Then said Olaf, laughing,

“Not ten yoke of oxen

Have the power to draw us

Like a woman’s hair!”

![]()

THE HA-HA-HONK, HA-HONK of wild geese grew louder in his ears. With unfocused eyes he watched the V-shaped skein flying low and heavily overhead and settling about a mile upriver. Then he hunched again over Bamie’s desk and scrawled, in his large, school-boyish hand, “I took the rifle instead of a shotgun and hurried after them on foot.”1

Roosevelt had learned, that January of 1885, the old truism that writers write best when removed from the scene they are describing. At Elkhorn and Maltese Cross, he had been too much a part of his environment to re-create it on paper. Fleeing the reality of Dakota just before Christmas, he began to write almost immediately after arriving in New York.2 During the first nine weeks of the New Year, nearly a hundred thousand words poured from his pen; by 8 March, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman was finished. “I have just sent my last roll of manuscript to the printer,” he told Cabot Lodge. While modest about the quality of his prose, Roosevelt declared that “the pictures will be excellent.”3 It is not known whether by this he meant the book’s illustrations, or a series of publicity photographs of himself, in the full glory of his buckskin suit.

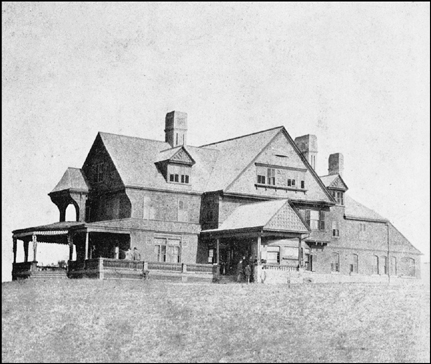

“Now for the first time he could admire his recently completed house.”

Sagamore Hill in 1885. (Illustration 12.1)

One of these was chosen as frontispiece, and caused much hilarity when Hunting Trips came out.4

Bristling with cartridges, a silver dagger in his belt, Roosevelt stands with Winchester at the ready, against a studio backdrop of flowers and ferns. His moccasins are firmly planted on a mat of artificial grass. For some reason his spectacles have been allowed to dangle: although his finger is on the trigger, one doubts if he could so much as hit the photographer, let alone a distant grizzly. His expression combines pugnacity, intelligence, and a certain adolescent vulnerability which touched Lodge, at least, very tenderly.5

![]()

HUNTING TRIPS WAS PUBLISHED by G. P. Putnam’s Sons early in July, and dedicated “to that keenest of Sportsmen and truest of Friends, my Brother Elliott Roosevelt.”6 The first edition, limited to five hundred copies, set new standards of lavishness in Americana. It was printed on quarto-size sheets of thick, creamy, hand-woven paper, with two-and-a-half-inch margins and sumptuous engravings. Bound in gray, gold-lettered canvas, it retailed at the then unheard-of price of $15, and quickly became a collector’s item.7

The book was well reviewed on both sides of the Atlantic (the British Spectator said it “could claim an honorable place on the same shelf as Waterton’s Wanderings and Walton’s Compleat Angler”), went through several editions, and was soon accepted as a standard textbook of big-game hunting in the United States.8 Roosevelt’s first published work had also achieved textbook status, yet few critics could have guessed, without comparing title pages, that the same man had written both. Where The Naval War of 1812had been scholarly, dry, crammed with sterile statistics, Hunting Trips was lyrical, lush, and cheerfully rambling.

It shows signs of being too hastily written. Anecdotes are repeated three times over, purplish tinges mar the otherwise crystal prose, thrilling chapters end in anticlimax. There are examples of Roosevelt’s perennial tendency to praise himself with faint damns. Some zoological details are inaccurate,9 betraying the fact that the author had, after all, lived only a few parts of one year in Dakota. He is at pains, however, to give the impression that he is a leathery pioneer of many years’ standing.10

Less than half the text is about hunting as such. Although Roosevelt tells, with tremendous pace and gusto, the story of all his major expeditions, some of the best pages are those in which he muses on the beauty of the Badlands, the simple pleasures of ranch life, the joy of being young and free on the frontier. Except for an occasional outpouring of melancholy adjectives, he gives no indication that he was a brokenhearted man during most of these adventures. On the contrary, there is an abundance of lusty, sensuous images: the carpet-like softness of prairie roses under his horse’s hooves, the smell of bear’s blood on his hands, the taste of jerked beef after a mouthful of snow, and—most memorably—the warm freshness of a deer’s bed, with its “blades of grass still slowly rising, after the hasty departure of the weight that has flattened them down.”11

Roosevelt’s characteristic auditory effects resonate on every page: from the “wild, not unmusical calls” of cowboys on night-herd duty, their voices “half-mellowed by the distance,” to the “harsh grating noise” of a dying elk’s teeth gnashing in agony. There are, to be sure, some vignettes that make non-hunters gag, such as that of a wounded blacktail buck galloping along “with a portion of his entrails sticking out … and frozen solid.”12 But the overwhelming impression left after reading Hunting Trips of a Ranchman is that of love for, and identity with, all living things. Roosevelt demonstrates an almost poetic ability to feel a bighorn’s delight in its sinewy nimbleness, the sluggish timidity of a rattlesnake, the cool air on an unsaddled horse’s back, the numb stiffness of a hail-bruised antelope.

