Heart’s dearest,

Why dost thou sorrow so?

![]()

THE STARS WERE ALREADY PALE in the east as he rode across the river-bottom and struck off up a winding valley.1 His horse, Manitou, loped effortlessly through a sea of sweet-smelling prairie-rose bushes. Presently the sun’s first rays rushed horizontally across the Badlands, kissing the tops of the buttes, and shocking millions of drowsy birds into song.

Among the swelling chorus of hermit thrushes, grosbeaks, robins, bluebirds, thrashers, and sparrows, Roosevelt’s acute ear caught one particularly rich and bubbling sound, with “a cadence of wild sadness, inexpressibly touching.”2 He identified it as the meadowlark. Ever afterward, the music of that bird would come “laden with a hundred memories and associations; with the sight of dim hills reddening in the dawn, with the breath of cool morning winds blowing across lowly plains, with the scent of flowers on the sunlit prairie.”3

Some varieties of birdsong, however much they ravished Roosevelt’s ear, aroused in his heart that same sharp, indefinable nostalgia which he had felt as a child, gazing at the portrait of Edith Carow.4 Ache though he may, he could not escape hearing them in Dakota, in June, a month of prodigious migrations. Nor did he really want to. For four years or more, he had been starved of this, the only kind of music he really understood. In abandoning his natural history studies for Alice Lee, he had stifled the precocious sensitivity to nature that was so characteristic of him as a youth. Now, as a twenty-five-year-old widower, with his second career abandoned—or at least indefinitely postponed—he could reopen his ears to the “sweet, sad songs” of the hermit thrush, the “boding call” of the whippoorwill, and “the soft melancholy cooing of the mourning-dove, whose voice always seems far away and expresses more than any other sound in nature the sadness of gentle, hopeless, never-ending grief.”5

“New York will certainly lose him for a time at least.”

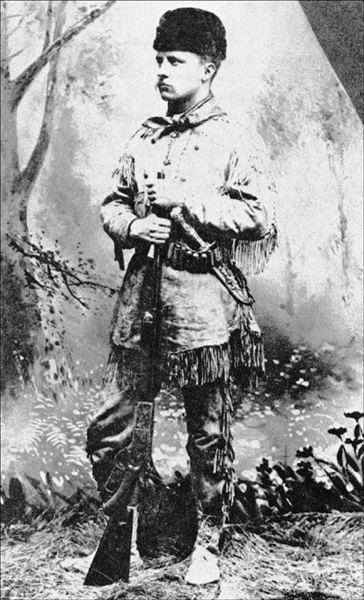

Theodore Roosevelt in his buckskin suit, 1884. (Illustration 11.1)

![]()

TWO MAGPIES, perched on a bleached buffalo skull,6 greeted him as he left the creek and rode through a line of scoria-red buttes. The naked prairie opened out ahead, already hot and shimmering under the climbing sun. Choosing one course at random, he headed south, scanning the horizon for antelope. All he carried, beside his rifle, was a book, a blanket, an oilskin, a metal cup, a little tea and salt, and some dry biscuits. Since arriving in Dakota nine days before, he had eaten nothing but canned pork and starch. Ferris and Merrifield were too busy with the spring roundup to shoot any fresh meat. Roosevelt therefore had good dietetic reasons, as well as his “boyish ambition,” for embarking on a trip across the prairie. But his real hunger was for solitude.

Nowhere, not even at sea, does a man feel more lonely than when riding over the far-reaching, seemingly never-ending plains … their vastness and loneliness and their melancholy monotony have a strong fascination for him. The landscape seems always the same, and after the traveller has plodded on for miles and miles he gets to feel as if the distance were really boundless. As far as the eye can see, there is no break; either the prairie stretches out into perfectly level flats, or else there are gentle, rolling slopes … when one of these is ascended, immediately another precisely like it takes its place in the distance, and so roll succeeds roll in a succession as interminable as that of the waves in the ocean. Nowhere else does one feel so far off from all mankind; the plains stretch out in deathless and measureless expanse, and as he journeys over them they will for many miles be lacking in all signs of life.7

Lonely, melancholy, monotony, deathless—these words, especially the first, became obsessive parts of Roosevelt’s vocabulary in 1884. There was, however, no shortage of his favorite adjective manly, and his favorite pronoun, I. While accepting that his first few days on the prairie must have had their moments of anguish (since Alice’s death he had not been alone for more than a few hours at a time), one cannot read his descriptions of the trip without sensing his overwhelming delight in being free at last. “Black care,” Roosevelt wrote, “rarely sits behind a rider whose pace is fast enough.”8

He sighted several small bands of antelope that morning. For hours he pursued them, first on foot, then on hands and knees, and finally flat on his face, wriggling through patches of cactus; but the nervous creatures were off before he could draw a bead. After a lunch of biscuits and water, and a snooze in the broiling sun—the only shade available was that of his own hat—he pushed on doggedly. Once horse and rider were very nearly engulfed in a quicksand, “and it was only by frantic strugglings and flounderings that we managed to get over.” Roosevelt learned to stay well clear of stands of tall grass in seemingly dry creeks: beneath might lurk a fathomless bed of slime.

He learned, too, that fleeing antelope have a quasi-military tendency to gallop in straight lines, even when intercepted at an angle. Taking advantage of this, he succeeded eventually in rolling over one fine buck “like a rabbit.” Cutting off the hams and head, and stringing them to his saddle, he rode on in search of a campsite. Around sunset he found a wooded creek with fresh pools and succulent grass. Turning Manitou loose to browse, Roosevelt lit a fire “for cheerfulness,” cut himself an antelope steak, and roasted it on aforked stick. Later he lay on his blanket under a wide-branching cottonwood tree, “looking up at the stars until I fell asleep, in the cool air.”9

![]()

THE SHRILL YIPPING of prairie dogs awoke him shortly before dawn. It was now very chill, and wreaths of light mist hung over the water. Roosevelt reached for his rifle and strolled through the dark trees out onto the prairie.

