Thus came Olaf to his own,

When upon the night-wind blown

Passed that cry along the shore;

And he answered, while the rifted

Streamers o’er him shook and shifted,

“I accept thy challenge, Thor!”

![]()

BABY LEE WAS CHRISTENED on Sunday, 17 February 1884, the day after the funeral, and placed in care of Bamie.1 The latter, now in her thirtieth year, seemed irrevocably headed for spinsterdom, and her sudden acquisition of a golden-haired infant was the only happy event of that bitter weekend. Having thus, within twenty-four hours, interred the past and anointed the future, the Roosevelts addressed themselves to the present.

For all Cutler’s statement that Theodore was “in a dazed, stunned state” on Saturday, there is a tough decisiveness about the family’s actions during the period immediately following that could only have emanated from him. He set the tone by announcing that he would go back to work at once. “There is nothing left for me except to try to so live as not to dishonor the memory of those I loved who have gone before me.”2

“Mr. Roosevelt, I’m going to veto those bills!”

Governor Grover Cleveland by Eastman Johnson. (Illustration 10.1)

With Alice and Mittie dead, Theodore returning to Albany, and Corinne and Elliott already thinking of moving to the country, it was plain that 6 West Fifty-seventh Street must be sold. The Roosevelt mansion had become increasingly expensive to maintain over the years. Mittie’s lavish soirées, receptions, banquets, and balls, complete with orchestras and liveried footmen, had considerably eroded the family fortune.3 Bamie, in her new capacity as surrogate mother, no longer had the time nor the money to keep open house for Astors and Vanderbilts. She agreed to look for a smaller, but equally fashionable home on Madison Avenue, within baby-carriage distance of Central Park. The mansion was put on the market, and in less than a week it was sold. The family was given until the end of April to move out.4

Roosevelt simultaneously divested himself of the brownstone on West Forty-fifth Street, the only house he and his wife had ever owned. He could not bear to return there, even to close it up. Bamie was left with the sad task of “dividing everything.” Yet on 1 March, just two weeks after Alice’s death, Roosevelt signed a contract for the construction of Leeholm, at a total cost, including outbuildings, of $22,135.5 Construction began immediately, although the weather was so cold Oyster Bay was frozen in ripples. He wanted his manor finished by the summer; why was unclear, since he had no plans to move in. Bamie, ever-resourceful, indefatigable Bamie, would take care of it for him.

“I have never believed it did any good to flinch or yield for any blow,” he wrote Bill Sewall. “Nor does it lighten the pain to cease from working.”6 He did not care where he lived, for he intended to spend an absolute minimum of time eating and sleeping. Even in happier days, he had been insomniac and febrile; now his only instinct was to sleep less and labor more. The pain in his heart might be dulled by sheer fatigue, if nothing else. “Indeed I think I should go mad if I were not employed.”7

And so, on 18 February, the Assemblyman returned to Albany.

![]()

HIS ACTIVITIES, through the remainder of the session of 1884, were so prodigious that one gropes, as so often with Theodore Roosevelt, for an inhuman simile. Like a factory ship in the whaling season, he combined the principles of maximum production and perpetual motion. The naked cliffs of the Hudson Valley must have grown drearily familiar to him, for he commuted constantly in his dual capacity as Assemblyman (on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays) and chairman of the City Investigating Committee (on Fridays, Saturdays, and Mondays). Often as not he got his only sleep on the overnight train. The House was now sitting in the evenings as well as daytime, while the committee’s hearings began at ten in the morning and lasted until six.8

Thus we find him, on, say, Monday, 25 February, interrogating a New York corrections officer on illegal charges for the transport of prisoners; on Tuesday 26 rising in the Assembly to urge passage of his Municipal Indebtedness Bill; on Wednesday 27 amending a Bill for the Benefit of Colored Orphans, and reporting four bills out of his regular Cities Committee. On Thursday 28 he brings out seven more bills, whose subjects range from security to sewers; on Friday 29 he is back at the New York investigating table, demanding information on clerking procedures in the Surrogate’s Court, political patronage in the Bureau of Citations, and research fees in the Bureau of Arrears; next day, Saturday, 1 March, after an exhausting spell of testimony on drunkenness and sex in city jails, he agonizes over, and finally signs, the Leeholm contract. That night he tries to rest, but without much success (“He feels the awful loneliness more and more,” Corinne tells Elliott, “and I fear he sleeps little, for he walks a great deal in the night, and his eyes have that strained red look”).9 At 10:00 A.M. on Monday he gavels another investigative session to order; twenty-four hours later, he is in Albany, moving some banking legislation to the third reading, and making a major speech on behalf of his Liquor License Bill; on Wednesday afternoon he reports twelve new bills out of the Cities Committee, and on Thursday night a further seven; in New York next morning, he begins a final long weekend of hearings (his committee’s report is due the following Friday). While awaiting counsel’s draft of this document, he makes another major speech on municipal government, reports out of various committees a total of thirty-five new bills—the final six on Thursday evening 13 March, as he simultaneously checks every word of the Investigative Report. That night he does not sleep at all, for the text does not satisfy him—it is “a whitewashing performance”10 that ignores his committee’s most sensational findings. Roosevelt retires to the Delavan House with 1,054 pages of testimony, summons relays of stenographers, and begins to dictate a new report; when the stenographers wilt in the small hours, he sends them home and takes up the pen himself. He writes on through breakfast; at ten, when the Assembly opens, he transfers his papers there, and continues to write all morning, undisturbed by the roar of debate (although he hears enough to jump to his feet at times and comment on bills before the House). As each sheet of manuscript is finished, it is rushed to the printer. By mid-afternoon the last page is printed and bound, and the 47-page, 15,000-word document is handed in. He delivers a “masterful presentation” on its behalf, introduces nine audacious bills arising from his findings, and concludes with a request for authority to investigate other areas of city government.11