How such a lover of animals could kill so many of them (at the time of writing his lifetime tally was already well into the thousands) is a perhaps unanswerable question.13 But his bloodthirstiness, if it can be called that, was not unusual among men of his classand generation. Roosevelt hunted according to a strict code of personal morality. He had nothing but contempt for “the swinish game-butchers who hunt for hides and not for sport or actual food, and who murder the gravid doe and the spotted fawn with as little hesitation as they would kill a buck of ten points. No one who is not himself a sportsman and lover of nature can realize the intense indignation with which a true hunter sees these butchers at their brutal work of slaughtering the game, in season and out, for the sake of the few dollars they are too lazy to earn in any other and more honest way.”14

![]()

ROOSEVELT’S ARDUOUS SPELL of writing in the early months of 1885 left him physically and emotionally drained. As usual when he was reduced to this condition, the cholera morbus struck, delaying his scheduled departure for Dakota from 22 March to 14 April. Even then he looked so pale and dyspeptic above his high white collar that Douglas Robinson wrote ahead to Bill Sewall, saying that his sisters were worried about him, and asking for reports of his health.15

If Sewall was conscientious enough to obey, he would have replied that Roosevelt seemed determined to contract pneumonia after arriving back in Medora. Although the weather was still wintry, the Little Missouri was swollen with dirty thaw-water from upcountry. The only way to cross it was to ride between the tracks of the railroad trestles—unless one chose, like Roosevelt, to negotiate the submerged, slippery top of a dam farther downstream. “If Manitou gets his feet on that dam, he’ll keep them there and we can make it finely,” he told Joe Ferris.

But halfway across Manitou overbalanced, and to the horror of spectators, horse and rider disappeared into the hurtling river. When they surfaced a few moments later, Roosevelt was seen swimming beside Manitou, pushing ice-blocks out of the horse’s way and splashing water in his face to guide him. They made the shore just in time to avoid being swept away completely: the next landing was more than a mile north.16

Roosevelt actually enjoyed the experience. A few days later he again swam across the river with Manitou, at a point where there were no spectators to rescue him. “I had to strike my own line for twenty miles over broken country before I reached home and could dry myself,” he boasted to Bamie. “However it all makes me feel very healthy and strong.”17

![]()

THE ELKHORN RANCH WAS NOW complete.18 Roosevelt, exploring its eight spacious rooms, found that they measured up in every way to the descriptions he had already written of them. Bearskins and buffalo robes strewed the beds and couches; a perpetual fire of cottonwood logs reddened the hearthstone; stuffed heads cast monstrous shadows across the rough log walls; there were rifles in every corner, coonskin coats and beaver caps hanging from the rafters. Sturdy shelves groaned with the collected works of Irving, Hawthorne, Cooper, and Lowell, as well as his favorite light reading—“dreamy Ike Marvel, Burroughs’s breezy pages, and the quaint, pathetic character-sketches of the Southern writers—Cable, Craddock, Macon, Joel Chandler Harris, and sweet Sherwood Bonner.” It was still too cold to sit out in his rocking-chair (“What true American does not enjoy a rocking-chair?”), but he looked forward to many summer afternoons on the piazza, reading or just simply contemplating the view. “When one is in the Bad Lands he feels as if they somehow look just exactly as Poe’s tales and poems sound.”19

He was pleased to see that his cattle had apparently survived the harsh winter well. “Bill, you were mistaken about those cows. Cows and calves are all looking fine.”

Nothing could shake Sewall’s habitual pessimism. “You wait until next spring, and see how they look.”20

Unfazed, Roosevelt sent Sewall and Dow to Minnesota, along with Sylvane Ferris, to help Merrifield bring back an extra fifteen hundred head. This latest purchase, amounting to $39,000, raised his total investment in the Badlands to $85,000, virtually half his patrimony. Coming on top of the $45,000 he had already spent at Leeholm, it made Roosevelt’s family as nervous about his finances as about his health. Bamie asked for guarantees that the cattle venture would pay, but got only the unconvincing reply, “I honestly think that it will.”21

![]()

THE NEW HERD ARRIVED in Medora on 5 May, and the bulk of it came north to Elkhorn under Roosevelt’s personal supervision. Never before had he attempted to manage so many cattle, and the experience nearly killed him. Since the river was still dangerously high, he was forced to stay clear of the valley, and trek inland. On the third day out the cattle had no water at all. That night they bedded down obediently, but an hour or two later, when Roosevelt and a cowboy were standing guard, a thousand thirst-maddened animals suddenly heaved to their feet and stampeded.