Nothing was in sight in the way of game; but overhead a skylark was singing, soaring above me so high that I could not make out his form in the gray morning light. I listened for some time, and the music never ceased for a moment, coming down clear, sweet, and tender from the air above. Soon the strains of another answered from a little distance off, and the two kept soaring and singing as long as I stayed to listen; and when I walked away I could still hear their notes behind me.10

On returning to the camp at sunrise, Roosevelt caught sight of a doe going down to the water, “her great, sensitive ears thrown forward as she peered anxiously and timidly around.” Gun forgotten, he watched enchanted while she drank her fill. She snatched some hasty mouthfuls of wet grass; presently a spotted fawn joined her. When they left, the pond was taken over by a mallard and her ducklings, “balls of fuzzy yellow down, that bobbed off into the reeds as I walked by.”11

![]()

ROOSEVELT WAS BACK at the Maltese Cross Ranch on 22 June, having spent five days in the wilderness, feeling “as absolutely free as any man could feel.”12 He might have stayed away longer, but he did not wish his venison to spoil in the hot sun. The little log cabin was deserted. Ferris and Merrifield had left for St. Paul, with $26,000 of his money, to purchase a thousand new head of cattle;13 they would not be back for another month. He felt too restless to settle down and begin the writing he had vaguely planned for summer. Next day he was in the saddle again, riding downriver.14

En route he stopped at Medora to pick up some mail, and was able to take his first good look around since returning to the Badlands.15 The hamlet of last fall, with its giant chimney and scattered, half-finished houses, was now a bustling town of eighty-four buildings, including a hotel which the Marquis de Morès had modestly named after himself. Little Missouri, meanwhile, was already slipping into ghosthood on the other side of the river. Trains no longer stopped there. Medora, clearly, was the future capital of the Badlands.16

A spirit of lusty optimism pervaded the place. Roosevelt, tethering Manitou and gazing about him, could not help but respond to it. The beef business was prospering; it had been a mild winter, and plenty of fat steers were ambling to their doom in the slaughterhouse. A record number of calves had been born to replace them—155 at Maltese Cross alone.17 Daily consignments of dressed meat were being shipped East by the Marquis’s Northern Pacific Refrigerator Car Company. Meanwhile, de Morès was spawning new business ideas with codfish-like fertility. He would plant fifty thousand cabbages in the Little Missouri Valley, and force-feed them with his own patented fertilizer, made from offal; he would run a stagecoach line along the eastern rim of the Badlands; he would invest $10,000 in a huge blood-drying machine; he would extend a chain of icehouses as far west as Oregon, so that Columbia River salmon could be whisked, cold and fresh, to New York in seven days; he would open a pottery in Medora to process the fine local clay; he would string a telegraph line all the way south to the Black Hills; he would supply the French Army with a delicious new soup he had invented.… As fast as these schemes flourished or failed, the Marquis would think of others.18

It is not definitely known whether Roosevelt met the Marquis in Medora that Monday, but they would have had difficulty avoiding each other. De Morès was the most ubiquitous person in town, given to riding up and down the street in a large white sombrero, his blue shirt laced with yellow silk cord, his mustaches prickling haughtily. Tall, wiry, and muscular, he sat his horse more gracefully than any cowboy.19 Gunmen treated him with scared respect: his reputation as a sharpshooter was exceeded only by the vivacious and redheaded Madame de Morès.20

Almost certainly the couple entertained Roosevelt with iced champagne, this being their invariable custom whenever a distinguished stranger came to town. The atmosphere may have been a little stiff at first, for there had been a dispute over grazing rights between the Marquis and Roosevelt’s cattlemen during the winter.21 But it is a matter of record that Roosevelt and de Morès were soon conferring on subjects of mutual interest, and planning a visit to Montana together.22

Before continuing his expedition downriver, Roosevelt dropped in at the office of Medora’s weekly newspaper, the Bad Lands Cowboy. Its editor, a bearded, flap-eared, engaging youth named Arthur Packard, had disquieting news. According to Eastern dispatches, much political vituperation was being lavished on the names Roosevelt and Lodge. The former’s railroad interview at St. Paul, stating that he had “no personal objections” to James G. Blaine, and the latter’s announcement, on returning to Boston, that he, too, would support the Chicago convention’s choice, had enraged the reform press.23 Clearly they had been expected to follow George William Curtis, and a host of other prominent Independents, out of the Republican party.

Roosevelt showed little interest, merely saying that the St. Paul reporter had misquoted him out of “asininity.”24 Politics must have seemed impossibly remote and irrelevant in Packard’s whitewashed, inky-smelling office, with its slugs of type spelling out news of more immediate interest, to do with horse-thievery and the price of fresh manure.25

Remounting Manitou, Roosevelt rode out of Medora and headed north into the green bottomlands of the Little Missouri.

![]()

THE NEXT ISSUE OF the Bad Lands Cowboy briefly reported that a new dude had arrived in town.

Theodore Roosevelt, the young New York reformer, made us a very pleasant call Monday, in full cowboy regalia. New York will certainly lose him for a time at least, as he is perfectly charmed with our free Western life and is now figuring on a trip into the Big Horn country …26

![]()

WHEN PACKARD’S NEWS ITEM appeared, Roosevelt was at least thirty miles north, well beyond the farthest reach of ranch settlement. He was looking for “untrodden ground” on which to build a ranch house. The Maltese Cross log cabin, situated only eight miles south of Medora, did not satisy his present hunger for solitude. A popular pony-trail passed within a few yards of the front door; ten or twelve cowpunchers galloping by every week amounted, as far as he was concerned, to an intolerable amount of traffic noise. Worse still, at least half of them wanted to stop off and pass the time of day.27 How could a man write with so many interruptions? He wanted to live where the peace of nature was total.