![]()

NOTWITHSTANDING ROOSEVELT’S other preoccupations, it is probable that he found time to read a front-page article in The New York Times on 25 February, for its subject-matter was of intense interest to him. The headlines read DRESSED BEEF IN THE WEST—THE BUSINESS ENTERPRISE OF THE MARQUIS DE MORES, and the copy consisted of an interview with the Frenchman, just arrived at the Hotel Brunswick. Much was made of his elegant city attire, in contrast to the broad sombrero and buckskin suit he wore out West. “The Marquis is a young man of 26, with a clear-cut and refined face and expressive gray eyes. He wears a dark brown mustache and slight sidewhiskers. He went West 18 months ago to organize the dressed beef business on the Northern Pacific Railroad. He put his first slaughterhouse on the Little Missouri. Here it was that the trouble [between himself and the three frontiersmen] occurred.…” But de Morès would not discuss “the Buffalo Bill side” of life in Dakota. He was more interested in promoting Medora as a future capital of the beef industry. The little town’s population was put at 600, and it already boasted a newspaper, the Bad Lands Cowboy. De Morès was prepared to invest a million dollars in his enterprise, and was confident of profitable returns. “In his region, he says, are the most magnificent cattle farms to be found anywhere. Grass-fed cattle keep fat all Winter.”12

![]()

ROOSEVELT’S HYPERACTIVITY did not diminish as the session wore on. If anything it increased, through two more phases of his City Investigation Committee, and two more reports totaling nearly a million words of testimony. The evidence of “blackmail and extortion” in the surrogate’s office, “gross abuses” in the sheriff’s, “no system whatever” in the Tax and Assessments Department, and “hush money” paid to policemen—interlarded with prison descriptions and brothel anecdotes which make strong reading even today—was so shocking that no fewer than seven of his nine corrective measures were passed by the Legislature.13

Since these seven bills called, among other things, for prompt cancellation of the tenure of all New York City department heads, from the bejeweled Commissioner Thompson downward, they aroused frantic opposition in the House, including one free-for-all, on 26 March, which the Evening Post called “a scene of uproar and violence to all rules of decency.”14 Hissing, howling Assemblymen ran to and fro, some hiding in the lobby in an effort to break the quorum, others besieging the Clerk’s desk with threats and denunciations. “During all this tumult,” said Isaac Hunt, “TR was the presiding genius. He was right in his element, rejoicing like an eagle in the midst of a storm.”15

The uproar was to no avail. All seven bills went on to achieve passage by overwhelming margins, despite parliamentary sabotage by Speaker Sheard.16 Roosevelt did not, however, pause to enjoy this moment of triumph over his erstwhile rival. A chance for even sweeter revenge—upon Sheard’s patron, Senator Warner Miller—lay ahead, at Utica, on 23 April.

![]()

UTICA, A SHABBY canal-town in the middle of the Mohawk Valley, was the site of the New York State Republican Convention for 1884. Four delegates-at-large, plus 128 district and alternative delegates, would be chosen for the National Convention at Chicago. When Roosevelt checked into Bagg’s Hotel on 22 April, he knew that enormous issues were at stake—issues transcending the convention’s provincial locale and rather mundane agenda. Forces had gathered all over the country to nominate James G. Blaine at Chicago, instead of President Arthur, whose political support was eroding.17 If New York, the President’s own state, voted to send a pro-Blaine delegation to Chicago, Arthur might well be deposed after serving less than one full term.

Roosevelt himself supported neither Arthur nor Blaine. The former, if only for his participation in the New York Collectorship struggle of 1877, was persona non grata to any son of Theodore Senior. The latter gave off a faint reek of legislative corruption which made the young moralist sniff with disdain. Blaine was a former Speaker of the House and Secretary of State; there was no denying his political stature and magnificent abilities. Yet for fifteen years he had been unable satisfactorily to explain certain improprieties during his Speakership, arising out of a favorable ruling in behalf of a railroad, whose bonds he had subsequently bought. As a result of this apparent self-interest, Blaine had twice been denied the Presidential nomination; but now, in 1884, party regulars seemed disposed to forgive him.18

Not so Roosevelt, who early in the New Year had endorsed the third-running candidate, Senator George F. Edmunds of Vermont.19 Edmunds was honest, industrious, unambitious, and dull, but for these very reasons he appealed to Independent Republicans—the young, idealistic reformers who identified neither with Stalwarts nor Half Breeds. Besides, he happened to suit Roosevelt’s present purpose, which was to force the state Convention to elect a pro-Edmunds delegation, and publicly humiliate Boss Miller, who was committed to Blaine.20 Utica’s Grand Opera House promised a suitably theatrical setting for his scenario.

The plot was based on a few simple political facts. There were about five hundred Republicans in town. Roosevelt, as Senator Edmunds’s most prominent supporter, would influence the votes of perhaps 70 Independents. The remaining 430-odd votes were evenlydivided between Arthur and Blaine.21 He thus stood in his favorite position—at the balance of power. Could he but persuade the 70 Independents to stand there with him, in a tight group that leaned neither one way nor the other, he would eventually be able to swing the convention in any direction he chose.