The only salvation was to keep them close together, as, if they once got scattered, we knew they could never be gathered; so I kept on one side, and the cowboy on the other, and never in my life did I ride so hard. In the darkness I could but dimly see the shadowy outlines of the herd, as with whip and spurs I ran the pony along its edge, turning back the beasts at one point barely in time to wheel and keep them in at another. The ground was cut up by numerous little gullies, and each of us got several falls, horses and riders turning complete somersaults. We were dripping with sweat, and our ponies quivering and trembling like quaking aspens, when, after more than an hour of the most violent exertion, we finally got the herd quieted again.22

![]()

PALE AND PATHETICALLY THIN, Theodore Roosevelt arrived at Box Elder Creek on 19 May to assist in the Badlands spring roundup. “You could have spanned his waist with your two thumbs and fingers,” a colleague remembered. The cowboys looked askance at his toothbrush and razor and scrupulously neat bed-roll.23 There were the usual jibes about his glasses, which he submitted to with resigned dignity. “When I went among strangers I always had to spend twenty-four hours in living down the fact that I wore spectacles, remaining as long as I could judiciously deaf to any side remarks about ‘four eyes,’ unless it became evident that my being quiet was misconstrued and that it was better to bring matters to a head at once.”24

He did not need to knock a man down during the next four weeks to win the respect of the cowboys—although there was one occasion when he told a Texan who addressed him as “Storm Windows” to “Put up or shut up.”25 It soon became apparent that Roosevelt could ride a hundred miles a day, stay up all night on watch, and be back at work after a hastily gulped, 3:00 A.M. breakfast. On one occasion he was in the saddle for nearly forty hours, wearing out five horses, and winding up in another stampede.26 He roped steers till his hands were flayed, wrestled calves in burning clouds of alkali-dust, and stuck “like a burr” to bucking ponies, while his nose poured blood and hat, guns, and spectacles flew in all directions.27 One particularly vicious horse fell over backward on him, cracking the point of his left shoulder. There was no doctor within a hundred miles, so he continued to work “as best I could, until the injury healed of itself.” It was weeks before he could raise his arm freely.28

“That four-eyed maverick,” remarked one veteran puncher, “has sand in his craw a-plenty.”29

![]()

THE ROUNDUP RANGED down the Little Missouri Valley for two hundred miles, fanning out east and west at least half as far again. During the five weeks that it lasted, sixty men riding three hundred horses coaxed some four thousand cattle out of the myriad creeks, coulees, basins, ravines and gorges of the Badlands, sorting them into proprietary herds and branding every calf with the mark of its mother. When Roosevelt withdrew from the action on 20 June, he had been with the roundup for thirty-two days, longer than most cowboys, and had ridden nearly a thousand miles.

“It is certainly a most healthy life,” he exulted. “How a man does sleep, and how he enjoys the coarse fare!”30

Some extraordinary physical and spiritual transformation occurred during this arduous period. It was as if his adolescent battle for health, and his more recent but equally intense battle against despair, were crowned with sudden victory. The anemic, high-pitched youth who had left New York only five weeks before was now able to return to it “rugged, bronzed, and in the prime of health,” to quote a newspaperman who met him en route. His manner, too, had changed. “There was very little of the whilom dude in his rough and easy costume, with a large handkerchief tied loosely about his neck … The slow, exasperating drawl and the unique accent that the New Yorker feels he must use when visiting a less blessed portion of civilization had disappeared, and in their place is a nervous, energetic manner of talking with the flat accent of the West.”31

In New York, another reporter was struck by his “sturdy walk and firm bearing.”32 Roosevelt’s own habitual assertion that he felt “as brown and tough as a hickory knot” at last carried conviction. All references to asthma and cholera morbus disappear from his correspondence. He was now, in the words of Bill Sewall, “as husky as almost any man I have ever seen who wasn’t dependent on his arms for his livelihood.”33

Throughout that summer Roosevelt continued to swell with muscle, health, and vigor. William Roscoe Thayer, who had not seen him for several years, was astonished “to find him with the neck of a Titan and with broad shoulders and stalwart chest.” Thayer prophesied that this magnificent specimen of manhood would have to spend the rest of his life struggling to reconcile the conflicting demands of a powerful mind and an equally powerful body.34

![]()

SUMMER WAS but five days old, and the sea breeze blew cool as Roosevelt’s carriage circled Oyster Bay and began to ascend the green slopes of Leeholm. Now, for the first time, he could admire his recently completed house. Huge, angular, and squat, it sat on the grassy hilltop with all the grace of a fort. Bamie’s gardeners had planted vines, shrubs, and saplings in an effort to refine its silhouette, but years would pass before leaves mercifully screened most of the house from view.35

As Roosevelt drew nearer, its newness and rawness became more apparent. The mustard-colored shingles had not yet mellowed, and the green trim clashed with florid brick and garish displays of stained glass. However, flowers were clustering around the piazza, last year’s lawns had come up thick and velvety, and spring rains had washed away the last traces of construction dirt.36 Roosevelt might be excused a surge of proprietary emotion.