Acting on a tip from a friendly cattleman, Roosevelt kept splashing across the meandering river, heading directly north until he reached a magnificent stretch of bottomland on the left bank. Grass spread smoothly back from the water’s edge for a hundred yards, merging into a belt of immense cottonwood trees. This bird-loud grove extended a farther two hundred yards west. Then a range of clay hills, which seemed to have been sculpted by a giant hand as preparatory studies for mountains, loomed steeply into the sky. A distant plume of lignite smoke, glowing pink as evening came on, hinted at the surrounding savagery of the Badlands. No place could be more remote from the world, yet more insulated from the wilderness.28 Roosevelt knew he had found his “hold” in Dakota.

Here he would build “a long, low ranch house of hewn logs, with a verandah, and with in addition to the other rooms, a bedroom for myself, and a sitting-room with a big fireplace.” There would be a rough desk, well stocked with ink and paper, two or three shelves full of books, and a rubber tub to bathe in. Out front, on a piazza overlooking the river, there would be the inevitable Rooseveltian rocking-chair, in which he could sit reading poetry on summer afternoons, or watching his cattle plod across the sandbars. At night, when he came back tired and bloody from hunting, there would be a welcoming flicker of firelight through the cottonwood trees, plenty of fresh meat to eat, and beds spread with buffalo robes.…29

Of course several practical things had to be done before these dreams were realized. He must first claim the site (the presence of a hunting shack nearby meant he would probably have to buy squatter’s rights);30 he must order many more cattle; he must hire men to build the house and run the ranch for him. As it happened, he already had two recruits for the latter job: his two old friends from the backwoods of Maine, Bill Sewall and Wilmot Dow.

![]()

ON 9 MARCH 1884—less than three weeks after burying Alice—Roosevelt had written to Sewall with a rather peremptory invitation to join him in Dakota. “I feel sure you will do well for yourself by coming out with me … I shall take you and Will Dow out next August.”31 What persuaded him that a pair of forest-bred Easterners would flourish in the Badlands is unclear, but Sewall and Dow were agreeable. Their motives appear to have been pecuniary. “He said he would guarantee us a share of anything made in the cattle business,” Sewall recalled. “And if anything was lost, he would lose it and pay our wages … I told him that I thought it was very onesided, but if he thought he could stand it, I thought we could.”32 There were minor hindrances, such as mortgages and protesting wives, but Roosevelt settled the former with a check for $3,000, and assured Mrs. Sewall and Mrs. Dow that they could come West in a year, if all went well.33

Within a few days of discovering the downriver ranch-site in June, he purchased full rights to both shack and land for $400.34 Before returning East to pick up Sewall and Dow, he found time to make his scheduled visit to Montana with the Marquis de Morès.35The date of this trip was deliberately kept secret, but 26 June seems likely. The Marquis would have found it prudent to be out of town that day, since it was the first anniversary of Riley Luffsey’s murder.

The two young men wished to sign on as members of a band of vigilantes, or “stranglers,” which had just been organized in Miles City, its purpose being to lynch the horse-thieves currently plaguing the Dakota-Montana border. Fortunately for Roosevelt’s subsequent political reputation, their application was refused. Granville Stuart, leader of the vigilantes, told them that they were too “socially prominent” to belong to a secret society.36

On 1 July Roosevelt left Medora for New York.37

![]()

HE FOUND BABY LEE, all blue eyes and blond curls, living with Bamie at 422 Madison Avenue. Henceforth this house would be his pied-à-terre on visits to New York—although Bamie was not keen on the idea of brother and sister sharing the same town address.38Much as she loved to look after him, she was afraid they might drift into a cozy, quasi-marital relationship centering around her quasi-daughter. Bamie was a person of fine instinct and disciplined emotions, unlike Corinne, who could never see enough of her “Teddy,” and for whom he could never do wrong.39

But Bamie need not have worried. Roosevelt showed no desire to remain at No. 422 a moment longer than necessary. Sewall and Dow were ordered to fix up their affairs “at once” and hurry to New York, so that they could leave for Dakota by the end of the month.40 Then Roosevelt took the ferry to New Jersey for a few days with Corinne. He seemed anxious to stay away from his daughter, who was now almost five months old. (Since going to Dakota he had not asked a single question about the child in his letters home.) No record remains of their reunion. It is known, however, that after leaving New Jersey he took little Alice to Boston to see her grandparents.41 The visit cannot have been cheerful. At the soonest possible moment he fled Chestnut Hill for Nahant, Henry Cabot Lodge’s summer place.42

A sentence in one of Aunt Annie Gracie’s letters provides a clue, perhaps, to Roosevelt’s curious terror of Baby Lee: “She is a very sweet pretty little girl, so much like her beautiful young Mother in appearance.”43

![]()

NOR WAS THIS his only phobia that summer. In New York, Bamie was told to warn him if a certain old family friend came to call, so that he could arrange to be absent.44 As a married man, he had been able to withstand the cool blue eyes of Edith Carow; but now, widowed and alone, it was as if he feared they might once again find him childishly vulnerable.

![]()

ON 11 JULY the Democratic National Convention nominated Grover Cleveland for President of the United States. The Governor was in Albany, working as usual, when at 1:45 P.M. the dull booming of cannons floated through the windows of his office. An aide tried to congratulate him. “They are firing a salute, Governor, for your nomination.”

“Do you think so? Well, anyhow, we’ll finish up this work.”45

![]()

ROOSEVELT FOUND LODGE depressed during his short stay at Nahant. The extent to which Independent revulsion had gathered against James G. Blaine—and, by extension, against Lodge for supporting him—must have amazed them both. Almost to a man, the intellectual and social aristocracy of Massachusetts had decided to vote for Cleveland. The list of Republican opponents to Blaine contained such names as Adams, Quincy, Lowell, Saltonstall, Everett, and Eliot. These were the same names which had so often been borne on a silver tray into Lodge’s parlor. Now, suddenly, the tray was empty, and his friends were snubbing him in the street. Lodge confessed that supporting Blaine was “the bitterest thing I ever had to do in my life.” What particularly hurt was the widespread assumption that he had sold his conscience for a Congressional nomination in the fall.46

It was time, Roosevelt decided, to come to the aid of his stricken friend. He himself had said nothing publicly since his confession of support for Blaine at St. Paul, except to telegraph an ambiguous denial of the interview from Medora.47 No sooner had he returned to Chestnut Hill on 19 July than he summoned a reporter from the Boston Herald and announced, once and for all, that he, too, would support the Republican presidential ticket.

