caesar, who was assassinated by people to whom he had shown clemency and decided not to mark down for the judicial murders that Sulla had employed before him, and Octavian would afterwards.

• • •

As the political situation darkened at Châtillon, Napoleon began to think about his own death, writing to Joseph about the prospect of Paris falling. ‘When it comes I will no longer exist, consequently it is not for myself that I speak,’ he said on February 8. ‘I repeat to you that Paris shall never be occupied during my life.’42 Joseph replied, not very helpfully, ‘If you desire peace, make it at any price. If you cannot do so, it is left to you to die with fortitude, like the last emperor of Constantinople.’43 (Constantine XI had died in battle there in 1453 when the city was overwhelmed by the Ottomans.) Napoleon more practically replied, ‘That is not the question. I am just working out a way of beating Blücher. He is advancing along the road from Montmirail. I shall beat him tomorrow.’44 He did indeed, and then again and again in a series of high-tempo victories that, despite being very close to each other geographically and chronologically, were quite separate battles.

Posting Victor at Nogent-sur-Seine and Oudinot at Bray, Napoleon marched north to Sézanne with Ney and Mortier, and was joined on the way by Marmont. The Army of Silesia was still moving parallel to the Army of Bohemia but at a much faster pace. As it pulled too far ahead it presented not just its flank but almost its rear to Napoleon, who was poised between the two Allied armies. Spotting that the Russians had no cavalry with them and were isolated, Napoleon struck at their open flank and fell upon the centre of Blücher’s over-extended army at Champaubert on February 10, destroying the best part of General Zakhar Dmitrievich Olsufiev’s corps and capturing an entire brigade, for the loss of only six hundred killed, wounded and missing. He dined with Olsufiev at Champaubert’s inn that evening, writing to Marie Louise, to whom he sent Olsufiev’s sword, ‘Have a salute fired at Les Invalides and the news published at every place of entertainment . . . I expect to reach Montmirail at midnight.’45 The chorus of the Opéra, where Jean-Baptiste Lully’s Armide was being performed, sang ‘La Victoire est à Nous’.

On the 11th General von Sacken broke from the Trachenberg strategy and attacked Napoleon directly at Marchais on the Brie plateau overlooking the Petit-Morin valley.* Ney defended Marchais while Mortier and Friant counter-attacked the Russians at L’Épine-aux-Bois and Guyot’s cavalry came around their rear, routing the Russians and Prussians. It was a classic example of Napoleon’s tactic of defeating the main enemy force (under Sacken) while successfully holding off the enemy’s secondary force (under the command of Yorck). Napoleon slept that night in a farmhouse at Grénaux, where, Fain recalled, ‘the dead bodies having been removed, the headquarters were established’.46 Writing to his wife at 8 p.m., Napoleon ordered a salute of sixty guns fired in Paris, claiming that he had taken ‘the whole of their artillery, captured 7,000 prisoners, more than 40 guns, not a man of this routed army escaped’.47 (He had actually captured 1,000 prisoners and 17 guns.)

The fact that many of Sacken’s and Yorck’s soldiers had escaped was evident the next day, when Napoleon attacked them at Château-Thierry, despite his being outnumbered two to three. Spotting that a Russian brigade was isolated on the extreme right of the Allied line, Napoleon ordered his few cavalry to ride them down, which they did, capturing a further fourteen guns.48 Macdonald’s failure to capture the bridge at Château-Thierry allowed the Allies to escape to the north side of the Marne, however. ‘I’ve been in the saddle all day, ma bonne Louise,’ Napoleon told the Empress from the chateau, along with another tissue of propaganda data, ending ‘My health is very good.’49 For all these victories over the Army of Silesia, nothing could make it possible for Oudinot’s corps of 25,000 men and Victor’s of 14,000 to hold the five bridges over the Seine and prevent Schwarzenberg’s 150,000-strong Army of Bohemia from crossing.50