Looking south across the bay toward Tranquillity (rented to others now, but still a symbol, in its antebellum graciousness, of Mittie), he could see the beach where “dem web-footed Roosevelts” used to run down to bathe; the private, reedy channels where he rowed little Edie Carow; the tidal waters where he and Elliott had once joyously battled a snowy northeaster and there, snaking west to the station, was the lane along which Theodore Senior used to speed, his linen duster ballooning out behind him. At nearer points, through the trees, could be seen the summerhouses of cousins and uncles and aunts. If there were some hillside walks, and a tennis court or two, that Roosevelt could not contemplate without being painfully reminded of his honeymoon, he had at last developed the strength to deal with allusive memories.37

In token of that strength, he decided that the name Leeholm must be changed. Henceforth his house would commemorate the Indian sagamore, or chieftain, who had held councils of war here two and a half centuries before.38 He would call it Sagamore Hill.

![]()

ROOSEVELT ALLOWED HIMSELF eight idyllic weeks in the East during the summer of 1885—his first period of relaxation in two years. Fanny Smith, now married to a Commander Dana and recovering from a miscarriage, was one of the many guests he invited to stay at Sagamore Hill. Although unable to take part in a frenetic schedule of outdoor activities, such as portaging across mosquito-infested mud flats and tumbling down Cooper’s Bluff into the sea, she was able to enjoy the stimulating conversation at Bamie’s dinner table. “Especially memorable were the battles, ancient and modern, which were waged relentlessly on the white linen tablecloth with the aid of such table-silver as was available.” Theodore’s penchant for military history made her feel “that Hannibal lived just around the corner.”

The entire household went into New York on 8 August to watch General Grant’s funeral parade. Roosevelt himself marched, in his capacity as a captain in the National Guard. “I shall never forget the tense expression on his face as he passed with his regiment,” wrote Fanny, “and it seemed to me that the bit of crêpe that floated from his rifle was conspicuous for its size.”39

Back at Sagamore Hill, Roosevelt indulged in many romps with little Alice, who was now a mass of yellow curls and just learning to walk. Occasionally, perhaps, he strolled through the trees to Grace-wood, where Aunt Annie lived, to cuddle little Eleanor Roosevelt, his brother’s ten-month-old daughter.40 On returning home, he could ponder the family motto carved in gold over the wide west door: Qui plantavit curabit—he who has planted will preserve.

Roots were forming—fragile ones, exploratory as those of his saplings, yet sure to anchor him permanently someday. Right now his other roots out West seemed lustier and stronger. He was bound to return to his ranch, and would, in time, inhabit many houses, including the grandest in the land; but sooner or later these roots would cause all others to wither, and he would come back more and more to Sagamore Hill. Here hung the hallowed portrait of his father, and various stuffed symbols of his own manhood—the buffalo, the bears, the many antelope heads. The place was loud with the happy squeals of his daughter, the conversation of his friends and relatives. This endearingly ugly house was Home. In it he would live out his sixty years (Roosevelt was already quite sure of that figure)41 and die.

But for the time being, he was twenty-six, and the Wild West was calling. Urging Bamie to continue her entertainments on his behalf, he caught the Chicago Limited out of New York on 22 August 1885.42

![]()

NEWSPAPERMEN WERE WAITING to interview Roosevelt at St. Paul and Bismarck as usual, but for some reason they seemed more interested in talking about the Marquis de Morès than about politics. Was it true that he and the Marquis had recently had “a slight tilt,” and that their relations were “somewhat strained”?43

The only “tilt” Roosevelt could think of—and it was trivial, in his opinion—was a business misunderstanding that had occurred during the spring. He had contracted to sell some cattle to the Northern Pacific Refrigerator Car Company at a price of six cents a pound, but on delivery de Morès had reduced the price to five and a half cents a pound, saying that the market in Chicago was down by that much. Roosevelt, in turn, had insisted that a contract was a contract, irrespective of price fluctuations afterward; but the Marquis remained obdurate. Roosevelt had philosophically taken his cattle back, and let it be known that he would not do business with the Marquis again.44

Now, months later, he sought to play down the incident. It was “not true,” he said, that the two cattle kings of the Badlands were “looking for each other with clubs.” The story of a “tilt” was exaggerated; but why all these questions? He found out soon enough. The Marquis de Morès had just been indicted for murder.45

Roosevelt reached Medora on 25 August, and paused only to announce a meeting of his Little Missouri Stockmen’s Association on 5 September before hurrying north to discuss the indictment with Sewall and Dow.46 He already knew the facts. This “murder” was nothing new—merely another skirmish in the legal war that had been waged against de Morès ever since the fatal ambush of 26 June 1883. Charges that the Marquis had killed Riley Luffsey had twice been examined by justices of the peace, and twice dismissed for lack of proof; yet now a grand jury in Mandan had decided there was enough evidence to warrant a trial.47

