Hoist up your sails of silk

And flee away from each other.

![]()

“HE’S A BRILLIANT MADMAN born a century too soon,” Assemblyman Newton M. Curtis complained, escaping from Theodore Roosevelt’s suite in the Delavan House, Albany.1 Mad or not, Roosevelt had been returned to serve a third term in the New York State Legislature, and was again a candidate for Speaker. With less than twenty-four hours to go before the Republican New Year’s Eve caucus, his nomination seemed almost certain.2 This time the honor would not be complimentary, for his party had recaptured both houses of the legislature with large majorities.3 To be nominated on 31 December 1883 was to step automatically into the Chair next morning.

Few Assemblymen agreed with Curtis as to Roosevelt’s precocity. The novelty of his extreme youth had long since worn off. If he had been a competent party leader at twenty-four, why not Speaker at twenty-five? The candidate himself might be forgiven for thinking that his time for real power had come. All political trends, citywide, statewide, and nationwide, were in his favor. New York State’s would-be Republican boss, Senator Warner (“Wood-Pulp”) Miller, had cautiously embraced such Rooseveltian principles as municipal reform, purified electoral procedures, and the elimination of unelected political middlemen. At the gubernatorial level, Grover Cleveland had publicly split with Tammany Hall, pledging an independent stance for the rest of his administration. He would obviously like to collaborate with a Speaker as independent as Roosevelt. And in Washington even President Arthur had proved to be surprisingly enlightened. That so notorious a machine politician should now be espousing the cause of Civil Service Reform, and vetoing pork-barrel legislation on moral grounds, must have made Roosevelt think ruefully of the days when “Chet” Arthur, as his father’s rival for the Collectorship of New York, had symbolized everything Theodore Senior despised. It was due largely to the President’s popularity and undeniable decency that the Republican party had recovered from the humiliations of 1882, and stood a good chance of retaining the White House in 1884.4

“There is a curse on this house.”

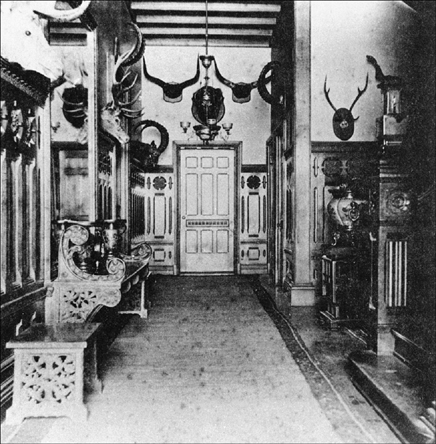

Hallway of the Roosevelt mansion at 6 West Fifty-seventh Street, New York City. (Illustration 9.1)

There is no doubt that Roosevelt passionately wanted to be Speaker. If nominated, he would become the number two elected officer in the nation’s number one state—and would play a vital role in what promised to be one of the most exciting election years in American history. As 1883 drew to a close, President Arthur himself was reported to be following events in Albany with anxious interest.5

![]()

ROOSEVELT HAD BEEN campaigning hard since November. Within days of his reelection, he had dispatched a series of characteristically terse letters to Assemblymen-elect:

Dear Sir: Although not personally acquainted with you, I take the liberty of writing to state that I am a candidate for Speaker. Last year, when we were in the minority, I was the party nominee for that position; and if you can consistently support me I shall be greatly obliged.6

To one correspondent, who requested further information, Roosevelt sent a self-description that combined, in one sentence, the words “Harvard,” “Albany,” and “Dakota,” along with the ringing declaration, “I am a Republican, pure and simple, neither a ‘half breed’ nor a ‘stalwart’; and certainly no man, nor yet any ring or clique, can do my thinking for me.”7

He followed up many of these letters with personal visits, probing into remote corners of New York State in search of rural supporters. Where he could not go by train, he traveled by buggy; where there were no buggies, he went on foot. Late one evening he arrived at a farm in Monroe County and found his prospect not at home. Undeterred, Roosevelt tramped for miles along the road to Scottsville, hailing every rig that loomed out of the darkness: “Hi, there, is this Mr. Garbutt?” Eventually his persistence was rewarded. He secured not only a vote but a lift back to the station.8

![]()

IT MAY BE WONDERED why Roosevelt should have to campaign so strenuously for an office to which he was surely entitled, having been Minority Leader in the session of 1883. But at that time the New York Legislature made no such guarantees. There was, besides, serious opposition within his own party. At the state Republican convention in September, Senator Miller had rather rashly promised the job to somebody else—a retired Assemblyman in Herkimer County named Titus Sheard. The constituency had fallen to the Democrats in recent years, and Miller, wishing to do something dramatic to strengthen his leadership, asked Sheard to help him pull Herkimer County “out of the mire.” The Senator promised that if Sheard, a respected local citizen, would run for election again—and win—he would be rewarded with the Speakership.9 Sheard had fulfilled his part of the bargain.