While at Chicago I told Mr. Lodge that such was my intention; but before announcing it, I wished to have time to think the whole matter over. A man cannot act both without and within the party; he can do either, but he cannot possibly do both …

I am by inheritance and education a Republican; whatever good I have been able to accomplish in public life has been accomplished through the Republican party; I have acted with it in the past, and wish to act with it in the future; I went as a regular delegate to the Chicago convention, and I intend to abide by the outcome of that convention. I am going back in a day or two to my Western ranches, as I do not expect to take any part in the campaign this fall.48

He arrived back in New York to find Bamie’s doormat piled with abusive letters. “Most of my friends seem surprised to find that I have not developed hoofs and horns,” he wryly told Lodge.49 Harder to take, perhaps, was the criticism of Alice’s family, voiced by her uncle, Henry Lee: “As for Cabot Lodge, nobody’s surprised at him; but you can tell that young whipper-snapper in New York from me that his independence was the only thing in him we cared for, and if he has gone back on that, we don’t care to hear any more about him.”50

Reform newspapers, whose hero Roosevelt had so recently been, were loud in their denunciations of him. The Evening Post thundered that “no ranch or other hiding place in the world” could shelter a so-called Independent who voted for the likes of James G. Blaine. Roosevelt sent a mischievous message to the editor, Edwin L. Godkin, accusing him of suffering from “a species of moral myopia, complicated with intellectual strabismus.” Godkin, who was a man of little humor, forthwith became his severest public critic.51

Roosevelt did not seem to mind his sudden unpopularity. When the rumor that Grover Cleveland was the father of a bastard flashed across the country on 21 July,52 he could afford to laugh at the Independents who had already bolted to the Governor’s side. Although he seemed, in a final interview on 26 July, to be talking only about his life out West, he subtly sounded a favorite theme: that of the masculine hardness of the practical politician, as opposed to the effeminate softness of armchair idealists.

It would electrify some of my friends who have accused me of representing the kid-glove element in politics if they could see me galloping over the plains day in and day out, clad in a buckskin shirt and leather chaparajos, with a big sombrero on my head. For good healthy exercise I would strongly recommend some of our gilded youth to go West and try a short course of riding bucking ponies, and assist at the branding of a lot of Texas steers.53

With that the ex-Assemblyman boarded a train with Sewall and Dow and returned to Dakota.

![]()

“WELL, BILL, WHAT do you think of the country?” asked Roosevelt. It was 1 August 1884, and the two backwoodsmen were spending their first night in the Badlands, at the Maltese Cross Ranch.

“I like it well enough,” said Sewall, “but I don’t believe that it’s much of a cattle country.”

“You don’t know anything about it,” Roosevelt protested.

Sewall obstinately went on: “It’s the way it looks to me, like not much of a cattle country.”54

Roosevelt shrugged off this remark. With a thousand new head just arrived from Minnesota (“the best lot of cattle shipped west this year,” said the Bad Lands Cowboy) and six hundred veterans of last winter browsing contentedly on the river, he could see no reasons for pessimism.55 The next morning he ordered Sewall and Dow north to the downriver ranch-site, with a hundred head “to practice on.” They left under the supervision of a grumpy herder, who was doubtful about Sewall’s capacity to stay on his horse. Sewall, jouncing along uncomfortably, allowed that he had more experience “riding logs.”56

Roosevelt remained behind. There was a certain amount of soothing to be done at Maltese Cross. Merrifield and Ferris had not been pleased to discover, on returning from St. Paul, that a couple of Eastern lumbermen had displaced them in the boss’s esteem. Since Roosevelt intended to build his home-ranch downriver, and would spend most of his time there, it was obvious whose company he preferred. Merrifield in particular was a man of easily bruised ego: perhaps to mollify him, Roosevelt asked if he would be his guide in a major hunting expedition later that month.57

This was the “trip into the Big Horn country” of Wyoming that he had been excitedly planning since June. “You will probably not hear from me for a couple of months,” he warned Bamie, adding with relish, “… if our horses give out or run away, or we get caught in the snow, we may be out very much longer—till towards Christmas.”58 He stopped short of telling his nervous sister that he had set his heart on killing the most dangerous animal in North America—the Rocky Mountain grizzly bear.

He wanted to leave within two weeks, but extra ponies had to be found and he was forced to postpone his departure to 18 August. In the interim he roamed restlessly through the Badlands, riding thirty miles south to visit the Langs, and forty miles north to check up on “my two backwoods babies.” Exploring his new property with Sewall, he came upon the skulls of two elks with interlocked antlers. “Theirs had been a duel to the death,” he decided. It was just the sort of symbol to appeal to him, and he promptly named the ranch-site Elkhorn.59

Apart from a touch of diarrhea, brought on by the alkaline water of the Little Missouri, Sewall and Dow seemed to be adjusting well to Dakota, and enjoying their new work. During the day they worked at making Roosevelt’s hunting-shack habitable (it would serve as a home until the big ranch house was built), and at night took turns in watching the herd. Sewall still had misgivings about the Badlands as cattle country, while admitting that its “wild, desolate grandeur … has a kind of charm.”60

Roosevelt used almost the same words in his letter to Bamie of 12 August.