De Morès, who had also been vacationing in the East, arrived in Dakota close on Roosevelt’s heels, and gave himself up to the authorities. They told him that “a little matter of fifteen hundred dollars judiciously distributed” would cause the indictment to be withdrawn. “I have plenty of money for defense,” he replied haughtily, “but not a dollar for blackmail.” He was promptly placed in Bismarck jail.48

![]()

A SUBTLY TRANSFORMED ranch house greeted the returning proprietor of Elkhorn. There were unmistakable signs of feminine occupation: patches of bright color in the windows, delicate items of laundry hanging up to dry, a new air of neatness and tidiness. Inside,Roosevelt found Mrs. Sewall and Mrs. Dow, along with Kitty Sewall, “a forlorn little morsel” about the same age as Baby Lee. Dow had brought them all West three weeks before.49

Roosevelt was pleased to have more company under his roof. The ranch house was amply big enough for six—so big, indeed, that it needed domestic management. The women, in turn, were anxious to repay him for their free board and lodging. They swept and scrubbed and polished, mended his linen, and at regular intervals sorted out his possessions so he could find what he was looking for.50 Best of all, they fed him—not as elaborately as Bamie on the polished boards of Sagamore Hill, but from the nutritional point of view probably better. After a dusty morning’s work on the range or in the corral he would return ravenous to the Elkhorn table, “on the clean cloth of which are spread platters of smoked elk meat, loaves of good bread, jugs and bowls of milk, saddles of venison or broiled antelope-steaks, perhaps roast and fried prairie chickens with eggs, butter, wild plums, and tea or coffee.”51 Sometimes there were potatoes coaxed from the harsh alkaline soil, jars of buffalo-berry jam, dishes of jelly and cake. Roosevelt’s appetite had grown prodigious since his physical transformation in the spring, and he gobbled everything greedily. No doubt he continued to put on weight, but the hard exercise of ranch life kept him, in Bill Sewall’s words, “clear bone, muscle, and grit.”52

![]()

GRIT OF ANOTHER SORT was called for on 5 September, when Roosevelt, who had gone to Medora to chair the Stockmen’s Association meeting, received the following letter from a jail cell in Bismarck:

My dear Roosevelt My principle is to take the bull by the horns. Joe Ferris is very active against me and has been instrumental in getting me indicted by furnishing money to witnesses and hunting them up. The papers also published very stupid accounts of our quarreling … Is this done by your order? I thought you my friend. If you are my enemy I want to know it. I am always on hand as you know, and between gentlemen it is easy to settle matters of that sort directly.

Yours very truly

MORÈS

Sept. 3, 188553

Roosevelt’s first reaction must have been bewilderment. Despite their little skirmishes over beef prices and grazing rights, he and the Marquis got on fairly well. They had entertained each other at lunch, exchanged books and newspapers, and there had even been an occasion, during a square dance in honor of the spring roundup, when they solemnly took the floor together, and “do-si-do’d” with cowgirls.54 Yet there was no mistaking the threatening tone of this letter. He could not have read it without a pang of real fear. The Marquis was known to have killed at least two men in duels, and his feats of marksmanship, such as picking off prairie chickens on the wing with a 20–30 Winchester, were legendary.55 If his letter was, as it seemed, a challenge to arms, Roosevelt would have the choice of weapons; but that was of small comfort to a myopic individual who claimed to be “not more than an ordinary shot.”56 The Marquis’s trial was already under way, and if acquitted he might demand satisfaction at once.

Before replying it was necessary to clarify the Frenchman’s cloudy umbrage. He obviously believed that Joe Ferris, Roosevelt’s old buffalo guide, was bribing witnesses, and with Roosevelt’s money. Joe was now a storekeeper in Medora, but he also acted as the unofficial banker of the Badlands. Cowboys would deposit their earnings with him for safekeeping, and withdraw cash from time to time—when they had to go to Bismarck to testify at a murder trial, for instance.57 The Marquis must be unaware of this. All he didknow was that Roosevelt had financed Joe’s store,58 and therefore suspected that the same person might well be financing his prosecution.

De Morès also complained about articles publicizing the so-called “tilt.” These rumors had been put out by reporters who regularly interviewed Roosevelt at railroad stations farther east: conceivably he could have leaked the stories on his latest trip to New York, knowing that by the time he returned to deny them they would be accepted as fact.