On February 14 Napoleon scored yet another victory over Blücher, at Vauchamps. Leaving Mortier at Château-Thierry at 3 a.m., he doubled back to support Marmont, whom Blücher was forcing to retreat from Étoges to Montmirail. A sudden assault of 7,000 Guard cavalry forced Blücher and Kleist to retreat to Janvilliers, where Grouchy attacked their flank and Drouot’s fifty guns wrought further havoc. This secured the Marne from the Silesian army, which was beaten and dispersed, though not ‘annihilated’ as the official bulletin claimed. Napoleon could now hasten to confront the Army of Bohemia, which had forced Oudinot and Victor back from the bridges over the Seine and was driving deep into France, capturing Nemours, Fontainebleau, Moret and Nangis.*Further south, in a sure sign of national demoralization, French towns and cities were starting to surrender even to small Allied units. Langres and Dijon fell without a fight, Épinal surrendered to fifty Cossacks, Mâcon to fifty hussars, Reims to a half-company, Nancy to Blücher’s outriding scouts, and a single horseman took the surrender of Chaumont.51 Napoleon’s hopes for a national uprising against the invader, with guerrilla actions to rival those of Spain and Russia, were not going to be realized.

Pausing only to send 8,000 Prussian and Russian prisoners-of-war to be marched down the Parisian boulevards to substantiate his (accurate) claim of four victories in five days at Champaubert, Montmirail, Château-Thierry and Vauchamps, Napoleon left his headquarters at Montmirail at 10 a.m. on February 15 to join Victor’s and Oudinot’s corps at Guignes, 25 miles south-east of Paris. By the evening of the 16th he had placed his army across the main road to the capital. He found Schwarzenberg’s force strung out over 50 miles and hoped to defeat it piecemeal, writing to Caulaincourt: ‘I am ready to cease hostilities and to allow the enemy to return home tranquilly, if they will sign the preliminary bases of the propositions of Frankfurt.’52 As Lord Aberdeen was still refusing to allow Napoleon to retain control over Antwerp, however, the fighting had to continue.

On February 17 Napoleon marched on Nangis, where Wittgenstein had three Russian divisions. He attacked with Kellermann on the left and General Michaud on the right, broke the Russian squares and smashed them with Drouot’s guns. To secure the bridges over the Seine he then split his forces at the Nangis road junction. Victor headed for the bridge at Montereau 12 miles to the south and on the way attacked a Bavarian division at Villeneuve, but he failed to press home his advantage after a long march and many days of continual fighting. In one of his few unwarranted substitutions, Napoleon replaced him with General Étienne Gérard. He also humiliated General Guyot in front of his men, and ordered a court martial of General Alexandre Digeon when his battery ran out of ammunition. ‘Napoleon acted with a degree of severity in which he was himself astonished,’ wrote his apologist Baron Fain, ‘but which he conceived to be necessary in the imperious circumstances of the moment.’53 Military orders are naturally terse; Napoleon was often rude to his senior commanders, who were brave and conscientious soldiers, albeit of varying degrees of competence. Yet even now he could contemplate the situation with a degree of humour. ‘Should fortune continue to favour us’, he wrote to Eugène, ‘we shall be able to preserve Italy. Perhaps the King of Naples will then change sides again.’54

Arriving at Montereau at the confluence of the Seine and the Yonne with the Imperial Guard at 3 p.m. on the sunny and cloudless day of February 18, Napoleon set up batteries on the Surville heights above the town, firing canister shot at full range at the Allied infantry crossing the two bridges and preventing the Württemberger engineers from demolishing them. (Looking up from the bridges the heights look like a hillock, but from the place he chose to site his guns on top of them it immediately becomes clear that they dominate the town.) The Austrians were attacked by General Louis Huguet-Chateau, whose force was beaten off, though Chateau himself was killed. Napoleon then sent in a cavalry charge led by General Pajol that crashed down the steep cobbled road, across both bridges and into the town itself.* ‘I am happy with you,’ he said to Pajol afterwards, as heard by Pajol’s aide-de-camp, Colonel Hubert Biot. ‘If all my generals had served me as you did, the enemy wouldn’t be in France. Go take care of your wounds, and when you’ve recovered I will give you ten thousand horses to say hello to the King of Bavaria from me! . . . If the day before yesterday in the morning I had been asked for four million francs to have the Montereau bridges at my disposal, I would have unhesitatingly given them.’55 Biot afterwards joked to Pajol that in that case the Emperor might have parted with 1 million to reward him without too much difficulty.