Once again, Roosevelt found himself pitted against the party organization. A Herald editorial described the race as a contest between “the young and the good” and “the old and the bad,” although most observers agreed that Titus Sheard would make an excellent Speaker, if nominated. Roosevelt, on the other hand, was embarrassed by the endorsement of some anti-Miller Stalwarts in New York—local bosses like John J. O’Brien, Jake Hess, and Barney Biglin. Although he did not like these men, they had considerable political weight, and he could not afford to throw them off. “The frisky Roosevelt colt is showing some mettle,” wrote the Sun in an article entitled “Candidates’ Handicap,” “… but he is not so well in hand [as Titus Sheard] and is likely to break on the home stretch.”10

On the contrary, his lead steadily increased right through the last day of the campaign. There was a momentary setback when Isaac Hunt, of all people, treacherously deserted him in favor of the third-running candidate, George Z. Erwin. Another candidate, Billy O’Neil, compensated for this by withdrawing and pledging his own votes to Roosevelt. Then, at 5:00 P.M. on 31 December, Erwin also agreed to withdraw (much to the embarrassment of Hunt, who in later life insisted he had been “for Teddy” all along). With the caucus only three hours away, Roosevelt seemed assured of enough votes to win on the first ballot.11

Assemblyman Curtis had already found Roosevelt almost “mad” with the excitement of possible victory. If so, one can only guess at his reaction when the news of Erwin’s withdrawal came in from spies down the corridor. But three hours is not too short a time in politics for triumph to collapse into defeat. Roosevelt’s Stalwart backers were hastily summoned by Senator Miller, who promised them certain “valuables in the treasury” if they would switch their votes to Sheard.12 The boss’s reputation was at stake, and his bribe was so large as to seduce the entire New York City delegation at once. Roosevelt was still reeling from this blow when the last remaining candidate, DeWitt Littlejohn, also switched to Sheard. By the time Roosevelt trudged up the hill to the caucus room shortly before eight o’clock, it was evident that he was a beaten man. “Mr. Roosevelt had an older and less buoyant look than usual when he dropped wearily into his seat,” wrote the Sun correspondent. “He has seen a great deal of human nature during the past week, and isn’t particularly in love with a public career at present. He made a handsome exit as a candidate in a manly speech, however, and his vote [30 to Sheard’s 42] was something to be proud of.”13

With a graceful final gesture, Roosevelt made the nomination of Titus Sheard unanimous.14 The caucus broke up, and the tensions of weeks of campaigning dissolved into friendly backslapping and compliments of the season. Some time later the church bells of Albany announced the arrival of 1884. Meanwhile, far away in New York, the World’s presses were drumming out thousands upon thousands of times the ominous sentence, “This will not be a Happy New Year to the exquisite Mr. Roosevelt.”15

![]()

HE WAS PRIVATELY so “chagrined” by his defeat (and by the added annoyance of drawing the second-last seat in the House, on the extreme back row of the northern tier) that his weary, aged look persisted for days. But as the session proceeded, his mood began to improve. He realized that far from being weakened by failure, he was now a more potent political force than ever. “The fact that I had fought hard and efficiently … and that I had made the fight single-handed, with no machine back of me, assured my standing as floor leader. My defeat in the end materially strengthened my position, and enabled me to accomplish far more than I could have accomplished as Speaker.”16 Titus Sheard was deferential to his young challenger, and offered him carte blanche in choosing his committee appointments. Roosevelt suggested three: Banks, Militia, and the powerful Cities Committee, of which he was promptly made chairman. Testing his newfound strength, he objected to the clerk Sheard had put under him, and after a short struggle the Speaker capitulated. Roosevelt Republicans were placed in control of all the other important committees. Their exultant leader declared that “titular position was of no consequence … achievement was the all-important thing.”17

He threw himself with zest back into legislative business, working up to fourteen hours a day. Every morning, to speed up his metabolism, he indulged in half an hour’s fierce sparring with a young prizefighter in his rooms.18 “I feel much more at ease in my mind and better able to enjoy things since we have gotten under way,” he wrote Alice on 22 January. “I feel now as though I had the reins in my hand.” Reading this letter over, he added a discreet postscript: “How I long to get back to my own sweetest little wife!”19

![]()

THE TRUTH IS that Alice, now in her ninth month of pregnancy, was feeling lonely and somewhat neglected.20 No sooner had her husband returned from Dakota, and hung up his buffalo-head, than he had plunged into the campaign for reelection; immediately afterthat, he plunged into the Speakership contest. Since 26 December she had seen him only on weekends; even these, now, were being eroded with work and political entertaining.