… I grow very fond of this place, and it certainly has a desolate, grim beauty of its own, that has a curious fascination for me. The grassy, scantily wooded bottoms through which the winding river flows are bounded by bare, jagged buttes; their fantastic shapes and sharp, steep edges throw the most curious shadows, under the cloudless, glaring sky; and at evening I love to sit out in front of the hut and see their hard, gray outlines gradually growing soft and purple as the flaming sunset by degrees softens and dies away; while my days I spend generally alone, riding through the lonely rolling prairie and broken lands.61

He spent whole days in the saddle, riding as many as seventy-two miles between dawn and darkness. Sometimes he rode on through the night, rejoicing in the way “moonbeams play over the grassy stretches of the plateaus and glance off the windrippled blades as they would from water.”62 His body hardened, the tan on his face deepened, hints of gold appeared in his hair and reddish mustache. “I now look like a regular cowboy dandy, with all my equipments finished in the most expensive style,” he wrote Bamie. His buckskin tunic, custom-tailored by the Widow Maddox, seamstress of the Badlands, gave him particular delight, although its resemblance to a lady’s shirtwaist caused some comment in Medora. “You would be amused to see me,” he accurately wrote to Cabot Lodge, “in my broad sombrero hat, fringed and beaded buckskin shirt, horse hide chaparajos or riding trousers, and cowhide boots, with braided bridle and silver spurs.”63

It was probably during these seventeen free-ranging days that Roosevelt had his famous encounter with a bully in Nolan’s Hotel, Mingusville, thirty-five miles west of Medora.64 The incident, which has since become a cliché in a thousand Wild West yarns, is best told in his own words:

I was out after lost horses … It was late in the evening when I reached the place. I heard one or two shots in the bar-room as I came up, and I disliked going in. But there was nowhere else to go, and it was a cold night. Inside the room were several men, who, including the bartender, were wearing the kind of smile worn by men who are making believe to like what they don’t like. A shabby individual in a broad hat with a cocked gun in each hand was walking up and down the floor talking with strident profanity. He had evidently been shooting at the clock, which had two or three holes in its face.

… As soon as he saw me he hailed me as “Four Eyes”, in reference to my spectacles, and said, “Four Eyes is going to treat.” I joined in the laugh and got behind the stove and sat down, thinking to escape notice. He followed me, however, and though I tried to pass it off as a jest this merely made him more offensive, and he stood leaning over me, a gun in each hand, using very foul language … In response to his reiterated command that I should set up the drinks, I said, “Well, if I’ve got to, I’ve got to,” and rose, looking past him.

As I rose, I struck quick and hard with my right just to one side of the point of his jaw, hitting with my left as I straightened out, and then again with my right. He fired the guns, but I do not know whether this was merely a convulsive action of his hands, or whether he was trying to shoot at me. When he went down he struck the corner of the bar with his head … if he had moved I was about to drop on my knees; but he was senseless. I took away his guns, and the other people in the room, who were now loud in their denunciation of him, hustled him out and put him in the shed.

Next morning Roosevelt heard to his satisfaction that the bully had left town on a freight train.65

![]()

ANOTHER THREAT, from a more powerful adversary, arrived at Elkhorn one day in the form of a letter from the Marquis de Morès. It coolly announced that Roosevelt had no title to the land around his ranch-site. In the summer of 1883 the Marquis had stocked it with twelve thousand sheep; therefore the range belonged to him.66

Like most Americans, Roosevelt had a profound contempt for sheep. Not only did the “bleating idiots” nibble the grass so short that they starved out cattle, they were, intellectually speaking, about the lowest level of brute creation. “No man can associate with sheep,” he snorted, “and retain his self-respect.”67 In any case, the Marquis’s flock had not survived the winter. Roosevelt curtly informed de Morès, by return messenger, that only dead sheep remained on the range, and he “did not think that they would hold it.”

There was no reply, but Sewall and Dow were warned to look out for trouble.68

![]()

ONE MELANCHOLY DUTY awaited Roosevelt before he set off for the Big Horns on 18 August: the collation of some tributes, speeches, and newspaper clippings into a printed memorial for Alice Lee.69 Having arranged them as best he could, he added his own poignant superscription, under the heading “In Memory of my Darling Wife.”

She was beautiful in face and form, and lovelier still in spirit; as a flower she grew, and as a fair young flower she died. Her life had always been in the sunshine; there had never come to her a single great sorrow; and none ever knew her who did not love and revere her for her bright, sunny temper and her saintly unselfishness. Fair, pure, and joyous as a maiden; loving, tender, and happy as a young wife; when she had just become a mother, when her life seemed to be but just begun, and when the years seemed so bright before her—then, by a strange and terrible fate, death came to her.

And when my heart’s dearest died, the light went from my life forever.

The manuscript was sent to New York for private publication and distribution.70 Roosevelt sank briefly back into total despair. Gazing across the burned-out landscape of the Badlands, he told Bill Sewall that all his hopes lay buried in the East. He had nothing to live for, he said, and his daughter would never know him: “She would be just as well off without me.”

Talking as to a child, Sewall assured him that he would recover. “You won’t always feel as you do now and you won’t always be willing to stay here and drive cattle.”

But Roosevelt was inconsolable.71

![]()

A MONTH LATER, his mood had improved considerably. “I have had good sport,” he wrote Bamie, on descending from the Big Horn Mountains, “and enough excitement and fatigue to prevent overmuch thought.” He added significantly, “I have at last been able to sleep well at night.”72

Readers of Roosevelt’s diary of the hunt might wonder if by “excitement” he did not mean “carnage.” A list culled from the pages of this little book indicates just how much blood was needed to blot out “thought.” (Since Alice’s death his diaries had become a monotonous record of things slain.)

17 Aug. “My battery consists of a long .45 Colt revolver, 150 cartridges, a no. 10 choke bore, 300-cartridge shotgun; a 45–75 Winchester repeater, with 1,000 cartridges; a 40–90 Sharps, 150 cartridges; a 50–150 double barrelled Webley express, 100 cartridges.”