![]()

NO SOONER HAD ROOSEVELT arrived in the hotel lobby than he was besieged by excited Independents. At least forty of them followed him upstairs, and his suite immediately became known as “Edmunds headquarters.” Although the Opera House was not due to open its doors until noon the following day, negotiations began at once, in an atmosphere of whispered secrecy. Messengers sped back and forth between Roosevelt’s rooms and those of Boss Miller, representing Blaine, and those of State Chairman James D. Warren, representing President Arthur. Few serious observers believed that the Independent strength would last through the evening. “The Edmunds men … are showing their teeth,” reported the New York World, “and refuse to be coaxed by either side; but they lack organization and may find themselves outwitted.”22

Actually Roosevelt’s organization was very good. He himself was doing the outwitting. By periodically appearing in the corridors to announce, in conversational tones, that he was “no leader” of the Independents and had “no personal ambitions” at Utica, and by giving ambiguous replies to both Blaine and Arthur emissaries, he gave the impression that he was holding on to his seventy votes with difficulty. Miller and Warren thus separately assumed that Roosevelt was bargaining to release them. All the young dude wanted, obviously, was to be made a delegate-at-large. Well, if that was his price …

At six o’clock the negotiants emerged for dinner, greeted one another politely, and arranged themselves in enigmatic groups of tables. Newspapermen tried to guess, from the movement of complimentary bottles of champagne, which way the political currents were flowing; but the bottles circulated in all directions. A Sun reporter captured something of the tension in the atmosphere. “Bagg’s Hotel is filled to suffocation tonight,” he cabled. “There are no Blaine hurrahs, or Arthur enthusiasm, or Edmunds sentiment here. The old party managers are simply … groping in the dark for the coming man. There is harmony everywhere; but it is the harmony of men who are afraid of each other.”23

To Boss Miller’s bewilderment, Roosevelt proved no more tractable after dinner than he had been before. He not only rejected an offer to send one Independent delegate-at-large, i.e., himself, to Chicago, along with three Blaine men, but also refused to make the ratio two and two. News of the second rejection, which leaked out about midnight, greatly excited Chairman Warren, who offered the Independents three places on the ticket, in exchange for just one Arthur supporter; but Roosevelt also rejected that. At 2:30 A.M., the President’s men made their final, humiliating offer, an offer so weak it amounted to capitulation. All four delegates-at-large could be Independents for Edmunds, as long as there was no danger of them ultimately switching to Blaine. Roosevelt graciously accepted, knowing very well who the leader of those delegates would be.24

![]()

THERE WAS SOMETHING faintly comic, to newspaper reporters, about the sight of machine Republicans filing through the streets next morning in somber black, their tall silk hats shining in the sun. They looked for all the world like mourners at a funeral. Boss Miller walked alone, a large, portly, graying man with troubled eyes.25 Roosevelt’s rejection of his advances last night had stunned and shamed him; his mood today was not improved by an editorial in the World calling him “a pigmy” in comparision with his “giant” predecessor, Roscoe Conkling.

Arthur’s men were equally sullen and silent as they trooped into the Opera House.26 There was a round of polite applause for Chairman Warren when he mounted the stage. More applause, rather less polite, greeted Warner Miller. He took an aisle seat next to Titus Sheard on “Wood Pulp Row,” the section allotted to Herkimer County. Roosevelt, with his usual unerring sense of timing, waited until all three dignitaries were settled before making his own entrance. Then he stomped briskly down the hall, to the sound of mounting applause “that was taken up by the gallery and prolonged for some moments” after he sat down—a mere yard away from Miller, on the opposite side of the aisle. Casually draping a leg over the chair in front, he allowed his personality to penetrate every corner of the auditorium. From that moment on, there was no doubt as to who was controlling the convention. When Chairman Warren had finished calling the roll, “he simply cast his eye” over toward Roosevelt, who leaped up and proposed that an Edmunds man be nominated temporary chairman of the meeting. The motion was approved.27

![]()

BY LATE AFTERNOON, when the votes for delegates-at-large were counted, it was plain that Warner Miller had, as the Sun correspondent put it, “been pulverized finer than his own pulp.” Roosevelt’s name led the list with 472 votes. His three colleagues, all Independents, were President Andrew D. White of Cornell University with 407; State Senator John J. Gilbert with 342; and Edwin Packard, a millionaire spice merchant from Brooklyn, with 256. Boss Miller ran fifth with only 243 votes, scarcely half Roosevelt’s total, and 6 short of any kind of majority.28 His humiliation was complete. Word went around that his days as party chief were over.

Flushed with victory, Roosevelt jumped across the aisle and confronted the shaken Senator. According to one reporter, he held out his hand and said, “Time makes all things even. The first of January is avenged.”29 But the reporter was a long distance away, in the press gallery, and got this quote by proxy. Actually Roosevelt’s hand was not so much extended as balled in a fist, and his words were rather less printable: “There, damn you, we beat you for last winter!”30

“What did you want to say that for?” asked Isaac Hunt afterward. They were walking back to Bagg’s Hotel behind Miller, who had somehow torn his trousers coming out of the Opera House, and now looked infinitely pathetic.

“I wanted him to know,” Roosevelt replied.

Hunt was not impressed. “Well, I should think he would know without being told.”31

This exchange in effect ended the three-year friendship of the two young Assemblymen, which had never been the same since Hunt’s disloyalty during the Speakership contest. There is no evidence that Roosevelt took any petty offense at his colleague’s words. But he knew now that it was time to unrope himself from Hunt, O’Neil, and the other “Roosevelt Republicans,” whose horizons extended no further than New York State, and eagerly search out new altitudes, wider vistas. Chicago beckoned, and beyond it the West; could he but rise high enough, he might see his future clear.