To avoid having Alice alone at such a time, Roosevelt sublet their brownstone and installed her at 6 West Fifty-seventh Street.21 Corinne Roosevelt Robinson, who had recently had a baby herself, moved in for a temporary stay at about the same time. The two young women planned to run a nursery for both children on the third floor. With Mittie and Bamie also in residence, Alice was not short of feminine company—nor for affection, since all three women adored her.22 Yet she obviously longed for the lusty male presence of her spouse. Whenever he arrived from Albany, Alice was waiting at the door. “Corinne, Teddy’s here,” she would shout happily up the stairs. “Come and share him!”23

Alice Lee Roosevelt was now twenty-two and a half years old. Even at this extreme stage of her pregnancy, she was still, by more than one account, “flower-like” in her beauty.24 Such politicians whom Roosevelt brought home for the weekend were loud in praise of her afterward.25 Roosevelt himself remained as naively in love with Alice as he had been in Cambridge days. “How I did hate to leave my bright, sunny little love yesterday afternoon!” he wrote on 6 February. “I love you and long for you all the time, and oh so tenderly; doubly tenderly now, my sweetest little wife. I just long for Friday evening when I shall be with you again …”26

However cloying his love-talk, however reminiscent his attitude of David Copperfield’s to the “child-wife” Dora, Alice Lee was still, after three years and three months of marriage, his “heart’s dearest.”27

![]()

ROOSEVELT HAD PROMISED the electorate that his main concern in the session of 1884 would be to break the power of the machines, both Republican and Democratic, in New York City.28 As chairman of the Committee on Cities, he was now in a position to push through some really effective legislation. Accordingly he wasted no time getting down to business. “He would go at a thing as if the world was coming to an end,” said Isaac Hunt.29 On 11 January, three days after his appointment, he introduced three antimachine bills in the Assembly. The first proposed a sharp increase in liquor license fees; the second proposed a sharp decrease in the amount of money the city could borrow from unorthodox sources; the third proposed that the Mayor be made simultaneously much more powerful and much more accountable to the people.30

It was a foregone conclusion that the liquor license bill would fail, even though Roosevelt had now developed great influence in the Assembly. (The alliance between government and malt, in the late nineteenth century, was as unbreakable as that between government and oil in the late twentieth.) Still, he emerged with his reputation as a crusader enhanced, while in no way sounding like a prohibitionist. Any such image would be fatal to a politician living on so notoriously thirsty an island as Manhattan, with its huge, tankard-swinging German population. “Nine out of ten beer drinkers are decent and reputable citizens,” Roosevelt declared. “That large class of Americans who have adopted the German customs in regard to drinking ales and beers … are in the main … law-abiding.”31

Roosevelt’s second measure achieved passage, and added a needed touch of fiscal discipline to the New York treasury. The third, which he rightly regarded as the most important piece of legislation in the session of 1884, won tremendous popular support—and opposition in the Assembly to match. Grandly entitled “An Act to Center Responsibility in the Municipal Government of the City of New York,” it consisted of a mere forty words; but these words, if they became law, were enough to make political eunuchs of the city’s twenty-four aldermen. At the moment it was the Mayor who was the eunuch, since the Board of Aldermen enjoyed confirmatory power over all his appointments. Defenders of the status quo invoked the Jeffersonian principle that minimum power should be shared by the maximum number of people.32 Roosevelt, whose contempt for Thomas Jefferson was matched only by his worship of the autocratic Alexander Hamilton, believed just the opposite. He pointed out that New York’s aldermen were, almost to a man,“merely the creatures of the local ward bosses or of the municipal bosses.”33 It was the machine, therefore, which ultimately governed the city; and Roosevelt did not consider that democratic.

His major speech in support of the mayoralty bill, when it came up for a second hearing on 5 February, was so forceful as to create an instant sensation. Roosevelt himself considered it “one of my best speeches,”34 and the press agreed with him. A sampling of next day’s headlines tells the story:

ROOSEVELT ON A RAMPAGE

Whacking the Heads off Republican

Office-Holders in This City

MR. ROOSEVELT’S HARD HITS

Making a Lively Onslaught on New York’s Aldermen

TAMMANY DEFEATED

Mr. Roosevelt’s Brilliant Assault on Corruption35

The speech, as transcribed in black and white by Albany correspondents, loses much of the color which Roosevelt undoubtedly gave it in delivery, for he was by now an accomplished, if awkward, orator. Privately he admitted that “I do not speak enough from the chest, so my voice is not as powerful as it ought to be.”36 Like a violinist without much tone, he had learned to compensate with agogic accents (“Mister Spee-KAR!”), measured phrasing, and percussive noise-effects. Observers noticed his habit of biting words off with audible clicks of the teeth,37 making his syllables literally more incisive.