19 Aug. 4 grouse, 5 duck.

20 Aug. 1 whitetail buck, “still in velvet,” 2 sage hens.

24 Aug. “Knocked the heads off 2 sage grouse.”

25 Aug. 6 sharptail grouse, 2 doves, 2 teal.

26 Aug. 8 prairie chickens.

27 Aug. 12 sage hens and prairie chickens, 1 yearling whitetail “through the heart.”

29 Aug. “Broke the backs” of 2 blacktail bucks with a single bullet.

31 Aug. 1 jack rabbit, “cutting him nearly in two.”

3 Sept. 2 blue grouse.

4 Sept. 2 elk.

5 Sept. 1 red rabbit, 1 blue grouse.

7 Sept. 2 elk, 1 blacktail doe.

8 Sept. Spares a doe and two fawns, “as we have more than enough meat.” Kills 12 grouse instead.

11 Sept. 50 trout.

12 Sept. 1 bull elk, “killing him very neatly … knocked the heads off 2 grouse.”

13 Sept. 1 blacktail buck “through the shoulder,” 1 grizzly bear “through the brain.”

14 Sept. 1 blacktail buck, 1 female grizzly, 1 bear cub, “the ball going clean through him from end to end.”

15 Sept. 4 blue grouse.

16 Sept. 1 bull elk—“broke his back.”

17 Sept. “Broke camp … Three pack ponies laden with hides and horns.”73

Heading back to Dakota with his stinking cargo, Roosevelt killed a further 40 birds and animals on the prairie, making his total bag 170 items in just 47 days.74

So much for “excitement.” As to “fatigue,” he punished himself more severely, during these seven weeks, than ever before in his life. He covered nearly a thousand miles in the saddle and on foot, scorning a “prairie schooner” which accompanied him most of the way. The weather was often brutal, with winds powerful enough to overturn the wagon, and huge hailstones thudding into the earth with the velocity of bullets; but Roosevelt seemed to glory in it, once riding off alone into the rain. He camped in the Big Horns at altitudes of well over eight thousand feet, and at temperatures of well below freezing. Yet for all the thin air in his lungs and the chill in his bones, he pursued elk and bear with the energy of a hardened mountain-man:

We had been running briskly [after elk] uphill through the soft, heavy loam, in which our feet made no noise but slipped and sank deeply; as a consequence, I was all out of breath and my hand so unsteady that I missed my first shot … I doubt if I ever went through more violent exertion than in the next ten minutes. We raced after them at full speed, opening fire; I wounded all three, but none of the wounds were immediately disabling. They trotted on and we panted afterward, slipping on the wet earth, pitching headlong over charred stumps, leaping on dead logs that broke beneath our weight, more than once measuring our full length across the ground, halting and firing whenever we got a chance. At last one bull fell; we passed him by after the others, which were still running uphill. The sweat streamed into my eyes and made furrows in the sooty mud that covered my face, from having fallen full length down the burnt earth; I sobbed for breath as I toiled at a shambling trot after them, as nearly done out as could well be.

He kept on going until he had killed the second elk, and pursued the third until “the blood grew less, and ceased, and I lost the track.”75

Assuredly all this activity left Roosevelt little time to brood. Yet there was at least one final throb of grief. One night in the Big Horns, as bull elks trumpeted their wild, silvery mating-calls,76 he blurted out to Merrifield the details of his wife’s death. He said that his pain was “beyond any healing.” When Merrifield, who was also a widower, mumbled the conventional response, Roosevelt interjected, “Now don’t talk to me about time will make a difference—time will never change me in that respect.”77

![]()

ON 13 SEPTEMBER, a nine-foot, twelve-hundred-pound grizzly reared up not eight paces in front of him:

Doubtless my face was pretty white, but the blue barrel was as steady as a rock as I glanced along it until I could see the top of the bead fairly between his two sinister-looking eyes; as I pulled the trigger I jumped aside out of the smoke, to be ready if he charged; but it was needless, for the great brute was struggling in the death agony … the bullet hole in his skull was as exactly between his eyes as if I had measured the distance with a carpenter’s rule.78

Feeling calm and purged, Roosevelt suddenly decided he would, after all, go back East to vote. He might even take part in the last few weeks of the campaign, and make a speech or two for Henry Cabot Lodge. In a letter to Bamie, written at Fort McKinney, Wyoming, on 20 September, he gave his first hint of paternal yearnings for Baby Lee: “I hope Mousiekins will be very cunning: I shall dearly love her.”79

Impatience began to gather as the expedition creaked slowly homeward over three hundred miles of barren prairie. On 4 October, with seventy-five miles still to go, Roosevelt could stand the pace no longer. Leaving the wagon and extra ponies in care of his driver, he and Merrifield rode the remaining distance non-stop, by night.80

He allowed himself just one day to recover (having been in the saddle, almost continuously, for twenty-four hours) before riding another forty miles north to visit Sewall and Dow.81 They had unpleasant news for him: his forebodings of “trouble,” after rejecting the Marquis’s claim to the Elkhorn range, had been justified. E. G. Paddock—now more and more the power behind the throne of de Morès—had stopped by the ranch-site in late September, accompanied by several drunken gunmen. Finding Roosevelt away, the gang accepted lunch, sobered up, and rode off well stoked with beans and bonhomie. Since then, however, Paddock had begun to declare that the Elkhorn shack was rightfully his. If “Four Eyes” wished to buy it, he must pay for it in dollars—or in blood. Roosevelt, on hearing this, merely said, “Is that so?”82

Remounting his horse, he rode back upriver to Paddock’s house at the railroad crossing. The gunman answered his knock. “I understand that you have threatened to kill me on sight,” rasped Roosevelt. “I have come over to see when you want to begin the killing.”

Paddock was so taken aback he could only protest that he had been “misquoted.”83 Next morning Roosevelt left for New York, confident that from now on his ranch-site would be left in peace.