The next day Napoleon denied to Caulaincourt that the Austrians had reached Meaux, but they had. Sacken’s cannon were now distinctly audible in Paris itself, although the Russian commander pulled back on the news that Napoleon was intending to attack Blücher again.56 That day Napoleon wrote angrily to his police minister, the usually reliable Savary, for permitting poems to be published in the Paris papers saying how great a soldier he was because he was constantly defeating forces thrice his number. ‘You must have lost your heads in Paris to say such things when I am constantly giving out that I have 300,000 men,’ wrote Napoleon, who had in fact commanded only 30,000 at Montereau; ‘it is one of the first principles of war to exaggerate your forces. But how can poets, who endeavour to flatter me, and to flatter the national self-love, be made to understand this?’57 To Montalivet, who had written of France’s desire for peace, Napoleon retorted, ‘You and [Savary] know no more of France than I know of China.’58

In a desperate attempt to split the Allies, Napoleon wrote to Emperor Francis on February 21 asking for the Frankfurt bases of peace to be re-offered ‘without delay’, saying that the Châtillon terms were ‘the realisation of the dream of Burke, who wished France to disappear from the map of Europe. There are no Frenchmen who would not prefer death to conditions which would render them the slaves of England.’ He then raised the spectre of a Protestant son of George III on the throne of Belgium.59 As with all his earlier attempts, this had no effect.

Concerned that Augereau, whom he had made commander of the Army of the Rhône but whose heart was no longer in the fight, had still not made a significant contribution to the campaign despite having been reinforced with troops from Spain, Napoleon wrote to him in Lyons: ‘If you are still the Augereau of Castiglione, keep the command; but if your sixty years weigh upon you, hand over the command to your senior general.’60 This only had the effect of further alienating the disillusioned old warrior, who failed to march north but instead evacuated Lyons and fell back to Valence. Ney and Oudinot broached the subject of peace in a conversation with Napoleon at Nogent on the 21st, which ended in a severe reprimand and an invitation to lunch. When Wellington crossed the Adour and defeated Soult soundly at Orthez on February 27, however, the strategic situation became even more desperate.61

Although armistice discussions were carried on by the Comte de Flahaut at Lusigny between February 24 and 28, which Napoleon hoped might end with a return to the Frankfurt bases, he insisted that the fighting must carry on. ‘I do not intend to be fettered by these negotiations,’ he told Fain, as he had been during the Armistice of Pleischwitz the previous year. On March 1, 1814 the Allies signed the Treaty of Chaumont with each other, agreeing to make no separate peace with Napoleon, declaring their aim of each contributing an army of 150,000 men to oust him and end French influence over Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, Spain and the Netherlands.

As her husband’s Empire was on the brink of catastrophe, Marie Louise revealed herself to be a lightweight young woman quite unsuited to the rigours of a crisis. ‘I have had no news from the Emperor,’ she wrote in her diary. ‘He is so casual in his ways. I can see he is forgetting me.’ From his replies to the trivialities in her letters about court tittle-tattle, scenes with the King of Rome’s governess, matters of etiquette and so on, it seems she was either unaware of or uninterested in the earthquake taking place around her. Perhaps she was simply concentrating on the prattle of the pet parrot given her by her lady-in-waiting the Duchesse de Montebello (Lannes’ widow) in order to drown out the noise of a collapsing empire and the war between her husband and her father. She and her ladies-in-waiting shredded linen to make dressings for the wounded, but what really interested her were sketching, handkerchief-embroidery, music, cards and flowers. She even asked whether she could write to Caroline Murat, to which Napoleon replied: ‘My answer is No: she behaved improperly towards me, who of a mere nobody made a queen.’62 On March 2 Napoleon tried to put her to some useful work organizing the donation to the military hospitals of 1,000 stretchers, straw mattresses, sheets and blankets from Fontainebleau, Compiègne, Rambouillet and other palaces. He added that he was chasing the Prussians, ‘who are much exposed’, and the next day he erroneously reported the wounding of ‘Bulcher’ (sic).63