One sound in which Roosevelt specialized—and which traveled very well in the cavernous Assembly Chamber—was the plosive initial p. He made full use of it in this speech, and since he stood in the back row, one can only feel sorry for the Assemblymen in his immediate vicinity.

“I will ask the particular attention of the House to this bill,” said Roosevelt. “It simply proposes that the Mayor of the City of New York shall have absolute power in making appointments … At present we have this curious condition of affairs—the Mayorpossessing the nominal power and two or three outside men possessing the real power. I propose to put the power in the hands of the men the people elect. At present the power is in the hands of one or two men whom the people did not elect.”38

Roosevelt’s speech, however, was remarkable for more than alliteration—although the ps popped energetically to the end. His arguments in favor of an all-powerful Mayor, independent of and unanswerable to the city’s two dozen shadowy aldermen, were, to quote The New York Times, “conclusive.”39 In reply to criticism that he wished to create “a Czar in New York,” Roosevelt said simply, “A czar that will have to be reelected every second year is not much of an autocrat.” In any case, he went on, “I would rather have a responsible autocrat than an irresponsible oligarchy.” New York’s “contemptible” aldermen, whom scarcely any citizen could name, were “protected by their own obscurity.” But the Mayor, by virtue of his office, “stands with the full light of the press directed upon him; he stands in the full glare of public opinion; every act he performs is criticized, and every important move that he makes is remembered.”40

Reporters noted with approval that Roosevelt had lost his youthful tendency to ascribe all evil to the Democratic party. His remarks on municipal corruption were ruthlessly non-partisan. The four aldermen whom he chose to name as vote-sellers to Tammany Hall were all Republicans. “They have made themselves Democrats for hire,” said Roosevelt in tones of disgust. “If public opinion does its work effectively … no one of them would ever be returned to any office within the gift of the people.” He concluded with the extraordinary statement that he did not care if the passage of his bill removed every Republican officeholder from the municipal government—“the party throughout the state and nation would be benefited rather than harmed.”41

Reading between the lines of this speech, one senses a fierce desire for revenge upon the Republican city bosses who betrayed him when he was about to win the Speakership. Subconsciously, no doubt, Roosevelt was himself mounting that autocratic pedestal, to bask “in the full glare of public opinion,” while men like O’Brien, Hess, and Biglin skulked in the shadows of “their own obscurity.” Consciously, however, he was sincere in his arguments, and it was generally agreed that what he said made good sense. Rising to reply, the House’s ranking Democrat, James Haggerty, admitted that the moral character of New York aldermen was low. His objection to Roosevelt’s measure involved “a question of principle.”42 Jeffersonian arguments followed. The debate lasted all day, and, in spite of desperate lobbying by Tammany Hall, ended with a complete rout of the opposition. “The Roosevelt Bill,” as it would henceforth be called, was ordered engrossed for a third reading.

![]()

NOT CONTENT WITH his three municipal reform bills, Roosevelt simultaneously pushed for an investigation of corruption in the New York City government. This resolution was nothing new. Probes had been launched routinely in the past, and as routinely thrown off by the city’s smoothly spinning machine.43 But Roosevelt felt sure that if he were put in charge of his own investigation, he would be able to jam at least some of the levers. Permission was granted almost immediately by the Assembly. It could not very well have refused, because venality, inefficiency, and waste in New York had again become a national scandal, and an embarrassment to both Democrats and Republicans in this presidential election year. On 15 January Roosevelt found himself chairman of a Special Committee to Investigate the Local Government of the City and County of New York. His colleagues consisted of two Roosevelt Republicans and two sympathetic Democrats, giving him, in effect, a free hand to choose his own witnesses and write his own report.44

The committee’s hearings began four days later, at the Metropolitan Hotel in New York. Roosevelt symbolically opened the proceedings by calling for a Bible, and in the same breath, for Hubert O. Thompson, Commissioner of Public Works. As a freshman Assemblyman, he had been both repelled and fascinated by Thompson, who seemed to spend most of his time in Albany, and was the successful machine politician par excellence. “He is a gross, enormously fleshy man,” Roosevelt wrote then, “with a full face and thick, sensual lips; wears a diamond shirt pin and an enormous seal ring on his little finger. He has several handsome parlors in the Delavan House, where there is always champagne and free lunch; they are crowded from morning to night with members of assembly, lobbyists, hangers-on, office holders, office seekers, and ‘bosses’ of greater or less degree.”45 For the last two years Roosevelt had looked on in dismay while Thompson’s department more than doubled its expenditures, without any noticeable increase in services.46 He had no doubt that much of the money was flowing directly into Thompson’s pockets.

