From his window Olaf gazed,

And, amazed,

“Who are these strange people?” said he.

![]()

THE BUILDING LOOMED PALE against a black backdrop of buttes as Roosevelt approached. Somebody had given it a coat of white paint, in an ineffective attempt to make it look respectable, and hung out a sign reading PYRAMID PARK HOTEL. Encouraged, Roosevelt hammered on the door until the bolts shot back, to the sound of muttered curses from within.1 He was confronted by the manager, a whiskery, apoplectic-looking old man. History does not record what the latter said on discovering that his boozy slumbers had been interrupted by an Eastern dude, but it was probably scatological. “The Captain,” as he was locally known, had been notorious in steamboat days for having the foulest mouth along the entire Missouri River.2

Roosevelt had only to drop the name of Commander Gorringe to reduce his host to respectful silence. He was escorted upstairs to the “bull-pen,” a long, unpartitioned, unceilinged room furnished with fourteen canvas cots, thirteen of which already had bodies in them. In exchange for two bits, Roosevelt won title to the remaining bed, along with the traditional Western “right of inheritance to such livestock as might have been left by previous occupants.”3 The cot’s quilts were rough, and its uncased feather pillow shone unpleasantly in the lamplight;4 but at two thirty on a cool Dakota morning, to an exhausted youth with five days of train travel vibrating in his bones, it must have seemed a welcome haven.

“I shall become the richest financier in the world!”

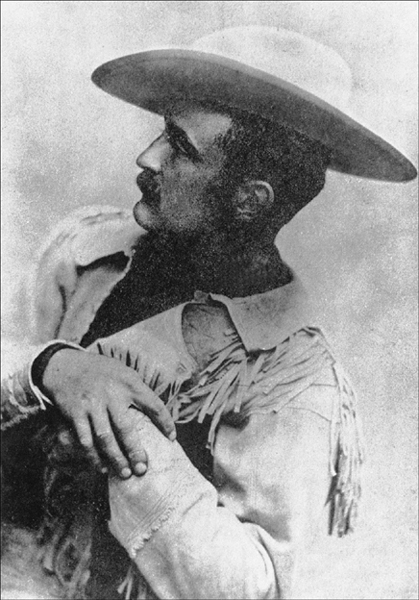

Antoine-Amédée-Marie-Vincent-Amat Manca de Vallombrosa, Marquis de Morès. (Illustration 8.1)

![]()

ROOSEVELT AWOKE EARLY next day. He did not need an alarm clock: breakfast in the Pyramid Park was routinely announced by a yell downstairs, followed by a stampede of hungry guests. There were two tin basins in the lobby, but the seamless sack towel was so filthy as to discourage ablutions. Besides, an aroma of cooking wafting out of the adjoining dining room was too distracting. For all its rough accommodations, the hotel was a famously good place to eat.5

Peering out of the dining-room window into the brilliant prairie light, Roosevelt could take stock of Little Missouri, or “Little Misery,” as residents pronounced it. Various citizens “of more or less doubtful aspect” were walking about. Next to the hotel was a ramshackle saloon entitled “Big-Mouthed Bob’s Bug-Juice Dispensary.” It advertised a house specialty, “Forty-Mile Red Eye,” guaranteed to scour the alkali dust out of any parched hunter’s throat. On the opposite side of the railroad stood a store and three or four shacks, dwarfed by the massive clay outcrop of Graveyard Butte. (A few high crosses, glinting in the sun, explained the butte’s name.) Three hundred yards downrail, on the flat bank of the river, were a pair of shabby bungalows, facing each other across the tracks; uprail near the point where Roosevelt’s train had disappeared into the bluffs, a section-house sat in the shade of a giant water tank. These few scattered buildings completed what was Little Missouri on 8 September 1883—with the exception of Gorringe’s cantonment, a group of gray log huts in a cottonwood grove, about a quarter of a mile downriver.6 Unimpressive in any context, the tiny settlement was reduced to total insignificance by the buttes hemming it in on both sides of the river, and by Dakota’s stupendous arch of sky.

For all its sleepy aspect, Little Missouri was unofficially rated by the Northern Pacific as “the toughest town on the line,”7 a place where questions of honor—or, more frequently, dishonor—were settled with six-shooters. The nearest sheriff was 150 miles to the east; the nearest U.S. marshal, over 200 miles to the south. The presence of a military detachment, assigned to guard railroad construction gangs from attacks by predatory Sioux, had until recently established some semblance of law and order in the community, but now the soldiers were gone. Only the day before Roosevelt’s arrival, a “Golden Spike Special” had passed through town, carrying dignitaries west to Montana for ceremonies marking completion of the Northern Pacific Railroad corridor.8 Ex-President Grant had been on board, and the glimpse of his profile speeding by was symbolic to Little Missouri’s fifty or sixty residents. Uncle Sam had withdrawn his protection from yet another frontier outpost; now the settlement lay open to the conflicting interests of white man and Indian, greed and conservation, law and anarchy, money and guns. A few months would determine whether Little Missouri would survive as a hunting resort, or whether, like so many obsolete railroad towns, it would become a few crumbling sticks in the wilderness.