“He grew right away from me,” Hunt confessed ruefully in old age. “I knew he was born for some great emergency, but what he would do I could not tell … I never expected to see him go right up in the heavens.”32

![]()

ROOSEVELT RETURNED TO ALBANY on 24 April to receive the congratulations of his supporters in the Assembly. “For a while,” remarked the Times, “it was a doubtful question whether the Chamber was being used for legislative purposes or as a Roosevelt reception room.”33 During the next few days he enjoyed such adulation, both public and private, as he had never enjoyed before—and would not experience again for at least a decade. The New York Times hailed him as “the victor, the wearer of all the laurels” at Utica, and the Evening Post, in the course of a long and flattering editorial, called him “the most successful young politician of our day.”34 Curiosity mounted in Chicago and Washington about the twenty-five-year-old who had almost single-handedly made Senator Edmunds a serious candidate for the Presidency. Arthur Cutler, who kept closely in touch with political trends, and took pedagogic pride in his ex-pupil, assured Bamie, “Theodore’s reputation is national and even to us who know him it is phenomenal. Whatever the future may have in store for him, no man in the country has begun his public career more brilliantly.”35

Two hundred miles away in Boston, Henry Cabot Lodge, another Edmunds supporter and delegate-at-large to Chicago, decided that Roosevelt was a “national figure of real importance,”36 and made a mental note to cultivate him.

![]()

ROOSEVELT’S POST-CONVENTION GLOW was chilled by news that Grover Cleveland was threatening to veto some of his bills for the regulation of New York City. The Assemblyman reacted with understandable shock. He had been so frequent a visitor to the Executive Office recently, and Cleveland had seemed so agreeable to all his legislation, that Roosevelt no doubt expected full cooperation through the concluding weeks of the session. (Only a few days before Utica, Harper’s Weekly had published a Nast cartoon showing the Governor obediently signing a pile of these same bills in Roosevelt’s presence.)37

Others, however, had seen signs of a showdown long ago; it was not so much a question of politics as of diametrically opposed personalities. Roosevelt was nervy, inspirational, passionate. He arrived at conclusions so rapidly that he seemed to be acting wholly on impulse, and was impatient when those with more laborious minds did not instantly agree with him.38 Cleveland, on the other hand, was slow, stolid, objective, almost maddeningly conscientious. No bill was too lengthy, or too complex, for him to scrutinize it down to the last punctuation-mark. His fathomless legal mind absorbed all data indiscriminately, sorted them into logical sequence, then issued an opinion which had about it the finality of a commandment chiseled in marble. One might as well try to sandpaper the marble smooth as to get Cleveland to change his mind.

“I never see those two together,” said Daniel S. Lamont, the Governor’s secretary, “that I’m not reminded of a great mastiff solemnly regarding a small terrier, snapping and barking at him.”39 William Hudson, of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, used a different metaphor. Cleveland was the Immovable Object, whereas Roosevelt was the Irresistible Force. Any confrontation between them was bound to generate heat—and good copy besides. So when Hudson met Roosevelt in State Street, shortly after his return from Utica, he lost no time in telling him about Cleveland’s objections to his city reform bills.40 The reaction was predictable. “He musn’t do that! I can’t have that! I won’t let him do it! I’ll go up and see him at once.” With that, Roosevelt turned and began to sprint up the hill. The reporter, scenting a story, hurried after him.

Roosevelt was already pounding on Cleveland’s desk when Hudson arrived in the Executive Office. The Governor proceeded to explain that the bills, while admirable in intent, had been too hastily written. They contained several inconsistencies which would render them ineffective as laws. Not the least of these non sequiturs was a clause in the Tenure of Office Bill specifying two different terms, of 4 years and 1 year 11 months respectively, for the same officer. There were sentences in other measures which were incomprehensible even by legal standards; the mere addition of a word or two would repair their logic; he would not sign them as presently drawn. Bristling, Roosevelt declared that “principle” was the main thing, that it was too late to worry about arcane details. “You must not veto those bills. You cannot. You shall not … I won’t have it!”

At this, Cleveland gathered up all his three hundred pounds and considerable height, visibly mushrooming in his chair. “Mr. Roosevelt, I’m going to veto those bills!” His fist crashed down with such force as to make the Assemblyman seek sanctuary in a chair, muttering something about “an outrage.” But Cleveland had already returned to his work. The interview was over.41

Thus ended the brief and unlikely political partnership of two future Presidents. They would work together again one day, and for the same cause that preoccupied them in Albany, but their relations would never be as friendly.

![]()

ALTHOUGH ROOSEVELT WAS REPORTED to be “beaming with smiles” on his return to the Capitol, he was still privately tortured with sorrow. His colleagues in the House had found him “a changed man” since the double tragedy of 14 February. “You could not mention the fact that his wife and mother had been taken away … you could see at once that it was a grief too deep.”42 There were signs that the pain inside him was increasing, rather than diminishing, due no doubt to its too cruel suppression.

Legislative work was no longer a distraction. He was offered renomination for a fourth term, but refused: he simply could not face the thought of another winter in Albany.43 With all his soul he longed now to get away from the “dull Dutch town,” away from New York with its bitter memories, away to the therapeutic emptiness of the Badlands. Even Chicago, which had so recently seemed such a thrilling prospect, now loomed like a wearisome chore. On 30 April he unburdened himself to the editor of the Utica Morning Herald, in an unusually self-revelatory letter.