Now the two men faced each other directly across a rectangular table, and Roosevelt plunged at once into his investigation. But for all the young man’s “sharp looks” and energy, it was evident to reporters that he was feeling his way. Thompson, a veteran of many investigations, handled him easily. No sooner had Roosevelt asked his first formal questions than the door opened and a messenger came in with a telegram for the witness. Thompson scanned it, laughed, then read it aloud to the committee. It was a summons to appear at an identical investigation, being conducted simultaneously by the Senate.

“Can I telephone that I am coming down?” he asked.

“Certainly,” said Roosevelt, nonplussed. With barely veiled insolence, Thompson turned to the messenger.

“Tell them I will leave here in five minutes,” he said, and sat back to enjoy the general laughter at Roosevelt’s expense.47

![]()

ROOSEVELT WAS FORCED to turn his attention to other areas of corruption, but they were so various, and his witnesses so infallible in their pleas of bad memory and reasons for non-appearance, that the investigation languished for several sessions without uncovering any important evidence. He began to fume with frustration, and on 26 January, when the city sheriff suggested a question regarding transportation costs was “going into a gentleman’s private affairs,”48 his anger exploded, and he shot forth a fusillade of angry ps.

“You are a public servant,” Roosevelt shouted, thumping the table. “You are not a private individual; we have a right to know what the expense of your plant is; we don’t ask for the expense of your private carriage that you use for your own conveyance; we ask what you, a public servant, pay for a van employed in the service of the public; we have a right to know; it is a perfectly proper question!”49

The sheriff meekly supplied the information. But at a subsequent hearing, on 2 February, he was so shocked by the chairman’s request to state “how much his office had cost him” that he again pleaded privacy. “This offer threw Mr. Roosevelt into a white heat of passion,” reported the World, “and he declared that the answer must be given. The Sheriff showed no disposition to reply, and his counsel puffed serenely on his cigar.” Roosevelt was forced to accept that the question had indeed been indiscreet, and it took a fifteen-minute recess for him to calm down.50 Experiences like this disciplined his interrogative technique, and he soon became more effective.

On Monday 11 February the sheriff reluctantly yielded up his books for inspection. Beaming with delight, Roosevelt announced that the committee would stand adjourned for a week, while counsel audited these records.51

![]()

HE HAD ANOTHER, more private reason for declaring an adjournment. Alice’s baby was due at any moment. With luck, the child would be born on Thursday, 14 February—St. Valentine’s Day, and the fourth anniversary of the announcement of his engagement. The prospect of such a coincidence was apparently enough to reassure him that there was time for a quick trip to Albany, to see how “the Roosevelt Bill” was doing.

What Alice thought of this desertion on the eve of her first confinement is not recorded, but she could hardly have been pleased—particularly as Corinne was away, and Mittie was in bed with what seemed to be a heavy cold.52 That left only Bamie in the house to take care of both of them. But with the family doctor in attendance, Mr. and Mrs. Lee installed in the Brunswick, and Elliott only a few blocks away, her husband was not over-concerned. On Tuesday, 12 February, he caught an express train to the capital.

![]()

IT WAS A RELIEF for an asthmatic man to get out of New York that morning. For over a week the city had been shrouded in a chill, dense, dripping mist. No wonder Mittie had caught cold. Longshoremen were calling it the worst fog in twenty years.53 What little light seeped out of streetlamps and shop windows diffused into a universal gray that one reporter compared to the limbo before the Creation. With no sun or stars to pierce the fog (for the skies, too, were veiled) it was difficult to distinguish dawn from dusk, except through the blind comings and goings of half a million workers. Train service was reduced to an absolute minimum, and river traffic canceled but for a few ferries feeling their way past each other. Bridges were jammed with groping multitudes. The all-pervading vapor muffled New York’s customary noise to an uneasy murmur, broken only by the hoarse calls of fog-whistles, and the occasional shriek of a woman having her furs torn off by invisible hands. Every brick and metal surface was slimy to the touch; sticky mud covered the streets; the air smelled of dung and sodden ashes. Meteorologists predicted yet more “cloudy, threatening weather,”54 and a New York Times editor wrote despairingly, “It does not seem possible that the sun will ever shine again.”55

Roosevelt found the weather in Albany clearer, if equally humid, for the entire Eastern seaboard was dominated by a fixed low-pressure system. The Assembly’s magnificent fresco The Flight of Evil Before Good was beginning to blister, and occasional flakes fell off in the saturated air. Whether from damp rot, or some more fundamental fault, the vaulted ceiling of the chamber was showing ominous cracks, and nervous Assemblymen had taken to walking around, rather than under, its three-ton keystone.56