![]()

ROOSEVELT, THAT SUNNY Saturday morning, could not have cared less about Little Missouri’s economic future. He had come West to kill buffalo; he was impatient to get out of town and into the Badlands, whose violet ravines beckoned excitingly in all directions. But first a guide must be found. The saloon was not yet open, and the Captain, grouchy from lack of sleep, would not say where else Roosevelt might recruit help. His son, a fat youth with whiskey-red cheeks, apparently inherited, was more helpful. He suggested that Joe Ferris, down at the cantonment, might be willing.9

About this time, perhaps, Roosevelt began to realize that hiring a professional guide would not necessarily guarantee him a buffalo. Commander Gorringe, anxious for clients, had doubtless intimated that buffalo were still plentiful in the Badlands, when Roosevelt first met him in May. Actually there had been several thousand animals left to shoot then, but the situation soon changed dramatically for the worse. In mid-June a band of excited Sioux, encouraged by the U.S. Government, had slaughtered five thousand buffalo on the plains just east of the Badlands. Throughout the summer, passengers on the Northern Pacific had blazed away at whatever beasts wandered near the tracks, leaving their carcasses to the successive depredations of skin hunters, coyotes, buzzards, and “bone merchants.” Less than a week before Roosevelt’s arrival in the Badlands, the Sioux had returned to kill off a herd of ten thousand survivors. Again, the slaughter was carried out with full federal approval; Washington knew that plains bare of buffalo would soon be bare of Indians too.10

Joe Ferris’s first reaction to Roosevelt’s proposal was negative. He was a short, husky young Canadian, built like “the power end of a pile driver.” Although his mustache was sad, his eyes were friendly—or was the gloom of the cantonment post store delusive?11In his twenty-five-odd years, Ferris had laid railroads, jacked lumber, managed stables, and guided a succession of buffalo hunters through the Badlands, before accepting the job of barn superintendent for Commander Gorringe. For all his out-of-doors background, he was of sedentary disposition; the prospect of another expedition in pursuit of a vanishing species did not appeal to him. Neither, for that matter, did this new dude, with his owlish spectacles and frenzied grin.12 But the dude proved remarkably persuasive. There was about him the intoxicating smell of money—and Joe Ferris, whose private ambition was to become the first banker in Little Missouri, found himself agreeing to be Roosevelt’s guide for the next two weeks.

![]()

THE TWO MEN SPENT most of the afternoon loading a buckboard with provisions and hunting equipment. By the time they rolled out of town to the ford just north of the railroad trestle, the sun was already low over Graveyard Butte. Before crossing over to the east bank of the river, they stopped at one of the downrail bungalows to borrow an extra buffalo-gun. Roosevelt had discovered that the hammer of his big Sharps .45-caliber rifle was broken. He had brought a spare Winchester, but Ferris thought the latter was too light to rely on.13

The owner of the bungalow stood tall, cold, and quiet as Ferris asked the favor. He was a grizzled, villainous-looking man with pale eyes, a black goatee, and mandarin mustaches dangling below his chin. A pair of revolvers rode easily on his narrow hips.14Surprisingly, he agreed to lend the gun without a deposit, and also supplied a new Sharps hammer.

No doubt Roosevelt had plenty of questions to ask about this sinister person as the buckboard splashed across the shallow river. He would have questions, too, about what looked like a rival settlement to Little Missouri, in the process of construction on the sagebrush flats opposite; questions about a giant brick chimney in the midst of the unfinished buildings; questions about a magnificent new ranch house perched on a bluff about half a mile to the southwest, and dominating the entire valley; questions about the crosses on Graveyard Butte (starkly etched now against the setting sun); questions arising out of these questions, and many more besides. It would have taken a harder man than Joe Ferris to withstand the drilling force of Roosevelt’s curiosity. The odds are that by the time the buckboard had swung south across the sagebrush flats, Ferris had begun to answer in detail, and that the full story, linking all Roosevelt’s objects of inquiry, emerged as they rumbled on upstream in the deepening twilight.

![]()

THE MAN IN THE BUNGALOW was Eldridge G. Paddock, éminence grise of the Badlands. Long before the Northern Pacific first reached the river in 1880, Paddock had held undisputed sway over the valley’s roving population of hunters, trappers, and traders. He had been one of the first to settle near the Little Missouri depot, and quickly became known as “the sneakiest man in town, always figuring on somebody else doing the dirty work for him, and him reap the benefits.” Although Paddock was a silent, solitary man, rarely seen to engage in open violence, people who annoyed him had a way of being found with their heads caved in, or with bullets in their backs; he was said to be personally responsible for at least three of the crosses on Graveyard Butte. Yet he was capable of surprising generosity (as Roosevelt had just discovered) and was apparently straight with his friends. All in all, he was an enigmatic character against whom nothing had ever been proven.15

Until last winter, Paddock had been content, publicly at least, to flourish as a gambler, guide, and speculator in hunting rights up and down the river. Then, early in the spring, there stepped off the train at Little Missouri a man of unlimited wealth and unlimited gullibility. “I am weary of civilization,” declared the stranger.16 Paddock pounced on him with the sureness of Iago accosting Othello.

The newcomer was a very dark, very handsome young Frenchman, with eagle eyes, waxed mustaches, and military bearing. His name bespoke a lineage both noble and royal, dating back to thirteenth-century Spain: Antoine-Amédée-Marie-Vincent-Amat Manca de Vallombrosa, Marquis de Morès. Local parlance speedily reduced it to “de Moree,” and then, as summer wore on, to “that son of a bitch of a Marquis.”17

De Morès had come to the Badlands to invest in the local beef industry. Although as yet this industry consisted only of six or seven scattered ranches, he seemed sure that he would prosper. “It takes me only a few seconds to understand a situation that other men have to puzzle over for hours,” he boasted.18 Certainly the prospects seemed good, even to the slow-witted. Here, and for thousands of square miles around, were juicy pastures, sheltered bottoms, and open stretches of range whose ability to support countless thousands of bovine animals had been demonstrated over the centuries. Now that the buffalo and red men were on their way out, cattle and white men could move in. The Marquis proceeded to unfold a series of ambitions so grandiose as to stun his buckskinned audience. He would buy up as many steers as the Badlands could produce, plus as many more as the Northern Pacific could bring in from points farther west. He would build a gigantic slaughterhouse in the valley, process his beeves on the spot, and ship the meat East in refrigerated railroad cars. This would save the trouble, expense, and quality loss of transporting cattle on the hoof, resulting in lower prices for the Eastern consumer, higher profits for the Western producer, and untold riches for himself. “I shall become the richest financier in the world!”19 He was so sure of the scheme’s success that he would spend millions—tens of millions, if necessary. With the resultant billions, he would buy control of the French Army, and mount a coup d’état for what he believed (apparently with some justification) was his birthright—the crown of France.20