The last and most damaging proof of ill will, as far as de Morès was concerned, was that one of the men to receive money from Joe Ferris before the trial was Dutch Wannegan, a victim of the original ambush, a key prosecution witness, and—for the past year or more—an employee of Theodore Roosevelt.59

All these misconceptions might surely be explained away, but how could de Morès ever have imagined that the most decent man in the Badlands was plotting his destruction? Roosevelt, staring dumbfounded at the letter in his hand, knew the notion was preposterous. He discussed his options with Sewall, and said that he was opposed to dueling on principle. But he could not ignore such a challenge; he must answer de Morès in kind. “I won’t be bullied by a Frenchman … What do you say if I make it rifles?”60Sitting down on a log, and flipping the letter over, he scrawled on its back the draft of his reply:

MEDORA, DAKOTA,

September 6, 1885

Most emphatically I am not your enemy; if I were you would know it, for I would be an open one, and would not have asked you to my house nor gone to yours. As your final words, however, seem to imply a threat, it is due to myself to say that the statement is not made through any fear of possible consequences to me; I too, as you know, am always on hand, and ever ready to hold myself accountable in any way for anything I have said or done. Yours very truly

THEODORE ROOSEVELT61

Sewall agreed to act as second, while doubting that the duel would ever take place. “He’ll find some way out of it.”62

A few days later a courier arrived with another message from the Marquis. Roosevelt showed it to Sewall. “You were right, Bill.” De Morès protested that he had implied no threat in his previous letter. He meant, simply, that “there was always a way to settle misunderstandings between gentlemen—without trouble.” The tone of this letter was sufficiently conciliatory for Roosevelt to boast later that the Marquis had “apologized.”63

And so the epic confrontation fizzled out—disappointingly, for those like E. G. Paddock, who had hoped for violence, but decisively in Roosevelt’s favor nonetheless. From then on, progress toward organization was rapid in Billings County. Newspapers began to speak of Roosevelt as the likely first Senator from Dakota, when the territory was elevated to statehood.64

![]()

AUTUMN CAME EARLY to the Badlands, but the cooling air did not prevent the sun from burning every last drop of green juice out of the grass. The prairie became a brittle carpet underfoot, wanting only the spark of a horseshoe on stone—or a tumbling ember of lignite—to erupt into flame.65 Several times that September, Roosevelt found himself fighting fires on his own range.66 Similar fires were reported all over Billings County. Stockmen plotted their various locations and grew increasingly suspicious. All the outbreaks were in the “drive” country—a broad strip of grassland lying between the Northern Pacific Railroad and the cattle ranches on either side. This strip, fifty miles wide and hundreds of miles long, had to be crossed by any herd en route to shipping points like Mingusville and Medora. Cattle driven over the blackened wastes shed tons of weight; on delivery they could be sold only as low-grade beef. Clearly it was not nature that so shrewdly sabotaged the profits of stockmen. The fires were being set by Indians, in protest against being deprived of their ancient hunting grounds in the Badlands.67

Roosevelt’s attitude toward the red man in 1885 was no more tolerant than that of any cowboy. He had publicly explained it in Hunting Trips of a Ranchman:

During the past century a good deal of sentimental nonsense has been talked about our taking the Indians’ land. Now, I do not mean to say for a moment that gross wrong has not been done the Indians, both by government and individuals, again and again … where brutal and reckless frontiersmen are brought into contact with a set of treacherous, vengeful, and fiendishly cruel savages a long series of outrages by both sides is sure to follow. But as regards taking the land, at least from the Western Indians, the simple truth is that the latter never had any real ownership in it at all. Where the game was plenty, there they hunted; they followed it when they moved away to new hunting grounds, unless they were prevented by stronger rivals, and to most of the land on which we found them they had no stronger claim than that of having a few years previously butchered the original occupants. When my cattle came to the Little Missouri, the region was only inhabited by a score or so white hunters; their title to it was quite as good as that of most Indian tribes to the lands they claimed; yet nobody dreamed of saying that these hunters owned the country … The Indians should be treated in just such a way that we treat the white settlers. Give each his little claim; if, as would generally happen, he declined this, why, then let him share the fate of the thousands of white hunters and trappers who have lived on the game that the settlement of the country has exterminated, and let him, like these whites, perish from the face of the earth which he cumbers.68

One day in early fall Roosevelt set off on another of his solo rides across the prairie.69 This time he headed northeast. He knew that he was wandering into “debatable territory,” where white land bordered on red, and knew of at least one cowboy who had been killed hereabouts by a band of marauding bucks; but this, of course, was more likely to challenge him than deter him. He was crossing a remote plateau when, suddenly, five Indians rode up over the rim.

The instant they saw me they whipped out their guns and raced full speed at me, yelling and flogging their horses. I was on a favorite horse, Manitou, who was a wise old fellow, with nerves not to be shaken at anything. I at once leaped off him and stood with my rifle ready.

It was possible that the Indians were merely making a bluff and intended no mischief. But I did not like their actions, and I thought it likely that if I allowed them to get hold of me they would at least take my horse and rifle, and possibly kill me. So I waited until they were a hundred yards off and then drew a bead on the first. Indians—and for the matter of that, white men—do not like to ride in on a man who is cool and means shooting, and in a twinkling every man was lying over the side of his horse, and all five had turned and were galloping backwards, having altered their course as quickly as so many teal ducks.