However it would take more than a low-pressure system to affect Roosevelt’s natural good humor that Tuesday. With 330 pages of testimony already taken by his Investigative Committee, and the prospect of sensational revelations in the weeks that lay ahead, he was again making front-page headlines. His bill was sure of passage, and (if Alice managed to hold out until Thursday) he would be able personally to guide it through the House on Wednesday afternoon. To speed it on its way through the Senate, a mass meeting of citizens had been called in New York’s Cooper Union on Thursday evening.57 The guest-list was to be a brilliant one: General U. S. Grant himself had agreed to serve as vice-president. All this could only enhance the stature of the Honorable Gentleman from the Twenty-first.

Things were certainly going well for Roosevelt now. He had shed his sophomoric tendencies, along with his side-whiskers, a good while back. The newspapers which had treated him so condescendingly in the past were now uniformly respectful, even admiring, in their tone. Republicans in the House regarded him as their leader de ipse; some of the more worshipful members put boutonnieres on his desk every morning. He, for his part, no longer felt snobbish toward his humbler colleagues; on the contrary, he rejoiced in his ability to work “with bankers and bricklayers, with merchants and mechanics, with lawyers, farmers, day-laborers, saloon-keepers, clergymen, and prize-fighters.”58 Except for occasional flare-ups of aggressive temper (“You damned Irishman, what are you telling around here, that I am going to make you an apology? … I’ll break every bone in your body!”),59 he was as a rule well-mannered and charming, and, when he chose to be, deliciously comic. Even the melancholy Isaac Hunt took pleasure in his wit. “Through it all and amid it all that humorous vein in him! You would be talking with him and he would strike that falsetto. He did that all the while … he was awful funny.” Unlike most comedians, Roosevelt also found other people’s jokes amusing, and the Assembly Chamber rang often with his honest, high-pitched laughter.60

He was never bored, and found entertainment in the dullest moments of parliamentary debate. With a writer’s eye and ear, he noted down incidents and scraps of Irish dialogue for future publication. There was Assemblyman Bogan, who “looked like a serious elderly frog,” standing up to object to the rules, and, on being informed that there were no rules to object to, moving “that they be amended until there are-r-e!”61 There was the member who accused Roosevelt, during a legal debate, of occupying “what lawyers would call a quasi-position on the bill,” only to be crushed by another member rising majestically in his defense: “Mr. Roosevelt knows more law in a wake than you do in a month; and more than that, Michael Cameron, what do you mane by quoting Latin on the floor of the House when you don’t know the alpha and omayga of the language?”62

He was a connoisseur of mixed metaphors, in which Assembly debate was rich, and took great delight in analyzing them. Of one Democrat’s remark that convict labor “was a vital cobra which was swamping the lives of the laboring men,” Roosevelt wrote:

Now, he had evidently carefully put together the sentence beforehand, and the process of mental synthesis by which he built it up must have been curious. “Vital” was, of course, used merely as an adjective of intensity; he was a little uncertain in his ideas as to what a “cobra” was, but took it for granted that it was some terrible manifestation of nature, possibly hostile to man, like a volcano, or a cyclone, or Niagara, for instance; then “swamping” was chosen as an operation very likely to be performed by Niagara, or a cyclone, or a cobra; and behold, the sentence was complete.63

Perhaps the best of Roosevelt’s Albany stories is his account of the committee meeting whose chairman, having “looked upon the rye that was flavored with lemon peel,” fell asleep during a long piece of testimony, and, on waking up, gaveled the witness to order, on the grounds that he had seen him before: “Sit down, sir! The dignity of the Chair must be preserved! No man shall speak to this committee twice. The committee stands adjourned.”64

![]()

AT THE BEGINNING of the morning session of the House on Wednesday, 13 February, Assemblymen were seen flocking around Theodore Roosevelt and shaking his hand.65 He had just received a telegram from New York, stating that Alice had given birth to a baby girl late the night before. The mother was “only fairly well,”66 but that was to be expected after the agonies of a first delivery. Roosevelt proudly accepted a father’s congratulations and requested leave of absence, to begin after the passage of his other bill that afternoon. “Full of life and happiness,” he proceeded to report fourteen other bills out of his Cities Committee.67 Joy, evidently, must not be allowed to interfere with duty.