On March 6 Victor – to whom Napoleon had given a division of the Young Guard after his unfair demotion – captured the heights above the town of Craonne, 55 miles north-east of Paris, even though the plateau was protected by three ravines and the Russians were covering the defile with sixty guns. At the battle there the next day Napoleon attempted unsuccessfully to turn both flanks but finally had to resort to a bloody frontal attack to defeat Blücher’s Russian advance guard. Drouot’s aggressive use of an eighty-eight-gun battery, and Ney’s debouching on to the right wing, finally won Napoleon the field of battle after one of the bloodiest clashes of the campaign. The fighting took place all along the 2-mile-long plateau of the Chemin des Dames, from the Hurtebise farmhouse to the village of Cerny, between 11 a.m., when the farm was cleared, and 2.30 p.m. The very narrow front, hardly more than the width of a single field, contributed significantly to the high losses on both sides. Today’s idyllic, poppy-filled meadow gives no indication of the bitterness of the resistance of the Russians, who were able to retreat unmolested so exhausted were the French. Craonne was a victory, but when news of it reached Paris the Bourse fell on the assumption that the war would now continue.64

The next day both sides rested and reorganized. On the 9th and 10th Napoleon attacked the main Prussian army at Lâon, the well-fortified capital of the Aisne department 85 miles north-east of Paris. (From the walls of Lâon one can see the entire battlefield laid out below, just as the Prussian and Russian officers did.) In an inversion of Austerlitz, the sun burned off the mist on the plain by 11 a.m., allowing Blücher’s staff to count Napoleon’s army of only 21,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry, against 75,000 Allied infantry and 25,000 cavalry, although Napoleon had more guns. So respectful were they of his skill as a tactician, however, that they assumed there must be a ruse, and didn’t counter-attack in full force, though they did engage with larger numbers.

Marmont was only 4 miles away with 9,500 men and 53 guns, but he might not have heard the battle being fought on the plain and so failed to support his Emperor. Because of his later conduct Marmont has been accused of treachery at Lâon, but a strong wind blowing from the west on that battlefield could have drowned out the noise. Yet nothing can excuse him and his staff for not posting sentries properly on the evening of the 9th, as a Prussian corps under Yorck and Kleist mounted a successful surprise night-raid on his camp which completely scattered his force. Napoleon disastrously chose to renew his attack the next day, not realizing until 3 p.m. that he was facing a vastly superior Allied force. He lost 4,000 killed and wounded, with 2,500 men and 45 guns captured.

Though his army had been reduced from 38,500 (including Marmont’s troops) to fewer than 24,000 by the end of March 10, Napoleon showed extraordinary resilience and moved off immediately to attack Reims, hoping to cut through the Allied lines of communication. Yet that same day, the whole concept of lines of communication started to become moot when a letter from Talleyrand arrived at Tsar Alexander’s headquarters, telling him that the siege preparations in Paris had been badly neglected by Joseph, and encouraging the Allies to march straight on to the capital.

• • •

Talleyrand’s final defection was only to be expected – he had been planning for it on and off for the five years since Napoleon had called him a shit in silk stockings – but on March 11 Napoleon was given to understand that own his brother Joseph was making a more intimate betrayal by apparently attempting to seduce his wife. ‘King Joseph says very tiresome things to me,’ Marie Louise told the Duchesse de Montebello.65 Writing from Soissons, Napoleon was clearly concerned. ‘I have received your letter,’ he told the Empress.

Do not be too familiar with the King; keep him at a distance, never allow him to enter your private apartments, receive him ceremoniously as Cambacérès does, and when in the drawing room do not let him play the part of adviser to your behaviour and mode of life . . . When the King attempts to give you advice, which it is not his business to do, as I am not far away from you . . . be cold to him. Be very reserved in your manner to the King; no intimacy and whenever you can do so, talk to him in the presence of the Duchess and by a window.66

Was Joseph trying to play the role of Berville in Clisson et Eugénie? Napoleon suspected so, writing to the Empress the next day:

Will it be my fate to be betrayed by the King? I would not be surprised if such were to be the case, nor would it break down my fortitude; the only thing that could shake it would be if you had any intercourse with him behind my back and if you were no longer to me what you have been. Mistrust the King; he has an evil reputation with women and an ambition which has been habitual with him in Spain . . . I say it again, keep the King away from your trust and yourself . . . All this depresses me rather; I need to be comforted by the members of my family, but as a rule I get nothing but vexation from that quarter. On your part, however, it would be both unexpected and unbearable.67