The shabby citizens of Little Missouri listened to de Morès with understandable skepticism. All except E. G. Paddock decided they would have nothing to do with the “crazy Frenchman.” So, on 1 April 1883, the Marquis crossed over the river, erected a tent on the sagebrush flats, cracked a bottle of champagne over it, and announced that he was founding his own rival town. It would be named Medora, after his wife.21

(Roosevelt probably knew, at least indirectly, the lady in question; for that matter, he may even have heard of de Morès before. Medora von Hoffman was, like himself, a wealthy young New York socialite; her father, Louis von Hoffman, was one of the richest bankers on Wall Street. De Morès had wooed the redheaded heiress in Paris, married her in Cannes, and come to live with her in New York in the summer of 1882. For a while, the Marquis had worked at the family bank, but he was of restless disposition, and decided to go West in search of wider horizons. The person who prompted him to visit Little Missouri was none other than that ubiquitous entrepreneur, Commander Gorringe.22)

Local cynics noted with delight that the date de Morès chose to smash his champagne bottle was April Fools’ Day. But the foam had scarcely soaked into the sagebrush before the sounds of construction disturbed the peace of the valley. Gangs of workers began to arrive from St. Paul, and the new town arose with astonishing speed. Higher and faster than anything else soared the Marquis’s slaughterhouse chimney, until the citizens of Little Missouri, glancing across the river, could not help but see it. Huge and phallic against the eastern buttes, it stood as a symbol of future glory and the unlimited power of money.23 When Roosevelt and Ferris rolled past on their buckboard, on 8 September 1883, the slaughterhouse was only two weeks from completion.24

Another, more ominous symbol was the Marquis’s hilltop ranch house, which he grandiloquently called “Château de Morès.” It, too, was nearing completion when Roosevelt drove by. Gray and forbidding, the Château commanded a panorama of both Little Missouri and Medora which could only be described as lordly. This was plainly the home of an aristocrat who regarded himself as far above the vassals in the valley. Roosevelt, if he was not reminded of his own pretensions at Leeholm, may have compared it to the “robber knight” castles he and Alice had seen while cruising down the Rhine, two summers before. “The Age of Chivalry was lovely for the knights,” he had mused then, “but it must have at times been inexpressively gloomy for the gentlemen who had to occasionally act in the capacity of daily bread for their betters.”25

Some inhabitants of the Little Missouri Valley, at any rate, did not intend to become daily bread for the Marquis. Among them were three frontiersmen, Frank O’Donald, Riley Luffsey, and “Dutch” Wannegan. O’Donald had been offered work by de Morès sometime in the spring, but he had refused, saying that he preferred to live on the proceeds of hunting and trapping. Besides, he was an old enemy of E. G. Paddock—and Paddock was already the Marquis’s right-hand man. De Morès shrugged and forgot about him. Then one day O’Donald rode home to the hunting-shack he shared with Luffsey and Wannegan, ten miles downriver, and discovered a fence across his path. Inquiries revealed that it had been erected by the Marquis, who was buying up large tracts of public land with Valentine script. O’Donald angrily hacked the fence down. De Morès coolly put it up again. Every time O’Donald and his friends rode up and down the valley, they destroyed the fence, only to find it blocking their path on the way back. Tempers began to rise; threats were shouted across the river. Then, in mid-June, came the final straw. O’Donald heard a rumor—allegedly bruited about by E. G. Paddock—that the Marquis was about to “jump claim” to his hunting-shack. “Whoever jumps us,” O’Donald announced publicly, “jumps from there right into his grave.”26

On Thursday, 21 June, the three frontiersmen arrived in Little Missouri for a long weekend of drinking and shooting. One witness described it as “a perfect reign of terror.” The air was thick with promiscuous bullets, and O’Donald, primed with Forty-Mile Red Eye, repeated his threats to shoot de Morès “like a dog on sight.” After two days of this, Paddock felt constrained to ride over to Medora and warn the Marquis that his life was in danger. De Morès promptly took the next train east to Mandan, 150 miles away, and reported the situation to a justice of the peace. “What shall I do?” he asked. “Why, shoot,” replied the J.P.27

The Marquis, who was an expert marksman and no coward (he had already killed two Frenchmen in affaires d’honneur),28 returned nonchalantly to the valley on Monday, 25 June. Waiting for him at the Little Missouri depot were his three rather hung-over enemies. Possibly de Morès stared them down; at all events they allowed him to pass. But later that afternoon, as he stood talking to Paddock outside the latter’s bungalow, a bullet cracked past him, missing by less than a yard.29

Even then, de Morès somehow retained his European reverence for the law. He telegraphed to Mandan for a sheriff, and retired to Medora to await the next train. It was not due to arrive until Tuesday afternoon. To make sure that his antagonists did not leave town before then, the Marquis posted aides on all the trails leading out of Little Missouri. On Tuesday morning he himself staked out a bluff west of town, overlooking the most likely escape route the frontiersmen would take if they sought to avoid the sheriff. Tension gathered as the hour of the train’s arrival approached. Presently the puffing of a locomotive was heard in the east. O’Donald, Luffsey, and Wannegan mounted their horses and rode over to the depot.

As expected, the sheriff was on board the train. Stepping down into the sagebrush, he found himself staring into the barrels of three rifles. When he told the trio he had a warrant for their arrest, O’Donald replied, in classic Western fashion, “I’ve done nothing to be arrested for, and I won’t be taken.” With that, they turned and rode out of town. While the sheriff watched indecisively, the frontiersmen headed straight into the ambush de Morès had prepared for them. There were two, apparently simultaneous explosions of gunfire; the three horses collapsed and died; the firing continued; then, with a scream of “Wannegan, oh Wannegan!” Riley Luffsey fell dead, a bullet through his neck. Another bullet smashed into O’Donald’s thigh, and Wannegan’s clothes were shot to ribbons. They surrendered instantly.