![]()

ON 11 OCTOBER, a Sun reporter found the former Assemblyman pacing restless and ruddy-faced around the library of 422 Madison Avenue, a glass of sherry in his hand, anxious to discuss campaign politics. “It is altogether contrary to my character,” Roosevelt explained, with the frankness that endeared him to all newspapermen, “to occupy a neutral position in so important and so exciting a struggle.” He added, rather wistfully, that it was “duty,” not ambition, that brought him back East. “I myself am not a candidate for any office whatsoever—for the present at least.” The reporter pressed for a comment on Grover Cleveland, and elicited the following exchange, in which Roosevelt’s moral disdain for the Governor shone clear:

Q. What do you think of Mr. Cleveland as a candidate for President of the United States?

A. I think that he is not a man who should be put in that office, and there is no lack of reasons for it. His public career, in the first place, and then private reasons as well. Of these personal questions I will not speak unless forced to, as Mr. Cleveland has always treated me with the utmost courtesy. But if, as I said, it should become necessary for me to discuss personal objections…84

During his seven subsequent campaign speeches—delivered between 14 October and 3 November, mainly in New York and in Lodge’s Massachusetts constituency—Roosevelt avoided the ugly accusations of debauchery which Republicans everywhere were flinging at Cleveland. Respect for that decent gentleman still lurked within him. He managed, however, to make at least one sanctimonious reference to “the immorality of breaking the seventh commandment.”85

Innuendo of this sort, from a man as genuinely puritanical as Roosevelt, might have been acceptable had it not been flavored with hypocrisy. Cleveland’s sexual peccadillo signified little, in national opinion. The Governor had made no attempt to hide the details, and the scandal had begun to die down.86 On the other hand, Blaine’s sins, as a Speaker who had used the powers of office to promote his own portfolio, could not be easily forgotten. There was no question as to which candidate was the morally inferior. Roosevelt’s statement that he was a Republican, and therefore bound to support Blaine, was understandable. Yet it could have been made in a letter from Dakota, rather than repeated ad nauseam all over the East, on platforms festooned with portraits of a man he despised.87

In later years, Roosevelt’s support of the Plumed Knight proved to be something of an embarrassment to his admirers, including that most ardent of them, himself. Nobody has ever satisfactorily reconciled Roosevelt’s passionate antagonism to Blaine in May and June with his equally passionate partisanship in October and November, although it has been argued that in bowing to the will of the party he was simply acting as a complete political professional.88 His many statements of support and non-support, his promises of action and threats of inaction, were bewilderingly self-contradictory. No adulterer could more adroitly combine illicit lovemaking with matrimonial obligations than Roosevelt in his relations with both wings of the party in 1884. While seducing the Independents, he promised to remain faithful to the Stalwarts; after abandoning the former, he assured them it was not out of love for the latter.

In his defense it must be said that he never sounded insincere. He genuinely believed that an Edmunds might represent the “good” in politics, but that only a Blaine, as President, could effectively bring that “good” about. Still it is hard to avoid the conclusion of one disgusted classmate: “The great good, of course, was Teddy.”89

![]()

ON 20 OCTOBER Roosevelt was annoyed to read a report, by one Horace White, of his off-the-record, post-convention remarks in a Chicago hotel five months before. White, it turned out, was the journalist to whom he had blustered, late on the night of Blaine’s nomination, that “any proper Democratic nomination will have our hearty support.” In an obvious attempt to expose Roosevelt as a turncoat, White chose to report the interview now, when the ex-Assemblyman was back in the public eye; to make the blow more personal, he did so in the correspondence columns of The New York Times. Roosevelt could do little but protest in a letter of reply that “I was savagely indignant at our defeat … and so expressed myself in private conversation.” He had “positively refused” to say anything for publication, “nor did I use the words that Mr. White attributes to me.”90 But the damage to his reputation had been done.

He consoled himself, in Boston, with the society of such intellectuals as William Dean Howells, Thomas Bailey Aldrich, and Oliver Wendell Holmes. These men came to a dinner at Lodge’s in honor of Roosevelt’s twenty-sixth birthday, and he glowed in the radiance of their conversation. “I do not know when I have enjoyed a dinner so much.”91

As the campaign entered its final week, Blaine seemed poised for inevitable victory. His extraordinary personal magnetism had never been stronger. Audiences everywhere serenaded him with adoring choruses of “We’ll Follow Where the White Plume Waves.” The stolid Cleveland, meanwhile, droned on about the tariff and Civil Service Reform, trying to ignore catcalls of “Ma! Ma! Where’s My Pa? Gone to the White House, Ha Ha Ha!”92

Then, in New York on 29 October, a garrulous Presbyterian minister, with Blaine standing at his side, publicly accused the Democratic party of representing “rum, Romanism, and rebellion.” The candidate, who was only half-listening, did not react to this faux pas, and therefore seemed to condone it. An alert bystander reported the phrase to Cleveland headquarters, just one block away. Within hours it had been telegraphed to every Democratic newspaper in the country. Headlines and handbills amplified the insult a millionfold. Overnight Blaine’s support among anti-prohibitionists, Catholics, and Southerners shrank away. In New York alone he lost an estimated fifty thousand votes.93 On Election Day, 4 November, Grover Cleveland became the nation’s first Democratic President in a quarter of a century.

![]()

IN A LETTER OF CONDOLENCE to Henry Cabot Lodge, whose bid for Congress had received a humiliating rejection in the polls, Roosevelt raged against “the cursed pharisaical fools and knaves who have betrayed us.”94 Evidently he ascribed the Republican defeat to Independent defectors, although every other political commentator in the country blamed it on the Presbyterian minister. The fact that he and Lodge had helped muster the Independents at Chicago, only to fall in behind the regular Republicans later, did not seem to indicate any betrayal on their part.

But three days after this letter to Lodge, he wrote a mea culpa which shows that all his essential decency and common sense had returned, if not yet his optimism.

Of course it may be true that we have had our day; it is far more likely that this is true in my case than yours … Blaine’s nomination meant to me pretty sure political death if I supported him; that I realized entirely, and went in with my eyes open. I have won again and again; finally chance placed me where I was sure to lose whatever I did; and I will balance the last against the first … I shall certainly not complain. I have not believed and do not believe that I shall ever be likely to come back into political life; we fought a good winning fight when our friends the Independents were backing us; and we have both of us, when circumstances turned them against us, fought the losing fight grimly out to the end. What we have been cannot be taken away from us; what we are is due to the folly of others; and to no fault of ours.95

In larger retrospect it may be seen that Roosevelt had done exactly the right thing, obeying the dictates of a political instinct so profound as to be almost infallible. He did not realize his luck, as he miserably returned to Dakota, but a Republican victory might have destroyed his chances of ever becoming President. The grateful Blaine would have offered him a government post, along with all the machine men who supervised the campaign; Roosevelt would thereafter have been associated with the corrupt Old Guard of the nineteenth century, rather than the enlightened Progressives of the twentieth. His decision not to “bolt” after Chicago was equally fortunate. Cleveland would not likely have rewarded him, and later Republican conventions would remember him as a man of doubtful loyalty.