After this one of them made the peace sign, with his blanket first, and then, as he rode toward me, with his open hand. I halted him at a fair distance and asked him what he wanted. He exclaimed, “How! Me good Injun, me good Injun,” and tried to show me the dirty piece of paper on which his agency pass was written. I told him with sincerity that I was glad that he was a good Indian, but that he must not come any closer. He then asked for sugar and tobacco. I told him I had none. Another Indian began slowly drifting toward me in spite of my calling out to keep back, so I once more aimed with my rifle, whereupon both Indians slipped to the side of their horses and galloped off, with oaths that did credit to at least one side of their acquaintance with English.70

Although Roosevelt later dimissed this as “a trifling encounter,” it is further, perhaps unnecessary proof of his extraordinary courage.71

![]()

MEANWHILE, THE MURDER TRIAL of the Marquis de Morès was making daily headlines in the Dakota newspapers. Proceedings dragged on for week after week, but little fresh evidence was forthcoming. Neither prosecution nor defense could establish who fired first when the trio of frontiersmen rode into the Marquis’s ambush, and whose bullet had killed Riley Luffsey. The Marquis was his own best witness. Tall, calm, and dignified, he spoke in simple sentences that made the testimony of Dutch Wannegan sound maundering and untruthful.72

On 16 September Roosevelt passed through Bismarck—en route to the New York State Republican Convention—and briefly visited the Marquis in his jail cell. De Morès sat tranquilly smoking, confident of a favorable verdict. Continuing on to New York, Roosevelt arrived just in time to read the news that the Frenchman had been acquitted.73

![]()

NOT MUCH NEEDS to be said of Roosevelt’s routine activities at the Convention in Saratoga, except that he helped draft the party platform and campaigned unsuccessfully on behalf of a reform candidate for the gubernatorial nomination.74 Little notice was taken of him during the ensuing county and state campaigns, which ended in general victory for the Democrats. The impression is that he worked with his usual energy and devotion to the reform cause, but without his usual flamboyance.75 For once he did not need “the full light of the press beating upon him.” There was radiance enough in his private life, the radiance of such happiness as he had not known in almost two years. Its secret source lay neither in politics, nor in the adulation of his family and friends, nor in his own superabundant health and vigor. He was in love.

![]()

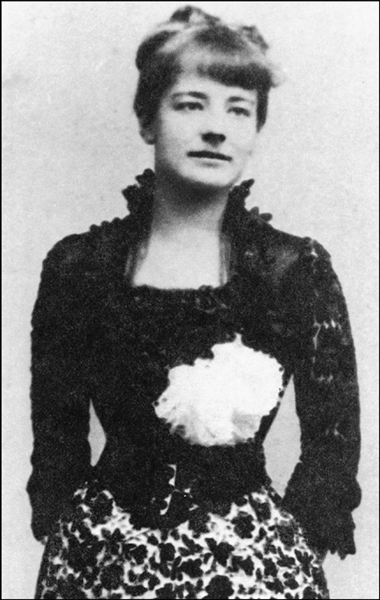

ONE DAY THAT FALL—probably in early October, although the exact date is unknown—Roosevelt returned to his pied-à-terre at 422 Madison Avenue and, opening the front door, met Edith Carow coming down the stairs. For twenty months now, since the death of Alice Lee, he had successfully managed to avoid her. It had been impossible, however, to avoid hearing items of news about his childhood sweetheart, who was still Corinne’s closest friend and a regular visitor to Bamie’s house on days when he was not in town. He must have known of the rapid decline in the Carow family fortunes, following the death of her improvident father in 1883; of the decision by her mother and younger sister to live in Europe, where their eroded wealth might better support them; of Edith’s decision to go with them, having considered, and dismissed, the idea of marrying for money; of her curious aloofness, cloaked behind great sweetness of manner, which frustrated many a would-be beau; of evidence that poor “Edie,” at twenty-four, was already an old maid.76But that latter item, at least, was mere negative rumor, whereas here, confronting him (had Bamie plotted this deliberately?), was positive reality. Edith was as alarmingly attractive as he had feared—even more so, perhaps, for she had matured into complex and exciting womanhood. He could not resist her.

Nor could Edith resist him. The Theodore she saw was unrecognizably different from the Teedie she knew as a child, or the Teddy of more recent years. He was a mahogany-brown stranger, slim of leg and forearm, inclining to burliness about the head and shoulders. Most changed of all was the bull-like neck, heavy with muscle and bulging out of his city collar as if about to pop its studs. His hair was sun-bleached, and cropped shorter than she had ever seen it, making his massive head look even larger. Only the reddish-brown mustache had been allowed to sprout freely and droop at the corners in approved cowboy fashion. His toothy smile was the same, and the eyes behind the flashing spectacles were still big and childishly blue. But the corrugations of his mobile face had multiplied and were much more deeply etched than she could remember. Edith had to accept the fact that his boyish ingenuousness, which used to be one of his great charms, was gone. In its place were reassuring signs of wisdom and authority.