When the dust and smoke cleared, de Morès, Paddock, and two other aides were seen emerging from various hiding-points in the sage. The sheriff arrested all except Paddock, who, having taken care not to be seen participating in the ambush, insisted that the frontiersmen had started the shooting anyway.

At a noticeably sympathetic hearing in Mandan at the end of July, murder charges against the Marquis and his men were dismissed for lack of evidence. There was talk in Little Missouri of lynching de Morès if he ever dared to return to Medora. With characteristic courage he did so immediately; not a hand was laid on him. Construction at Medora went on, and more fences went up in the valley. By the time Roosevelt arrived in the Badlands, a month later, uneasy calm had been restored. But a new cross stood out white and clean on Graveyard Butte, as if in silent protest that Riley Luffsey’s death had not been avenged.

This, then, was the story, an authentic tale of the Wild West, that Roosevelt soon came to know by heart, for it was told over and over again in the Badlands, that fall of 1883. Events which the New Yorker could not foresee would one day involve him with all its major characters.

![]()

NO SOONER HAD ROOSEVELT and Ferris crested the butte south of Medora and rolled down the far side than a wall of rock screened off the puny outpost of civilization behind them.30 All memory of the Marquis’s grand chimney was obliterated by the craggy immensity opening out ahead. As far as Roosevelt’s eye could see, the landscape was a wild montage of cliffs and ravines, tree-filled bottoms and grassy divides. Here and there a particularly lofty butte caught the last rays of the sun, and glowed with phosphorescent brilliance before fading to ashen gray.31 Nowhere was there any sign of human life, save for an almost invisible wagon trail zigzagging from side to side of the crazily meandering river. Sometimes the trail disappeared completely in meadows of lush, three-foot grass (here, presumably, buffalo once fed); sometimes it ran in straight furrows across beds of dried mud that gave off choking clouds of alkali dust under the horses’ hooves.

They had been traveling south steadily for almost an hour before Roosevelt saw the first settler’s log house, near the mouth of Davis Creek. Joe Ferris told him it was named Custer Trail Ranch, after the doomed colonel who had camped there in 1876. Another, even earlier expedition had taken this trail in 1864, led by the old Sioux-baiter, General Alfred Sully. It was he who coined the classic description of the Badlands: “hell with the fires out.”32 Seen by Roosevelt in the gloom of early evening, it must indeed have seemed like a landscape of death. There were pillars of corpse-blue clay, carved by wind and water into threatening shapes; spectral groves where mist curled around the roots of naked trees; logs of what looked like red, rotting cedar, but which to the touch felt petrified, cold, and hard as marble; drifts of sterile sand, littered with buffalo skulls; bogs which could swallow up the unwary traveler—and his wagon; caves full of Stygian shadow; and, weirdest of all, exposed veins of lignite glowing with the heat of underground fires, lit thousands of years ago by stray bolts of lightning. The smoke seeping out of these veins hung wraithlike in the air, adding a final touch of ghostliness to the scene. Roosevelt could understand why the superstitious Sioux called such territoryMako Shika, “land bad.”33

Early French trappers had expanded the term to mauvaises terres à traverser, “bad lands to travel over.” That usage, too, Roosevelt could understand; he and Ferris had to ford the river twice more, and hack through a thicket of cottonwood trees, before arriving at their night stop, a small log hut in a mile-wide valley. This, announced Joe, was the Maltese Cross Ranch, home of his brother Sylvane, and another Canadian, Bill Merrifield.

![]()

THE TWO RANCHERS greeted Roosevelt coldly. They did not care for Eastern dudes, particularly the four-eyed variety. (Spectacles, he found out, “were regarded in the Bad Lands as a sign of defective moral character.”)34 Quiet, ill-lettered, humorless, and whipcord-tough, the pair were just beginning to prosper after two years of hunting and ranching on the Dakota frontier. Their herd of 150 head had been supplied by two Minnesota investors on the shares basis customary in those days of “free grass” and absentee owners. In exchange for their management on the range, Sylvane and Merrifield were paid a portion of the profits arising from beef sales. Roosevelt was probably curious about operations at Maltese Cross (the name derived from the shape of the ranch brand), since he himself had some time ago invested five thousand dollars in a Cheyenne, Wyoming, beef company; but his hosts were not the kind to discuss business with a stranger.35

The atmosphere in the one-room cabin continued awkward through supper. Even a game of old sledge, played by lamplight after the table had been wiped over, failed to break the ice. Suddenly some frightful squawks through the log walls distracted them. A bobcat had gotten into the chicken-house, which was jabbed against the side of the cabin. Rushing outside, the four cardplayers joined in a futile chase, and when they returned they were laughing and talking freely at last.36

Despite this new friendliness, Sylvane and Merrifield were reluctant to lend Roosevelt a saddle horse for his buffalo hunt. He and Joe had decided to base their operations around Little Cannonball Creek, forty-five miles to the south, in the hope that some stray buffalo might still be found there. Roosevelt did not relish the prospect of having to spend the whole next day jouncing around on the buckboard. He pleaded for a horse, but in vain: the ranchers “didn’t know but what he’d ride away with it.” Only when he took out his wallet, and offered to buy the horse for cash, did their resistance magically melt.37

Noblesse oblige prevented Roosevelt from taking one of the three bunks available in the cabin that night. He simply rolled up in his blankets on the dirt floor, under the dirt roof.38 Had he known what privations he was to suffer during the next two weeks, even this would have seemed like luxury.