I wish to write you a few words just to thank you for your kindness towards me, and to assure you that my head will not be turned by what I well know was a mainly accidental success. Although not a very old man, I have yet lived a great deal in my life, and I have known sorrow too bitter and joy too keen to allow me to become either cast down or elated for more than a very brief period over any success or defeat.

I have very little expectation of being able to keep on in politics; my success so far has only been won by absolute indifference to my future career; for I doubt if any man can realize the bitter and venomous hatred with which I am regarded by the very politicians who at Utica supported me, under dictation from masters who are influenced by political considerations that were national and not local in their scope. I realize very thoroughly the absolutely ephemeral nature of the hold I have upon the people, and a very real and positive hostility I have excited among the politicians. I will not stay in public life unless I can do so on my own terms; and my ideal, whether lived up to or not, is rather a high one.

For very many reasons I will not mind going back into private [life] for a few years. My work this winter has been very harassing, and I feel tired and restless; for the next few months I shall probably be in Dakota, and I think I shall spend the next two to three years in making shooting trips, either in the Far West or in the Northern Woods—and there will be plenty of work to do writing.44

![]()

WHEN HENRY CABOT LODGE and Theodore Roosevelt arrived in Chicago on Saturday, 31 May, they were already close friends. Earlier that month, the thirty-four-year-old Bostonian had written the twenty-five-year-old Knickerbocker, congratulating him on his election as delegate-at-large from New York, and proposing a joint visit to Washington to interview Senator Edmunds before the convention started. On the very day that Roosevelt received this letter, he had been writing a similar one to Lodge, congratulating him, in turn, on his election as delegate-at-large from Massachusetts. He accepted Lodge’s invitation “with pleasure,” and asked him to stay over at 6 West Fifty-seventh Street en route. “We are breaking up house, so you will have to excuse very barren accommodations.”45

Thus with an exchange of mutual flattery, an evening of echoing conversation in the Roosevelt mansion,46 and a pilgrimage to the city of their destiny, Lodge and Roosevelt laid the foundation of one of the great friendships in American political history.

At first sight the two men seemed an unlikely pair. Next to the wiry, bouncing, voluble Roosevelt, Lodge was tall, haughty, quiet, and dry. His beard was sharp, his coat tightly buttoned, his handshake quickly withdrawn. His eyes, forever screwed up and blinking, surveyed the world with aristocratic disdain. A heavy mustache clamped his mouth aggressively shut. On the rare occasions when the thin lips parted, they emitted a series of metallic noises which, according to Lodge’s whim, might be a quotation from Prosper Mérimée, or a joke comprehensible only to those of the bluest blood and most impeccable tailoring, or a personal insult so stinging as to paralyze all powers of repartee. Only in conditions of extreme privacy would Henry Cabot Lodge unbend an inch or so, and allow the privileged few to call him “Pinky.”47

Among his own kind, Lodge was said to be a man of considerable wit and charm;48 but the large mass of humanity, including most of the political establishment, found him repellently cold. By no amount of persuasion could he be made to see any other man’s view if it differed from his own. Those who ventured to disagree with him were crushed with sarcasm, or worse still, ignored. Although he had served only two terms in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, as opposed to Roosevelt’s three in Albany, “Lahde-dah Lodge” was already on his way to becoming one of America’s most disliked politicians.49 Yet nobody could deny that he was a man of extraordinary caliber. His promises, once made, were never broken. His treatment of both friends and enemies was unshakably fair. As for his attitude to government, it was as high-minded as a philosopher’s.

This latter characteristic, of course, attracted Roosevelt instantly. But the younger man was also drawn to Lodge’s mind, which was more erudite than his own. Lodge had not been deprived, by childhood invalidism, of a full classical education. After graduating from Harvard he had become an editor, with Henry Adams, of the North American Review, and had collaborated with that august intellectual in a book on the history of Anglo-Saxon law.50 More recently, he had published biographies of George Cabot (1877), Alexander Hamilton (1882), and Daniel Webster (1883), as well as A Short History of the American Colonies (1881). Lodge was now, in 1884, an overseer of Harvard College, chairman of the Massachusetts Republican party, and a candidate for Congress.51

No wonder Roosevelt admired this “Scholar in Politics.” Lodge, in turn, admired Roosevelt’s raw force and superior political instinct. The two had, besides, many things in common: aristocratic manners, wealth, a love of elegant clothes, membership in the Porcellian, early marriages to beautiful women (the Cabot blood shared by both Lodge and Alice Lee was another bond, albeit unspoken), massive egos, and a ruthless ambition.52 Theirs was a relationship in which occasional clashes of personality merely emphasized identical taste and breeding, as one or two dissonant notes enrich the larger harmonies of a major chord.

![]()

NO SOONER HAD ROOSEVELT checked into the Grand Pacific Hotel, New York’s headquarters, than newspapermen began to cluster around him. With his “chipper straw hat,” “natty cane,” and “new, French calf, low-cut shoes” he was “more specifically an object of curiosity than any other stranger in Chicago.”53 Lodge, too, attracted attention with his “crisp, short hair … full beard, and an appearance of half-shut eyes.”54

But it was politics, not appearances, that made reporters cluster around them. Word had spread that they might prove pivotal figures at the convention, beginning Tuesday. Under the patronage of old George William Curtis, the snowy-whiskered Civil Service Reformer and editor of Harper’s Weekly, Roosevelt and Lodge were leaders of the Independent forces. (They had spent most of the month rounding up Edmunds delegates by mail.)55 Although their power was too slight to affect the nomination of one clear favorite, they could possibly play two favorites off against each other, and then push the nomination of Senator Edmunds as a compromise. In other words, Roosevelt hoped to repeat his successful Utica performance. The numbers at Chicago were much larger, and the list of candidates longer (at least nine, as of midnight Saturday),56 but he had at least one trend in his favor: President Arthur and James G. Blaine were running neck and neck, with about three hundred delegates apiece. Edmunds lay third with ninety; all the other dark horses were far behind.