Theodore, for his part, saw a woman of slender yet appealingly rounded figure, with small hands and feet which assumed semiballetic poses when she hesitated, as then, on a stair, in the knowledge that she was being examined. Whether the scrutiny was friendly or hostile, Edith flinched against it; her privacy was so intense, her sensitiveness so extreme, that she stiffened as if posing for an unwelcome photograph. Her own gaze—when she chose to direct it (for the wide-spaced eyes were usually set at an oblique angle)—was icy blue and uncomfortably penetrating. Its strength belied the general air of softness and shyness, and flashed the unmistakable warning, hurt me and I will hurt you more. Her jaw was firm, and her mouth was wide, tightly controlled at the corners. Smiles did not come easily. Yet they did come on occasion, and they transformed her amazingly, for her teeth were pretty, and her cheekbones elegant beneath the peach-like skin. Her most arresting feature, best seen in profile, was a long, sharp, yet classically beautiful nose, of the kind that Renaissance portraitists loved to draw in silverpoint. Here was a person of refinement and steely discipline, yet in the glow of her flesh there was a hint of earthiness, and much sexual potential.77

No details are known about the meeting in the hallway, except that it occurred,78 and that it was, inevitably, followed by others. Whether these encounters were few or many—again the record is blank—they were certainly ardent, for on 17 November Theodore proposed marriage, and Edith accepted him.79

![]()

THE ENGAGEMENT WAS KEPT a secret, even from their closest relatives. Should the merest whisper of it break out, polite society, just then convening for the season, would be scandalized. Roosevelt, after all, had been only twenty-one months a widower. To post, with such indecent haste, from the arms of Alice Lee to those of Edith Carow—having done the reverse seven years before—was hardly the conduct of a gentleman, let alone a politician famous for public moralizing. At all costs it must seem that Theodore and Edith had merely resumed an old family friendship. Announcement of the engagement must be put off for a year at least.80 In the meantime they could privately, carefully, adjust to the violent change which had taken place in their lives.

![]()

LOVE AND POLITICS were not enough to drain Roosevelt’s well of vitality in the fall of 1885. If anything, they intensified its flow. During his free time at Sagamore Hill he threw himself into a new sport, as strenuous and bloodthirsty as any of his Western activities, albeit more elegant: hunting to hounds. He had experimented with it a few times before, but rather disdainfully, for the pursuit of the fox was at that time considered effete and un-American.81 But now, with the encouragement of Henry Cabot Lodge, an enthusiastic huntsman, he suddenly discovered in it the “stern and manly qualities” that had to justify all his amusements. Long Island’s Meadow-brook Hunt was certainly one of the toughest in the world: the Marquis de Morès told Roosevelt that he had never seen such stiff jumping.82

Having formally adopted the pink coat, Roosevelt wore it as proudly as his buckskin tunic, and galloped after fox with the same energy he once devoted to buffalo. Often he was “in at the death” ahead of the huntmaster.83 Although the technique of riding wooded Long Island country was totally different from that he had acquired out West, he showed no fear of coming a serious cropper.

On Saturday morning, 26 October, the hunt met at Sagamore Hill, and after the traditional stirrup cup set off over particularly rough country. High timber obstacles of five feet or more followed one upon another at a frequency of six to the mile. Some of these barriers were post-and-rail fences, as stiff as steel and deadly dangerous: even Filemaker, America’s best jumper, began to hang back nervously.84

Roosevelt, riding a large, coarse stallion, led from the start. Careless of accidents which dislocated the huntmaster’s knee, smashed another rider’s ribs, and took half the skin off his brother-in-law’s face,85 he galloped in front for fully three miles. Eventually his exhausted horse began to go lame; at about the five-mile mark it tripped over a wall and pitched over into a pile of stones. Roosevelt’s face smashed against something sharp, and his left arm, only recently knit after the roundup fracture, snapped beneath the elbow. Yet he was back in the saddle as soon as the horse was up, and rushed on one-armed, determined not to miss the death. After five or six further jumps the bones of his broken arm slipped past one other, and it dangled beside him like a length of liverwurst; but this, and the blood pouring down his face, did not deter him from pounding across fifteen more fields. He had the satisfaction of finishing the hunt within a hundred yards of the other riders, and returned to Sagamore Hill looking “pretty gay … like the walls of a slaughter-house.”86 Baby Lee, who was waiting at the stable for him, ran away screaming from the bloody monster, and he pursued her, chortling.87

Washed clean that night, his cut face plastered and his arm in splints, he presided over the Hunt Ball as laird of Sagamore. Edith Carow was his guest,88 and took her first cool survey of her future home. At midnight, Theodore Roosevelt turned twenty-seven. With his daughter asleep upstairs, his house full of music and laughter, and Edith at his side, he could abandon himself to bliss rendered piquant by pain. Later he wrote to Lodge: “I don’t grudge the broken arm a bit … I’m always ready to pay the piper when I’ve had a good dance; and every now and then I like to drink the wine of life with brandy in it.”89

“Here was a person of refinement … and much sexual potential.”

Edith Kermit Carow at twenty-four. (Illustration 12.2)