All in all, a Republican defeat was the best thing that could have happened to Roosevelt in 1884. The fact that three alliterative words brought about that defeat only reinforces the conclusion that fate, as usual, was on his side. Not that he could be persuaded to seeit that way. “The Statesman (?) of the past,” he wrote Lodge from Maltese Cross, “has been merged, alas I fear for good, in the cowboy of the present.”96

![]()

ON 16 NOVEMBER, a spell of “white weather” settled down over the Badlands, as Roosevelt left his southern ranch and headed north to Elkhorn. His progress was slow that morning, for he had a beef herd to deliver to Medora. It was almost two o’clock before he concluded his business in town and rode on alone, with thirty-three miles to go.97

The wind in his face was achingly cold, especially on exposed plateaus when it combed grains of snow out of the grass and hurled them at him; the sensation was not unlike being whipped with sandpaper. His lungs (still occasionally troubled by asthma) gasped with every frigid breath, and his eyes throbbed in the glare of the sun. Descent into sheltered bottoms afforded some relief, but he took his life in his hands whenever he rode across the river. The ice was not yet solid. Should Manitou break through and douse him, it would be a serious matter, “for a wetting in such weather, with a long horseback journey to make, is no joke.”

Darkness surprised him when he was scarcely halfway to his destination. For a while he cantered along in the starlight, listening to the muffled drumming of his horse’s hooves, and “the long-drawn, melancholy howling of a wolf, a quarter of a mile off.” Clouds soon reduced visibility to zero, and he was forced to seek shelter in an empty shack by the river. There was enough wood round about to build a roaring fire, but no food to cook; all he had was a paper of tea-leaves and some salt. “I should have liked something to eat, but as I did not have it, the tea did not prove such a bad substitute for a cold and tired man.”

At dawn Roosevelt woke to the hoarse clucking of hundreds of prairie-fowl. Sallying forth with his rifle, he shot five sharptails. “It was not long before two of the birds, plucked and cleaned, were split open and roasted before the fire. And to me they seemed most delicious food.”98

Exactly one month before he had been campaigning on the platform of Chickering Hall in New York, twisting his eyeglasses, catching bouquets, and blushing under the admiring gaze of bejeweled society matrons.99

![]()

SEWALL AND DOW were felling trees for the ranch house when he galloped down into the Elkhorn bottom a few hours later.100 He seized an ax to assist them, much to their secret amusement, for Roosevelt was no lumberman. At the end of that day, he was chagrined to overhear Dow report to a cowpuncher: “Well, Bill cut down fifty-three, I cut forty-nine, and the boss, he beavered down seventeen.”

“Those who have seen the stump of a tree which has been gnawed down by a beaver,” Roosevelt commented wryly, “will understand the exact force of the comparison.”101

![]()

THE COLD WORSENED as they started to erect the walls of the house. For two weeks temperatures hovered around minus 10 degrees Fahrenheit, plummeting at night to 50 degrees below zero.102 Trees cracked and jarred from the strain of the frost, and the wheels of the ranch wagon sang on the marble-hard ground. Roosevelt’s cattle huddled for warmth, with “saddles” of powdered snow lying across their backs and icicles hanging from their lips. He wondered that they did not die. At night the stars seemed to snap and glitter, coyotes howled with weird ventriloquial effects, and white owls hovered in the dark like snow-wreaths.103

Tactfully dissuaded from “helping” Sewall and Dow with construction, Roosevelt returned to Maltese Cross and tried to write the book he had been meditating upon all summer. But he was too cold, or too restless, to do more than a few thousand words.104 He read poetry, roamed the slippery slopes in pursuit of bighorn sheep, broke ponies, lunched at Château de Morès with the Marquis, and—ever the politician—campaigned up and down the valley to organize a Little Missouri Stockmen’s Association. On one such trip he managed to freeze his face, one foot, both knees, and one hand.105

Despite all this activity, there were periods of depression, stimulated by the bleakness of the weather, which seemed so symbolic of the bleakness in his own life. He sensed a relationship between the iron in his soul and the iron in the landscape. The texture of the frozen soil, its ringing sound-effects, the blue metallic sheen of the Little Missouri, are images which recur obsessively in his writings about Dakota, with constant repetitions of the word iron, iron, iron. All these elements synthesized in one magnificent prose-poem, entitled simply “Winter Weather.”

When the days have dwindled to their shortest, and the nights seem never-ending, then all the great northern plains are changed into an abode of iron desolation. Sometimes furious gales blow down from the north, driving before them the clouds of blinding snow-dust, wrapping the mantle of death round every unsheltered being that faces their unshackled anger. They roar in a thunderous bass as they sweep across the prairie or whirl through the naked canyons; they shiver the great brittle cottonwoods, and beneath their rough touch the icy limbs of the pines that cluster in the gorges sing like the chords of an æolian harp. Again, in the coldest midwinter weather, not a breath of wind may stir; and then the still, merciless, terrible cold that broods over the earth like the shadow of silent death seems even more dreadful in its gloomy rigor than is the lawless madness of the storms. All the land is like granite; the great rivers stand still in their beds, as if turned to frosted steel. In the long nights there is no sound to break the lifeless silence. Under the ceaseless, shifting play of the Northern Lights, or lighted only by the wintry brilliance of the stars, the snow-clad plains stretch out into dead and endless wastes of glimmering white.106

With the New Year, and spring, and the return of the meadowlark to Dakota, his blood would begin to run warm again.