![]()

AT DAWN THE NEXT DAY Roosevelt mounted his new buckskin mare, Nell, and turned south up the valley, with Joe Ferris’s wagon rumbling behind. In the clear light of early morning he could see that the Badlands were neither hellish nor threatening, but simply and memorably beautiful. The little ranch house, alone in its bottomland, commanded a magnificent view of westward rolling buttes. Their sandstone caps broke level: flat bits of flotsam on a tossing sea of clay.39 The nearer buttes, facing the river, were slashed with layers of blue, yellow, and white. In the middle distance these tints blended into lavender, then the hills rippled paler and more transparent until they dissolved along the horizon, like overlapping lines of watercolor. Random splashes of bright red showed where burning coal seams had baked adjoining layers of clay into porcelain-smooth “scoria.” Thick black ribs of lignite stuck out of the riverside cliffs, as if awaiting the kiss of more lightning. Their proximity to the Little Missouri told the whole geological story of the Badlands. Here two of the four medieval elements—fire and water—had met in titanic conflict. So chaotic was the disorder, wherever Roosevelt looked, that the earth’s crust appeared to have cracked under the pressure of volcanic heat. Millions of years of rain had carved the cracks into creeks, the creeks into streams, the streams into branchlets, the branchlets into veinlets. Each watercourse multiplied by fours and eights and sixteens, until it seemed impossible for the pattern to grow more crazy. Even so, as he rode south, he could see strange dribbles of mud in dry places, and puffs of smoke curling out of split rocks, which signified that water and fire were still dividing the earth between them.

Apart from dense groves of willow and cottonwood by the river, and clumps of dark juniper on the northern-facing slopes, the Badlands were largely bare of trees. A blanket of grass, worn through in places but much of it rich and green, softened the harsh topography. Wild flowers and sagebrush spiced the clean dry breeze—blowing ever hotter as the sun climbed high. Surely Roosevelt’s asthmatic lungs rejoiced in this air, as did his soul in the sheer size and emptiness of the landscape. No greater contrast could be imagined to the “cosy little sitting room” on West Forty-fifth Street. Here was masculine country; here the West was truly wild; “here,” he confessed many years later, “the romance of my life began.”40

![]()

FOR MILE AFTER MILE, hour after hour, the hunters straggled south over increasingly rugged country. No wagon trail now: six times that morning they had to ford the river as it meandered across their path. About noon they mounted a high plateau, whose views extended west to Montana. Dropping down again into the Little Missouri Valley, they forded the river at least seventeen more times. There were bogs and quicksands to negotiate, and banks so steep the buckboard was in danger of toppling over. The sun was already glowing red in their faces when they sighted their destination, a lonely shack in a meadow at the mouth of Little Cannonball Creek. It was dusk by the time they got there. Lamplight shone invitingly out of the shack’s single window.41

![]()

LINCOLN LANG, a sixteen-year-old Scots lad sporting his first American suntan, was just sitting down to supper with his father, Gregor, when he heard the sound of hooves and wheels outside. Through the window he recognized the burly shape of Joe Ferris, but the skinny figure on horseback was obviously a stranger.42 Gregor Lang went out to greet his visitors. The boy followed hesitantly, and received one of those photographic impressions which register permanently on the adolescent mind.

Aided by the beam of light showing through the cabin door, I could make out that he was a young man, who wore large conspicuous-looking glasses, through which I was being regarded with interest by a pair of twinkling eyes. Amply supporting them was the expansive grin overspreading his prominent, forceful lower face, plainly revealing a set of larger white teeth. Smiling teeth, yet withal conveying a strong suggestion of hang-and-rattle. The kind of teeth that are made to hold anything they once close upon …

“This is my son, Mr. Roosevelt,” [Father] said. Then somehow or other I found both my hands in the solid double grip of our guest. Heard him saying clearly but forcefully, in a manner conveying the instant impression that he meant what he said …

“Dee-lighted to meet you, Lincoln!”

… Young and all, as I was, the consciousness was instantly borne in upon me of meeting a man different from any I had ever met before. I fell for him strong.43

The Langs had been living in the shack for only three weeks. They had spent the summer in Little Missouri, where their presence was somewhat less than welcome, for Gregor Lang had been sent there in an investigative capacity. His employer, a British financier, had been asked to buy shares in Commander Gorringe’s Little Missouri Land and Stock Company. Before doing so, the financier felt that some close Scots scrutiny was needed.

Lang had viewed with Presbyterian disapproval the hard drinking and dubious bookkeeping of Gorringe’s employees, and his reports back to London were not encouraging. Yet he could see that there was money to be made in the Badlands, and great opportunities to exploit. America had always inspired and challenged this bewhiskered scholarly man. He had named his own son after the Great Emancipator, and here, in “God’s own country,” freedom beckoned them both. With the blessings—and backing—of the British financier, he had come to Little Cannonball Creek to open a new ranch. As yet it was only a log cabin with sod on the floor and rats in the roof, but a herd was ready to be brought in from Minnesota, Mrs. Lang was on her way across the Atlantic, and his ambitions were large.44

Roosevelt, finding Lang to be the first pioneer of intellectual quality that he had met, immediately set about pumping him dry of dreams and practical knowledge. Lang responded readily: his summer among the monosyllabic citizens of Little Missouri had left him starved for good discourse. Long after supper that night, long after Joe Ferris had wearily gone to bed, the two men talked on by the light of the lantern, while wolves howled in the distant buttes, and young Lincoln struggled to keep awake. Never had he heard his father so loquacious, so drawn out by insistent questioning. As for their guest’s conversation, it was the most fascinating he had ever heard.45 Yet the boy, willy-nilly, nodded off at last. So, it is safe to assume, did Gregor Lang, or Roosevelt would have talked all night. Some enormous idea seemed to be taking possession of him, an aspiration so heady it would not let him sleep.

![]()

HE SLEPT ENOUGH, at any rate, to be up at dawn. The sound of rain drumming fiercely on the cabin’s roof did not deter him from beginning his buffalo hunt immediately. Joe Ferris protested they should wait until the weather cleared, and the Langs warned that he would find the clay slopes round about too greasy to climb. But “he had come after buffalo, and buffalo he was going to get, in spite of hell or high water.”46 At six o’clock Roosevelt and Ferris mounted their horses and rode east into a wilderness of naked, streaming hills.