Making the most of their news value, Roosevelt and Lodge announced loudly and repeatedly that they would stay with their candidate until the end. Yet both added sotto voce, to at least one reporter, that if either Arthur or Blaine were nominated they, as loyal Republicans, would of course support him.57 It was a considerable admission, for their ideological rejection of both candidates, especially the “decidedly mottled” Blaine, was total. Editors buried the remarks beneath thousands of words of more frivolous preconvention copy.58

![]()

IN 1927 NICHOLAS MURRAY BUTLER, president of Columbia University and an old friend of Theodore Roosevelt, remembered the Republican National Convention of 1884 as “the ablest body of men that ever came together in America since the original Constitutional Convention.”59 At the time, it was considered just the opposite—“a disgrace to decency, and a blot upon the reputation of our country,” to quote Andrew D. White.60 Roosevelt himself was unimpressed by most of his fellow conventioneers. Six days of politicking with them were enough to convince him that, often as not, vox populi was “the voice of the devil, or what is still worse, the voice of a fool.”61 All the same, he certainly met most of the emerging leaders whose talents Butler so admired, and registered their faces in his photographic memory.62

Vastly outnumbering these men of the future were the “Old Guard”—veteran party members who had voted for Frémont and shed their blood for Lincoln and Grant; men who had prospered mightily under the “spoils system” for almost a quarter of a century of Republican power. They held the party and its orthodox ideology so holy that some of them cast their delegate badges in gold.63 Those from the West, and from Pennsylvania, arrived full of whiskey and love for James G. Blaine; those from the South, and from Wall Street, formed glee clubs to sing the praises of President Arthur. Both groups brought bags of “boodle” to purchase the votes of uncommitted delegates. They looked askance at the Edmunds men, who not only refused to be bought, but sanctimoniously shut up shop on Sunday morning. Independents were promptly accused of having more ice than blood in their blue Northeastern veins, and it became standard procedure, whenever anybody like Henry Cabot Lodge walked by, for members of the Old Guard to turn up their coat collars and shiver ostentatiously.64

The “schoolboy” Roosevelt, with his “inexhaustible supply of insufferable dudism and conceit,”65 aroused their particular scorn, even though they could not help being impressed by his mental powers. One old delegate remarked, after meeting him, that “all the brains intended for others of the Roosevelt family had evidently fallen into the cranium of young Theodore.”66

To see the Chicago Convention as far as possible through Roosevelt’s eyes, it is necessary to remember how desperately he had been driving himself through the last three months, how full of private grief he was, and how he longed during this final crescendo of political bedlam for the silence and solace of the Badlands. The events of the next week may best be visualized through a red blur of fatigue, which thickened as day followed night with barely a pause for sleep.

![]()

MIDNIGHT, MONDAY, 2 JUNE. Every room, stairway, and corridor in the Grand Pacific Hotel is crammed with garrulous, perspiring delegates. It takes one reporter a quarter of an hour to fight his way up from the lobby to Arthur headquarters, on the third floor. “All the corrupt element in the Republican party,” he notes en route, “seems to be concentrated here working in behalf of Blaine.”67 Brass bands thump in the streets outside, the President’s glee clubs roar discordantly, and tabletop orators shout themselves hoarse; but the most omnipresent sound is the soft rustle of “boodle.” Thomas Collier Platt of New York, Blaine’s unofficial treasurer, is rumored to be paying the highest price for votes. Arthur men are running out of money in the effort to compete with him, and impatiently await the arrival of a $50,000 parcel from New York City.68 Meanwhile they bolster their bribes with promises of federal jobs. Some wily colored delegates, trading on the white man’s traditional inability to distinguish one black face from another, sell themselves over and over to both major candidates, stocking up on free cheese and whiskey, and steadily escalating their prices. The going rate for a black Arkansas vote is already $1,000.

“Niggers,” growls one Arthur lieutenant, “come higher at this convention than any since the war.”69

![]()

10:00 A.M., TUESDAY, 3 JUNE. Warm, radiant spring weather.70 The lake “velvety-violet,” the trees along Michigan Avenue dense with new leaves. Atop the arched glass roof of Exposition Hall, a hundred flags flutter and snap. Ten thousand people mill excitedly about: spectator tickets are selling at $40 each.71

Inside the hall, an immense, luminous space, so bright with red, white, and blue bunting that at first it sends a tiny stab of pain into the eyes. An acre or more of light cane chairs, banked up row upon row like the seats of a Roman amphitheater. Parterres, galleries, even the high, wide-open windows are already packed with human flesh. Somewhere a band is playing Gilbert and Sullivan. In the distance, at the focal point of the hall, the chairman’s podium is a pyramid of flags and flowers. In front of it hangs a portrait of the assassinated Garfield, replacing the traditional martyr’s image of Lincoln.72

George William Curtis enters on Theodore Roosevelt’s arm, at the head of the New York delegation. He is gloomily pleased to note Lincoln’s absence. “Those weary eyes … are not to see the work that is to be done here,” he grunts.73 After thirty-six hours of intensive lobbying, the Edmunds men know that they have little chance of preventing the nomination of James G. Blaine. For all his shabby past, for all his two previous failures to capture the nomination, and for all his sincere protestations that the Presidency is not for him, the “Plumed Knight” has an inexplicable hold upon both party and public. The mere sight of his boozy, silver-bearded features in a train window is enough to make women weep with adoration, and men vow to God that they will never vote for any other Republican. These same features are now ubiquitous on badges and banners and transparencies all over Chicago—and all over Exposition Hall, as the delegates stream in.