Several hours later, a second telegram arrived, and as he read it his face changed. Looking suddenly “worn,” he rushed to catch the next train south.68 No word remains as to the text of the telegram, but it undoubtedly contained a gentler version of the news that Elliott had just given to Corinne at the door of 6 West Fifty-seventh Street: “There is a curse on this house. Mother is dying, and Alice is dying too.”69

![]()

WITH INEXORABLE SLOWNESS, the train crawled down the Hudson Valley into thickening fog. Even in clear weather, the 145-mile journey took five hours; it was anybody’s guess how long it would take on this murky evening. There was nothing Roosevelt could do but read and reread his two telegrams, and summon up all his self-discipline against that unmanly emotion, panic. Six years ago last Saturday he had taken another such express to New York, in response to another urgent telegram, and arrived to find his father dead.… For hour after hour the locomotive bell tolled mournfully in the distance ahead of him.70 It was about 10:30 P.M. when the train finally pulled into Grand Central Station. Roosevelt had to search out West Fifty-seventh Street by the light of lamps that “looked as though gray curtains had been drawn around them.”71 When he reached home the house was dark, except for a glare of gas on the third floor.

![]()

ALICE, DYING OF Bright’s disease, was already semicomatose as Roosevelt took her into his arms. She could scarcely recognize him, and for hours he sat holding her, in a vain effort to impart some of his own superabundant vitality. Meanwhile, on the floor below, Mittie was expiring with acute typhoid fever. The two women had become very close in recent years; now they were engaged in a grotesque race for death.

Bells down Fifth Avenue chimed midnight—St. Valentine’s Day at last—then one, then two. A message came from downstairs: if Theodore wished to say good-bye to his mother he must do so now. At three o’clock, Mittie died. She looked as beautiful as ever, with her “moonlight” complexion and ebony-black hair untouched by gray.72 Gazing down at her, Roosevelt echoed his brother’s words: “There is a curse on this house.”73 In bewildered agony of soul, he climbed back upstairs and again took Alice Lee into his arms.

Day dawned, but the fog outside grew ever thicker, and gaslight continued to burn in the Roosevelt mansion. About mid-morning, a sudden, violent rainfall miraculously cleared the air, and for five minutes the sun shone on muddy streets and streaming rooftops. The weather seemed about to break, but clouds closed over the city once more. By noon the temperature was 58 degrees, and the humidity grew intolerable. Then, slowly, the fog began to lift, and dry cold air blew in from the northeast. At two o’clock, Alice died.74

![]()

ROOSEVELT DREW a large cross in his diary for 14 February, 1884, and wrote beneath: “The light has gone out of my life.”

![]()

THAT EVENING, Cooper Union was packed with thousands of citizens supporting the “Roosevelt Bill,” whose passage through the Assembly had been postponed pending his return. Reporters noticed that the “more than usually intelligent audience” included, besides General Grant, ex-Mayor Grace, Professor Dwight, Elihu Root, Chauncey Depew, and two of Roosevelt’s uncles, James and Robert. The latter must have known about Theodore’s double tragedy, but they kept silent, for the news would not be announced until morning.

Although the real hero of the evening was not there, the hall resounded with cheers at the mention of his name. “Whatever Theodore Roosevelt undertakes,” declared Douglass Campbell, the keynote speaker, “he does earnestly, honestly, and fearlessly.” The resolution in support of the bill was approved by a tremendous, air-shaking shout of “AYE!”75

![]()

“SELDOM, IF EVER, has New York society received such a shock as yesterday in [these] sad and sudden deaths,” the World commented on 15 February. “The loss of his wife and mother in a single day is a terrible affliction,” agreed the Tribune, “—it is doubtful whether he will be able to return to his labors.” The Herald, while equally sympathetic to the bereaved Assemblyman, dwelt more on the qualities of the deceased. Mittie was praised for her “brilliant powers as leader of a salon,” and for her “high breeding and elegant conversation.” Alice, said the paper, “was famed for her beauty, as well as many graces of the heart and head.”76

In Albany, the House of Assembly paid an unprecedented tribute to its stricken member by declaring unanimously for adjournment in sympathy. Seven speakers, some of them in tears, eulogized the dead women and paid tribute to Roosevelt. “Never in my many years here,” declared a senior Democrat, “have I stood in the presence of such a sorrow as this.” He said that Alice had been a woman so blessed by nature as to be “irresistible” to any man she chose to love. The House’s resolution, adopted by a rising vote, spoke of the “desolating blow” that had struck “our esteemed associate, Hon. Theodore Roosevelt,” and expressed the hope that its gesture would “serve to fortify him in this moment of his agony and weakness.”77

![]()