To Joseph himself Napoleon wrote: ‘If you want to have my throne, you can have it, but I ask of you only one favour, to leave me the heart and the love of the Empress . . . If you want to perturb the Empress- Regent, wait for my death.’68* Was Napoleon becoming paranoid in these letters? Joseph had stopped visiting his mistresses, the Marquesa de Montehermoso and the Comtesse Saint-Jean d’Angély, and within a year Marie Louise would indeed betray Napoleon sexually, with an enemy general.69 Marmont recorded how hubristic and divorced from reality Joseph had by now become, believing that Napoleon had removed him from his command in Spain in 1813 ‘because he was jealous of him’, and insisting that he could have ruled Spain successfully, recognized by the rest of Europe, ‘without the army, without my brother’.70 Such views, if Marmont wasn’t inventing them, were of course totally delusory.

On March 16 Napoleon gave Joseph specific orders: ‘Whatever happens, you must not allow the Empress and the King of Rome to fall into the enemy’s hands . . . Stay with my son and do not forget that I would sooner see him drowned in the Seine than captured by the enemies of France. The tale of Astyanax, captive of the Greeks, has always struck me as the saddest page of history.’71 The infant Astyanax, son of Prince Hector of Troy, according to Euripides and Ovid, was flung off the city walls – although according to Seneca he jumped. ‘Give a little kiss to my son,’ Napoleon wrote less melodramatically the same day to Marie Louise. ‘All you tell me about him leads me to hope that I shall find him much grown; he will soon turn three.’72

• • •

After taking Reims by storm on March 13, Napoleon fought at Arcis-sur-Aube on the 20th and 21st against the Austrians and Russians under Schwarzenberg, the fourth and last defensive battle of his career. He had with him only 23,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry and he thought he was confronting the Allied rearguard, whereas in fact there were over 75,000 soldiers of the Army of Bohemia in the fields beyond the bridge over the fast-flowing, caramel-coloured river. During the 1814 campaign, Napoleon covered over 1,000 miles and slept in forty-eight different places in sixty-five days. Yet for all this movement, his three defeats – La Rothière, Lâon and Arcis – all came from staying too long in the same place, as he did at Arcis on the 21st. ‘I sought a glorious death disputing foot by foot the soil of the country,’ Napoleon later reminisced of the battle, where a howitzer shell disembowelled a horse he was riding but left him unscathed. ‘I purposely exposed myself; the balls flew around me, my clothes were pierced, but none reached me.’73 He later regularly mentioned Arcis as the place – along with Borodino and Waterloo – where he would have most liked to have died.

On March 21 Napoleon moved on Saint-Dizier, where he again hoped to cut the Allies’ lines of communications. If Paris could only hold out for long enough he could then attack them in the rear. Yet did the Parisians have the stomach for a siege, or would they collapse as the rest of France was doing? That same day Augereau had allowed the Austrians to take Lyons without bloodshed. Napoleon nonetheless hoped that the workers of Paris and the National Guard might barricade the streets and keep the Allies out, telling Caulaincourt on the 24th, ‘Only the sword can decide the present conflict. One way or the other.’74

On the 23rd the Allies captured a courier with a letter from Napoleon which told Marie Louise that he was heading for the Marne ‘in order to push the enemy as far as possible from Paris and to draw closer to my positions’. Also seized was a letter from Savary imploring Napoleon to return to Paris as the regime was crumbling and being openly conspired against.75 Both confirmed the Allied high command in their plan to move on Paris. Sending his light cavalry to Bar-sur-Aube and the Guard towards Brienne, Napoleon harried them as best he could, but although he beat back clouds of Russian cavalry in a series of skirmishes around Saint-Dizier the next day, the main bodies of the Allied armies were now all converging on the badly neglected defences of Paris.76 The capital’s lack of strong fortifications was a fault Napoleon later acknowledged fully; he had planned to put a battery of long-range cannon on top of both the Arc de Triomphe and the Temple of Victory at Montmartre, but neither was ready.77

On March 27 Macdonald brought Napoleon a copy of an enemy Order of the Day, announcing that Marmont and Mortier had been defeated at the battle of Fère-Champenoise on the 25th. He couldn’t believe it was true and argued that since the order was dated March 29 it must be Allied propaganda. Drouot, whom Napoleon nicknamed ‘the sage of the Grande Armée’ for his wise counsel, pointed out that the printer had inserted a ‘6’ upside-down in error. ‘Quite right,’ Napoleon exclaimed on checking, ‘that changes everything.’78 He now needed to get to Paris at all costs. That evening he gave the order to march away from Saint-Dizier via the road to Troyes, his left flank covered by the Seine, ready to strike towards Blücher on his right.