All day the rain continued. The clay slopes, slimy to begin with, dissolved into sticky gumbo, and finally into quagmires that sucked at the horses’ hooves, and squirted jets of black mud over the riders. Tracking was impossible: a buffalo might trot through this landscape and leave deep spoors, but within minutes they would disappear, like holes in dough. Visibility was wretched: no matter how often Roosevelt wiped his swimming spectacles, his vision would blur again, reducing the Badlands to a wash of dark shapes, any one of which might or might not be game. Often as not, a promising silhouette turned out to be a mere mound of clay, topped with a “head” of sandstone.

Eventually they encountered a few deer. Roosevelt fired at a buck from too far away, and missed. Joe Ferris followed up with a shot in a thousand, and brought the bounding animal down. “By Godfrey!” exclaimed his frustrated client. “I’d give anything in the world if I could shoot like that!”47

Not until nightfall did they return to the ranch. The Langs, who had been expecting them back for breakfast, looked on in wonder as two clay men dismounted from two clay horses and squelched toward the cabin. Incredibly, Roosevelt was grinning.

![]()

HE CONTINUED TO GRIN through four more days of ceaseless rain. Joe Ferris protested every morning, and was on the point of caving in every evening, but Roosevelt seemed incapable of fatigue or despair. “Returning at night, after another day fruitless, all save misery, the grin was still there, being apparently built in and ineradicable. Disfigured with clinging gumbo he might be, and generally was; but always the twinkling eyes and big white teeth shone through.”48

Not until Lincoln was old and living in another century did he find an adjective that adequately described Roosevelt’s energy. The man was “radio-active.” Physically he was “none too robust,” yet “everything about him was force.”49 When supper was over, and Ferris rolled groaning into bed, the New Yorker would resume his conversation with Gregor Lang, and talk until the small hours of the morning. Lincoln listened for as long as he could, awed by the verbosity of “our forceful guest.” Among the subjects covered were aspects of literature; racial injustice; political reform (Lang taking the Democratic, and Roosevelt, the Republican side); the divine right of kings; Abraham Lincoln; the geology of the Badlands; human propagation (“I want to congratulate you, Mr. Lang,” Roosevelt said warmly, on learning that the Scotsman was one of fifteen brothers and sisters); hunting; conservation and development of natural resources; social structure and moral order.50 From the latter discussions young Lincoln deduced the Rooseveltian “view of life” as being

the upbuilding of a colossal pyramid whose apex was the sky. The eternal stability of this pyramid would be insured only through honest, intelligent, interworking and cooperation, to the common end of all the elements comprised in its structure. Individual elements might strive to build intensively and even high; but never well. Never well, because lacking an adequate base—the united stabilizing support of the other elements—they might never attain to the zenith.51

A pyramid built in the air, perhaps, but inspirational to a boy whose first fifteen years had been spent in a society with downward dynamics. “It was listening to these talks after supper, in the old shack on the Cannonball, that I first came to understand that the Lord made the earth for all of us, and not for a chosen few.”52

![]()

AS THE EVENINGS WORE ON, Roosevelt’s talk turned more and more to a subject which was clearly preoccupying him—ranching. “Mr. Lang,” he said one night, “I am thinking seriously of going into the cattle business. Would you advise me to go into it?”

His host reacted with Caledonian caution. “I don’t like to advise you in a matter of that kind. I myself am prepared to follow it out to the end. I have every faith in it … As a business proposition, it is the best there is.”53

Roosevelt had time to ponder this remark during long wet hours on the trail. But on the sixth day of the hunt, the sun finally broke through, and his thoughts returned with fierce concentration to the pursuit of buffalo. If he was passionate before, he became fanatic now.54 “He nearly killed Joe,” Lincoln recalled—with some satisfaction, for the boy did not care for that dour Canadian.55

Heading eastward into the rising sun, Roosevelt and his guide soon discovered the fresh spoor of a lone buffalo.56 For a while it was easy to follow, in earth still soft from rain; but as the day heated up, the ground baked hard, and the tracks dwindled to scratches. The hunters spent half an hour searching the dust of a ravine when suddenly

as we passed the mouth of a little side coulee, there was a plunge and crackle through the bushes at its head, and a shabby-looking old bull bison galloped out of it and, without an instant’s hesitation, plunged over a steep bank into a patch of rotten, broken ground which led around the base of a high butte. So quickly did he disappear that we had not time to dismount and fire. Spurring our horses we … ran to the butte and rode round it, only to see the buffalo come out of the broken land and climb up the side of another butte over a quarter of a mile off. In spite of his great weight and cumbersome, heavy-looking gait, he climbed up the steep bluff with ease and even agility, and when he had reached the ridge stood and looked back at us for a moment; while doing so he held his head high up, and at that distance his great shaggy mane and huge forequarter made him look like a lion.

This thrilling vision lasted only for a second; the buffalo was evidently used to the ways of hunters, and galloped off. Roosevelt and Ferris followed his trail for miles but never saw him again.

They found themselves now on the edge of the eastern prairie. “The air was hot and still, and the brown, barren land stretched out on every side for leagues of dreary sameness.” At about eleven o’clock they lunched by a miry pool, and then ambled on east, trying to conserve their horses in the midday heat. It was late in the afternoon before they saw three black specks in the distance, which proved to be buffalo bulls. The hunters left their horses half a mile off and began to wriggle like snakes through the sagebrush. Roosevelt blundered into a bed of cactus, and filled his hands with spines. At about 325 yards he drew up and fired at the nearest beast. Confused by its bulk and shaggy hair, he aimed too far back. There was a loud crack, a spurt of dust, “and away went all three, with their tails up, disappearing over a light rise in the ground.”