MORE TEARS WERE SHED at the funeral on Saturday, 16 February, in the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church. The sight of two hearses outside the door, and two rosewood coffins standing side by side at the altar, was too much for many members of the large and distinguished congregation.78 Sobs could be heard throughout the simple service. The minister, Dr. Hall, could hardly control his voice as he compared the sad but unsurprising death of a fifty-year-old widow with the “strange and terrible” fate that had snatched away a twenty-two-year-old mother. He cried openly as he prayed for “him of whose life she has been so great a part.”79

Through all these tears, Roosevelt sat white-faced and expressionless. He had to be handled like a child at the burial ceremony in Greenwood Cemetery.80 “Theodore is in a dazed, stunned state,” wrote Arthur Cutler, his ex-tutor, to Bill Sewall in Maine. “He does not know what he does or says.”81

![]()

THE SHOCK UPON Roosevelt of Alice’s wholly unexpected death, coming at a time when he had been “full of life and happiness,” was so violent that it threatened to destroy him. Mittie’s death served only to increase his bewilderment. He seemed unable to understand the condolences of friends, showed no interest in his baby, and took to pacing endlessly up and down his room. The family were afraid he would lose his reason.82

Actually he was in a state of cataleptic concentration on a task which now preoccupied him above all else. Like a lion obsessively trying to drag a spear from its flank, Roosevelt set about dislodging Alice Lee from his soul. Nostalgia, a weakness to which he was abnormally vulnerable, could be indulged if it was pleasant, but if painful it must be suppressed, “until the memory is too dead to throb.”83

With the exception of two brief, written valedictories to Alice—one private, one for limited circulation among family and friends—there is no record of Roosevelt ever mentioning her name again.84 The first of these memorials was entered into his diary a day or two after the funeral:

Alice Hathaway Lee. Born at Chestnut Hill, July 29th 1861. I saw her first on October 18th 1878; I wooed her for over a year before I won her; we were betrothed on January 25th 1880, and it was announced on Feb. 16th;85 on Oct. 27th of the same year we were married; we spent three years of happiness greater and more unalloyed than I have ever known fall to the lot of others; on Feb 12th 1884 her baby was born, and on Feb. 14th she died in my arms; my mother had died in the same house, on the same day, but a few hours previously. On Feb 16th they were buried together in Greenwood … For joy or sorrow, my life has now been lived out.86

There were one or two oblique, involuntary references to Alice in conversation during the months immediately following her death, but before the year was out his silence was total. Ironically, the name of another Alice Lee—his daughter—was sometimes forced through his lips, but even this was quickly euphemized to “Baby Lee.” Although the girl grew to womanhood, and remained close to him always, he never once spoke to her of her mother.87 When, as ex-President, he came to write his Autobiography, he wrote movingly of the joys of family life, the ardor of youth, and the love of men and women; but he would not acknowledge that the first Alice ever existed.

Others close to Roosevelt naturally took on the same attitude. After his death, their hands went methodically through his correspondence, and all love-letters between himself and Alice—with four trivial exceptions—were destroyed. Whole pages of his Harvard scrapbook, presumably containing souvenirs of their courtship and marriage, were snipped out. Photographs of Alice were torn out of their paper frames. Here and there, handwritten captions that doubtless referred to her are erased so fiercely the page is worn into holes.88 Only by some miracle did five private diaries, and a handful of letters written to friends, survive to testify to his love for the yellow-haired girl from Chestnut Hill.

![]()

IT IS NOW WELL OVER A CENTURY since Alice Hathaway Lee married Theodore Roosevelt, gave birth to his child, and died. Little more than the few facts recorded in this volume will likely ever be known of her. She was, after all, only twenty-two and a half years old at the end. The Roosevelt family, on first meeting her, had found her “attractive but without great depth.”89 She seemed too simple for such a complex person as Theodore. After her death, however, they claimed to have noticed that “abilities lay beneath the surface.”90 Their first, unsentimental impression was surely the more trustworthy.

Only one woman ventured to suggest, many years later, that Alice, had she lived, would have driven Roosevelt to suicide from sheer boredom.91 The bitterness of this remark is understandable, since it was made by Alice’s successor; but one suspects there may be a grain of truth in it. Alice does indeed seem to have been rather too much the classic Victorian “child-wife,” a creature so bland and uncomplicated as to be incapable of spiritual growth. Her few surviving letters are sweetly phrased and totally uninteresting. Roosevelt, whose own growth, both physical and mental, was so abnormally paced, could not have been happy married to an aging child.

In his published memorial to Alice, Roosevelt—echoing Dr. Hall—spoke of the “strange and terrible fate” that took her away. Strange, maybe—yet perhaps more kind than terrible. In quitting him so early, she rendered him her ultimate service. In burying her, he symbolically buried his own lingering naïveté. At the time, of course, he felt that he was burying all of himself.