At a long meeting in Paris on the night of the 28th Joseph, who had completely lost his nerve, had persuaded the Regency Council that it was Napoleon’s wish for the Empress and government to escape from the capital and move to Blois on the Loire, using as evidence a letter that was a month old and had since been twice superseded by different orders. He was supported by Talleyrand (who was already drawing up lists of ministers to serve in his post-Napoleonic provisional government), the regicide Cambacérès (who didn’t want to fall into Bourbon hands), Clarke (whom Louis XVIII soon afterwards made a peer of France) and the Empress herself, who ‘was impatient to get away’.79 Savary, Pasquier and the president of the Legislative Body, the Duc de Massa, thought that the Empress would get much better terms for herself and her son if she remained, and Hortense warned her that ‘In leaving Paris, you lose your crown’, but at 9 a.m. on March 29 the imperial convoy left the capital for Rambouillet with 1,200 men of the Old Guard, reaching Blois by April 2.80 Cambacérès, ‘accompanied by some faithful friends who would not leave him’, took the seals of state to Blois in a grand mahogany box.81

• • •

On Wednesday, March 30, 1814, as Napoleon moved from Troyes via Sens towards Paris as fast as his soldiers could march, 30,000 Prussians, 6,500 Württembergers, 5,000 Austrians and 16,000 Russians under Schwarzenberg engaged 41,000 men under Marmont and Mortier in Montmartre and other Parisian suburbs. Despite putting out a proclamation on March 29 saying ‘Let us arm to protect the city, its monuments, its wealth, our wives and children, all that is dear to us’, Joseph left the city once the fighting started the next day.82 Marmont and Mortier were hardly facing impossible odds, yet they considered the situation irretrievable and succumbed to Schwarzenberg’s threats to destroy Paris. At seven o’clock the next morning, they opened talks with a view to surrendering the city.83 Although Mortier marched his corps out of the city to the south-west, Marmont kept his corps of 11,000 men stationary over the coming days. As the enemy closed in, the elderly Marshal Sérurier, governor of Les Invalides, supervised the burning and hiding of trophies, including 1,417 captured standards and the sword and sash of Frederick the Great.

The Emperor reached Le Coeur de France, a staging post-house at Juvisy only 14 miles from Paris, sometime after 10 p.m. on March 30. General Belliard arrived there soon after to inform him of Paris’s capitulation after only one day’s indecisive fighting. Napoleon called Berthier over and plied Belliard with questions, saying ‘Had I arrived sooner, all would have been saved.’84 Exhausted, he sat for over a quarter of an hour with his head in his hands.85* He considered simply marching on to Paris regardless of the situation there, but was persuaded not to by his generals.86 Instead he became the first French monarch to lose the capital since the English occupation of 1420–36. He sent Caulaincourt to Paris to sue for peace and went to Fontainebleau, where he arrived at 6 a.m. on the 31st. An auto-da-fé of flags and eagles was conducted in the forest there (although some escaped the bonfire and can be seen in the Musée de l’Armée in Paris today).87

When the Allied armies entered Paris by the Saint-Denis gate on April 1, with white ribbons on their arms and green sprigs in their shakos, they were greeted by the populace with the exuberance that victorious armies always tend to receive. Lavalette was particularly disgusted by the sight of ‘Women dressed as for a fete, and almost frantic with joy, waving their handkerchiefs crying: “Vive l’Empereur Alexander!”’88 Alexander’s troops bivouacked on the Champs-Élysées and Champ de Mars. There was no evidence that Parisians were willing to burn down their city sooner than cede it to their enemies, as the Russians had burned Moscow only eighteen months previously. The fickleness of the rest of the Empire might be judged from a Milanese deputation then on a visit to Paris to congratulate the man they had intended to call ‘Napoleon the Great’ for triumphing over all his enemies. On approaching the capital and hearing that it was being besieged they nonetheless decided to press on, and when they arrived promptly offered their congratulations to the Allies ‘on the fall of the tyrant’.89