The hunters furiously ran back to their horses and galloped after the buffalo. Not until sunset did they catch up with them. By then their ponies were thoroughly jaded. Flailing with spurs and quirts, Roosevelt closed in on his wounded bull, as the last rays of daylight ebbed away. Fortunately for him, a full moon was rising, and he managed to move within twenty feet of the desperate animal. But the ground underfoot was so broken that his fagged horse could not canter smoothly. His first shot missed. The bull wheeled and charged.

My pony, frightened into momentary activity, spun round and tossed up his head; I was holding the rifle in both hands, and the pony’s head, striking it, knocked it violently against my forehead, cutting quite a gash … heated as I was, the blood poured into my eyes.57 Meanwhile the buffalo, passing me, charged my companion, and followed him as he made off, and, as the ground was very bad, for some little distance his lowered head was unpleasantly near the tired pony’s tail. I tried to run in on him again, but my pony stopped short, dead beat; and by no spurring could I force him out of a slow trot. My companion jumped off and took a couple of shots at the buffalo, which missed in the dim moonlight; and to our unutterable chagrin the wounded bull labored off and vanished into the darkness.

The critical thing now was to find water, both for themselves and for their mounts. They had had nothing to drink for at least nine hours. Roosevelt and Ferris led the foaming, trembling animals in search of moisture, and after much wandering found a mud-pool “so slimy that it was almost gelatinous.” Parched though they were, “neither man nor horse could swallow more than a mouthful of this water.” The night grew chill, and the prairie was too bare to provide even twigs for a fire. Each man ate a horn-hard biscuit (baked, rather too conscientiously, by Lincoln Lang).58 Then, wrapping themselves in blankets, they lay down to sleep. For pillows they used saddles, lariated—since there was no other tether—to the horses.

It was some time before they could doze off, for the horses kept snorting nervously and peering, ears forward, into the dark. “Wild beasts or some such thing, were about … we knew that we were in the domain of both white and red horse-thieves, and that the latter might, in addition to our horses, try to take our scalps.”

About midnight the hunters were brutally awoken by having their saddles whipped from beneath their heads. Starting up and grabbing their rifles, they saw the horses galloping frantically off in the bright moonlight. But there were no thieves to be seen. Only a shadowy, four-footed form in the distance suggested that a wolf must have come to inspect the camp, and terrified the horses into flight.

Following the dewy path left by the trailing saddles, they captured both animals, returned to camp, and resumed their interrupted slumbers. But then a cold rain began to fall, and they woke to find themselves lying in four inches of water. Shivering between sodden blankets, Ferris heard Roosevelt muttering something. To Joe’s complete disbelief, the dude was saying, “By Godfrey, but this is fun!”59

![]()

AFTER YET ANOTHER rainy day, so cold it turned Roosevelt’s lips blue, and another sunny one, so hot it peeled the skin off his face, even he was willing to return to Lang’s ranch and admit failure yet again. He had had an easy shot at a cow buffalo in the rain, but his eyes were so wet he could hardly draw a bead—“one of those misses which a man to his dying day always looks back upon with wonder and regret.”60 Then, in the heat, there had been a somersault that pitched him ten feet beyond his pony into a bed of sharp bushes, and a quicksand that half swallowed his horse.… “Bad luck,” remarked Joe Ferris afterward, “followed us like a yellow dog follows a drunkard.”61 But Roosevelt still insisted he was having “fun.” Indeed, he might well have continued the hunt indefinitely had he not had an important business decision to communicate to his host.

“I have definitely decided to invest, Mr. Lang. Will you take a herd of cattle from me to run on shares or under some other arrangement to be determined between us?”

The rancher was flattered, but regretfully declined. He was already tied to one financial backer, he said, and it would be disloyal to work for another man as well. “I am more than sorry.”

Swallowing his disappointment, Roosevelt asked Lang if he could suggest any other possible partners.

“About the best men I can recommend,” came the reply, “are Sylvane Ferris and his partner, Merrifield. I know them quite well and believe them to be good, square fellows who will do right by you if you give them a chance.”62

Roosevelt could not have been enchanted by the prospect of employing two grim Canadians who had looked askance at his spectacles, and had refused to lend him a horse; but he accepted Lang’s recommendation. Young “Link” was told to saddle up early next morning and ride to Maltese Cross to fetch them.63

![]()

MEANWHILE THE HUNT RESUMED. For two more rainy days Roosevelt and Joe combed the Badlands for buffalo, but the elusive animals were nowhere in sight. By now Ferris had come to the grudging conclusion that his client was “a plumb good sort.” Garrulous in the cabin, Roosevelt on the trail was quiet, purposeful, and tough. “He could stand an awful lot of hard knocks, and he was always cheerful.” The guide was intrigued by his habit of pulling out a book in flyblown campsites and immersing himself in it, as if he were ensconced in the luxury of the Astor Library. Most of all, perhaps, he was impressed by a casual remark Roosevelt made one night while blowing up a rubber pillow. “His doctors back East had told him that he did not have much longer to live, and that violent exercise would be immediately fatal.”64

Sylvane Ferris and Bill Merrifield were waiting for Roosevelt when he returned to Lang’s cabin on the evening of 18 September. After supper they all sat on logs outside and Roosevelt asked how much, in their opinion, it would cost to stock a cattle ranch adequately. The subsequent dialogue (transcribed by Hermann Hagedorn, from the verbal recollections of those present) went like this:

|

SYLVANE |

Depends what you want to do, but my guess is, if you want to do it right, it’ll spoil the looks of forty thousand dollars. |

|

ROOSEVELT |

How much would you need right off? |

|

SYLVANE |

Oh, a third would make a start. |

|

ROOSEVELT |

Could you boys handle the cattle for me? |

|

SYLVANE |

(drawling) Why, yes, I guess we could take care of ’em ’bout as well as the next man. |

|

MERRIFIELD |

Why, I guess so! |

|

ROOSEVELT |

Well, will you do it? |

|

SYLVANE |

Now, that’s another story. Merrifield here and me is under contract with Wadsworth and Halley. We’ve got a bunch of cattle with them on shares… |

|

ROOSEVELT |

I’ll buy those cattle. |

|

SYLVANE |

All right. Then the best thing for us to do is go to Minnesota an’ see those men an’ get released from our contract. When that’s fixed up, we can make any arrangements you’ve a mind to. |

|

ROOSEVELT |

(drawing a checkbook from his pocket) That will suit me. (Writes check for $14,000, hands it over.) |

|

MERRIFIELD |

(after a pause) Don’t you want a receipt? |

|

ROOSEVELT |

Oh, that’s all right. |

No photograph survives to record the expressions of the two Scots witnesses to this scene.65