The Independents have one slender hope of averting a Blaine landslide. Late yesterday the news reached them that the Republican National Committee had designated Powell Clayton, a flagrant supporter of Blaine, to be temporary chairman of the convention. Working through the night, Roosevelt and Lodge have built up enough opposition, among Arthur men as well as their own delegates, to defeat Clayton and elect, instead, John R. Lynch, an honorable black Congressman from Mississippi. Should this opposition hold through today’s balloting, the convention will at least be assured of neutral guidance from the Chair.74

At twenty minutes past noon the enormous building is at last full. The band plays “My Country ’Tis of Thee,” and the convention is rapped to order. A chaplain drones the opening prayer. The first item on the agenda is the election of a chairman, and Powell Clayton’s name is duly announced. Then, in pin-drop silence, the skinny figure of Henry Cabot Lodge stands up. His grating voice fills the hall. “I move you, Mr. Chairman, to substitute the name of the Hon. John R. Lynch, of Mississippi.”75

There is a buzz of indignation. Members of the Old Guard protest Lodge’s motion. For forty years, roars one delegate, the party has automatically endorsed the National Committee’s choice for convention chairman; to suggest somebody else is an act of rank disloyalty. Finally Roosevelt has a chance to rise in support of his friend. Leaping onto a chair and squashing down his wayward spectacles, he begins to speak—with such obvious effort that his body shakes.76

Mr. Chairman, it has been said by the distinguished gentleman from Pennsylvania that it is without precedent to reverse the action of the National Committee … there are, as I understand it, but two delegates to this convention who have seats on the National Committee; and I hold it to be derogatory to our honor, to our capacity for self-government, to say that we must accept the nomination of a presiding officer by another body …

It is now, Mr. Chairman, less than a quarter of a century since, in this city, the great Republican party organized for victory and nominated Abraham Lincoln, of Illinois, who broke the fetters of the slaves and rent them asunder forever. It is a fitting thing for us to choose to preside over this convention one of that race whose right to sit within these walls is due to the blood and the treasure so lavishly spent by the founders of the Republican party.77

This brief speech, interrupted six times by applause, is his only attempt at oratory during the convention. It is praised as “neat and effective,” “blunt and manly.” But the significance of the fact that Roosevelt, in his maiden speech before a national audience, has sought to elevate a black man will not be fully appreciated for many years.78

Lynch is elected by 424 votes to Clayton’s 384, a narrow but dramatic victory. Roosevelt, bobbing up and down nervously, accepts congratulations from all over the floor. Judge Joseph Foraker of Ohio is seen engaging him in long and friendly discourse. “I found Mr. Roosevelt to be a young man of rather peculiar qualities,” Foraker notes later. “He is a little bit young, and on that account has not quite so much discretion as he will have after a while.”79

At midnight Roosevelt is still strenuously “booming” for Edmunds. His estimates of the Senator’s strength are noticeably larger than anybody else’s.80

![]()

WEDNESDAY, 4 JUNE. A dreary, drizzly day. Routine business in Exposition Hall does not disguise the fact that more and more delegates are pledging themselves to Blaine. The Independents cannot hide their weariness and disillusionment. Only Roosevelt, says theNew York Sun, is still “bubbling with martial ardor” as he dashes to and fro on behalf of his candidate.81 All day long, through the evening session, and on into the early hours of Thursday morning, he continues his hopeless battle. He has long since realized that ninety Edmunds men cannot stop the Plumed Knight; their only hope now is to join ranks with those supporting some other reform candidate, such as John Sherman or Robert Lincoln. Meanwhile, both he and Lodge are plotting to delay the final ballot as long as possible, in the hope that Blaine’s men will eventually begin to fight each other out of sheer frustration.

![]()

THURSDAY, 5 JUNE. Solid rain and sullen tempers. The delay strategy seems to be working: there are rumors that balloting will not begin until tomorrow, maybe even Saturday. Sporadic fistfights and cane-whackings break out in the Grand Pacific Hotel.82 By the time Exposition Hall opens its doors, even Roosevelt is too tired to vault to his seat. He plods purposefully down the aisle, surrounded by an anxious crowd of Independents. Later, he is glimpsed “with his arm around some Ohio delegate’s neck,” tugging restlessly at his mustache and “looking out of the corner of his eyeglasses at the ladies in the east box.”83

During the long, tension-filled reading of the party platform, and through the hours of irascible debate that follow, Congressman William McKinley of Ohio suddenly emerges as a leading figure in the convention. With unctuous smile and soothing voice, he moves about the floor, quelling arguments before they spread. In the words of Andrew D. White, he is “calm, substantial, quick … strong … evidently a born leader of men.” As McKinley’s star brightens, Roosevelt’s begins to fade. Exhaustion is setting in. He rises to question a point of procedure, and is crushed by the retort that the point has already been made clear. As he apologizes (“I did not distinctly hear”) and sits down, some sparrows fly in from outside and squat mockingly on the gas fixture above his head.84