Fifteen years after supporting Napoleon’s coup d’état at Brumaire, Talleyrand launched his own coup on March 30, 1814 and set up a provisional government in Paris that immediately began peace negotiations with the Allies.90 Although Tsar Alexander had considered alternatives to restoring the Bourbons, including Bernadotte, the Orleanists or perhaps even a regency for the King of Rome, he and the other Allied leaders were persuaded by Talleyrand to accept Louis XVIII. Another regicide, Fouché, was brought into the provisional government, and on April 2 the Senate passed a sénatus-consulte deposing the Emperor and inviting ‘Louis Xavier de Bourbon’ to assume the throne. The provisional government also released all French soldiers from their oath of allegiance to Napoleon. When this was circulated among the troops it was noted that although the senior officers took it seriously, most of the other ranks treated it with contempt.91 (One can be too pious about the solemnity of these oaths of loyalty, of course; Napoleon had sworn them to both Louis XVI and the Republic.)

At Fontainebleau, Napoleon considered his dwindling options. His own preference was still to march on Paris, but Maret, Savary, Caulaincourt, Berthier, Macdonald, Lefebvre, Oudinot, Ney and Moncey were uniformly opposed, though Ney never spoke to the Emperor in the bald, rude terms later ascribed to him;92 some of them favoured joining the Empress at Blois. It was paradoxical that although the marshals hadn’t forced abdication on Napoleon after he had been comprehensively beaten in Russia in 1812, nor after Leipzig in 1813, they did favour it when he was still winning victories in 1814, albeit with an army that was heavily outnumbered. They pointedly reminded him of his repeated statements only to do what was in the best interest of France.93 Napoleon suspected that they wanted him to abdicate in order to protect and enjoy the chateaux and riches he had given them, and gave voice to this opinion in bitter moments.

Although he had asked some of them – Macdonald, Oudinot and especially Victor – to do the impossible in 1814, and had berated them when they could achieve only the extraordinary, the real explanation for their behaviour wasn’t selfish, but rather that none could see how the campaign could possibly be won from the strategic position they were in, even if it were continued from the French interior. Since Napoleon’s abdication was the only way the war could end, it was logical for them to call for it, albeit respectfully. However much Napoleon reviewed the Old Guard and other units, who on April 3 shouted ‘Vive l’Empereur!’ at the idea of marching on Paris, the marshals knew that the numbers simply no longer added up – insofar as they ever had during this campaign.94Macdonald stated in his memoirs that he didn’t want to see the capital go the way of Moscow.95 Ney and Macdonald had wanted Napoleon to abdicate immediately so that a regency might be salvaged from the wreckage, and Napoleon sent them and Caulaincourt to Paris to see if this was still possible. However, on April 4 Marmont marched his corps straight into the Allied camp to capitulate, along with all their arms and ammunition. This led the Tsar to demand Napoleon’s unconditional abdication.96Alexander had taken his huge army right across Europe and nothing less would now do.

For the rest of his life, Napoleon went over the circumstances of Marmont’s treachery again and again. Marmont was, he said, with slight but pardonable exaggeration, ‘a man whom he had brought up from the age of sixteen’.97 For his part, Marmont said Napoleon was ‘satanically proud’, as well as given to ‘negligence, insouciance, laziness, capricious trust and an uncertainty as well as an unending irresolution’.98 Napoleon was certainly proud, definitely not lazy, and if he was capriciously trusting, the Duc de Ragusa had been a prime beneficiary. ‘The ungrateful wretch,’ Napoleon said, ‘he will be more unhappy than me.’ The word ragusard was adopted to mean traitor, and Marmont’s old company in the Guard was nicknamed ‘Judas company’. Even three decades later, when he was an old man living in exile in Venice, children used to follow him about, pointing and shouting, ‘There goes the man who betrayed Napoleon!’99