Roosevelt was not by nature a businessman. His tendency to spend freely, and invest in dubious schemes on impulse, had long been a source of alarm to the more responsible members of his family, whose shrewd Dutch blood still ran strong.66 Indeed, as far as financial matters were concerned, Theodore was more of a Bulloch than a Roosevelt. Although he had inherited $125,000 from his father,67 and was due a further $62,500 when Mittie died, he had since college days lived as if he were twice as wealthy. In 1880, the year of his marriage, his income stood at $8,000, and he had no difficulty in spending every penny—lavishing $3,889 on wedding presents alone. “I’m in frightful disgrace with Uncle Jim,” he gaily confessed to Elliott, “on account of my expenditures, which certainly have been very heavy.”68 Yet he made no resolutions to be thrifty. Shortly after the success of The Naval War of 1812, he had written a check for $20,000 to buy himself a partnership with its publishers, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, but there was only half that amount in his bank at the time, and the check had bounced.69 He again incurred James Roosevelt’s wrath by investing $5,000 in the Cheyenne Beef Company, and had to be dissuaded from sinking a further $5,000 into Commander Gorringe’s enterprise. His total income for 1883, swelled by royalties, dividends, and his $1,200 salary as an Assemblyman, would amount to $13,920,70 yet, with three months of the year remaining, he had just written a check in excess of this amount. He must have had extra funds, for there is no record of the check being returned; still, financial caution was obviously not one of his outstanding characteristics.

Despite Gregor Lang’s insistence that the cattle business was “the best there is,” Roosevelt must have known he was taking a risk in investing in it. There were huge profits to be made, presumably, but huge expenditures came first, and it would be years before any returns came in. Small wonder that most investors in “the beef bonanza” were Eastern capitalists and European aristocrats, men who could afford to spend—and lose—millions. Roosevelt was a fairly wealthy young man, but his funds were puny in comparison with those of, say, the Marquis de Morès.

What then was the great dream which visibly possessed him during that September of 1883, and committed him to spending one-third of his patrimony in Dakota? It could not have been the mere making of money: as far as he was concerned, he already had enough. The clue may lie in an observation by Lincoln Lang.

Clearly I recall his wild enthusiasm over the Bad Lands … It had taken root in the congenial soil of his consciousness, like an ineradicable, creeping plant, as it were, to thrive and permeate it thereafter, causing him more and more to think in the broad gauge terms of nature—of the real earth.71

There was, in this beautiful country, something which thrilled Roosevelt, body and soul. As a child, hardly able to breathe in New York City, he had craved the sweet breezes of Long Island and the Hudson Valley. Here the air had the sting of dry champagne. All his life he had loved to climb mountains and gaze upon as much of the world as his spectacles could take in. Here he had only to saunter up a butte, and the panorama extended for 360 degrees. In recent years, he had spent much of his time in crowded, noisy rooms. Here he could gallop in any direction, for as long as he liked, and not see a single human being. Fourteen thousand dollars was a small price to pay for so much freedom.

![]()

IT WAS AGREED that while Sylvane and Merrifield journeyed to Minnesota to break their contract, Roosevelt would remain in the Badlands and await a confirming telegram.72 On 20 September the ranchers set off downriver, and he and Joe went in search of buffalo yet again. This time they rode west into Montana. About noon, their ponies began to snuff the air. Roosevelt dismounted, and, following the direction of his horse’s muzzle, ran cautiously up a valley. He peeped over the rim.

There below me, not fifty yards off, was a great bison bull. He was walking along, grazing as he walked. His glossy fall coat was in fine trim and shone in the rays of the sun, while his pride of bearing showed him to be in the lusty vigor of his prime. As I rose above the crest of the hill, he held up his head and cocked his tail to the air. Before he could go off, I put the bullet in behind his shoulder. The wound was an almost immediately fatal one, yet with surprising agility for so large and cumbersome an animal, he bounded up the opposite side of the ravine … and disappeared over the ridge at a lumbering gallop, the blood pouring from his mouth and nostrils. We knew he could not go far, and trotted leisurely along his bloody trail.…

And in the next gully they found their prize “stark dead.”73

Roosevelt now abandoned himself to complete hysteria. He danced around the great carcass like an Indian war-chief, whooping and shrieking, while his guide watched in stolid amazement. “I never saw anyone so enthused in my life,” said Ferris afterward, “and by golly, I was enthused myself … I was plumb tired out.” When Roosevelt finally calmed down, he presented the Canadian with a hundred dollars.74

Now they stooped to the “tedious and tiresome” ritual of hacking the bull’s huge head off, and slicing fillets of tender, juicy hump meat from either side of the backbone. Then, loading their ponies with the slippery cargo, they rode back home, chanting “paens of victory.”75

There was feasting that night in the Langs’ little cabin. The buffalo steaks “tasted uncommonly good … for we had been without fresh meat for a week; and until a healthy, active man has been without it for some time, he does not know how positively and almost painfully hungry for flesh he becomes.”76

On the morning of 21 September Roosevelt bade farewell to his hosts and began the fifty-mile trek back to Little Missouri, where he would await his telegram from Minnesota. As the buckboard rattled away, and Lincoln Lang caught his last flash of teeth and spectacles, he heard his father saying, “There goes the most remarkable man I ever met. Unless I am badly mistaken, the world is due to hear from him one of these days.”77