The nominating speeches begin at 7:30 P.M. and continue long past midnight. Twelve thousand pairs of lungs, and forty gas chandeliers, suck more oxygen out of the air than the windows can replenish. Yet Roosevelt remains wide awake throughout the evening’s interminable oratory. He writes Bamie afterward:

Some of the nominating speeches were very fine, notably that of Governor Long of Massachusetts [for Edmunds], which was the most masterly and scholarly effort I have ever listened to. Blaine was nominated by Judge West, the blind orator of Ohio. It was a most impressive scene. The speaker, a feeble old man of shrunk but gigantic frame, stood looking with his sightless eyes toward the vast throng that filled the huge hall. As he became excited his voice rang like a trumpet, and the audience became worked up to a condition of absolutely uncontrollable excitement and enthusiasm. For a quarter of an hour at a time they cheered and shouted so that the brass bands could not be heard at all, and we were nearly deafened by the noise.85

If The New York Times is to be believed, Roosevelt and Lodge begin another stop-Blaine movement immediately after adjournment, and work right through the night trying to marshal uncommitted delegates “behind some candidate new or old” whom everybody can support.86

![]()

FRIDAY, 6 JUNE. “Black Friday with the reformers in the Republican party,” as one correspondent puts it87—begins at 11:30 A.M. with the slam of Chairman Lynch’s gold-ringed gavel. There can be no more delays; the first ballot is called. Amid cheers, hisses, and boos, the secretary announces the tally. With 411 votes required for nomination, James G. Blaine has 334½; Chester A. Arthur, 278; George F. Edmunds, 93.88

On the second ballot, Blaine’s support increases while that of Edmunds declines. The third ballot brings Blaine within thirty-six votes of the nomination. Even now, Roosevelt will not give up. He starts rushing frantically from delegation to delegation, while Judge Foraker moves to adjourn, so that a final line of defense against Blaine can be organized. The motion is shouted down, but Roosevelt jumps into his chair, yelling for a roll call until he is red in the face. By now the entire hall is reverberating with whistles and catcalls; he continues to shout and gesticulate; when a delegate from New Jersey tells him to “sit down and stop your noise,” his temper cracks. “Shut up your own head, you damned scoundrel you!”89 The Chair rejects his point of order on a technicality. However Roosevelt does succeed, says the Chicago Tribune, “in rousing the admiring remarks of the fair sex, who enthused over his 28 [sic] years and glasses.”90

Once again William McKinley pours oil on troubled waters. “Let us have no technical objections. I am as good a friend of James G. Blaine as he has in this convention, and I insist that every man here shall have fair play.” The motion to adjourn is voted on, and defeated. Roosevelt sits “pale, jerky, and nervous” as the fourth ballot proceeds. “I was at the birth of the Republican party,” murmurs old George William Curtis, “and I fear I am to witness its death.”91

The sun streams in through high windows, flooding the hall with yellow light. A secretary begins to announce the tally. One Arthur delegate retires to the wings, brushes tears from his eyes, and changes his purple badge for a white one. It is all over.92 In a hurricane of hats, umbrellas, and handkerchiefs, and what is generally calculated to be the loudest roar in the history of American politics, McKinley pushes smilingly through the crowd. He bends over Roosevelt’s chair, asks him to second a motion making the nomination unanimous. Roosevelt shakes his head. McKinley turns to Curtis. The old man shakes his head too.93

![]()

OUTSIDE, AS THE DELEGATES disperse in the warm afternoon, Roosevelt snaps at a World reporter, “I am going cattle-ranching in Dakota for the remainder of the summer and a part of the fall. What I shall do after that I cannot tell you.” Asked if he will support the party’s choice for President, he replies with angrily flashing spectacles, “That question I decline to answer. It is a subject that I do not care to talk about.”94

At midnight, he is still too wrought up to sleep. He tells an Evening Post editor that, rather than vote for Blaine, he would give “hearty support” to any decent Democrat. More than anything, this rash remark reveals that Roosevelt is politically and physically at the end of his tether.95 The editor does not print it—yet.

![]()

SATURDAY, 7 JUNE. Henry Cabot Lodge heads east to muse on the future; Theodore Roosevelt heads west to forget about the past. He craves nothing so much as the shade of his front porch, the lowing of his own cattle, the soothing scratch of his pen across paper. Yet even at St. Paul, the roar of Chicago pursues him. A reporter from the Pioneer Press demands to know if he will accept Blaine’s nomination or “bolt.” Some sixth sense warns Roosevelt that “bolt” is the most fatal word in American politics. “I shall bolt the Convention by no means,” he says at last. “I have no personal objections to Blaine.”96

With that, Roosevelt changes trains and rumbles off to Little Missouri. A boyhood ambition is rising within him. He will take a rifle, load up a horse, and ride off into the prairie, absolutely alone, for days and days—“far off from all mankind.”97

“I am going cattle ranching … what I shall do after that I cannot tell you.”

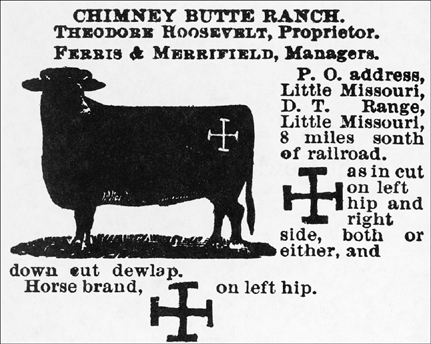

The first public advertisement of the Maltese Cross brand, 1884. (Illustration 10.2)